i. the text of light

The filmmaker Stan Brakhage is one of those people whose work hangs in the back of my mind with a frequency well out of proportion to my actually engaging with his work. I first (and really, only, until recently) saw his films about seven years ago, when he introduced a marathon screening of what must have been almost his complete works. Hours later, I stumbled out of the theatre, knowing that this was someone whose work I should have seen years before, having seen on the screen something new to me, a new way of looking at the possibility of film. I’ve felt an analogous sensation with only a handful of artists and writers; I’ve found it again in the luminously fractured English of Amos Tutuola, Ray Johnson’s conceptual games of “correspondance”, and Michel Butor’s reimagining of the page and narrative.

The filmmaker Stan Brakhage is one of those people whose work hangs in the back of my mind with a frequency well out of proportion to my actually engaging with his work. I first (and really, only, until recently) saw his films about seven years ago, when he introduced a marathon screening of what must have been almost his complete works. Hours later, I stumbled out of the theatre, knowing that this was someone whose work I should have seen years before, having seen on the screen something new to me, a new way of looking at the possibility of film. I’ve felt an analogous sensation with only a handful of artists and writers; I’ve found it again in the luminously fractured English of Amos Tutuola, Ray Johnson’s conceptual games of “correspondance”, and Michel Butor’s reimagining of the page and narrative.

But Brakhage. His films tend to be short and silent. His editing, if it can be called such, is quick – often an image only shows for a frame, then it’s gone. In most of his films, he cuts quickly between shots; in some of his work he abandoned the camera entirely to work directly with the film stock itself, painting on it or gluing things to it. Jean-Luc Godard said that the cinema was the truth twenty-four times a second; rarely has this been so literally explicated as in Brakhage’s films. Mitchell Stephens, in The Rise of the Image, the Fall of the Word saw in the lighting-fast editing style that Brakhage introduced a possible future for communication. But Brakhage was following his own very particular muse. His aim, he declared in one of his later films, was to show on film what the eye sees when it is closed, the phenomenon of dancing spots of color that’s been termed hypnogogic vision.

But Brakhage. His films tend to be short and silent. His editing, if it can be called such, is quick – often an image only shows for a frame, then it’s gone. In most of his films, he cuts quickly between shots; in some of his work he abandoned the camera entirely to work directly with the film stock itself, painting on it or gluing things to it. Jean-Luc Godard said that the cinema was the truth twenty-four times a second; rarely has this been so literally explicated as in Brakhage’s films. Mitchell Stephens, in The Rise of the Image, the Fall of the Word saw in the lighting-fast editing style that Brakhage introduced a possible future for communication. But Brakhage was following his own very particular muse. His aim, he declared in one of his later films, was to show on film what the eye sees when it is closed, the phenomenon of dancing spots of color that’s been termed hypnogogic vision.

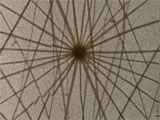

Mothlight, stills from which can be seen floating about this post, was one of the films that stuck most clearly in my mind. In it, Brakhage set out to show “what a moth might see from birth to death if black were white and white were black.” The ratio of the size of the moth to that of ourselves is roughly that of the size of a film negative to the blown up film; with this in mind, and a collection of dead moths that had flown into a light and perished, Brakhage composed a three-minute film, every frame of which is composed of things from the moth’s world: wings, plant leaves, and flowers. Brakhage pasted these objects directly onto the film stock. When the film is projected there’s a rush of images made unfamiliar by size: a moth wing or a flower twenty feet wide is something we’ve never seen before. Though constructed of objects that we imagine we know, the moth’s world as Brakhage depicts it is utterly foreign to us. Speed has a lot to do with it: the eye can’t possibly process twenty-four different images per second. The moth’s world is much faster than our own.

Mothlight, stills from which can be seen floating about this post, was one of the films that stuck most clearly in my mind. In it, Brakhage set out to show “what a moth might see from birth to death if black were white and white were black.” The ratio of the size of the moth to that of ourselves is roughly that of the size of a film negative to the blown up film; with this in mind, and a collection of dead moths that had flown into a light and perished, Brakhage composed a three-minute film, every frame of which is composed of things from the moth’s world: wings, plant leaves, and flowers. Brakhage pasted these objects directly onto the film stock. When the film is projected there’s a rush of images made unfamiliar by size: a moth wing or a flower twenty feet wide is something we’ve never seen before. Though constructed of objects that we imagine we know, the moth’s world as Brakhage depicts it is utterly foreign to us. Speed has a lot to do with it: the eye can’t possibly process twenty-four different images per second. The moth’s world is much faster than our own.

The memory of that flicker of images has stayed with me, as much for its ephemerality as anything else: I’d seen something briefly, not long enough to remember the images themselves, but long enough to remember the film more clearly than nearly anything else I saw that year.

ii. the act of seeing with one’s own eyes

The Criterion Collection released a two-DVD set of some of Brakhage’s films a few years ago, a year or so before he passed away and was briefly in the news again. I’m not sure why I held off buying a copy of the DVD: maybe a devotion to the ephemerality of memory? I did convince an old roommate, a painter, to buy his own copy soon after it was released: independently, he had been trying to capture with oils hypnogogic visions of his own. But I didn’t get a copy until a few weeks ago, when after finding him again in Mitchell Stephens’s book, I broke down for an online Christmas DVD sale. It arrived, and I inserted one of the discs into my Powerbook, curious to see how his films compared to my memory of them.

The Criterion Collection released a two-DVD set of some of Brakhage’s films a few years ago, a year or so before he passed away and was briefly in the news again. I’m not sure why I held off buying a copy of the DVD: maybe a devotion to the ephemerality of memory? I did convince an old roommate, a painter, to buy his own copy soon after it was released: independently, he had been trying to capture with oils hypnogogic visions of his own. But I didn’t get a copy until a few weeks ago, when after finding him again in Mitchell Stephens’s book, I broke down for an online Christmas DVD sale. It arrived, and I inserted one of the discs into my Powerbook, curious to see how his films compared to my memory of them.

Watching him the first time, I’d been supine before the screen. Watching him on my laptop was something different, something surprising. My first impulse after starting one of the films playing was the obvious one when something’s going too fast, but not an option that one has when you’re part of an audience: to hit the pause button. The moth wings, spider webs, flowers, and blades of grass instantly snap into startling focus: around every object, you can see the halo of glue that Brakhage used to hold it to the celluloid. Then another pleasant surprise: on the Apple DVD player, if you then press the right arrow button, you can advance one frame. Not another frame in the same shot, as one would expect in an ordinary film, but another image entirely, though sometimes, you realize, a connected object: in some frames one sees the top of a plant leaf, in the following, the bottom, exactly as Brakhage constructed the film. (Images of the film stock itself – not just screencaptures from the DVD – can be seen at critic Fred Camper’s website, which offers a dizzying amount of information on Stan Brakhage.)

Watching him the first time, I’d been supine before the screen. Watching him on my laptop was something different, something surprising. My first impulse after starting one of the films playing was the obvious one when something’s going too fast, but not an option that one has when you’re part of an audience: to hit the pause button. The moth wings, spider webs, flowers, and blades of grass instantly snap into startling focus: around every object, you can see the halo of glue that Brakhage used to hold it to the celluloid. Then another pleasant surprise: on the Apple DVD player, if you then press the right arrow button, you can advance one frame. Not another frame in the same shot, as one would expect in an ordinary film, but another image entirely, though sometimes, you realize, a connected object: in some frames one sees the top of a plant leaf, in the following, the bottom, exactly as Brakhage constructed the film. (Images of the film stock itself – not just screencaptures from the DVD – can be seen at critic Fred Camper’s website, which offers a dizzying amount of information on Stan Brakhage.)

Technically, this is not very exciting at all: pausing to see a crisp frame is just one of the niceties of the DVD that we’re all used to. But what this does to the viewer’s experience of the film is immeasurable. Instead of the imposed stricture of watching the images projected at 24 frames per second, you’re free to proceed through Brakhage’s frames at any rate you like – his film becomes something like a slide show. As great a change, though, is imparted to the viewer, who goes from being a passive recipient of speeding images to an active participant with control over what’s being shown.

This isn’t, it’s worth pausing to consider, something that would have been possible with a VHS tape. Video didn’t respect the frames of film, and a paused VHS tape generally gives you a blurred and indistinct image. Presumably with a projector and a copy of the original films, you could do the same thing. (This would also resolve the incongruity of looking at images that are meant to have light projected through them rather than being composed of red, green, and blue blips of it, as on my computer screen.) Alas, not many of us have our own movie theater to try this out in. For the rest of us, this amount of control is something that arrives with new digital media, and deserves to be considered as a function of it.

