“Pretty much Google is trying to set themselves up as the only place to get to these materials; the only library; the only access. The idea of having only one company control the library of human knowledge is a nightmare.”

From a video interview with Elektrischer Reporter (click image to view).

(via Google Blogoscoped)

Author Archives: ben vershbow

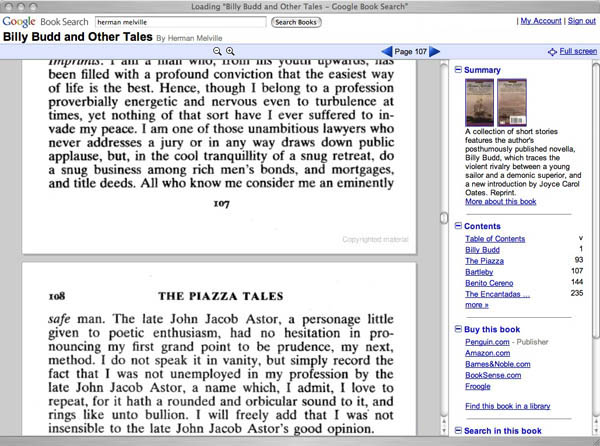

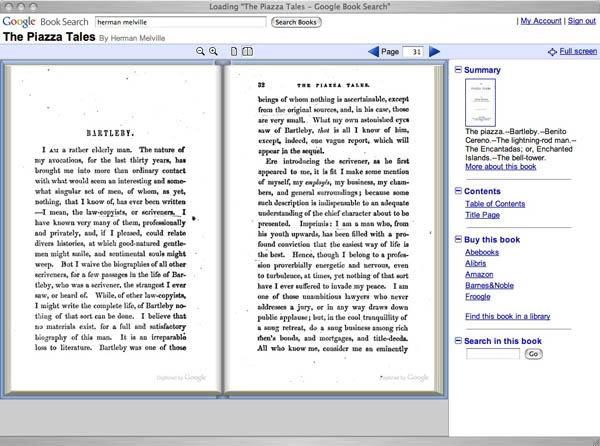

google makes slight improvements to book search interface

Google has added a few interface niceties to its Book Search book viewer. It now loads multiple pages at a time, giving readers the option of either scrolling down or paging through left to right. There’s also a full screen reading mode and a “more about this book” link taking you to a profile page with links to related titles plus references and citations from other books or from articles in Google Scholar. Also on the profile page is a searchable keyword cluster of high-incidence names or terms from the text.

Above is the in-copyright Signet Classic edition of Billy Budd and Other Tales by Melville, which contains only a limited preview of the text. You can also view the entire original 1856 edition of Piazza Tales as scanned from the Stanford Library. Public domain editions like this one can now be viewed with facing pages.

Still a conspicuous lack of any annotation or social reading tools.

dutch fund audiovisual heritage to the tune of 173 million euros

Larry Lessig writes in Free Culture:

Why is it that the part of our culture that is recorded in newspapers remains perpetually accessible, while the part that is recorded on videotape is not? How is it that we’ve created a world where researchers trying to understand the effect of media on nineteenth-century America will have an easier time than researchers trying to understand the effect of media on twentieth-century America?

Twentieth century Holland, it turns out, will be easier to decipher:

The Netherlands Government announced in its annual budget proposal the support for the project “Images for the Future” (in Dutch). Images for the Future is a large-scale conservation and digitalisation operation comprising 285,000 hours of film, television and radio recordings, and 2.9 million photos. The investment of 173 million euro, is spread over a period of seven years.

…It is unprecedented in its scale and ambition. All these films, programmes and photos will be made available for educational and creative purposes. An infrastructure for digital distribution will also be developed. A basic collection will be made available without copyright or under a Creative Commons licence. Making this heritage digitally available will lead to innovative applications in the area of new media and the development of valuable services for the public. The income/expense analysis included in the project plan shows that on balance the project will produce a positive social effect in the Dutch economy to the value of 20 to 60 million euros.

— from Association of Moving Image Archivists list-server

Pretty inspiring stuff.

Eddie Izzard once described the Netherlandish brand of enlightenment in a nutshell: “The Dutch speak four languages and smoke marijuana!” We now see that they also deem it wise policy to support a comprehensive cultural infrastructure for the 21st century, enabling their citizens to read, quote and reuse the media that shapes their world (while they whiz around on bicycles over tidy networks of canals). Not so here in the States where the government works for the monopolies, keeping big media on the dole through Sonny Bono-style protectionism. We should pass our benighted politicos a little of what the Dutch are smoking.

laurels

We recently learned that the Institute has been honored in the Charleston Advisor‘s sixth annual Readers Choice Awards. The Advisor is a small but influential review of web technologies run by a highly respected coterie of librarians and information professionals, who also hold an important annual conference in (you guessed it) Charleston, South Carolina. We’ve been chosen for our work on the networked book:

The Institute for the Future of the Book is providing a creative new paradigm for monographic production as books move from print to the screen. This includes integration of multimedia, interviews with authors and inviting readers to comment on draft manuscripts.

A special award also went to Peter Suber for his tireless service on the Open Access News blog and the SPARC Open Access Forum. We’re grateful for this recognition, and to have been mentioned in such good company.

book as terrain

People have done all sorts of interesting things with Google maps, but this one I particularly like. Maplib lets you upload any image (the larger and higher res the better) into the Google map interface, turning the picture into a draggable, zoomable and annotatable terrain — a crude mashup tool that nonetheless suggests new spacial ways of navigating text.

I did a quick and dirty image mapping of W.H. Auden’s “Musee des Beaux Arts” onto Breughel’s “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus,” casting the shepherd as poet. Click the markers and then the details links to read the poem (hint: start with the shepherd).

As you can see, they give you the code to embed image maps on other sites. You can post comments on the individual markers right here on if:book, or if you go to the Maplib site itself you can add your own markers.

I quite like this one that someone uploaded of a southerly view of the Italian peninsula (unfortunately it seems to start larger images off-center):

And here’s an annotated Korean barbecue (yum):

mckenzie wark on creative commons

Ken Wark is a “featured commoner” on the Creative Commons Text site in recognition of GAM3R 7H30RY, which is published under a CC Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 license. They’ve posted an excellent interview with Ken where he reflects on writing at the intersection of print and web and on the relationship between gift and commodity economies in the realm of ideas. Great stuff. Highly recommended.

Ken also traces some of the less-known prehistory of the Creative Commons movement:

…one of my all time favorite books is Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle. There’s a lovely edition for sale from Zone Books. Today its Amazon rank is about 18,000 – but I’ve seen it as high as 5,000. This edition has been in print for twelve years.

You can also get the whole text free online. In fact there are three whole translations you can download. In the ’60s Debord was editor of a journal called Internationale Situationiste. All of it is freely available now in translation.

The Situationists were pioneers in alternative licensing. The only problem was they didn’t have access to a good license that would allow noncommercial circulation but also bar unauthorized commercial exploitation. There were some terrible pirate editions of their stuff. Their solution to a bad Italian commercial edition was to go to the publisher and trash their office. There has to be a better way of doing things than that.

But in short: the moral of the story is that if you give a nice enough gift to potential readers, they return the gift by buying your stuff. Debord’s works are now classics. Constantly reprinted, a nice little earner for his widow. But it is because of this huge gift of stuff to readers that readers – generations of them – return the favor by buying the works.

Culture has always worked like that. The real question to ask is the reverse: how is anyone except the media conglomerates going to make a living when they have commodified culture to within an inch of its life? How are they even going to make a living off it? It’s never been done before in the history of the world.

The interview was actually done several months ago, before Ken had inked his deal with Harvard University Press, so a few sections regarding future prospects of the book are dated.

the ethics of web applications

Eddie Tejeda, a talented web developer based here in Brooklyn who has been working with us of late, has a thought-provoking post on the need for a new software licensing paradigm for web-based applications:

When open source licenses were developed, we thought of software as something that processed local and isolated data, or sometimes data in a limited network. The ability to access or process that data depended on the ability to have the software installed on your machine.

Now more and more software is moving from local machines to the web, and with it an ever-increasing stockpile of our personal data and intellectual property (think webmail, free blog hosting like Blogger, MySpace and other social networking sites, and media-sharing sites like Flickr or YouTube). The question becomes: if software is no longer a tool that you install but rather a place to which you upload yourself, how is your self going to be protected? What should be the rules of this game?

from weblog to prologue

Over on Without Gods, Mitch Stephens has just posted a draft of his book’s prologue. Readers can download the file and then post feedback on the blog.

wiki book on networked business

Form will follow content in We Are Smarter Than Me, a book on social networks and business written by… a social network of business professors, students and professionals — on a wiki. They’re calling it a “network book”:

The central premise of We Are Smarter Than Me is that large groups of people (“We”) can, and should, take responsibility for traditional business functions that are currently performed by companies, industries and experts (“Me”).

