To fans long famished for a new Radiohead album (we’ve been waiting since ’03, with an admittedly lovely Thom Yorke solo effort last year to tide us over), there came today some very welcome news: their latest record, “In Rainbows,” is due to be released October 10th (hallelujah!). What’s worth noting here is how they’re doing it. With the release of their “COM LAG” EP in 2004, a collection of mainly b-sides from “Thief,” Radiohead wrapped up a 6-record contract with EMI. Rather than renewing or seeking a deal with another label, the band bucked the industry, opting to take charge of its own distribution. Well today they announced their first major act as their own boss, a simple website where you can pre-order (and soon purchase) their new album in two forms: 1) a beautiful collector’s discbox (pictured above) containing a CD (with bonus tracks and digital photos), two vinyl records, artwork and lyric booklets, all “encased in a hardback book and slipcase”; and 2) a digital download. Price of the discbox is 40 British pounds. Price of the download: it’s up to you.

Clearly, the band figures that these days mp3s fall more in the gift economy sector of making and distributing music. The big money is to be made off of touring, or, to a lesser degree, through the sale of lovingly crafted physical artifacts packed with all the juicy supplemental stuff that fans revel in. But yes, it’s true: a small transaction fee notwithstanding, the download can theoretically be obtained for nothing. I expect, though, that this good faith gesture might predispose fans (including this one) to voluntarily cough up 5 to 10 bucks (or rather, quid). It’s a very cool move on Radiohead’s part, one that acknowledges the fact that valuation of digital media is today very much an open question, and that figuring out the answer is best done not by the industries but through dialogue between the makers and the listeners (and all those folks in between).

Click the ?:

Another quick thought: by offering a pay-what-you-want download of the entire album, Radiohead is in a way cleverly pushing back the larger trend in music buying/sharing/pirating of disaggregation: i.e. tracks as the fundamental unit rather than whole records. They’re one of those bands whose music still justifies the album form and is crafted to fit that shape. Naturally they’ll do what they can to ensure that people experience it that way.

Author Archives: ben vershbow

penguin enlists amazon reviewers to sift fiction slush pile

In an interesting mashup of online social filtering and old-fashioned publishing, Penguin, Amazon and Hewlett Packard have joined forces to present a new online literary contest, the Amazon Breakthrough Novel Award. From the NY Times:

From today through Nov. 5, contestants from 20 countries can submit unpublished manuscripts of English-language novels to Amazon, which will assign a small group of its top-rated online reviewers to evaluate 5,000-word excerpts and narrow the field to 1,000. The full manuscripts of those semifinalists will be submitted to Publishers Weekly, which will assign reviewers to each. Amazon will post the reviews, along with excerpts, online, where customers can make comments. Using those comments and the magazine’s reviews, Penguin will winnow the field to 100 finalists who will get two readings by Penguin editors. When a final 10 manuscripts are selected, a panel including Elizabeth Gilbert, the author of the current nonfiction paperback best seller “Eat, Pray, Love,” and John Freeman, the president of the National Book Critics Circle, will read and post comments on the novels at Amazon. Readers can then vote on the winner, who will receive a publishing contract and a $25,000 advance from Penguin.

wikipedia’s growing pains

Insularity, editorial abuses, jargon, anonymity, power… some of the difficulties that beset the great public knowledge experiment of our day. Our friend Karen Schneider has a smart piece on Wikipedia’s “awkward adolescence.” Worth a read.

Like a startup maturing into a real business, Wikipedia’s corporate culture seems, at times, conflicted between its role as a harmless nouveau-digital experiment and its broader ambitions.

…The quieter rumblings about Wikipedia have less to do with vanity edits or poor maintenance of content than they do with the organization’s increasingly arbitrary editorial overrides and deletions and rapidly thickening in-group culture.

