Interesting bit of media industry theater here. I’m here in the New York Public Library, one of the city’s great temples to the book, where Google has assembled representatives of the book business to undergo a kind of group massage. A pep talk for a timorous publishing industry that has only barely dipped its toes in the digital marketplace and can’t decide whether to regard Google as savior or executioner. The speaker roster is a mix of leading academic and trade publishers and diplomatic envoys from the techno-elite. Chris Anderson, Cory Doctorow, Seth Godin, Tim O’Reilly have all spoken. The 800lb. elephant in the room is of course the lawsuits brought against Google (still in the discovery phase) by the Association of American Publishers and the Authors’ Guild for their library digitization program. Doctorow and O’Reilly broached it briefly and you could feel the pulse in the room quicken. Doctorow: “We’re a cabal come over from the west coast to tell you you’re all wrong!” A ripple of laughter, acid-laced. A little while ago Michael Holdsworth of Cambridge University Press pointed to statistics that suggest that Book Search is driving up their sales… Some grumble that the publishers’ panel was a little too hand-picked.

Google’s tactic here seems simultaneously to be to reassure the publishers while instilling an undercurrent of fear. Reassure them that releasing more of their books in a greater variety of forms will lead to more sales (true) — and frightening them that the technological train is speeding off without them (also true, though I say that without the ecstatic determinism of the Google folks. Jim Gerber, Google’s main liason to the publishing world, opened the conference with a love song to Moore’s Law and the gigapixel camera, explaining that we’re within a couple decades’ reach of having a handheld device that can store all the content ever produced in human history — as if this fact alone should drive the future of publishing). The event feels more like a workshop in web marketing than a serious discussion about the future of publishing. It’s hard to swallow all the marketing speak: “maximizing digital content capabilities,” “consolidation by market niche”; a lot of talk of “users” and “consumers,” but not a whole lot about readers. Publishers certainly have a lot of catching up to do in the area of online commerce, but barely anyone here is engaging with the bigger questions of what it means to be a publisher in the network era. O’Reilly sums up the publisher’s role as “spreading the knowledge of innovators.” This is more interesting and O’Reilly is undoubtedly doing more than almost any commercial publisher to rethink the reading experience. But most of the discussion here is about a culture industry that seems more concerned with salvaging the industry part of itself than with honestly rethinking the cultural part. The last speaker just wrapped up and it’s cocktail time. More thoughts tomorrow.

Author Archives: ben vershbow

bush’s iraq speech: a critical edition

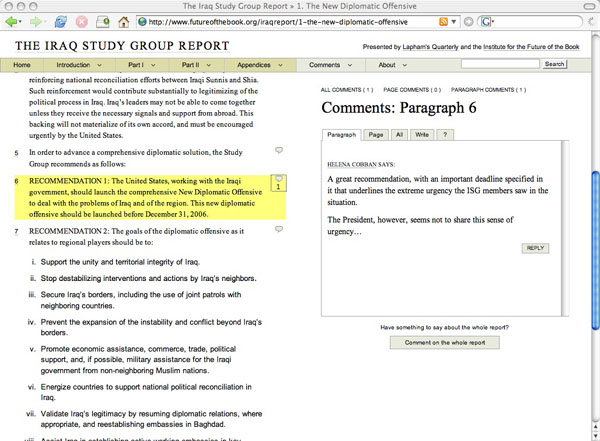

Last month we published an online edition of the Iraq Study Group Report in a new format we’re developing (in-house name is “Comment Press”) that allows readers to enter into conversation with a text and with one another. This was a first step in a creative partnership with Lewis Lapham and Lapham’s Quarterly, a new journal that will look at contemporary issues through the lens of history. Launching only a few days before Christmas, the timing was certainly against us. Only a handful of commenters showed up in those first few days, slowing down almost to a halt as the holiday hibernation period set in. Since New Year’s, however, the site has been picking up momentum and has now amassed a sizable batch of commentary on the Report from a diverse group of respondents including Howard Zinn, Frances FitzGerald and Gary Hart.