[…]

A few books have recently been written on this topic, but they all fail to confront one central paradox. While they extol the power of communities, they were each written by only one person. We’re putting this paradox to the test by inviting hundreds of thousands of authors to contribute to this “network book” using today’s technologies.

The project is a collaboration between Wharton Business School, MIT Sloan School of Management and a company called Shared Insights. A print book will be published by Pearson in Fall ’07. The site reveals little about how the writing process will be organized, but it’s theoretically open to anyone. As of this writing, I see 983 members.

To get a sense of some of the legal strings that could enwrap future networked publishing deals, take a look at the terms of service for participating authors. You sign away most rights to your contributions, though you’re free to reproduce or rework them non-commercially under a CC license. All proceeds of the book will be given to a charity of the community’s collective choosing. And here’s an interesting new definition of the publisher: “community manager” and “provider of venues for interaction.”

a dictionary in transition

James Gleick had a fascinating piece in the Times Sunday magazine on how the Oxford English Dictionary is reinventing itself in the digital age. The O.E.D. has always had to keep up with a rapidly evolving English language. It took over 60 years and two major supplements to arrive at a second edition in 1989, around the same time Tim Berners-Lee and others at the CERN particle physics lab in Switzerland were creating up with the world wide web. Ever since then, the O.E.D. been hard at work on a third edition but under radically different conditions. Now not only the language but the forms in which the language is transmitted are in an extreme state of flux:

In its early days, the O.E.D. found words almost exclusively in books; it was a record of the formal written language. No longer. The language upon which the lexicographers eavesdrop is larger, wilder and more amorphous; it is a great, swirling, expanding cloud of messaging and speech: newspapers, magazines, pamphlets; menus and business memos; Internet news groups and chat-room conversations; and television and radio broadcasts.

Crucial to this massive language research program is a vast alphabet soup known as the Oxford English Corpus, a growing database of more than a billion words, culled mostly from the web, which O.E.D. lexicographers analyze through various programs that compare and contrast contemporary word usages in contexts ranging from novels and academic papers to teen chat rooms and fan sites. Together this data comprises what the O.E.D. calls “the fullest, most accurate picture of the language today” (I’m curious to know how broadly they survey the world’s general adoption of English. I’m under the impression that it’s still largely an Anglo-American affair).

Marshall McLuhan famously summarized the shift from oral tradition to the written word as “an eye for an ear”: a general migration of thought and expression away from the folkloric soundscapes of tribal society toward encounters by individuals with visual symbols on a page, a movement that climaxed in the age of print, and which McLuhan saw at last reversed in the global village of electronic mass media. The curious thing that McLuhan did not live long enough to witness was the fusion of eye-ear cultures in the fast-moving textual traditions of cell phones and the Internet. Written language has acquired an immediacy and a malleability almost matching oral speech, and the effect is a disorienting blurring of boundaries where writing is almost the same as speaking, reading more like overhearing.

So what is a dictionary to do? Or be? Such fundamental change in the process of maintaining “the definitive record of the English language” must have an effect on the product. Might the third “edition” be its final never-ending one? Gleick again:

No one can say for sure whether O.E.D.3 will ever be published in paper and ink. By the point of decision, not before 20 years or so, it will have doubled in size yet again. In the meantime, it is materializing before the world’s eyes, bit by bit, online. It is a thoroughgoing revision of the entire text. Whereas the second edition just added new words and new usages to the original entries, the current project is researching and revising from scratch — preserving the history but aiming at a more coherent whole.

They’ve even experimented with bringing readers into the process, working with the BBC earlier this year to solicit public aid in locating first usages for a list of particularly hard-to-trace words. One wonders how far they’d go in this direction. It’s one thing to let people contribute at the edges — the 50 words in that list are all from the 20th century — but to open the full source code is quite another. It seems the dictionary’s challenge is to remain a sturdy ark for the English language during this period of flood, and to proceed under the assumption that we may have seen the last of the land.

(image by Kenneth Moyle)