CommentPress, be it remembered, is a blog hack. A fairly robust one to be sure, and one which we expect to get significant near-term mileage out of, but still an adaptation of a relatively brittle publishing architecture. BookGlutton – ?a new community reading site that goes public beta next month – ?takes a shot at building social reading tools from scratch, and the first glimpses look promising. I’m still awaiting my beta tester account so it’s hard to say how well this actually works (and whether it’s Flash-based or Ajax-driven etc.), but a demo on their development blog walks through most of the social features of their browser-based “Unbound Reader.” They seem to have gotten a lot right, but I’m still curious to see how, if at all, they handle multimedia and interlinking between and within books. We’ll be watching this one closely…..Also, below the video, check out some explanatory material by BookGlutton’s creators, Aaron Miller and Travis Alber, that was forwarded to us the other day.

The first, the main BookGlutton website, is a catalog and community where users can upload work or select a piece of public domain writing, create reading groups and tag literature. The second part of the site – its centerpiece – is the Unbound Reader. It has a web-based format where users can read and discuss the book right inside the text. The Unbound Reader uses “proximity chat,” which allows users to discuss the book with other readers close to them in the text (thus focusing discussion, and, as an added benefit, keeping people from hearing about the end). It also has shared annotations, so people can leave a comment on any paragraph and other readers can respond. By encouraging users to talk in a context-specific way about what they’re reading, Bookglutton hopes to help those who want to talk about books (or original writing) with their friends (across cities, for example), students who want to discuss classic works (perhaps for a class), or writers who want to get feedback on their own pieces. Naturally, when the conversation becomes distracting, a user can close off the discussion without exiting the Reader.

Additionally, BookGlutton is working to facilitate adoption of on-line reading. Book design is an important aspect of the reader, and it incorporates design elements, like dynamic dropcaps. Moreover, the works presented in the catalog are standards-based (BookGlutton is an early adopter of the International Digital Publishing Forum’s .epub format for ebooks), and allows users to download a copy of anything they upload in this format for use elsewhere.

Author Archives: ben vershbow

of forests and trees

On Salon Machinist Farhad Manjoo considers the virtues of skimming and contemplates what is lost in the transition from print broadsheets to Web browsers:

It’s well-nigh impossible to pull off the same sort of skimming trick on the Web. On the Times site, stories not big enough to make the front page end up in one of the various inside section pages — World, U.S., etc. — as well as in Today’s Paper, a long list of every story published that day.

But these collections show just a headline and a short description of each story, and thus aren’t nearly as useful as a page of newsprint, where many stories are printed in full. On the Web, in order to determine if a piece is important, you’ve got to click on it — and the more clicking you’re doing, the less skimming.

Manjoo notes the recent Poynter study that used eye-tracking goggles to see how much time readers spent on individual stories in print and online news. The seemingly suprising result was that people read an average of 15% more of a story online than in print. But this was based on a rather simplistic notion of the different types of reading we do, and how, ideally, they add up to an “informed” view of the world.

On the Web we are like moles, tunneling into stories, blurbs and bliplets that catch our eye in the blitzy surface of home pages, link aggregators, search engines or the personalized recommendation space of email. But those stories have to vie for our attention in an increasingly contracted space, i.e. a computer screen -? a situation that becomes all the more pronounced on the tiny displays of mobile devices. Inevitably, certain kinds of worthy but less attention-grabby stories begin to fall off the head of the pin. If newspapers are windows onto the world, what are the consequences of shrinking that window to the size of an ipod screen?

This is in many ways a design question. It will be a triumph of interface design when a practical way is found to take the richness and interconnectedness of networked media and to spread it out before us in something analogous to a broadsheet, something that flattens the world into a map of relations instead of cramming it through a series of narrow hyperlinked wormholes. For now we are trying to sense the forest one tree at a time.

booker shortlist set free

CORRECTION: a commenter kindly points out that the Times jumped the gun on this one. What follows is in fact not true. Further clarification here.

The Times of London reports that the Man Booker Prize soon will make the full text of its winning and shortlisted novels free online. Sounds as though this will be downloads only, not Web texts. Unclear whether this will be in perpetuity or a limited-time offer.

Negotiations are under way with the British Council and publishers over digitising the novels and reaching parts – particularly in Africa and Asia – that the actual books would not otherwise reach.