…Sock puppets, spy-versus-spy hijinks, and super-secret-vocabularies may be fine for a short-term experiment in information management; but Wikipedia positions itself not as a free encyclopedia, but the free encyclopedia. A FAQ claims, “We want Wikipedia to be around at least a hundred years from now, if it does not turn into something even more significant,” and Wikipedia’s fundraising page asks potential donors to “Imagine a world in which every single person can share freely in the sum of human knowledge.”

eeeeeeeeeee…..eeeeeeee…eeeee

Moby Dick Chapter 55 or 9200 times E”, 2004, graphite on hemp paper, 11 x 9″

In one of those odd, blogospheric delayed reactions, I just came across (via Information Aesthetics, via Kottke) a fabulous exhibit that took place this past March by an artist named Justin Quinn, who does beautiful, mysterious work with text. Quinn’s Moby-Dick series is made up of obsessively detailed prints and graphite drawings composed entirely of the letter E. Each E corresponds to a letter in a chapter of Melville’s book, so each piece is composed of literally thousands of characters. The effect is almost that of a mosaic or a concrete poem. This series was shown at MMGalleries in San Francisco and has since moved elsewhere (Miami possibly?), but there are still a number of images online (also here). Quinn explains his obsession with E:

The distance between reading and seeing has been an ongoing interest for me. Since 1998 I have been exploring this space through the use of letterforms, and have used the letter E as my primary starting point for the last two years. Since E is often found at the top of vision charts, I questioned what I saw as a familiar hierarchy. Was this letter more important than other letters? E is, after all, the most commonly used letter in the English language, it denotes a natural number (2.71828), and has a visual presence that interests me greatly. In my research E has become a surrogate for all letters in the alphabet. It now replaces the other letters and becomes a universal letter (or Letter), and a string of Es now becomes a generic language (or Language). This substitution denies written words their use as legible signifiers, allowing language to become a vacant parallel Language -? a basis for visual manufacture.

After months of compiling Es into abstract compositions through various systemic arrangements, I started recognizing my studio time as a quasi-monastic experience. There was something sublime about both the compositions that I was making and the solitude in which they were made. It was as if I were translating some great text like a subliterate medieval scribe would have years ago – ?with no direct understanding of the source material. The next logical step was to find a source. Herman Melville’s novel Moby Dick, a story rich in theology, philosophy, and psychosis provides me with a roadmap for my work, but also with a series of underlying narratives. My drawings, prints, and collages continue to speak of language and the transferal of information, but now as a conduit to Melville’s sublime narratives.

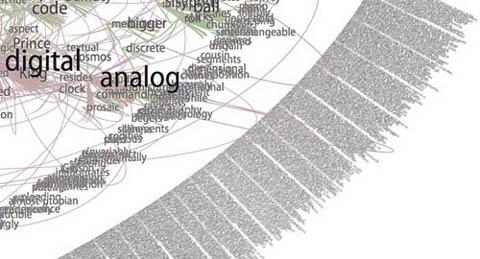

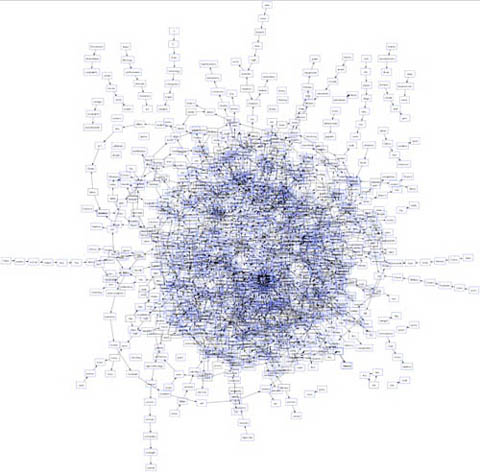

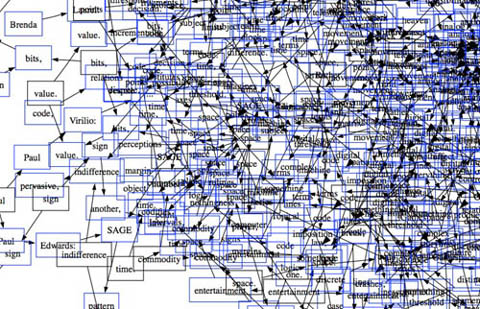

Gazing at these for a while (digital reproductions of course… and on my browser… and brought to my attention through technology blogs), I couldn’t help but start to draw some connections between Quinn’s work and computers. There’s plenty of digital artwork and visualization programs that render text into complex visual formations, sometimes with the intention of discovering new meanings and relationships, other times purely to play with form. Every now and then, someone manages to achieve both. This is a detail from Brad Paley’s rendering of Gamer Theory through his program Text Arc:

Others can be beautiful to handle, but are ultimately opaque, like Ben Fry’s “Valence”:

These two images are from another work submitted to our Gamer Theory visualization gallery, a map of nouns and verbs in Wark’s text (first is full, second is a detail). It’s pretty, but basically meaningless.

Quinn’s work is also difficult to penetrate, but something about it holds my attention. I’m not sure how aware Quinn is of the digital work being done today, but viewing his pieces against the contemporary technological backdrop, and his own self-described feeling of being the “subliterate medieval scribe” as he makes his minute articulations, my mind runs off in a number of directions. Seeing that his work is in a way “pixelated” – ?his Es a “basis for visual manufacture” – ?I imagine him as a sort of human computer – ?a monastic machine – ?processing (or intuiting) the text by infintessimal degrees through his own inner algorithm.

After all, a computer’s work is “subliterate.” Algorithms must be designed with intelligence, but the actual running of the program is physical, mindless. Viewed this way, Quinn’s work is like a dive into the mania of operations usually carried out with blazing speed by microprocessors. This is not to diminish it, or to call it cold and mechanical. Rather I’m pondering whether there is perhaps a spiritual dimension to the repetitive, sub-rational activities of our machines, which, if transposed to human scale, can become a sort of devotional exercise, like the routines of Buddhist monks, endlessly painting and carving Chinese characters in order to empty their minds (other links between monks and computers here and here).

What’s particularly evocative to me about the work, however, is how it treads the line between that meditative quality and the obsessive. There is something frightening about them (or about any kind of fanatically detailed artwork, or about computers for that matter), like the reams of psychotic babble typed out ceaselessly by Jack Nicholson in “The Shining.” Or is it Ahab’s vengeance algorithm we’re seeing, running on overdrive until the machine (or ship) crashes?

In the end, Quinn’s images are mysterious, his algorithm inscrutable, although my mind immediately goes to work trying to link up Melville’s themes and images to those endless strings of Es.

Here’s that first image again with a quote from the source text that seemed to me to connect. Chapter 55, “Of the Monstrous Pictures of Whales”:

Moby Dick Chapter 55 or 9200 times E”, 2004, graphite on hemp paper, 11 x 9″

But these manifold mistakes in depicting the whale are not so very surprising after all. Consider! Most of the scientific drawings have been taken from the stranded fish; and these are about as correct as a drawing of a wrecked ship, with broken back, would correctly represent the noble animal itself in all its undashed pride of hull and spars. Though elephants have stood for their full-lengths, the living Leviathan has never yet fairly floated himself for his portrait. The living whale, in his full majesty and significance, is only to be seen at sea in unfathomable waters; and afloat the vast bulk of him is out of sight, like a launched line-of-battle ship; and out of that element it is a thing eternally impossible for mortal man to hoist him bodily into the air, so as to preserve all his mighty swells and undulations.

This one is of chapter 71, “The Jeroboam’s Story” (I spoke briefly on the phone with one of the curators who told me that Quinn had explained this as an inverted halo, reflecting the anti-Christ-like character described in the chapter – ?I almost see an aerial view of a whale cutting through water):

Moby Dick Chapter 71 or 9,814 times E”, 2006, mixed media, 11 x 15″

…but straightway upon the ship’s getting out of sight of land, his insanity broke out in a freshet. He announced himself as the archangel Gabriel, and commanded the captain to jump overboard. He published his manifesto, whereby he set himself forth as the deliverer of the isles of the sea and vicar-general of all Oceanica. The unflinching earnestness with which he declared these things; – the dark, daring play of his sleepless, excited imagination, and all the preternatural terrors of real delirium, united to invest this Gabriel in the minds of the majority of the ignorant crew, with an atmosphere of sacredness. Moreover, they were afraid of him. As such a man, however, was not of much practical use in the ship, especially as he refused to work except when he pleased, the incredulous captain would fain have been rid of him; but apprised that that individual’s intention was to land him in the first convenient port, the archangel forthwith opened all his seals and vials – devoting the ship and all hands to unconditional perdition, in case this intention was carried out. So strongly did he work upon his disciples among the crew, that at last in a body they went to the captain and told him if Gabriel was sent from the ship, not a man of them would remain.