This isn’t, it’s worth pausing to consider, something that would have been possible with a VHS tape. Video didn’t respect the frames of film, and a paused VHS tape generally gives you a blurred and indistinct image. Presumably with a projector and a copy of the original films, you could do the same thing. (This would also resolve the incongruity of looking at images that are meant to have light projected through them rather than being composed of red, green, and blue blips of it, as on my computer screen.) Alas, not many of us have our own movie theater to try this out in. For the rest of us, this amount of control is something that arrives with new digital media, and deserves to be considered as a function of it.

From time to time, Bob talks to the programmers busy making Sophie about imagining film as being a book that’s flipping through 86,400 pages per hour. This sort of talk tends to throw them into conniptions (to paraphrase: nobody in their right mind thinks that way & how current processors don’t have nearly enough computational power and they probably won’t for the next fifty years). But despite their objections, that’s almost exactly what we have here, if not through design. It’s worth noting, of course, that the tools for reading film in this way aren’t yet perfect: while I can press the right arrow to advance a frame in my DVD player, I can’t, for some reason, press the left arrow to go back a frame: you have to rewind. I can’t look at several consecutive frames together without a fair amount of work. There’s more work for the programmers.

iii. mothlight

Thinking about technology for the past month or so, I’ve often found myself in a mild funk, which might be the sort of thing one expects to set in around the end of the year, when I, at least, find myself wanting to neatly box the disjointed events of the past year to take up to the attic for storage. The crux of my worrying: while there’s clearly no shortage for ideas of new ways to say things – as even a cursory reading of this blog will readily attest – there seems to be a comparative paucity of new ways to understand things. Maybe this makes sense: people like novelty. It’s more exciting to announce something brand new and different than to find a new way to look at something familiar. Who can be bothered to care about a fourteenth way of looking at a blackbird when you can make your own genetically-modified fuchsia- and chartreuse-birds?

Thinking about technology for the past month or so, I’ve often found myself in a mild funk, which might be the sort of thing one expects to set in around the end of the year, when I, at least, find myself wanting to neatly box the disjointed events of the past year to take up to the attic for storage. The crux of my worrying: while there’s clearly no shortage for ideas of new ways to say things – as even a cursory reading of this blog will readily attest – there seems to be a comparative paucity of new ways to understand things. Maybe this makes sense: people like novelty. It’s more exciting to announce something brand new and different than to find a new way to look at something familiar. Who can be bothered to care about a fourteenth way of looking at a blackbird when you can make your own genetically-modified fuchsia- and chartreuse-birds?

My funk wasn’t straight misoneism: I’m all for new forms else I wouldn’t be working here. But if we’re to create new forms that resonate as strongly as the physical book has been able to historically – a project that I suspect Brakhage considered himself engaged in – it’s just as important to find new ways to understand how what we’ve created works. And this is I think why the simple gesture of hitting the “pause” button in the middle of a film feels like something of a revelation to me, puncturing my December miasma. It’s not a blinding Damascene conversion, and that’s perhaps the point: it’s a realization that there are plenty of possibilities for new ways to look at things. We just need to notice them.

My funk wasn’t straight misoneism: I’m all for new forms else I wouldn’t be working here. But if we’re to create new forms that resonate as strongly as the physical book has been able to historically – a project that I suspect Brakhage considered himself engaged in – it’s just as important to find new ways to understand how what we’ve created works. And this is I think why the simple gesture of hitting the “pause” button in the middle of a film feels like something of a revelation to me, puncturing my December miasma. It’s not a blinding Damascene conversion, and that’s perhaps the point: it’s a realization that there are plenty of possibilities for new ways to look at things. We just need to notice them.

The late Guy Davenport, one of Brakhage’s friends and a kindred spirit, defended the unity of some of his own work – short stories that included his own drawings as an integral part of the story – by arguing that text, picture, and film weren’t in opposition, but were all images alike:

“A page, which I think of as a picture, is essentially a texture of images. . . . The text of a story is therefore a continuous graph, kin to the imagist poem, to a collage (Ernst, Willi Baumeister, El Lissitzky), a page of Pound, a Brakhage film.”