While that discussion continues to develop in the Report’s margins, we are following it up with a companion text: the transcript and video of President Bush’s address to the nation last night where he outlined his new strategy for Iraq, presented in a similarly Talmudic fashion with commentary accreting around the central text. To these two documents invited readers and other interested members of the public can continue to append their comments, criticisms and clarifications, “at liberty to find,” in Lapham’s words, “‘the way forward’ in or out of Iraq, back to the future or across the Potomac and into the trees.”

An added feature this time around is that we’re opening the door to general commenters, although with a fairly high barrier to entry. This is an experiment with a more rigorously moderated kind of web discussion and a chance for Lapham and his staff to begin to explore what it means to be editors in the network environment. Anyone is welcome to apply for entry into the discussion by providing a little background on themselves and a sample first comment. If approved by the Lapham’s Quarterly editors (this will all happen within the same day), they will be given a login, at which point they can fire at will on both the speech and the report.

Together these two publications comprise Operation Iraqi Quagmire, a journalistic experiment and a gesture toward a new way of handling public documents in a networked democracy.

***Note: we strongly recommend viewing this on Firefox***

blogging restructures consciousness?

The following story suggests that it does. Last month, Chris Bowers of the progressive political blog MyDD, underwent a small existential crisis brought on by a ham-fisted report on public television about political blogging that bungled a number of basic facts, including Bowers’ very existence on the MyDD masthead. The result was a rare moment of introspection in an otherwise hyper-extroverted medium:

…I admit that the past three years of blogging have altered me in some rather dramatic ways that do, in fact, begin to call very existence into question. I am not referring to the ways that blogging has caused a career change, granted me political and media access that I still find shocking, almost entirely ended my participation in old social circles and presented me with new ones, allowed me to work from home, or otherwise had an impact on the day to day activities of my life. Instead, I am actually referring to an important way in which blogging has altered my very consciousness. After two and a half years of virtually non-stop blogging, my perception of myself as a distinct individual has dramatically waned. My interior monologue has virtually disappeared. I no longer have aesthetic-based epiphanies, and I almost never concern myself with examining internal passions or emotions anymore. Blogging has not just changed the activities in which I engage–the activities in which I engage in order to be a successful blogger have profoundly altered the way my mind operates and the way I conceptualize my agency in relation to others. In effect, I do not exist in the same way I once existed.

First off, I’m reminded of something Sebastian Mary was saying last month about moving beyond the idea of “authorship” and the economic and political models that undergird it (the print publishing industry, academia etc.) toward genuinely new forms of writing for the electronic landscape. “My hunch,” she says, “is that things are going two ways: writers as orchestrators of mass creativity, or writers as wielders of a new rhetoric.” Little is understood about what the collapse of today’s publishing systems would actually mean or look like, and even less about the actual experience of the new writing — that is, the new states of mind and modes of vision that are only beginning to be cracked open through the exploration of new forms. Bowers, as a spokesman for the new rhetoric (or at least one fledgeling branch of it) shines a small light on this murky area.

This also brings me back to Bob’s recent excursion into Walter Ong territory, talking about the possibility of a shift, through new networked forms of creativity, back toward something resembling the collectivity of oral cultures. Bowers and his blog might suggest the beginnings of a case study. Is this muting of the interior monologue, this waning sense of self as a “distinct individual,” the product of a kind of communication that is at once written and oral — both individualistic and collective?

This also brings me back to Bob’s recent excursion into Walter Ong territory, talking about the possibility of a shift, through new networked forms of creativity, back toward something resembling the collectivity of oral cultures. Bowers and his blog might suggest the beginnings of a case study. Is this muting of the interior monologue, this waning sense of self as a “distinct individual,” the product of a kind of communication that is at once written and oral — both individualistic and collective?

Ong called the invention of writing the “technologizing of the word,” a process that fundamentally restructures human consciousness. In this history of literacy, the spoken word is something that wells up directly from the human unconscious, whereas written language is expressed through artificial (i.e. human-made) frameworks, systems of “consciously contrived, articulable rules.” These rules (and their runes) create a scaffold for the brain, which, now able to engage with complex ideas in contemplative solitude as opposed to interlocution, begins to conceive of itself as an individual entity rather than as part of a collective. Literate cultures are thus cognitively different than oral ones.

