Wikipedia is on the front page of the New York Times today, presumably for the first time. The article surveys recent changes to the site’s governance structure, most significantly the decision to allow administrators (community leaders nominated by their peers) to freeze edits on controversial pages. These “protection” and “semi-protection” measures have been criticized by some as being against the spirit of Wikipedia, but have generally been embraced as a necessary step in the growth of a collective endeavor that has become increasingly vast and increasingly scrutinized.

Browsing through a few of the protected articles — pages that have been temporarily frozen to allow time for hot disputes to cool down — I was totally floored by the complexity of the negotiations that inform the construction of a page on, say, the Moscow Metro. I attempted to penetrate the dense “talk” page for this temporarily frozen article, and it appears that the dispute centered around the arcane question of whether numbers of train lines should be listed to the left of a color-coded route table. Tempers flared and things apparently reached an impasse, so the article was frozen on June 10th by its administrator — a user by the name of Ezhiki (Russian for hedgehogs), who appears to be taking a break from her editing duties until the 20th (whether it is in connection to the recent metro war is unclear).

Look at Ezhiki’s profile page and you’ll see a column of her qualifications and ranks stacked neatly like merit badges. Little rotating star .gifs denote awards of distinction bestowed by the Wikipedia community. A row of tiny flag thumbnails at the bottom tells you where in the world Ezhiki has traveled. There’s something touching about the page’s cub scout aesthetic, and the obvious idealism with which it is infused. Many have criticized Wikipedia for a “hive mind” mentality, but here I see a smart individual with distinct talents (and a level head for conflict management), who has pitched herself into a collective effort for the greater good. And all this obsessive, financially uncompensated striving — all the heated “edit wars” and “revert wars” — for the production of something as prosaic as an encyclopedia, a mere doormat on the threshold of real knowledge.

But reworking the doormat is a project of massive proportions, and one that carries great political and social significance. Who should produce these basic knowledge resources and how should the kernel of knowledge be managed? These are the questions that Wikipedia has advanced to the front page of the newspaper of record. The mention of WIkipedia on the front of the Times signifies its crucial place in the cultural moment, and provides much-needed balance to the usual focus in the news on giant commercial players like Google and Microsoft. In a time of uncontrolled media oligopoly and efforts by powerful interests to mould the decentralized structure of the Internet into a more efficient architecture of profit, Wikipedia is using the new technologies to fuel a great humanistic enterprise. Wikipedia has taken the model of open source software and applied it to general knowledge. The addition of a few governance measures only serves to demonstrate the increasing maturity of the project.

Author Archives: ben vershbow

microsoft enlists big libraries but won’t push copyright envelope

In a significant challenge to Google, Microsoft has struck deals with the University of California (all ten campuses) and the University of Toronto to incorporate their vast library collections – nearly 50 million books in all – into Windows Live Book Search. However, a majority of these books won’t be eligible for inclusion in MS’s database. As a member of the decidedly cautious Open Content Alliance, Windows Live will restrict its scanning operations to books either clearly in the public domain or expressly submitted by publishers, leaving out the huge percentage of volumes in those libraries (if it’s at all like the Google five, we’re talking 75%) that are in copyright but out of print. Despite my deep reservations about Google’s ascendancy, they deserve credit for taking a much bolder stand on fair use, working to repair a major market failure by rescuing works from copyright purgatory. Although uploading libraries into a commercial search enclosure is an ambiguous sort of rescue.

congress passes telecom bill, breaks internet

The benighted and corrupt U.S. House of Representatives, well greased by millions of lobbying dollars, has passed (321-101) the new telecommunications bill, the biggest and most far-reaching since 1996, “largely ratifying the policy agenda of the nation’s largest telephone companies” (NYT). A net neutrality amendment put forth by a small band of democrats was readily defeated, bringing Verizon, Bell South, AT&T and the rest of them one step closer to remaking America’s internet in their own stupid image.

shirky (and others) respond to lanier’s “digital maoism”

Clay Shirky has written an excellent rebuttal of Jaron Lanier’s wrong-headed critique of collaborative peer production on the Internet: “Digital Maoism: The Hazards of the New Online Collectivism.” Shirky’s response is one of about a dozen just posted on Edge.org, which also published Lanier’s essay.

Shirky begins by taking down Lanier’s straw man, the cliché of the “hive mind,” or mob, that propels collective enterprises like Wikipedia: “…the target of the piece, the hive mind, is just a catchphrase, used by people who don’t understand how things like Wikipedia really work.”

He then explains how they work:

Wikipedia is best viewed as an engaged community that uses a large and growing number of regulatory mechanisms to manage a huge set of proposed edits. “Digital Maoism” specifically rejects that point of view, setting up a false contrast with open source projects like Linux, when in fact the motivations of contributors are much the same. With both systems, there are a huge number of casual contributors and a small number of dedicated maintainers, and in both systems part of the motivation comes from appreciation of knowledgeable peers rather than the general public. Contra Lanier, individual motivations in Wikipedia are not only alive and well, it would collapse without them.

