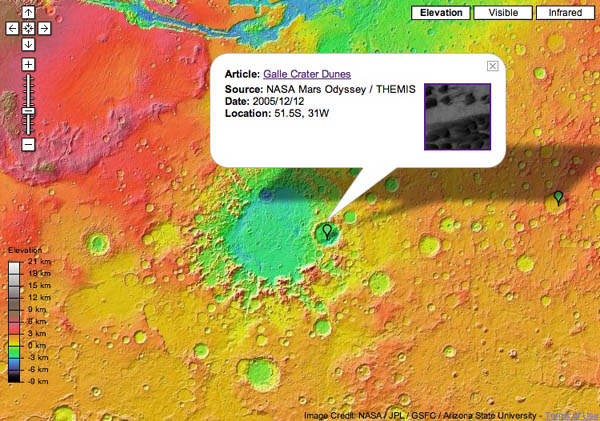

Apparently, this came out in March, but I ‘ve only just stumbled on it now. Google has a version of its maps program for the planet Mars, or at least the part of if explored and documented by the 2001 NASA Mars Odyssey mission. It’s quite spectacular, especially the psychedelic elevation view:

There’s also various info tied to specific coordinates on the map: location of dunes, craters, planes etc., as well as stories from the Odyssey mission, mostly descriptions of the Martian landscape. It would be fun to do an anthology of Mars-located science fiction with the table of contents mapped, or an edition of Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles. Though I suppose there’d a fair bit of retrofitting of the atlas to tales written out of pure fancy and not much knowledge of Martian geography (Marsography?). If nothing else, there’s the seeds of a great textbook here. Does the Google Maps API extend to Mars, or is it just an earth thing?

Author Archives: ben vershbow

can advertising liberate textbooks?

The aptly named Freeload Press is giving away free PDFs (free as in free beer, or free market) of over 100 textbooks titles (mostly in business and finance, though more is planned). All students have to do is fill out an online survey and then the download is theirs, to use on a computer or to print out. Where does the money come from? Ads. Ads in the pages of the textbooks.

An ad for FedEx Kinkos in a sample Freeload textbook. Hmmm, wonder where I should get this thing printed?

Ads in textbooks is undoubtedly a depressing thought. Even more depressing, though, is the outlandish cost of textbooks, and the devious, often unethical, ways that textbook publishers seek to thwart the used book market. This Washington Post story gives a quick overview of the problem, and profiles the St. Paul, Minnesota-based Freeload.

Though making textbooks free to students is an admirable aim, simply shifting the cost to advertisers is not a good long-term solution, further eroding as it does the already much-diminished borderline between business and education (I suppose, though, that ads in business ed. textbooks in some ways enact the underlying precepts being taught). There are far better ideas out there for, as Freeload promises, “liberating the textbook” (a slogan that conjures the Cheney-esque: the textbooks will greet us as liberators).

One of them comes from Adrian Lopez Denis, a PhD candidate in Latin American history at UCLA. I’m reproducing a substantial chunk of a brilliant comment he posted last month to the Chronicle of Higher Ed’s Wired Campus blog in response to their coverage of our announcement of MediaCommons. We just met with Adrian while in Los Angeles and will likely be collaborating with him on a project based on the ideas below. Basically, his point is that teachers and students should collaborate on the production of textbooks.

Students are expected to produce a certain amount of pages that educators are supposed to read and grade. There is a great deal of redundancy and waste involved in this practice. Usually several students answer the same questions or write separately on the same topic, and the valuable time of the professionals that read these essays is wasted on a rather repetitive task.

[…]

As long as essay writing remains purely an academic exercise, or an evaluation tool, students would be learning a deep lesson in intellectual futility along with whatever other information the course itself is trying to convey. Assuming that each student is writing 10 pages for a given class, and each class has an average of 50 students, every course is in fact generating 500 pages of written material that would eventually find its way to the campus trashcans. In the meantime, the price of college textbooks is raising four times faster that the general inflation rate.

