Mitch Ratcliffe posted this very smart piece yesterday and gave permission to cross-post it on if:book.

How to create new reading experiences profitably

Concluding my summary of my recent presentation to a publishing industry group, begun here and continued here, we turn to the question of what to do to revitalize the publishing opportunity.

I wrote a lot about the idea of exploding the limitations of the book in the last installment. Getting beyond the covers. Turning from a distribution model to a reader-centric model. It’s simple to argue that change is needed and to say what needs changing. Here, I offer a few specific ideas about lines of research and development that I would like to see begun by publishers, who, if they wish to remain viable–let alone profitable–must undertake immediately. The change in book publishing will happen at a faster pace than the collapse of newspaper and music publishing did, making a collective effort at research and publication of the results for all to discuss and use, critical during the next 18 months. Think open sourcing the strategy, so that a thousand innovations can bloom.

Making books into e-books is not the challenge facing publishers and authors today. In fact, thinking in terms of merely translating text to a different display interface completely misses the problem of creating a new reading experience. Books have served well as, and will continue to be, containers for moving textual and visual information between places and across generations. They work. They won’t stop working. But when moving to a digital environment, books need to be conceived with an eye firmly set on the interactions that the text/content will inspire. Those interactions happen between the author and work, the reader and the work, the author and reader, among readers and between the work and various services, none of which exist today in e-books, that connect works to one another and readers in the community of one book with those in other book-worlds.

Just as with the Web, where value has emerged out of the connection of documents by publishers and readers–the Web is egalitarian in its connectivity, but still has some hierarchical features in its publishing technologies–books must be conceived of not just as a single work, but a collection of work (chapters, notes, illustrations, even video, if you’re thinking of a “vook”) that must be able to interact internally and with other works with which it can communicate over an IP network. This is not simply the use of social media within the book, though that’s a definite benefit, but making the book accessible for use as a medium of communication. Most communities emerge long after the initial idea that catalyzes them is first published.

These communications “hooks” revolve around traditional bibliographic practices, such as indexing and pagination for making references to a particular location in a book useful, as well as new functionality, such as building meta-books that combine the original text with readers’ notes and annotations, providing verification of texts’ authenticity and completeness, curation (in the sense that, if I buy a book today and invest of myself in it the resulting “version” of the book will be available to others as a public or private publication so that, for instance, I can leave a library to my kids and they can pass it along to their children) and preservation.

Think about how many versions of previously published books, going all the way back to Greek times, when books were sold on scrolls in stalls at Athens, have been lost. We treasure new discoveries of an author’s work. In a time of information abundance, however, we still dismiss all the other contributions that make a book a vital cultural artifact. Instead, we need to recognize that capturing the discussions around a book, providing access (with privacy intact) to the trails that readers have followed on their own or in discussions with others to new interpretations and uses for a text, and the myriad commentaries and marginalia that have made a book important to its readers is the new source of infinite value that can be provided as the experience we call “reading.” Tomorrow’s great literary discovery may not be an original work by a famous author, but a commentary or satire written by others in response to a book (as the many “…with sea monsters and vampires” books out there are beginning to demonstrate today). Community or, for lack of a better way of putting it, collaboration, is the source of emergent value in information. Without people talking about the ideas in a book, the book goes nowhere. This is why Cory Doctorow and Seth Godin’s advice about giving away free e-books makes so much sense, up to a point. Just turning a free ebook into the sale of a paper book leaves so much uninvented value on the table that, frankly, readers will never realize to get if someone doesn’t roll the experience up into a useful service.

The interaction of all the different “versions” of a book is what publishers can facilitate for enhanced revenues. This could also be accomplished by virtually anyone with a budget necessary to support a large community. The fascinating thing about the networked world, of course, is that small communities are what thrive, some growing large, so that anyone could become a “publisher” by growing a small community into a large or multi-book community.