Bowers’ confession suggests that this progression is being, if not reversed, then at least confused.

The kind of communication that he and his fellow rhetoriticians have been orchestrating in recent years in the blogosphere — not to mention parallel developments elsewhere with wikis, message boards, social media, games and other inchoate forms that feel as much like public spaces as documents — has a speed and plasticity that approaches oral communication. A blog post isn’t so much a finished opus as a lump of clay that readers and other bloggers collectively shape through comments and discussion. Are these new technologies of the word (and beyond the word) restructuring consciousness?

Bowers concludes:

We political bloggers have spilled a great deal of ink on analytical, meta-blogosphere commentaries, and on how we would like to se the political process be reformed. I think we can do an equally great service–both to politics and to blogging–by spilling a little more ink on ourselves.

has google already won?

Rich Skrenta, an influential computer industry insider, currently co-founder and CEO of Topix.net and formerly a big player at Netscape, thinks it has, crowning Google king of the “third age of computing” (IBM and Microsoft being the first and second). Just the other day, there was a bit of discussion here about whether Google is becoming a bona fide monopoly — not only by dint of its unrivaled search and advertising network, but through the expanding cloud of services that manage our various personal communication and information needs. Skrenta backs up my concern (though he mainly seems awed and impressed) that with time, reliance on these services (not just by individuals but by businesses and oranizations of all sizes) could become so total that there will effectively be no other choice:

Just as Microsoft used their platform monopoly to push into vertical apps, expect Google to continue to push into lucrative destination verticals — shopping searches, finance, photos, mail, social media, etc. They are being haphazard about this now but will likely refine their thinking and execution over time. It’s actually not inconceivable that they could eventually own all of the destination page views too. Crazy as it sounds, it’s conceivable that they could actually end up owning the entire net, or most of what counts.

The meteoric ascendance of the Google brand — synonymous in the public mind with best, quickest, smartest — and the huge advantage the company has gained by becoming “the start page for the Internet,” means that its continued dominance is all but assured. “Google is the environment.” Others here think these predictions are overblown. To me they sound frighteningly plausible.

the ambiguity of net neutrality

The Times comes out once again in support of network neutrality, with hopes that the soon to be Democrat-controlled Congress will make decisive progress on that front in the coming year.

Meanwhile in a recent Wired column, Larry Lessig, also strongly in favor of net neutrality but at the same time hesitant about the robust government regulation it entails, does a bit of soul-searching about the landmark antitrust suit brought against Microsoft almost ten years ago. Then too he came down on the side of the regulators, but reflecting on it now he says might have counseled differently had he known about the potential of open source (i.e. Linux) to rival the corporate goliath. He worries that a decade from now he may arrive at similar regrets when alternative network strategies like community or municipal broadband may by then have emerged as credible competition to the telecoms and telcos. Still, seeing at present no “Linus Torvalds of broadband,” he decides to stick with regulation.

Network neutrality shouldn’t be trumpeted uncritically, and it’s healthy and right for leading advocates like Lessig to air their concerns. But I think he goes too far in saying he was flat-out wrong about Microsoft in the late 90s. Even with the remarkable success of Linux, Microsoft’s hegemony across personal and office desktops seems more or less unshaken a decade after the DOJ intervened.

Allow me to add another wrinkle. What probably poses a far greater threat to Microsoft than Linux is the prospect of a web-based operating system of the kind that Google is becoming, a development that can only be hastened by the preservation of net neutrality since it lets Google continue to claim an outsized portion of last-mile bandwidth at a bargain rate, allowing them to grow and prosper all the more rapidly. What seems like an obvious good to most reasonable people might end up opening the door wider for the next Microsoft. This is not an argument against net neutrality, simply a consideration of the complexity of getting what we wish and fight for. Even if we win, there will be other fights ahead. United States vs. Google?

retreat to his study / thoughts for ’07

2006 was a big year for the Institute. We emerged as a sort of publishing lab, a place for authors and readers to rethink books in the digital age — both theoretically (in the wide-ranging dicussions on this blog) and practically (in hands-on experimentation). The project that got things rolling on the practical end — and which is now wrapping up its current phase and down-shifting tempo — was undoubtedly Mitch Stephens’ book blog Without Gods. Like many of our experiments, this one emerged not by some grand design but through an offhand suggestion, when we thought we were headed somewhere else.