The solution to this conundrum is rather simple. Small teams of students should be the main producers of course material and every class should operate as a workshop for the collective assemblage of copyright-free instructional tools. Because each team would be working on a different problem, single copies of library materials placed on reserve could become the main source of raw information. Each assignment would generate a handful of multimedia modular units that could be used as building blocks to assemble larger teaching resources. Under this principle, each cohort of students would inherit some course material from their predecessors and contribute to it by adding new units or perfecting what is already there. Courses could evolve, expand, or even branch out. Although centered on the modular production of textbooks and anthologies, this concept could be extended to the creation of syllabi, handouts, slideshows, quizzes, webcasts, and much more. Educators would be involved in helping students to improve their writing rather than simply using the essays to gauge their individual performance. Students would be encouraged to collaborate rather than to compete, and could learn valuable lessons regarding the real nature and ultimate purpose of academic writing and scholarly research.

Online collaboration and electronic publishing of course materials would multiply the potential impact of this approach.

What’s really needed is for textbooks to liberated from textbook publishers. Let schools produce their own knowledge, and spread the wealth.

encouraging

The following was posted on Sunday by Mitch Stephens on Without Gods (for those of you still unfamiliar with it, Without Gods is the public work diary for Mitch’s forthcoming history of atheism, which we’ve been hosting for the past eight months — wow, has it been that long?!).

The following was posted on Sunday by Mitch Stephens on Without Gods (for those of you still unfamiliar with it, Without Gods is the public work diary for Mitch’s forthcoming history of atheism, which we’ve been hosting for the past eight months — wow, has it been that long?!).

Thanks

The quality of the comments here lately has seemed, to me, extraordinarily high.

One of the purposes of blogging a book as it is being written is to have ideas tested and, possibly, sharpened, transformed or overturned. This has repeatedly occurred — although I have not often weighed in with comments of my own acknowledging that. Please take this as a blanket acknowledgement and expression of appreciation.

GAM3R 7H30RY may be flashier, and more technically ambitious, but in many ways Without Gods has been a more revelatory experiment in networked writing. As Mitch acknowledges, the sustained activity, and quality, of the comment streams has been impressive, and above all, interesting to read. It’s fascinating to follow this evolving collaboration between author and reader, and to watch Mitch come into his own as a skilled moderator of blog-based discussion. It remains to be seen how these conversations will end up shaping the finished book, but for some examples of a tangible collaboration taking place, take a look at these recent “Author Needs Advice” posts (part 1, part 2), in which Mitch asks for feedback on specific sections of the work-in-progress. Whatever the outcome, it’s clear that this reconfiguration of the writing process is yielding real rewards.

notable wikipedians

Simon Pulsifer: “the king of Wikipedia”

“He lives at home and doesn’t have a girlfriend.”

(photo: Bill Grimshaw/The Globe and Mail)

I just came across this story in The Toronto Globe and Mail about a young man from Ottawa by the name of Simon Pulsifer who, under the moniker SimonP, is Wikipedia’s most prolific contributor: “with 78,000 entries edited and 2,000 to 3,000 new articles to his name. He can’t remember the exact number.”

Pulsifer is also the subject of an article in Wikipedia, which, like many of the vanity stubs devoted to the encyclopedia’s editors, was nominated for deletion, only to be voted a keeper after some discussion. Justin Hall, a colleague of ours at USC, often cited as the first blogger, and a distinguished Wikipedian in his own right, offered the following in defense of the Pulsifer page:

As Wikipedia grows in importance and global reach, the most passionate participants in this collective editing experiment become important global intellectuals. Simon Pulsifer is one of the first public Wikipedians – with a great number of articles, a passion for editing under-developed subjects, and a strong sense of the mission of Wikipedia. He might not care to have an article about him here, but already mainstream media outlets (a Canadian newspaper) and online news sites (digg.com) have saluted his work. That attention and importance is only likely to increase. Let’s keep this article because Simon Pulsifer has already reached a greater number of people than many of the “historic” individuals described on Wikipedia.