cellphone fiction in japan

Peter Brantley points to an interesting WSJ piece (free) on the explosion of Japanese cellphone fiction. These are works, often the length of novels, composed specifically for consumption via the phone’s tiny screen. In some cases, they are even written on the phone. Stories are written in terse, unadorned language, in chunks crafted specifically to fit on a single mobile screen. Dialog is favored heavily over narrative description, and from the short excerpts I’ve read, the aim seems to be to conjure cinematic imagery with the greatest economy of words. The WSJ reproduces this passage from Satomi Nakamura’s “To Love You Again”:

Peter Brantley points to an interesting WSJ piece (free) on the explosion of Japanese cellphone fiction. These are works, often the length of novels, composed specifically for consumption via the phone’s tiny screen. In some cases, they are even written on the phone. Stories are written in terse, unadorned language, in chunks crafted specifically to fit on a single mobile screen. Dialog is favored heavily over narrative description, and from the short excerpts I’ve read, the aim seems to be to conjure cinematic imagery with the greatest economy of words. The WSJ reproduces this passage from Satomi Nakamura’s “To Love You Again”:

Kin Kon Kan Kon (sound of school bell ringing)

(space)

The school bell rang

(space)

“Sigh. We’re missing class”

(space)

She said with an annoyed expression.

This novel clocks in at 200 pages, and was written entirely with Nakamura’s thumb!

About seven years ago, some of these works started making their way into print, initially through self-publishing websites like Maho i-Land. But the popularity of mobile novels soon caught the attention of mainstream publishers and numerous titles have been made into bona fide hits in print, some selling into the millions, with film adaptations, the whole bit.

But if any industry lesson can be taken from this mini case study of Japanese cellphone fic, it’s not the potential for crossover into print, but that emergent electronic literary forms will most likely find their economic model in services and subscriptions rather than in the sale of copies. The WSJ article suggests that the mobile lit genre exploded in Japan in no small part due to recent changes in service options from cellular providers.

About three years ago, phone companies began offering high-speed mobile Internet and affordable flat-rate plans for transmitting data. Users could then access the Internet as much as they wanted to for less than $50 a month.

The now-bustling Maho i-Land has six million members, and the number of mobile novels on its site has jumped, to more than a million today from about 300,000 before the flat-rate plans cut phone bills in half. According to industrywide data cited by Japan’s largest cellphone operator NTT DoCoMo Inc., sales from mobile-book and comic-book services are expected to more than double, to more than $200 million from about $90 million last year.

This would suggest that at least part of the reason cellphone novels haven’t taken off here in the States is the comparatively impoverished service we get from our mobile providers, and the often extortionist rates we pay. True, the mobile lit genre was already a phenomenon there before the rejiggering of service plans, which suggests there were preexisting cultural conditions that led to the emergence of the form: readers’ already well developed appetites for serial comics perhaps, or the peculiar intensity of keitai fetishism. In other words, improved telcom services in the States wouldn’t necessarily translate into a proliferation of cellphone novels, but other mobile media services would undoubtedly start to flourish. Broadband internet access is also pathetically slow in the US compared to countries in Europe and East Asia – ?the Japanese get service eight to 30 times faster than what we get over here. What other new media forms are being stifled by the crappiness of our connections?

commentpress in the chronicle

There’s a nice article about CommentPress this week in the Chronicle of Higher Education. Unfortunately, it’s subscription only. Here’s the link for those of you with access. I’m working on getting permission to offer a full PDF.

UPDATE: The Chronicle has kindly furnished us with a PDF. Help yourself.

the googlization of everything: a public writing begins

We’re very excited to announce that Siva’s new Google book site, produced and hosted by the Institute, is now live! In addition to being the seed of what will likely be a very important book, I’ll bet that over time this will become one of the best Google-focused blogs on the Web.

The Googlization of Everything: How One Company is Disrupting Culture, Commerce, and Community… and Why We Should Worry.

The book:

…a critical interpretation of the actions and intentions behind the cultural behemoth that is Google, Inc. The book will answer three key questions: What does the world look like through the lens of Google?; How is Google’s ubiquity affecting the production and dissemination of knowledge?; and how has the corporation altered the rules and practices that govern other companies, institutions, and states?

I have never tried to write a book this way. Few have. Writing has been a lonely, selfish pursuit for my so far. I tend to wall myself off from the world (and my loved ones) for days at a time in fits and spurts when I get into a writing groove. I don’t shave. I order pizza. I grumble. I ignore emails from my mother.