Two Novembers ago Bob and I were meeting Mitch for lunch at a cafe near NYU to chat about blogging and its impact on the news media (remember that Mitch, though lately preoccupied with the history of atheism, is a professor in the journalism program at NYU). We were preparing to host a meeting at USC of leading academic bloggers to discuss how scholars were beginning to use blogs to enliven discourse in their fields, and how certain ones (like Juan Cole and PZ Myers) were reaching a general readership, bringing their knowledge to bear on media coverage of subjects like Iraq or the intelligent design movement.

At one point during the lunch it came up that Mitch was in the early stages of researching a new book on nonbelievers and the idea was tossed out — I suppose in the spirit of the discussion — that he start a blog to see how the writing process might be opened up in real time, engaging readers in dialog. Mitch seemed intrigued (guardedly) and said he’d think it over.

A few weeks later, back from a fascinating time in LA, I was pleasantly surprised to receive an email from Mitch saying that he’d been considering the blog idea and wanted to give it a shot. We’d returned from the USC meeting pretty charged up by the discussion we had there and convinced that blogging represented at least the primitive beginnings of a major reorganization of scholarly and public discourse. But we were at a loss as to what our small outfit could do to help. Mitch’s email, if not the answer to all our questions, seemed like a great way to get our hands dirty making a tangible product and would perhaps help us to figure out our next steps. We had a few brainstorm meetings, pulled together a basic design, and Without Gods was born.

A year on, I think it’s safe to say that it’s been a success — actually a turning point for us in balancing the proportions in our work of theoretical pondering to practical experimentation. It’s somewhat ironic that the most substantial thing to come out of the academic blogging inquiry was slightly to the side of the initial question, and conceived before the meeting. But that’s often how things occur. Questions lead to other questions. Without Gods led to Gamer Theory, Gamer Theory led to Holy of Holies, which in turn led to the Iraq Study Group Report. Which I suppose all in some way stems from the academic blogging inquiry and the many tributaries it opened up. MediaCommons is steeped in a belief in the importance of vibrant and visible conversation among scholars in forms ranging from the blog to the networked book — values laid out in the original USC gathering, and developed through our work on Without Gods and beyond.

Now, as hinted before, Mitch has decided it’s time to retreat to his study in order to bring the book to fruition — offline. As he forges ahead, however, he’ll carry with him the echoes — and the archive — of the past year’s discussions.

After a year of mostly daily blogging on this site, I am cutting back.

As most of you know, I am writing a book on the history of disbelief for Carroll and Graf. The blog — produced while working on the book — was an experiment conceived by the Institute for the Future of the Book. It has been a success. I have been benefiting from informed and insightful comments by readers of the blog as I’ve tested some ideas from this book and explored some of their connections to contemporary debates.

I may continue to post sporatically here, but now it seems time to retreat to my study to digest what I’ve learned, polish my thoughts and compose the rest of the narrative. The trick will be accomplishing that without losing touch with those – commenters or just silent readers – who are interested in this project….do try to check back here once in a while. There will be some updates and, perhaps, some new experiments.

New experiments such as “Holy of Holies,” a paper that Mitch delivered last month before an NYU working group on “Secularism, Religious Authority, and the Mediation of Knowledge” (it’s still humming with over a hundred comments). Although blog posting will be sporadic, futureofthebook.org/mitchellstephens will remain the internet hub for Mitch’s book, sections of which may appear in draft state in a format similar to the NYU paper (depending on where Mitch, and his publisher, are at). If you’d like to be notified directly of such developments, there’s a form on the site where you can enter your email address.