Both Pulsifer and Hall are members of what could be considered the Wikipedia elite, the “notable Wikipedians“. Many of these probably deserve a good share of the credit for Wikipedia’s success. Now, though, I’m more interested in how Wikipedia’s corps of editors might gradually expand to include a greater slice of the public: teacher, students, and people from all walks of life.

Zealous Wikipedia hobbyists like Pulsifer, god love ’em, will hopefully, over time, be considered the exceptions that prove the general rule of participation: editing as a more modest pursuit that one builds into one’s intellectual life and lifelong learning regimen. If enough people begin to take part in this way, Wikipedia could become more diverse, more exhaustive, and more accurate than it already is. The Pulsifers and Halls might end up being its governors, its civil servants, its politicians. Of course, it is the process that is most important: the kind of civic participation and engagement over points of dissent that collaborating on Wikipedia entails. Bob explained this eloquently last week. Or, as Pulsifer describes it:

You write an article and you think you’ve made it as good as it can be and then you put it out there for everyone to see and edit. And within just a few minutes, you have started a dialogue over how best to represent a subject.

pinkwater dips his toes (and quill) into the web

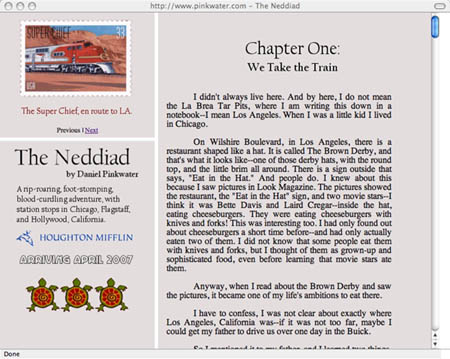

The Institute is back in Los Angeles at USC, our home away from home in academe, where, for the next two days, we’re holding an introductory “boot camp” session with a small group of professors who will begin using Sophie in their classes this fall. USC is just southwest of downtown LA, right near the La Brea Tar Pits, which, incidentally, is the starting point of the latest book by one of my favorite childhood writers, Daniel Manus Pinkwater, who, I just read in Publishers Weekly, is publishing his newest book online.

Pinkwater, author of Lizard Music, The Hoboken Chicken Emergency, the Snarkout Boys novels, and many, many others, is publishing his newest effort, The Neddiad, “a rip-roaring, foot-stomping, blood-curdling adventure, with station stops in Chicago, Flagstaff, and Hollywood, California,” free on his website as a serial.

With the blessing of his publisher, Houghton Mifflin, Pinkwater has set up a simple, very readable little site, where readers can imbibe the book, in slightly raw form, one chapter per week.

What we are presenting is the original author’s manuscript. There are some typos, and editorial corrections, and changes by me are not included. So the published book will be slightly different. I am a careful writer, and worked with a fine editor, so the differences are not great, but I thought it might be of interest for some to see what the book was like when handed in.

In many ways, this is a very PInkwater move — plugging his book into an electrical socket and watching it glow. There’s also a discussion forum, so it’s something of a networked book:

Readers are welcome to post comments, criticisms, complaints, and exchange remarks–a link will be provided, and I may periodically chime in to discuss and argue with the posters.

Pinkwater told PW:

When I was younger a circus hand showed me how they let kids sneak into the circus. If they were bold enough to try, they got to stay. I’m trying to keep that feeling for kids with this project. It lets kids sneak into the tent. We’re deliberately keeping it from looking slick; there are no ads. Of course, it’s with Houghton Mifflin’s kind permission that we can offer this, but it’s still a bit of homebrew, slightly different from the finished version. We hope that the readers who enjoy what they find online will want to buy the book, too.

If nothing else, Pinkwater has grasped an important (and counterintuitive) principle of web publishing: that giving stuff away can help sell books. It helps facilitate a discussion about that stuff, and can make readers feel better disposed toward you and your work (i.e. more likely to buy it in print). One chapter per week is a rather dribbling pace, however (recall the somewhat disingenuous serialization of Pulse by FSG), and might be a bit like Chinese water torture for Pinkwater’s ardent fans. But we’ll see.

the trouble with wikis in china

I’ve just been reading about this Chinese online encyclopedia, modeled after Wikipedia, called “e-Wiki,” which last month was taken offline by its owner under pressure from the PRC government. Reporters Without Borders and The Sydney Morning Herald report that it was articles on Taiwan and the Falun Gong (more specifically, an article on an activist named James Lung with some connection to FG) that flagged e-Wiki for the censors.

Baidu: the heavy paw of the state.

Meanwhile, “Baidupedia,” the user-written encyclopedia run by leading Chinese search engine Baidu is thriving, with well over 300,000 articles created since its launch in April. Of course, “Baidu Baike,” as the site is properly called, is heavily censored, with all edits reviewed by invisible behind-the-scenes administrators before being published.

Wikipedia’s article on Baidu Baike points out the following: “Although the earlier test version was named ‘Baidu WIKI’, the current version and official media releases say the system is not a wiki system.” Which all makes sense: to an authoritarian, wikis, or anything that puts that much control over information in the hands of the masses, is anathema. Indeed, though I can’t read Chinese, looking through it, pages on Baidu Baike do not appear to have the customary “edit” links alongside sections of text. Rather, there’s a text entry field at the bottom of the page with what seems to be a submit button. There’s a big difference between a system in which edits are submitted for moderation and a totally open system where changes have to be managed, in the open, by the users themselves.

All of which underscores how astonishingly functional Wikipedia is despite its seeming vulnerability to chaotic forces. Wikipedia truly is a collectively owned space. Seeing how China is dealing with wikis, or at least, with their most visible cultural deployment, the collective building of so-called “reliable knowledge,” or encyclopedias, underscores the political implications of this oddly named class of web pages.

Dan, still reeling from three days of Wikimania, as well as other meetings concerning MIT’s One Laptop Per Child initiative, relayed the fact that the word processing software being bundled into the 100-dollar laptops will all be wiki-based, putting the focus on student collaboration over mesh networks. This may not sound like such a big deal, but just take a moment to ponder the implications of having all class writing assignments being carried out wikis. The different sorts of skills and attitudes that collaborating on everything might nurture. There a million things that could go wrong with the One Laptop Per Child project, but you can’t accuse its developers of lacking bold ideas about education.

But back to the Chinese. An odd thing remarked on the talk page of the Wikipedia article is that Baidu Baike actually has an article about Wikipedia that includes more or less truthful information about Wikipedia’s blockage by the Great Firewall in October ’05, as well as other reasonably accurate, and even positive, descriptions of the site. Wikipedia contributor Miborovsky notes:

Interestingly enough, it does a decent explanation of WP:NPOV (Wikipedia’s Neutral Point of View policy) and paints Wikipedia in a positive light, saying “its activities precisely reflects the web-culture’s pluralism, openness, democractic values and anti-authoritarianism.”

But look for Wikipedia on Baidu’s search engine (or on Google, Yahoo and MSN’s Chinese sites for that matter) and you’ll get nothing. And there’s no e-Wiki to be found.

u.c. offers up stacks to google

Less than two months after reaching a deal with Microsoft, the University of California has agreed to let Google scan its vast holdings (over 34 million volumes) into the Book Search database. Google will undoubtedly dig deeper into the holdings of the ten-campus system’s 100-plus libraries than Microsoft, which is a member of the more copyright-cautious Open Content Alliance, and will focus primarily on books unambiguously in the public domain. The Google-UC alliance comes as major lawsuits against Google from the Authors Guild and Association of American Publishers are still in the evidence-gathering phase.

Meanwhile, across the drink, French publishing group La Martiniè re in June brought suit against Google for “counterfeiting and breach of intellectual property rights.” Pretty much the same claim as the American industry plaintiffs. Later that month, however, German publishing conglomerate WBG dropped a petition for a preliminary injunction against Google after a Hamburg court told them that they probably wouldn’t win. So what might the future hold? The European crystal ball is murky at best.

During this period of uncertainty, the OCA seems content to let Google be the legal lightning rod. If Google prevails, however, Microsoft and Yahoo will have a lot of catching up to do in stocking their book databases. But the two efforts may not be in such close competition as it would initially seem.

Google’s library initiative is an extremely bold commercial gambit. If it wins its cases, it stands to make a great deal of money, even after the tens of millions it is spending on the scanning and indexing the billions of pages, off a tiny commodity: the text snippet. But far from being the seed of a new literary remix culture, as Kevin Kelly would have us believe (and John Updike would have us lament), the snippet is simply an advertising hook for a vast ad network. Google’s not the Library of Babel, it’s the most sublimely sophisticated advertising company the world has ever seen (see this funny reflection on “snippet-dangling”). The OCA, on the other hand, is aimed at creating a legitimate online library, where books are not a means for profit, but an end in themselves.

Brewster Kahle, the founder and leader of the OCA, has a rather immodest aim: “to build the great library.” “That was the goal I set for myself 25 years ago,” he told The San Francisco Chronicle in a profile last year. “It is now technically possible to live up to the dream of the Library of Alexandria.”

So while Google’s venture may be more daring, more outrageous, more exhaustive, more — you name it –, the OCA may, in its slow, cautious, more idealistic way, be building the foundations of something far more important and useful. Plus, Kahle’s got the Bookmobile. How can you not love the Bookmobile?

wikipedia lampooned in onion

The Onion takes a shot at Wikipedia this week:

Wikipedia, the online, reader-edited encyclopedia, honored the 750th anniversary of American independence on July 25 with a special featured section on its main page Tuesday.

Not bad, though it kinda beats the Wikipedia-is-error-prone point into the ground. But the fact that it’s being satirized says something.

Naturally, the piece has already been noted on Wikipedia’s article on The Onion. The talk page points to another, funnier, wiki-themed “news brief” from last September: “Congress Abandons WikiConstitution.”

today at noon (e.s.t.)! online colloquy at chronicle of higher ed.

Bob will be appearing online at the Chronicle of Higher Education site for a live chat with readers about our recent cover story. The topic: “conversational scholarship.” 12 noon E.S.T.

UPDATE: you can now read a transcript of the chat here (same as the live link).

ebook ipod rumored

Engadget has it from inside sources at Apple that a next-generation iPod is in the works with a larger screen and a full-fledged text reader:

Engadget has it from inside sources at Apple that a next-generation iPod is in the works with a larger screen and a full-fledged text reader:

…two bits from separate, trustworthy insiders that Apple’s not satisfied merely vending Audible‘s books-on-digital-audio solution. With the iRex iLiad and Sony PRS-500 Portable Reader both right around the corner, is it possible the next iPod might catch the eBook bug? We’d say the possibility is very real, since according to a source at a major publishing house, they were just ordered to archive all their manuscripts — every single one — and send them over to Apple’s Cupertino HQ.

So Audible, huh? Interesting. They got a toehold in the market with audiobooks, and may now be making the transition to ebooks.

A separate trusted source let us know that the next iPod will have a substantial amount of screen real estate (as we’d all suspected), as well as a book reading mode that pumps up the contrast and drops into monochrome for easy reading. It’s no e-ink, sure, but a widescreen iPod would be well suited for the purpose, and according to our source, the books you’d buy (presumably through iTunes) won’t have an expiration…

I’d hope that such a device would have wifi, a web browser and an RSS reader that could be taken offline. I think that books will only be a part of the equation.

Teleread has the ebook standards angle.