(Worth reading in connection this is Shirky’s well-considered defense of Wkipedia’s new “semi-protection” measures, which some have decried as the death of the Wikipedia dream.)

I haven’t finished reading through all the Edge responses, but was particularly delighted by this one from Fernanda Viegas and Martin Wattenberg, creators of History Flow, a tool that visualizes the revision histories of Wikipedia articles. Building History Flow taught them how to read Wikipedia in a more sophisticated way, making sense of its various “arenas of context” — the “talk” pages and massive edit trails underlying every article. In their Edge note, Viegas and Wattenberg show off their superior reading skills by deconstructing the facile opening of Lanier’s essay, the story of his repeated, and ultimately futile, attempts to fix an innacuracy in his Wikipediated biography.

Here’s a magic trick for you: Go to a long or controversial Wikipedia page (say, “Jaron Lanier”). Click on the tab marked “discussion” at the top. Abracadabra: context!

These efforts can also be seen through another arena of context: Wikipedia’s visible, trackable edit history. The reverts that erased Lanier’s own edits show this process in action. Clicking on the “history” tab of the article shows that a reader — identified only by an anonymous IP address — inserted a series of increasingly frustrated complaints into the body of the article. Although the remarks did include statements like “This is Jaron — really,” another reader evidently decided the anonymous editor was more likely to be a vandal than the real Jaron. While Wikipedia failed this Jaron Lanier Turing test, it was seemingly set up for failure: would he expect the editors of Britannica to take corrections from a random hotmail.com email address? What he didn’t provide, ironically, was the context and identity that Wikipedia thrives on. A meaningful user name, or simply comments on the talk page, might have saved his edits from the axe.

Another respondent, Dan Gillmor, makes a nice meta-comment on the discussion:

The collected thoughts from people responding to Jaron Lanier’s essay are not a hive mind, but they’ve done a better job of dissecting his provocative essay than any one of us could have done. Which is precisely the point.

julian dibbell on GAM3R 7H30RY

Julian Dibbell has written a lovely little column on GAM3R 7H30RY in the Village Voice. He really gets what’s going on here, form-wise and content-wise:

In an age of the hyperlink and the blogosphere, there has been some question whether there’s a future of the book at all, but the warm, productive dialogue that’s shaping G4M3R 7H30RY may well be it.

Then again, if G4M3R 7H30RY’s argument is right, books may well have to cede their role as the preeminent means of understanding culture to another medium altogether: the video game. Wark sets out here on a quest for nothing less than a critical theory of games….and the mantric question he carries with him is “Can we explore games as allegories for the world we live in?” Turns out we can, but the complexity of contemporary games is such that no one mind is up to mapping it all, and Wark’s experiment in collaborative revision may be the best way to do the exploring.

physical books and networks

The Times yesterday ran a pretty decent article, “Digital Publishing Is Scrambling the Industry’s Rules”, discussing some recent experiments in book publishing online. One we’ve discussed here previously, Yochai Benkler’s The Wealth of Networks, which is available as both a hefty 500-page brick from Yale University Press and in free PDF chapter downloads. There’s also a corresponding readers’ wiki for collective annotation and discussion of the text online. It was an adventurous move for an academic press, though they could have done a better job of integrating the text with the discussion (it would have been fantastic to do something like GAM3R 7H30RY with Benkler’s book).

The Times yesterday ran a pretty decent article, “Digital Publishing Is Scrambling the Industry’s Rules”, discussing some recent experiments in book publishing online. One we’ve discussed here previously, Yochai Benkler’s The Wealth of Networks, which is available as both a hefty 500-page brick from Yale University Press and in free PDF chapter downloads. There’s also a corresponding readers’ wiki for collective annotation and discussion of the text online. It was an adventurous move for an academic press, though they could have done a better job of integrating the text with the discussion (it would have been fantastic to do something like GAM3R 7H30RY with Benkler’s book).

Also discussed is the new Mark Danielewski novel. His first book, House of Leaves, was published by Pantheon in 2000 after circulating informally on the web among a growing cult readership. His sophmore effort, due out in September, has also racked up some pre-publication mileage, but in a more controlled experiment. According to the Times, the book “will include hundreds of margin notes listing moments in history suggested online by fans of his work who have added hundreds of annotations, some of which are to be published in the physical book’s margins.” Annotations were submitted through an online forum on Danielewski’s web site, a forum that does not include a version of the text (though apparently 60 “digital galleys” were distributed to an inner circle of devoted readers).