Thanks, Mitch, and best of luck. We couldn’t have asked for a better partner in exploring this transitional territory. I hope 2007 proves to be as interesting and as healthy a mix of thinking and doing, for you and for us.

scholarpedia: sharpening the wiki for expert results

Eugene M. Izhikevich, a Senior Fellow in Theoretical Neurobiology at The Neurosciences Institute in San Diego, wants to see if academics can collaborate to produce a peer reviewed equivalent to Wikipedia. The attempt is Scholarpedia, a free peer reviewed encyclopedia, entirely open to public contributions but with editorial oversight by experts.

At first, this sounded to me a lot like Larry Sanger’s Citizendium project, which will attempt to add an expert review layer to material already generated by Wikipedia (they’re calling it a “progressive fork” off of the Wikipedia corpus). Sanger insists that even with this added layer of control the open spirit of Wikipedia will live on in Citizendium while producing a more rigorous and authoritative encyclopedia.

At first, this sounded to me a lot like Larry Sanger’s Citizendium project, which will attempt to add an expert review layer to material already generated by Wikipedia (they’re calling it a “progressive fork” off of the Wikipedia corpus). Sanger insists that even with this added layer of control the open spirit of Wikipedia will live on in Citizendium while producing a more rigorous and authoritative encyclopedia.

It’s always struck me more as a simplistic fantasy of ivory tower-common folk détente than any reasoned community-building plan. We’ll see if Walesism and Sangerism can be reconciled in a transcendent whole, or if intellectual class warfare (of the kind that has already broken out on multiple occasions between academics and general contributors on Wikipedia) — or more likely inertia — will be the result.

The eight-month-old Scholarpedia, containing only a few dozen articles and restricted for the time being to three neuroscience sub-fields, already feels like a more plausible proposition, if for no other reason than that it knows who its community is and that it establishes an unambiguous hierarchy of participation. Izhikevich has appointed himself editor-in-chief and solicited full articles from scholarly peers around the world. First the articles receive “in-depth, anonymous peer review” by two fellow authors, or by other reviewers who measure sufficiently high on the “scholar index.” Peer review, it is explained, is employed both “to insure the accuracy and quality of information” but also “to allow authors to list their papers as peer-reviewed in their CVs and resumes” — a marriage of pragmaticism and idealism in Mr. Izhikevich.

After this initial vetting, the article is officially part of the Scholarpedia corpus and is hence open to subsequent revisions and alterations suggested by the community, which must in turn be accepted by the author, or “curator,” of the article. The discussion, or “talk” pages, familiar from Wikipedia are here called “reviews.” So far, however, it doesn’t appear that many of the approved articles have received much of a public work-over since passing muster in the initial review stage. But readers are weighing in (albeit in modest numbers) in the public election process for new curators. I’m very curious to see if this will be treated by the general public as a read-only site, or if genuine collaboration will arise.

It’s doubtful that this more tightly regulated approach could produce a work as immense and varied as Wikipedia, but it’s pretty clear that this isn’t the goal. It’s a smaller, more focused resource that Izhikevich and his curators are after, with an eye toward gradually expanding to embrace all subjects. I wonder, though, if the site wouldn’t be better off keeping its ambitions concentrated, renaming itself something like “Neuropedia” and looking simply to inspire parallel efforts in other fields. One problem of open source knowledge projects is that they’re often too general in scope (Scholarpedia says it all). A federation of specialized encyclopedias, produced by focused communities of scholars both academic and independent — and with some inter-disciplinary porousness — would be a more valuable, if less radical, counterpart to Wikipedia, and more likely to succeed than the Citizendium chimera.

live, on the web, it’s the iraq study group report!