Publishers can, though they may not be needed to, provide the connectivity or, at least, the “switchboards” that connect books. The BookServer project recently announced by The Internet Archive takes only one of several necessary steps toward this vision, though it is an important one: If realized, it will provide searchable indices and access to purchase or borrow any book for consumption in paper or a digital device. That’s big. It’s a huge project, but it leaves out all the content and value added to books by the public, by authors who release new editions (which need to be connected, so that readers want to understand the changes made between editions), and, more widely, the cultural echoes of a work that enhance the enjoyment and importance attributed to a work.

What needs to exist beside the BookServer project is something I would describe as the Infinite Edition Project. This would build on the universal index of books, but add the following features:

Word and phrase-level search access to books, with pagination intact;

A universal pagination of a book based upon a definitive edition or editions, so that the books’ readers can connect through the text from different editions based on a curated mapping of the texts (this would yield one ISBN per book that, coupled with various nascent text indexing standards, could produce an index of a title across media);

Synchronization of bookmarks, notes and highlights across copies of a book;

A reader’s copy of each book that supported full annotation indexing, allowing any reader to markup and comment on any part of a book–the reader’s copy becomes another version of the definitive edition;

An authenticated sharing mechanism that blends reader’s copies of a book based on sharing permissions and, this is key, the ability to sell a text and the annotations separately, with the original author sharing value with annotators;

The ability to pass a book along to someone, including future generations–here, we see where a publisher could sell many copies of their books based on their promise to keep reader’s copies intact and available forever, or a lifetime;

An authentication protocol that validates the content of a book (or a reader’s copy), providing an “audit trail” for attribution of ideas–both authors and creative readers, who would be on a level playing field with authors in this scenario, would benefit, even if the rewards were just social capital and intellectual credit;

Finally, Infinite Edition, by providing a flourishing structure for author-reader and inter-generational collaboration, could be supported by a variety of business models.

One of the notions that everyone, readers and publishers included, have to get over is the idea of a universal format. Text these days is something you store but not something that is useful without metadata and application-layer services. Infinite Edition, as the illustration above shows, is a Web services-based concept that allows the text to move across devices and formats. It would include an API for synchronizing a reader’s copy of a book, as well as for publishers or authors to update or combine versions.

Done right, an Infinite Edition API would let a Kindle user share notes with a Nook user and with a community that was reading the book online; if, at some point, a new version of the book were to be printed, publishers could, with permission, augment the book with contributions of readers. Therein lies a defensible value-added service that, at the same time, is not designed to prevent access to books–it’s time to flip the whole notion of protecting texts on its head and talk about how to augment and extend texts. As I have written elsewhere over the years, this is a feature cryptographic technology is made to solve, but without the stupidity of DRM.

Granted, access to a book would still be on terms laid out by the seller (author, publisher or distributor, such as Amazon, which could sell the text with Kindle access included through its own secure access point to the Infinite Edition Web service) however, it would become an “open” useful document once in the owner’s hands. And all “owners” would be able to do much with their books, including share them and their annotations. Transactions would become a positive event, a way for readers to tap into added services around a book they enjoy.

Publishers must lead this charge, as I wrote last time, because distributors are not focused on the content of books, just the price. A smart publisher will not chase the latest format, instead she will emphasize the quality of the books offered to the market and the wealth of services those books make accessible to customers. This means many additive generations of development will be required of tool makers and device designers who want to capitalize on the functionality embedded in a well-indexed, socially enabled book. It will prevent the wasteful re-ripping of the same content into myriad formats in order to be merely accessible to different reader devices. And the publishers who do invent these services will find distributors as willing as ever to sell them, because a revived revenue model is attractive to everyone.

ePUB would be a fine foundation for an Infinite Edition project. So would plain text with solid pagination metadata. In the end, though, what the page is–paper or digital–will not matter as much as what is on the page. Losing sight of the value proposition in publishing, thinking that the packaging matters more than the content to be distributed, is what has nearly destroyed newspaper publishing. Content is king, but it is also coming from the masses and all those voices have individual value as great as the king. So, help pull these communities of thought and entertainment together to remain a vital contributor to your customers.