The Times piece ends with an interesting quote from Danielewski, who, despite his roots in networked samizdat, is still ultimately focused on the book as a carefully crafted physical reading experience:

Mr. Danielewski said that the physical book would persist as long as authors figure out ways to stretch the format in new ways. “Only Revolutions,” he pointed out, tracks the experiences of two intersecting characters, whose narratives begin at different ends of the book, requiring readers to turn it upside down every eight pages to get both of their stories. “As excited as I am by technology, I’m ultimately creating a book that can’t exist online,” he said. “The experience of starting at either end of the book and feeling the space close between the characters until you’re exactly at the halfway point is not something you could experience online. I think that’s the bar that the Internet is driving towards: how to further emphasize what is different and exceptional about books.”

Fragmented as our reading habits (and lives) have become, there’s a persistent impulse, especially in fiction, toward the linear. Danielewski is probably right that the new networked modes of reading and writing might serve to buttress rather than unravel the old ways. Playing with the straight line (twisting it, braiding it, chopping it) is the writer’s art, and a front-to-end vessel like the book is a compelling restraint in which to work. This made me think of Anna Karenina, which is practically two novels braided together, the central characters, Anna and Levin, meeting just once, and then only glancingly.

I prefer to think of the networked book not as a replacement for print but as a parallel. What’s particularly interesting is how the two can inform one another, how a physical book can end up being changed and charged by its journey through a networked process. This certainly will be the case for the two books in progress the Institute is currently hosting, Mitch Stephens’ history of atheism and Ken Wark’s critical theory of video games. Though the books will eventually be “cooked” by a print publisher — Carroll & Graf, in Mitch’s case, and a university press (possibly Harvard or MIT), in Ken’s — they will almost certainly end up different for their having been networkshopped. Situating the book’s formative phase in the network can further boost the voltage between the covers.

An analogy. The more we learn about the evolution of biological life, the more we understand that the origin of species seldom follows a linear path. There’s a good deal of hybridization, random mutation, and general mixing. A paper recently published in Nature hypothesizes that the genetic link between humans and chimpanzees is at least a million years more recent than had previously been thought based on fossil evidence. The implication is that, for millennia, proto-chimps and proto-humans were interbreeding in a torrid cross-species affair.

An analogy. The more we learn about the evolution of biological life, the more we understand that the origin of species seldom follows a linear path. There’s a good deal of hybridization, random mutation, and general mixing. A paper recently published in Nature hypothesizes that the genetic link between humans and chimpanzees is at least a million years more recent than had previously been thought based on fossil evidence. The implication is that, for millennia, proto-chimps and proto-humans were interbreeding in a torrid cross-species affair.

Eventually, species become distinct (or extinct), but for long stretches it’s a story of hybridity. And so with media. Things are not necessarily replaced, but rather changed. Photography unleashed Impressionism from the paint brush; television, as Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s new book argues, acted as a foil for the postmodern American novel. The blog and the news aggregator may not kill the newspaper, but they will undoubtedly change it. And so the book. You see that glint in the chimp’s eye? A period of interbreeding has commenced.

in publishers weekly…

We’ve got a column in the latest Publishers Weekly. An appeal to publishers to start thinking about books in a network context.

what the book has to say

About a week ago, Jeff Jarvis of Buzz Machine declared the book long past its expiration date as a useful media form. In doing so, he summed up many of the intriguing possibilities of networked books:

The problems with books are many: They are frozen in time without the means of being updated and corrected. They have no link to related knowledge, debates, and sources. They create, at best, a one-way relationship with a reader. They try to teach readers but don’t teach authors. They tend to be too damned long because they have to be long enough to be books.

I’m going to tell him to have a look at GAM3R 7H30RY.

Since the site launched, discussion here at the Institute keeps gravitating back to the shifting role of the author. Integrating the text with the discussion as we’ve done, we’ve orchestrated a new relationship between author and reader, merging their activities within a single organ (like the systole-diastole action of a heart). Both activities are altered. The text, previously undisturbed except by the author’s hand, is suddenly clamorous with other voices. McKenzie finds himself thrust into the role of moderator, collaborating with the reader on the development of the book. The reader, in turn, is no longer a solitary explorer but a potential partner in a dialogue, with the author or with fellow readers.

Roger Sperberg elaborated upon this in a wonderful post about GAM3R 7H30RY on Teleread:

A serious text, published in a format designed to elicit comments by readers — this is new territory, since every subsequent reader has access to the initial text and to comments, improvements, criticisms, tangents and so on contributed by the body of readers-who-came-before, all incorporated into the, um, corpus.