Jonathan Taylor, chairman of The Booker Prize Foundation, said that the initiative was well advanced, although details were still being thrashed out.

The downloads will not impact on sales, it is thought. If readers like a novel tasted on the internet, they may just be inspired to buy the actual book.

the noble rot

Observe these gorgeous Rorshach mold blots blooming their way across the pages of old books. A video by Ben Hemmendinger, found on Vimeo.

The piece is titled “Edelfäule,” which a little Googling reveals to be German for “noble rot” -? “referring to BOTRYTIS CINEREA, the beneficial mold responsible for the TROCKENBEERENAUSLESE wines.” (Epicurious Wine Dictionary).

Thanks Alex for the link!

googlesoft gets the brush-off

This is welcome. Several leading American research libraries including the Boston Public and the Smithsonian have said no thanks to Google and Microsoft book digitization deals, opting instead for the more costly but less restrictive Open Content Alliance/Internet Archive program. The NY Times reports, and explains how private foundations like Sloan are funding some of the OCA partnerships.

commentpress and the communications circuit

So much to say about this but for the moment I only have time for a quick link. Our close friend and colleague Kathleen Fitzpatrick just published a must-read paper on MediaCommons, in conjunction with the Journal of Electronic Publishing. The paper is about CommentPress, but it’s a lot more than that. It’s a deep look at how Internet-based technologies hold the potential for a large-scale shift in scholarly communication toward a more communal model, taking CommentPress as just a small intimation of things possibly to come. What’s particularly gratifying for this reader is how Kathleen puts CommentPress in the larger context from which it was developed-?in particular, the rise of blogs and the move in some wired circles of the academy back to something resembling the coffeehouse model of scholarly conversation.

Two years ago we held an informal meeting of leading academic bloggers to discuss how this new Web-based conversation perhaps contained the seeds of broader change in scholarly publishing. Out of the ideas that were thrown about in that meeting grew our series of blog hacks that we loosely termed “networked books,” which, in turn, eventually evolved into CommentPress (not to mention MediaCommons). Kathleen’s paper brilliantly draws it all together.

Of course, CommentPress represents only the tiniest step forward. But perhaps out of Kathleen’s elegant, lucid argument we can draw the idea for the next experiment. To that end, I urge everyone to spend time on the CommentPress version (always nice when form engages so directly with content) and to continue the conversation there.

p.s. -? also feel free to look at an earlier version of this paper, which Kathleen workshopped in CommentPress.

the really modern library

This is a request for comments. We’re in the very early stages of devising, in partnership with Peter Brantley and the Digital Library Federation, what could become a major initiative around the question of mass digitization. It’s called “The Really Modern Library.”

Over the course of this month, starting Thursday in Los Angeles, we’re holding a series of three invited brainstorm sessions (the second in London, the third in New York) with an eclectic assortment of creative thinkers from the arts, publishing, media, design, academic and library worlds to better wrap our minds around the problems and sketch out some concrete ideas for intervention. Below I’ve reproduced some text we’ve been sending around describing the basic idea for the project, followed by a rough agenda for our first meeting. The latter consists mainly of questions, most of which, if not all, could probably use some fine tuning. Please feel encouraged to post responses, both to the individual questions and to the project concept as a whole. Also please add your own queries, observations or advice.

The Really Modern Library (basically)

The goal of this project is to shed light on the big questions about future accessibility and usability of analog culture in a digital, networked world.

We are in the midst of a historic “upload,” a frenetic rush to transfer the vast wealth of analog culture to the digital domain. Mass digitization of print, images, sound and film/video proceeds apace through the efforts of actors public and private, and yet it is still barely understood how the media of the past ought to be preserved, presented and interconnected for the future. How might we bring the records of our culture with us in ways that respect the originals but also take advantage of new media technologies to enhance and reinvent them?

Our aim with the Really Modern Library project is not to build a physical or even a virtual library, but to stimulate new thinking about mass digitization and, through the generation of inspiring new designs, interfaces and conceptual models, to spur innovation in publishing, media, libraries, academia and the arts.

The meeting in October will have two purposes. The first is to deepen and extend our understanding of the goals of the project and how they might best be achieved. The second is to begin outlining plans for a major international design competition calling for proposals, sketches, and prototypes for a hypothetical “really modern library.” This competition will seek entries ranging from the highly particular (for e.g., designs for digital editions of analog works, or new tools and interfaces for handling pre-digital media) to the broadly conceptual (ideas of how to visualize, browse and make use of large networked collections).

This project is animated by a strong belief that it is the network, more than the simple conversion of atoms to bits, that constitutes the real paradigm shift inherent in digital communication. Therefore, a central question of the Really Modern Library project and competition will be: how does the digital network change our relationship with analog objects? What does it mean for readers/researchers/learners to be in direct communication in and around pieces of media? What should be the *social* architecture of a really modern library?

The call for entries will go out to as broad a community as possible, including designers, artists, programmers, hackers, librarians, archivists, activists, educators, students and creative amateurs. Our present intent is to raise a large sum of money to administer the competition and to have a pool for prizes that is sufficiently large and meaningful that it can compel significant attention from the sort of minds we want working on these problems.

Meeting Agenda

Although we have tended to divide the Really Modern Library Project into two stages – the first addressing the question of how we might best take analog culture with us into the digitally networked future and the second, how the digitally networked library of the future might best be conceived and organized – these questions are joined at the hip and not easily or productively isolated from each other.

Realistically, any substantive answer to the question of how to re-present artifacts of analog culture in the digital network immediately raises issues ranging from new forms of browsing (in a social network) to new forms of reading (in a social network) which have everything to do with the broader infrastructure of the library itself.

We’re going to divide the day roughly in half, spending the morning confronting the broader conceptual issues and the afternoon discussing what kind of concrete intervention might make sense.

Questions to think about in preparation for the morning discussion:

* if it’s assumed that form and content are inextricably linked, what happens when we take a book and render it on a dynamic electronic screen rather than bound paper? same question for movies which move from the large theatrical presentation to the intimacy of the personal screen. interestingly the “old” analog forms aren’t as singular as they might seem. books are read silently alone or out loud in public; music is played live and listened to on recordings. a recording of a Beethoven symphony on ten 78rpm discs presents quite a different experience than listening to it on an iPod with random access. from this perspective how do we define the essence of a work which needs to be respected and protected in the act of re-presentation?

* twenty years ago we added audio commentary tracks to movies and textual commentary to music. given the spectacular advances in computing power, what are the most compelling enhancements we might imagine. (in preparation for this, you may find it useful to look at a series of exchanges that took place on the if:book blog regarding an “ideal presentation of Ulysses” (here and here).

* what are the affordances of locating a work in the shared social space of a digital network. what is the value of putting readers, viewers, and listeners of specific works in touch with each other. what can we imagine about the range of interactions that are possible and worthwhile. be expansive here, extrapolating as far out as possible from current technical possibilities.

* it seems to us that visualization tools will be crucial in the digital future both for opening up analog works in new ways and for browsing and making sense of massive media archives. if everything is theoretically connected to everything else, how do we make those connections visible in a way that illuminates rather than overwhelms? and how do we visualize the additional and sometimes transformative connections that people make individually and communally around works? how do we visualize the conversation that emerges?

* in the digital environment, all media break down into ones and zeros. all media can be experienced on a single device: a computer. what are the implications of this? what are the challenges in keeping historical differences between media forms in perspective as digitization melts everything together?

* what happens when computers can start reading all the records of human civilization? in other words, when all analog media are digitized, what kind of advanced data crunching can we do and what sorts of things might it reveal?

* most analog works were intended to be experienced with all of one’s attention, but the way we read/watch/listen/look is changing. even when engaging with non-networked media -? a paper book, a print newspaper, a compact disc, a DVD, a collection of photos -? we increasingly find ourselves Googling alongside. Al Pacino paces outside the bank in ‘dog day afternoon’ firing up the crowded street with “Attica! Attica!” I flip to Wikipedia and do quick read on the Attica prison riots. reading “song of myself” in “leaves of grass,” i find my way to the online Whitman archive, which allows me to compare every iteration of Whitman’s evolutionary work. or reading “ulysses” i open up Google Earth and retrace Bloom’s steps by satellite. while leafing through a book of caravaggio’s paintings, a quick google video search leads me to a related episode in simon schama’s “power of art” documentary series and a series of online essays. as radiohead’s new album plays, i browse fan sites and blogs for backstory, b-sides and touring info. the immediacy and proximity of such supplementary resources changes our relationship to the primary ones. the ratio of text to context is shifting. how should this influence the structure and design of future digital editions?