This raises the last challenge I presented during my talk. The entire world is moving to a market ideal of getting people what they want or need when they want or need it. Publishing is only one of many industries battling the complex strategic challenge of just-in-time composition of information or products for delivery to an empowered individual customer. This isn’t to say that it is any harder, nor any easier, to be a publisher today compared to say, a consumer electronics manufacturer or auto maker, only that the discipline to recognize what creates wonderful engaging experience is growing more important by the day.

As I intimated in the last posting, this presentation didn’t land me the job I was after. I came in second, which is a fine thing to do in such amazing times. Congratulations to Scott Lubeck, who was named today as executive director of the Book Industry Study Group. I have joined the BISG to be an activist member. I welcome contact from anyone wishing to discuss how the BISG or individual publishers can put these ideas into action, a little at a time or as a concerted effort to transform the marketplace.

Author Archives: bob stein

commentpress 3.1

My colleagues and I are very happy to announce a completely re-vamped version of CommentPress. Available for download at /commentpress/.

If you want to see the new version in action, check out Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology, and the Future of the Academy.

The CD-Companion to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony by Robert Winter

Robert Winter’s CD-Companion to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony was published twenty years ago this week. As you look at this promo piece it’s important to realize that the target machine for this title was a Macintosh with a screen resolution of 640×400 and only two colors — black and white. This video dates from 1993.

two anniversaries

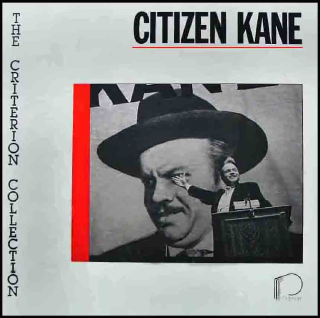

Just before Thanksgiving 1984, twenty-five years ago this week, The Criterion Collection was launched with the release of laserdisc editions Citizen Kane and King Kong.

In the video below critic Leonard Maltin introduces Criterion to his TV audience. Roger Smith who appears in the tape was one of Criterion’s co-founders. Ron Haver, who at the time was the film-curator at the LA County Museum of Art, made the first commentary track; a brilliant real-time introduction to the wonders of King Kong.

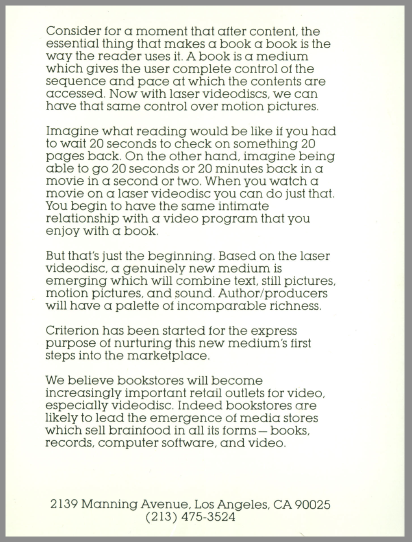

Although its since been changed, Criterion’s original logo from 1984 was based on the idea of a book turning into a disc. At the time it represented a conscious recognition that as microprocessors made their inevitable progression into all media devices, that the ways humans use and absorb media would change profoundly. The card below was distributed at the American Bookseller’s Convention (now the BEA) in June of 1984.

This week in 1988 also marks the publication of Voyager’s CD-Companion to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony by Robert Winter — the title that launched the brief cd-rom era of the early 90s. In honor of that anniversary, beginning tomorrow and continuing through the end of the year, we’ll start posting promo pieces for a number of Voyager’s cd-roms.

sea change

There was a book sale outside the library at UCLA today. lots of wonderful paperbacks for 50 cents each. a year ago i would have bought a bag full. today zero. why? i do almost all my novel reading now on my iPhone which is always with me and which makes it easy to read at the gym, as opposed to print books which never lie flat.

the android OS

two interesting pieces about the importance of the Android OS to “the future of the book”

http://ireaderreview.com/2009/10/27/androids-impact-on-ereading/

http://ebooktest.wordpress.com/2009/10/27/the-coming-android-mini-tablet-flood/

there’s no such thing as an amorphous “public”

Cody Brown, an NYU undergrad, just announced Kommons, an ambitious effort to build a new model of news gathering and presentation. I just read his blog post announcing the new venture, “A Public Can Talk To Itself” and find myself deeply disturbed. Although its no longer fashionable to say so, we live in a class society and our news organizations serve the needs of the classes they represent. Brown may very well go on to build the most successful news gathering operation of this new era, but whose interests will it serve? Brown’s idea of “the public” is clearly limited to those people who have access to technology, to the opportunity to learn the skills necessary to express themselves with that technology and the time to be a “citizen journalist.” Brown’s use of his mentor Clay Shirky’s automobile analogy confirms this when he writes: “A hundred years ago, back when cars were first being sold, you didn?t just buy one and drive it off the lot, the car itself was so complicated and difficult to manage that you hired a professional chauffeur who also served as a kind of mechanic.” I”m not sure how wealthy you had to be to buy the pre-Model T cars but I’m assuming it was a very small percentage of “the public.”

A last point, i find it fascinating and not insignificant that Brown has named his new venture, Kommons. I’m sure he just thinks it’s cute, but if he checks the Wikipedia, he’ll find there is a specific historical meaning often attached to the switch from K to C. I’m sure he didn’t set out consciously to trash the concept of the Commons but then i’m also sure he doesnt’ see any problems with his definition of public either.

From Wikipedia

“K” replacing “C” (article here)

Replacing the letter ?c? with ?k? in the first letter of a word came into use by the Ku Klux Klan during its early years in the mid to late 1800s. The concept is continued today within the ranks of the Klan. They call themselves “konservative KKK.”

In the 1960s and early 1970s in the United States, leftists, particularly the Yippies, sometimes used Amerika rather than “America” in referring to the United States.[1] It is still used as a political statement today.[2] It is likely that this was originally an allusion to the German spelling of America, and intended to be suggestive of Nazism, a hypothesis that the Oxford English Dictionary supports.

In broader usage, the replacement of the letter “C” with “K” denotes general political skepticism about the topic at hand and is intended to discredit or debase the term in which the replacement occurs. [9] Detractors sometimes spell former president Bill Clinton’s name as “Klinton” or “Klintoon”. [emphasis mine]

A similar usage in Spanish (and Portuguese too) is to write okupa rather than “ocupa” (often on a building or area occupied by squatters [10], referring to the name adopted by okupación activist groups), which is particularly remarkable because the letter “k” is rarely found in either Spanish or Portuguese words. It stems from Spanish anarchist and punk movements which used “k” to signal rebellion [3].

The letter “C” is also commonly changed to a “K” in a non-pejorative way in KDE, a desktop environment for Unix-like operating systems.

independent booksellers fight for their existence

October 22, 2009

The Board of Directors of the American Booksellers Association today sent the following letter to the U.S. Department of Justice requesting that it investigate practices by Amazon.com, Wal-Mart, and Target that it believes constitute illegal predatory pricing that is damaging to the book industry and harmful to consumers.

October 22, 2009

The Honorable Christine Varney

Assistant Attorney General

Antitrust Division

U.S. Department of Justice

950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Suite 3109

Washington, DC 20530

Molly Boast, Esquire

Deputy Assistant Attorney General for Civil Matters

Antitrust Division

U.S. Department of Justice

950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Room 3210

Washington, DC 20530

Dear Ms. Varney and Ms. Boast,

We are writing on behalf of the American Booksellers Association, a 109-year-old trade organization representing the nation’s locally owned, independent booksellers. A core part of our mission is devoted to making books as widely available to American consumers as possible. We ask that the Department of Justice investigate practices by Amazon.com, Wal-Mart, and Target that we believe constitute illegal predatory pricing that is damaging to the book industry and harmful to consumers. We are requesting a meeting with you to discuss this urgent issue at your earliest possible opportunity.