This is definitely not the same as “I wrote it, they published it, individuals read and reviewed it, readers purchased it and shared their comments (some of them) with others in readers’ circles.” Even a few days after publication, there are plenty of contributions and perhaps those of Ray Cha, Dave Parry and Ben Vershbow are inseparable now from the initial comments of author McKenzie Wark, since I read them not after the fact but co-terminously (word? not “simultaneously” but “at the same time”). My own perception of the author’s ideas is shaped by the collaborating readers’ ideas even before it has solidified. What the author has to say has broadened almost immediately into what the book has to say.

Right around the same time, Sol Gaitan arrived independently at basically the same conclusion:

This brings me to pay attention to both, contents and process, which I find fascinating. If I choose to take part, my reading ceases to be a solitary act. This reminds me of the old custom of reading aloud in groups, when books were still a luxury. That kind of reading allowed for pauses, reflection and exchange. The difference now is that the exchange affects the book, but it’s not the author who chooses with whom he shares his manuscript, the manuscript does.

McKenzie (the author) then replied:

Not only is reading not here a solitary act, but nor is it conducted in isolation from the writer. It’s still an asymmetrical process. Someone asked me in email why it wasn’t a wiki. The answer to which is that this author isn’t that ready to play that dead.

Eventually, if selections from the comments are integrated in a subsequent version — either directly in the text or in some sort of appending critical section — Ken could find himself performing the role of editor, or curator. A curator of discussion…

Or perhaps that will be our job, the Institute. The shifting role of the editor/publisher.

so you’ve got a discussion going — how do you use it?

Alan Wexelblat has some interesting thoughts up on Copyfight about the GAM3R 7H30RY approach to writing.

Writers, particularly new ones, are often encouraged and bouyed up by physical writer’s groups, in which people co-critique works in progress. Some writing workshops/groups also include lectures from established authors and related well-known people in publishing. In SF/Fantasy, the Clarion SF&F Writers’ Workshop is well known and has graduated a number of folk who have gone on to great success.

So, can this model work online? I’m dubious. One of the things that makes a good writers’ group, and that makes Clarion the success it has been, is a rigorous screening process. You get into these things not just by having good intentions or a lot to say but by having valuable experience and insights to contribute. It’s unclear to me how one filters the mass audience of the Web into something resembling useful wisdom.

This is not a trivial question. Already, it’s all Ken can do to keep a handle on the various feedback loops spinning through the site. Separating the wheat from the chaff requires a great amount of time and attention on top of that. If we had unlimited time and resources, it would be interesting to play with some sort of collaborative filtering system for comments. What if readers had a way of advancing through a series of levels (appropriate to the game theme), gaining credibility as a respondent with each new level attained (like karma in Slashdot). These “advanced” readers would then have more authority to moderate other discussions, sharing some of the burden with the author.

On the other hand, perhaps a workshop is the wrong model. Maybe this is more like the writing of a massive wikipedia entry on games and game theory. One person writes most of it, but the audience participates in the edit and refinement process? It seems like that model might produce something more useful.

This is not headed for anything encyclopedic. Ken is still an individual voice and this book ultimately an expression of his unique critical view (the idea of writing any work of criticism collaboratively, the way one writes a Wikipedia aticle, is a little odd). But Ken is getting useful work out of his readers (who, among other things, are good at spotting typos). There’s definitely some of that wiki work ethic at play.

Another thing he’s after is good testimonials about what it feels like to play these games. We already got a fabulous little description of the experience of Katamari Damacy. Hopefully the first of many. So this is also another way of doing interviews for the book, in the setting most familiar to gamers talking about gaming: an online discussion forum.

accesselujah!!!

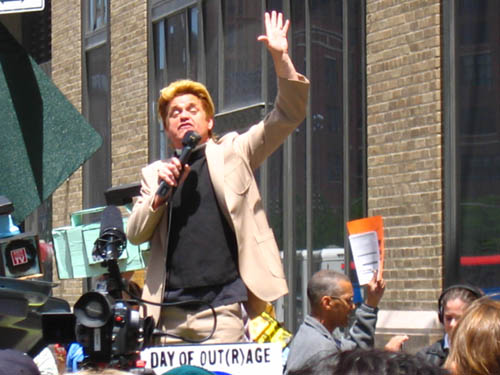

if:book took to the streets yesterday at the National Day of Out(r)age protest outside Verizon world headquarters in downtown Manhattan. Here’s Reverend Billy, a local performance artist/activist who styles himself as a televangelist (he’s sort of annoying, but entertaining in small doses). His cry: “accesselujah!”

The crowd was quite small, fenced in along a single block outside the towering Verizon building. A few handfuls of grassroots media folks and other miscellanies gathered to protest the odious COPE HR5252 legislation, which threatens net neutrality and PEG (Public, Educational and Governmental) Access channels on TV. The mission is to rally one person for every telecom/cableco lobbying dollar. Judging by yesterday’s turnout, things aren’t looking so hot.

I kinda liked this sign though: