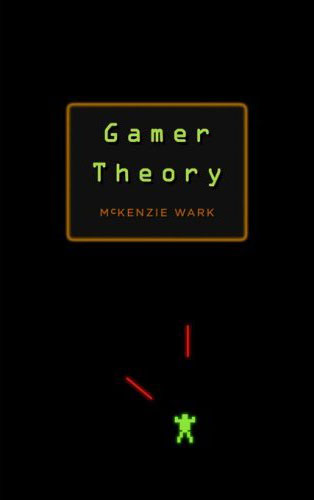

Back in July, we announced plans to build MediaCommons, a new kind of scholarly press for the digital age with a focus on media studies — a wide-ranging network that will weave together various forms of online discourse into a comprehensive publishing environment. At its core, MediaCommons will be a social networking site where academics, students, and other interested members of the public can write and critically converse about a mediated world, in a mediated environment. We’re trying to bridge a number of communities here, connecting scholars, producers, lobbyists, activists, critics, fans, and consumers in a wide-ranging, critically engaged conversation that is highly visible to the public. At the same time, MediaCommons will be a full-fledged electronic press dedicated to the development of born-digital scholarship: multimedia “papers,” journals, Gamer Theory-style monographs, and many other genre-busting forms yet to be invented.

Today we are pleased to announce the first concrete step toward the establishment of this network: making MediaCommons, a planning site through which founding editors Avi Santo (Old Dominion U.) and Kathleen Fitzpatrick (Pomona College) will lead a public discussion on the possible directions this all might take.

The site presently consists of three simple sections:

1) A weblog where Avi and Kathleen will think out loud and work with the emerging community to develop the full MediaCommons vision.

2) A call for “papers” — scholarly projects that engagingly explore some aspect of media history, theory, or culture through an adventurous use of the broad palette of technologies provided by the digital network. These will be the first round of texts published by MediaCommons at the time of its launch.

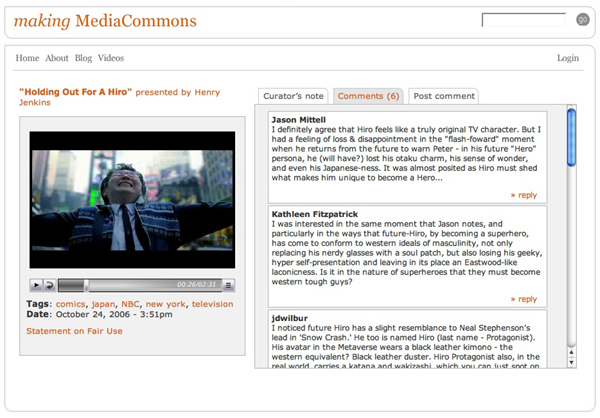

3) In Media Res — an experimental feature where each week a different scholar will present a short contemporary media clip accompanied by a 100-150 word commentary, alongside which a community discussion can take place. Sort of a “YouTube” for scholars and a critically engaged public, In Media Res is presented as just one of the many possible kinds of collaborative, multi-modal publications that MediaCommons could eventually host. With this feature, we are also making a stand on “fair use,” asserting the right to quote from the media for scholarly, critical and pedagogical purposes. Currently on the site, you’ll find videos curated by Henry Jenkins of MIT, Jason Mittell of Middlebury College and Horace Newcomb of the University of Georgia (and the founder of the Peabody Awards). There’s an open invitation for more curators.

Other features and sections will be added over time and out of this site the real MediaCommons will eventually emerge. How exactly this will happen, and how quickly, is yet to be seen and depends largely on the feedback and contributions from the community that will develop on making MediaCommons. We imagine it could launch as early as this coming Spring or as late as next Fall. Come take a look!