As reported in the consumer and trade press this past week, Amazon.com, WalMart.com, and Target.com have engaged in a price war in the pre-sale of new hardcover bestsellers, including books from John Grisham, Stephen King, Barbara Kingsolver, Sarah Palin, and James Patterson. These books typically retail for between $25 and $35. As of writing of this letter, all three competitors are selling these and other titles for between $8.98 and $9.00.

Publishers sell these books to retailers at 45% – 50% off the suggested list price. For example, a $35 book, such as Mr. King’s Under the Dome, costs a retailer $17.50 or more. News reports suggest that publishers are not offering special terms to these big box retailers, and that the retailers are, in fact, taking orders for these books at prices far below cost. (In the case of Mr. King’s book, these retailers are losing as much as $8.50 on each unit sold.) We believe that Amazon.com, Wal-Mart, and Target are using these predatory pricing practices to attempt to win control of the market for hardcover bestsellers.

It’s important to note that the book industry is unlike other retail sectors. Clothing, jewelry, appliances, and other commercial goods are typically sold at a net price, leaving the seller free to determine the retail price and the margin these products will earn. Because publishers print list prices indelibly on jacket covers, and because books are sold at a discount off that retail price, there is a ceiling on the amount of margin a book retailer can earn.

The suggested list price set by the publisher reflects manufacturing costs — acquisition, editing, marketing, printing, binding, shipping, etc. — which vary significantly from book to book. By selling each of these titles below the cost these retailers pay to the publishers, and at the same price as each other, and at the same price as all other titles in these pricing schemes, Amazon.com, Wal-Mart, and Target are devaluing the very concept of the book. Authors and publishers, and ultimately consumers, stand to lose a great deal if this practice continues and/or grows.

What’s so troubling in the current situation is that none of the companies involved are engaged primarily in the sale of books. They’re using our most important products — mega bestsellers, which, ironically, are the most expensive books for publishers to bring to market — as a loss leader to attract customers to buy other, more profitable merchandise. The entire book industry is in danger of becoming collateral damage in this war.

It’s also important to note that this episode was precipitated by below-cost pricing of digital editions of new hardcover books by Amazon.com, many of those titles retailing for $9.99, and released simultaneously with the much higher-priced print editions. We believe the loss-leader pricing of digital content also bears scrutiny.

While on the surface it may seem that these lower prices will encourage more reading and a greater sharing of ideas in the culture, the reality is quite the opposite. Consider this quote from Mr. Grisham’s agent, David Gernert, that appeared in the New York Times:

“If readers come to believe that the value of a new book is $10, publishing as we know it is over. If you can buy Stephen King’s new novel or John Grisham’s ‘Ford County’ for $10, why would you buy a brilliant first novel for $25? I think we underestimate the effect to which extremely discounted best sellers take the consumer’s attention away from emerging writers.”

For our members — locally owned, independent bookstores — the effect will be devastating. There is simply no way for ABA members to compete. The net result will be the closing of many independent bookstores, and a concentration of power in the book industry in very few hands. Bill Petrocelli, owner of Book Passage in Corte Madera, California, an ABA member, was also quoted in the New York Times:

“You have a choke point where millions of writers are trying to reach millions of readers. But if it all has to go through a narrow funnel where there are only four or five buyers deciding what’s going to get published, the business is in trouble.”

We would find these practices questionable were they taking place in the market for widgets. That they are taking place in the market for books is catastrophic. If left unchecked, these predatory pricing policies will devastate not only the book industry, but our collective ability to maintain a society where the widest range of ideas are always made available to the public, and will allow the few remaining mega booksellers to raise prices to consumers unchecked.

We urge that the DOJ investigate and request an opportunity to come to Washington to discuss this at your earliest convenience.