(from “Ernst Machs Max Ernst”, pp. 374-5 in The Geography of the Imagination)

Davenport’s declaration can be turned inside-out: we can now take a Brakhage film and read it as a series of pages. The word and the image still aren’t quite the same thing, but digital media allows us to think about them in some of the same ways. Watching with the pause button ready, we can scrutinize the composition of a single frame of film just as you might scrutinize an individual line or words in a poem, a page of a book.

Davenport’s declaration can be turned inside-out: we can now take a Brakhage film and read it as a series of pages. The word and the image still aren’t quite the same thing, but digital media allows us to think about them in some of the same ways. Watching with the pause button ready, we can scrutinize the composition of a single frame of film just as you might scrutinize an individual line or words in a poem, a page of a book.

Or again: historically, the coming of the book might be seen as freeing the reader from the dominion of time. The pre-literate can only listen to a text being read, while the literate is free to read at leisure. It’s a pause button, of a sort. Brakhage’s moth seems an apt tool for thinking here. I haven’t done the math, but I’d imagine the ratio of the length of a moth’s life to our own is about the same as the ratio of the moth’s size to our own. When we look at a moth, we see a being utterly bound by time. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

Most of the people reading this blog probably don’t give R. Kelly – the R&B singer known for his buttery voice and slippery morals – the attention that I do, which is completely understandable. But unfortunate, because he’s very much worth keeping an eye on. For the past six months, he’s been engaged in the most formally interesting experiment in pop music in a while. I’m referring, of course, to “Trapped in the Closet”. Bear with me a bit: while it might seem like I’m off on a frolic of my own, this will get around to having something to do with the future of the book.

Most of the people reading this blog probably don’t give R. Kelly – the R&B singer known for his buttery voice and slippery morals – the attention that I do, which is completely understandable. But unfortunate, because he’s very much worth keeping an eye on. For the past six months, he’s been engaged in the most formally interesting experiment in pop music in a while. I’m referring, of course, to “Trapped in the Closet”. Bear with me a bit: while it might seem like I’m off on a frolic of my own, this will get around to having something to do with the future of the book. For the next seven chapters, Kelly moved directly to video: he’s just released a DVD video of the first twelve chapters, where he and others act out the drama he’s narrating for thirty-nine minutes. New characters are introduced and the plot becomes steadily more labyrinthine (a midget and an allergy to cherries figure prominently) and fails to resolve much of anything. Kelly’s said to be busy thinking up a dozen more installments to the story. Through it all, the music remains the same; each episode is still three minute pop song, which do get played on the radio as such. Wikipedia does have a

For the next seven chapters, Kelly moved directly to video: he’s just released a DVD video of the first twelve chapters, where he and others act out the drama he’s narrating for thirty-nine minutes. New characters are introduced and the plot becomes steadily more labyrinthine (a midget and an allergy to cherries figure prominently) and fails to resolve much of anything. Kelly’s said to be busy thinking up a dozen more installments to the story. Through it all, the music remains the same; each episode is still three minute pop song, which do get played on the radio as such. Wikipedia does have a  An example at hand: a friend gave my girlfriend a copy of

An example at hand: a friend gave my girlfriend a copy of  It might be best explained by looking at the difference between Mastering the Art of French Cooking & Powell’s book. The former was conceived as a unified whole: it’s a single big idea, elucidated in steps, from the simple to the complicated. Later parts of that book are built upon the former: they don’t work well by themselves unless you’ve already absorbed the earlier information. Julie & Julia is constructed as a series of snapshots from the life of the author, each of which seeks to be individually interesting in and of itself. How does this play out in the pages of the book? An easy example: Powell’s sex life keeps popping up in a rather gratuitous fashion. The subject isn’t without relevance in a culinary work (

It might be best explained by looking at the difference between Mastering the Art of French Cooking & Powell’s book. The former was conceived as a unified whole: it’s a single big idea, elucidated in steps, from the simple to the complicated. Later parts of that book are built upon the former: they don’t work well by themselves unless you’ve already absorbed the earlier information. Julie & Julia is constructed as a series of snapshots from the life of the author, each of which seeks to be individually interesting in and of itself. How does this play out in the pages of the book? An easy example: Powell’s sex life keeps popping up in a rather gratuitous fashion. The subject isn’t without relevance in a culinary work (

Like the problem of hunger in the world, the problem with publishing in the United States isn’t one of supply but one of distribution.

Like the problem of hunger in the world, the problem with publishing in the United States isn’t one of supply but one of distribution.