Afternoon questions:

* if we do decide to mount a competition (we’re still far from decided on whether this is the right approach), how exactly should it work? first off, what are we judging? what are we hoping to reward? what is the structure of this contest? what are the motivators? a big concern is that the top-down model -? panel of prestigious judges, serious prize money etc. -? feels very old-fashioned and ignores the way in which much of the recent innovation in digital media has taken place: an emergent, grassroots ferment… open source culture, web2.0, or what have you. how can we combine the heft and focused energy of the former with the looseness and dynamism of the latter? is there a way to achieve some sort of top-down orchestration of emergent creativity? is “competition” maybe the wrong word? and how do we create a meaningful public forum that can raise consciousness of these issues more generally? an accompanying website? some other kind of publication? public events? a conference?

* where are the leverage points are for an intervention in this area? what are the key consituencies, national vs. international?

* for reasons both practical and political, we’ve considered restricting this contest to the public domain. practical in that the public domain provides an unencumbered test bed of creative content for contributors to work with (no copyright hassles). political in that we wish to draw attention to the threat posed to the public domain by commercially driven digitization projects ( i.e. the recent spate of deals between Google and libraries, the National Archives’ deal with Footnote.com and Amazon, the Smithsonian with Showtime etc.). emphasizing the public domain could also exert pressure on the media industries, who to date have been more concerned with preserving old architectures of revenue than with adapting creatively to the digital age. making the public domain more attractive, more dynamic and more *usable* than the private domain could serve as a wake-up call to the big media incumbents, and more importantly, to contemporary artists and scholars whose work is being shackled by overly restrictive formats and antiquated business models. we’d also consider workable areas of the private domain such as the Creative Commons -? works that are progressively licensed so as to allow creative reuse. we’re not necessarily wedded to this idea. what do you think?

blogs… or just “the media”?

In the wake of Techmeme’s new top 100 Leaderboard site listing, IP Democracy wonders where have all the blogs gone?

Not only does the list include many old media mainstays such as the Wall Street Journal and New York Times, along with top trade publications such as Computerworld, but it is also heavily tilted toward new media “brands” formerly known as blogs such as GigaOm, TechCrunch and Engadget.

….All of these sites — TechCrunch, GigaOm, Engadget, and paidcontent.org, plus many others — are big deal media concerns, albeit still in their earliest stages of development, backed by venture capital and staffed by professional writers, editors, graphic designers and sales people. Nothing about them says “blogs,” if by blog you mean a true web log that reflects an individual’s take on a particular topic, or just life in general.

These guys are go-for-broke publishing concerns that face the same issues (staffing, accounting controls, growth strategies, compensation policies, editorial expertise, ad sales and so forth) as any bona fide media business. Robert Scoble, in a post that he entitled “TechMeme List Heralds Death of Blogging,” counted a mere 12 blogs in Techmeme’s leaderboard.

While the actual number of blogs on the list is probably higher than that, the point is: blogging seems to have been (and might still be) a mere waystation along the road to becoming a true publishing company and not quite the democratizing force in publishing that it once promised to be. Om and Rafat and TechCrunch’s Mike Arrington and everybody else used the rise of blogging software to inexpensively launch publications, just like any other publisher, and are now legitimate publishers.

I’d say independent blogging is still alive and well in the vast middle tier, but it’s true that things have become increasingly institutionalized at the top. But it’s not like we haven’t seen this before. Today’s newspapers are evolved from the 19th century upstart penny presses and pamphleteers who were the bloggers of their day… so it’s not particularly surprising that today’s top blogs are collectively becoming “the media” (history doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes). Also, best not to look at certain parts of the media ecology in isolation. The Leaderboard oligarchy sits atop a richly tangled bank of medium-trafficked and tiny niche sites, and millions of participating/linking/suggesting/commenting readers. Everything feeding everything else.

What’s most interesting to me is how blogs can develop their own imprints that start publishing well beyond the individual voice or voices that started them. if:book is becoming a sort of imprint in that way.

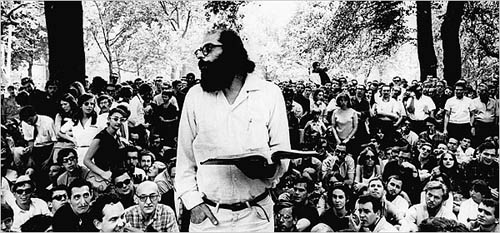

howling in the wilderness

Allen Ginsberg reading “Howl” in Washington Square in 1966. (Associated Press)

Yesterday marked the 50th anniversary of the famous court ruling in defense of Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” against charges of obscenity, citing the poem’s “redeeming social importance.” The Times reports how New York radio station WBAI had the idea of airing a recording of Ginsberg reading his poem to commemorate defense, but was ultimately dissuaded by its lawyers, who feared that an increasingly zealous FCC could fine the station out of existence. The poem did end up airing freely online on pacifica.org, where where the FCC stormtroopers have no jurisdiction. There, under the banner “Howl Against Censorship,” you can still hear it with comments by Lawrence Ferlingetti and other sages of the Beat era (there’s also a link to a full online text of the poem). Worth checking out.

What’s funny and more than a little sad about this story is its utter banality. This isn’t a drag-out battle against the thought police – ?it’s censorship drained of meaning. Because Janet Jackson accidentally let a boob fly at the 2004 Super Bowl, and a few others’ assorted lewd utterances on live TV, the humorless puritans at the FCC have knuckled down into zero tolerance mode. A few incidental curse words, not the actual substance of “Howl,” seem to be at issue here, and that’s what’s truly worrisome.

In ’57, there seemed to be something real at stake concerning free speech: not in the surface indecency of Ginsberg’s language, but in the heart of his protest and lament at the whole of American civilization. The Times quotes Ferlingetti:

Mr. Ferlinghetti, 88, who owns the landmark City Lights bookstore in San Francisco, said that when “Howl” was labeled obscene, first by United States Customs agents and then by the San Francisco police, it “wasn’t really the four-letter words.” He added, “It was that it was a direct attack on American society and the American way of life.”

If anything, this latter-day episode demonstrates how our culture is on auto pilot, that we’ve become so perfunctorily litigious in the mediation of language and symbols, that the masterpiece “Howl” might as well have been a recipe for pancakes or a wall message from MySpace. The poem’s gorgeous threat has been dulled by a larger and pervading numbness. Kudos, of course, to Pacifica for trying valiantly to break through it, but even if the poem had transmitted uncensored on FM radio, or had it been some other work, ten times as damning but without a trace of profanity, would anyone have even been awake enough to receive it?

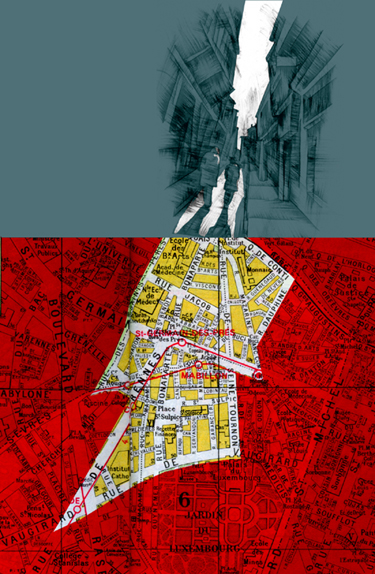

mckenzie wark on the situationists: this wednesday at columbia

If you’re in or around new york -? this promises to be a fascinating event. Plus Ken will be unveiling a new networked book project. Details further down.

50 Years of Recuperation: The Situationist International 1957-1972

The 2007 Buell Lecture, by McKenzie Wark

Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture

6.30-8.30PM Wednesday 3rd October 2007

Wood Auditorium, Avery Hall, Columbia University, New York

The Situationist International (1957-1972) bequeathed many key concepts to us, including psychogeography, the dérive, unitary urbanism, and of course the society of the spectacle. It also spawned at least one major work of critical and utopian architecture in Constant’s New Babylon. But rather than treat these as seductive historical curiosities, or as precursors to more “acceptable” notions, McKenzie Wark asks what might survive the recuperation of the Situationists and act as pointers to new practices. Rather than attempting to make an unbearable totality “sustainable,” perhaps we might pick up the thread of those who dared to negate this world as a whole and imagine it anew.

McKenzie will also unveil the website for his new ‘networked book’ version of his ongoing research on the Situationist International, under the working title of Totality for Kids. The website is designed by Chris France and features illustrations by Kevin C. Pyle.