Sincerely,

ABA Board of Directors:

Michael Tucker, President (Books Inc.–San Francisco, CA)

Becky Anderson, Vice President (Anderson’s Bookshops–Naperville, IL)

Steve Bercu (BookPeople–Austin, TX)

Betsy Burton (The King’s English Bookshop–Salt Lake City, UT)

Tom Campbell (The Regulator Bookshop–Durham, NC)

Dan Chartrand (Water Street Bookstore–Exeter, NH)

Cathy Langer (Tattered Cover Book Store–Denver, CO)

Beth Puffer (Bank Street Bookstore–New York, NY)

Ken White (SFSU Bookstore–San Francisco, CA)

CC: Oren Teicher, CEO, American Booksellers Association

Len Vlahos, COO, American Booksellers Association

Owen M. Kendler, Esquire, Antitrust Division, U.S. Department of Justice

The internet Archive (and friends) announce Bookserver

Congratulations to Brewster Kahle and Peter Brantley of the Internet Archive for the very exciting, maybe sea-changing debut of the BookServer initiative. Possibly some real competition to Google, Amazon and Apple.

Here is a re-post of Fran Toolan’s detailed account of yesterday’s event.

The Day It All Changed

October 20, 2009 by ftoolan

OK, sounds dramatic, but trust me, mark down October 19, 2009 as a day to remember.

Rarely, in my career have I been “blown away” by a demonstration. Tonight, “blown away” doesn’t even begin to describe it. I should have seen it coming, but, I didn’t. I was completely blindsided. I was blindsided by the vision of Brewster Kahle, the raw brilliance of his team, and the entire group of individuals and companies who played a role in Brewster’s “convocation”.

What I saw, was many of the dreams and visions of e-book aficionados everywhere becoming a demonstrable reality tonight. I say ‘demonstrable’, because by Brewster’s own admission, it’s not ready for prime time, but the demonstration was enough to make my head spin with the possibilities. But you don’t really want to know that, so let me do my best to just report what I saw.

Let’s start from the beginning…

Tonight, Brewster Kahle, Internet Archive Founder and Chief Librarian, introduced what he calls his “BookServer” project. BookServer is a framework of tools and activities. It is an open-architectured set of tools that allow for the discoverability, distribution, and delivery of electronic books by retailers, librarians, and aggregators, all in a way that makes for a very easy and satisfying experience for the reader, on whatever device they want.

Now that may sound fairly innocuous, but let me try to walk through what was announced, and demonstrated (Please forgive me if some names or sequences are wrong, I’m trying to do this all from memory):

* Brewster announced that the number of books scanned at libraries all over the world has increased over the past year from 1 million books to 1.6 million books.

* He then announced that all of these 1.6 million books were available in the ePub format, making them accessible via Stanza on the iPhone, on Sony Readers, and many other reading devices in a way that allows the text to re-flow if the font has been changed.

* Next he announced that not only were these files available in ePub form, but that they were available in the “Daisy” format as well. Daisy is the format used to create Braille and Text to Speech software interpretations of the work.

* There were other statistics he cited related to other mediums such as 100,000 hours of TV recordings, 400,000 music recordings, and 15 billion (yes it’s a ‘b’) web pages that have been archived.

* He then choreographed a series of demonstrations. Raj Kumar from Internet Archive demonstrated how the BookServer technology can deliver books to the OLPC (One Laptop per Child) XO laptop, wirelessly. There are 1 million of these machines in the hands of underprivileged children around the world, and today they just got access to 1.6 million new books.

* Michael Ang of IA then demonstrated how a title in the Internet Archive which was available in the MOBI format could be downloaded to a Kindle – from outside the Kindle store – and then read on the Kindle. Because many of these titles were in the Mobi format as well, Kindle readers everywhere also have access to IA’s vast database.

* Next up, Mike McCabe of IA, came up and demonstrated how files in the Daisy format could be downloaded to a PC then downloaded to a device from Humana, specifically designed for the reading impaired. The device used Text-to-speech technology to deliver the content, but what was most amazing about this device was the unprecedented ease at which a sight impaired person could navigate around a book, moving from chapter to chapter, or to specific pages in the text.