I tend to comb through and revise every sentence five or six times (although I am not sure that actually shows up in the quality of my prose). Only when I am sure that I have not embarrassed myself (or when the editor calls to threaten me with a cancelled contract – whichever comes first) do I show anyone what I have written. Now, this is not an uncommon process. Closed composition is the default among writers. We go to great lengths to develop trusted networks of readers and other writers with whom we can workshop – or as I prefer to call it because it’s what the jazz musicians do, woodshed our work.

Well, I am going to do my best to woodshed in public. As I compose bits and pieces of work, I will post them here. They might be very brief bits. They might never make it into the manuscript. But they will be up here for you to rip up or smooth over.

That’s the thing. For a number of years now I have made my bones in the intellectual world trumpeting the virtues of openness and the values of connectivity. I was an early proponent of applying “open source” models to scholarship, journalism, and lots of other things.

And, more to the point: One of my key concerns with Google is that it is a black box. Something that means so much to us reveals so little of itself.

So I would be a hypocrite if I wrote this book any other way. This book will not be a black box.

commentpress in the classroom 2

There are a couple of nice classroom implementations of CommentPress that I wanted to share, one that we set up by request, another done independently.

1. The first is an edition of Dante’s Inferno (Longfellow translation) for a literature seminar at the Pacific Northwest College of Art, “The Seven Deadly Sins,” taught by Trevor Dodge.

2. The second is “Man-Computer Symbiosis,” a seminal text in the history of computing by J.C.R. Licklider for a Harvard History of Science course, “Introduction to the History of Software and Networks”. This was brought to my attention by the teacher, Christopher Kelty, a professor of anthropology at Rice University, who is teaching this term at Harvard.

It’s still early in the semester but you can already see a substantial amount of discussion unfolding on both sites (be sure to use the “Browse Comments” navigation on the right sidebar to get a sense of where in the document discussion is happening, and who is participating). Kelty in particular encourages other knowledgeable readers from around the Web to make use of the Licklider text.

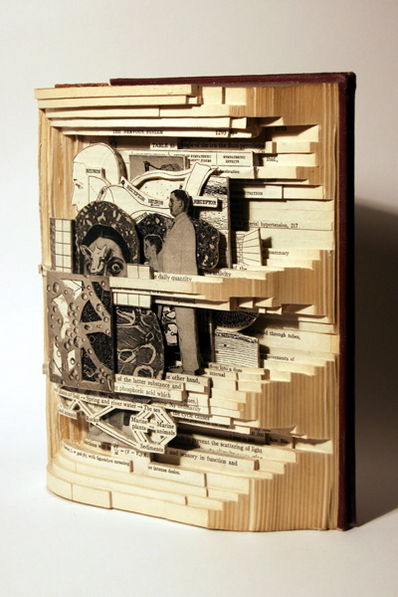

altered states

“The Physiological Basis of Medical Practice, 2006”, Altered book, 9 x 7-1/2 x 3-1/4 inches.

By Brian Dettmer at Haydee Rovirosa Gallery, New York.

(via Ron Silliman)

the new promiscuity

A couple more small items for the “content is free, networks are valuable” meme… these w/r/t television. First, this LA Times piece on CBS’s “new internet strategy”:

The idea is to let their online material be promiscuous: Instead of limiting their shows and other online video to CBS.com, the network is letting them couple with any website that people might visit.

“CBS is all about open, nonexclusive, multiple partnerships,” said Quincy Smith, president of CBS Interactive.

A big part of this strategy is building an “audience network,” and to this end the newly revamped CBS site provides a variety of fora – ?message boards, wikis, and user-generated media galleries – ?to try to capture some of the energy of its various fan communities. It’s a fine line to tread, since fan culture is almost by definition self-organizing and thrives on a sort of semi-autonomy. But perhaps this only because the broadcasters have hitherto kept their distance (the occasional self-defeating lawsuit notwithstanding). It’s an interesting (and somewhat yucky) question, and one that applies well beyond TV: to what extent can community be branded?

Compare this with NBC’s more retentive move toward quasi-openness, post-iTunes, with NBC Direct, a service that offers free downloads of shows with auto-destruct DRM that wipes files after a week. I don’t think either network’s got it yet, but these are interesting experiments to watch.

In light of this, it’s worth revisiting Mark Pesce’s 2005 talk, “Piracy is Good?”, available here on Google Video.