* Brewster took a break from the demonstrations to elaborate a couple of facts, the most significant of which was the fact the books in the worlds libraries fall into 3 categories. The first category is public domain, which accounts for 20% of the total titles out there – these are the titles being scanned by IA. The second category is books that are in print and still commercially viable, these account for 10% of the volumes in the world’s libraries. The last category are books that are “out of print” but still in copyright. These account for 70% of the titles, and Brewster called this massive amount of information the “dead zone” of publishing. Many of these are the orphan titles that we’ve heard so much about related to the Google Book Settlement – where no one even knows how to contact the copyright holder. (To all of my friends in publishing, if you let these statistics sink in for a minute, your head will start to spin).

* Brewster went on to talk about how for any digital ecosystem to thrive, it must support not just the free availability of information, but also the ability for a consumer to purchase, or borrow books as well.

* At this point, Michael came back out and demonstrated – using the bookserver technology – the purchase of a title from O’Reilly on the Stanza reader on the iPhone – direct from O’Reilly – not from Stanza. If you are a reader, you may think that there is nothing too staggering about that, but if you are a publisher, this is pretty amazing stuff. Stanza is supporting the bookserver technology, and supporting the purchase of products direct from publishers or any other retailer using their technology as a delivery platform. (Again, friends in publishing, give that one a minute to sink in.)

* The last demonstration was not a new one to me, but Raj came back on and he and Brewster demonstrated how using the Adobe ACS4 server technology, digital books can be borrowed, and protected from being over borrowed from libraries everywhere. First Brewster demonstrated the borrowing process, and then Raj tried to borrow the same book but found he couldn’t because it was already checked out. In a tip of the hat to Sony, Brewster then downloaded his borrowed text to his Sony Reader. This model protects the practice of libraries buying copies of books from publishers, and only loaning out what they have to loan. (Contrary to many publishers fears that it’s too easy to “loan” unlimited copies of e-Books from libraries).

* In the last piece of the night’s presentation, Brewster asked many of the people involved in this project to come up and say a few words about why they were here, and what motivated them to be part of the project. The sheer number of folks that came out were as impressive as the different constituencies they represented. By the end of this the stage was full of people, including some I know, like Liza Daly (Three Press), Mike Tamblyn (Shortcovers), and Andrew Savikas (O’Reilly). Others, I didn’t know included Hadrien Gradeur (Feedbooks), the woman who invented the original screen for the OLPC, a published author, a librarian from the University of Toronto, Cartwright Reed from Ingram, and a representative from Adobe.

After the night was over, I walked all the way back to the Marina district where I was staying. The opportunities and implications of the night just absolutely made my head spin. I am completely humbled to be asked to be here and to witness this event.

In one fell swoop, the Internet Archive expanded the availability of books to millions of people who never had access before, bringing knowledge to places that had never had it. Who knows what new markets that will create, or more importantly what new minds will contribute to our collective wisdom as a result of that access. In the same motion, Brewster demonstrated a world where free can coexist with the library borrowing model, and with the commercial marketplace. Protecting the interests of both of those important constituencies in this ecosystem. He also, in the smoothest of ways, portrayed every ‘closed system’ including our big retail friends and search engine giants, as small potatoes.

I will have to post again about the implications of all this, but people smarter than me – many of whom I was able to meet today, will be far more articulate about what just happened. I’m still too blown away. I know this, it was a ‘game changer’ day. It may take a couple of years to come to full fruition, but we will be able to pinpoint the spot in history when it was all shown to be possible. I need to thank Peter Brantley for inviting (or should I say tempting) me to be there. Wow.

transliteracy research group launched

Sue Thomas and Kate Pullinger today announced the formation of The Transliteracy Research Group, a research-focused think-tank and creative laboratory. They define transliteracy as the ability to read, write and interact across a range of platforms, tools and media from signing and orality through handwriting, print, TV, radio and film, to digital social networks. The public face of the group resides on a new blog.