Since leaving Harper’s last spring, Lewis Lapham has been developing plans for a new journal, Lapham’s Quarterly, which will look at important contemporary subjects (one per issue) through the lens of history. Not long ago, Lewis approached the Institute about helping him and his colleagues to develop a web component of the Quarterly, which he imagined as a kind of unorthodox news site where history and source documents would serve as a decoder ring for current events — a trading post of ideas, facts, and historical parallels where readers would play a significant role in piecing together the big picture. To begin probing some of the possibilities for this collaboration, we came up with an exciting and timely experiment: we’ve taken the granular commenting format that we hacked together just a few weeks ago for Mitch Stephens’ paper and plugged in the Iraq Study Group Report. The Lapham crew, for their part, have taken their first editorial plunge into the web, using their broad print network to assemble an astonishing roster of intellectual heavyweights to collectively annotate the text, paragraph by paragraph, live on the site. Here’s more from Lewis:

As expected and in line with standard government practice, the report issued by the Iraq Study Group on December 6th comes to us written in a language that guards against the crime of meaning–a document meant to be admired as a praise-worthy gesture rather than understood as a clear statement of purpose or an intelligible rendition of the facts. How then to read the message in the bottle or the handwriting on the wall?

Lapham’s Quarterly and the Institute for the Future of the Book answers the question with a new form of discussion and critique– an annotated edition of the ISG Report on a website programmed to that specific purpose, evolving over the course of the next three weeks into a collaborative illumination of an otherwise black hole. What you have before you is the humble beginnings of that effort–the first few marginal notes and commentaries furnished by what will eventually be a large number of informed sources both foreign and domestic (historians, military officers, politicians, intelligence operatives, diplomats, some journalists), invited to amend, correct, augment or contradict any point in the text seemingly in need of further clarification or forthright translation into plain English.

As the discussion adds to the number of its participants so also it will extend the reach of its memory and enlarge its spheres of reference. What we hope will take shape on short notice and in real time is the publication of a report that should prove to be a good deal more instructive than the one distributed to the members of Congress and the major news media.

Being at the very beginning of the experiment, what you’ll see on the site today is more or less a blank slate. Our hope is that in the days and weeks ahead, a lively conversation will begin to bubble up in the pages of the report — a kind of collaborative marginalia on a grand scale — mounting toward Bush’s big Iraq strategy speech next month. Around that time, the Lapham’s editors will open up commenting to the public. Until then, here are just some of the people we expect to participate: Anthony Arnove, Helena Cobban, Joshua Cohen, Jean Daniel, Raghida Dergham, Joan Didion, Mark Danner, Barbara Ehrenrich, Daniel Ellsberg, Tom Engelhardt, Stanley Fish, Robert Fisk, Eric Foner, Christopher Hitchens, Rashid Khalidi, Chalmers Johnson, Donald Kagan, Kanan Makiya, William Polk, Walter Russel Mead, Karl Meyer, Ralph Nader, Gianni Riotta, M.J. Rosenberg, Gary Sick, Matthew Stevenson, Frances Stonor, Lally Weymouth, and Wayne White.

Not too shabby.

The form is still very much in the R&D phase, but we’ve made significant improvements since the last round. Add this to your holiday reading stack and watch how it develops.

(We strongly recommend viewing the site in Firefox.)

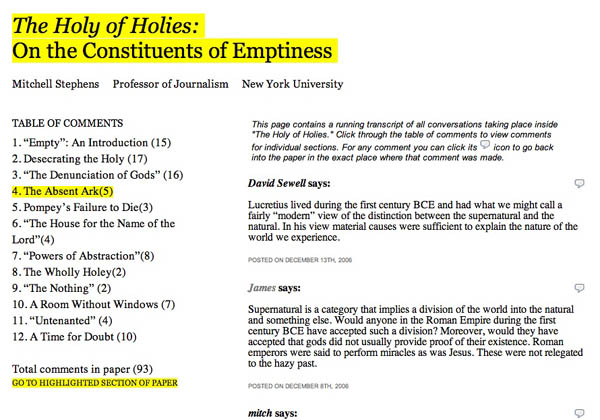

table of comments

Yesterday Bud Parr made the following suggestion regarding the design of Mitch Stephens’ networked paper, “The Holy of Holies”:

I think the site would benefit from something right up front highlighting the most recent exchange of comments and/or what’s getting the most attention in terms of comments.

It just so happens that we’ve been cooking up something that does more or less what he describes: a simple meta comment page, or “table of comments,” displaying a running transcript of all the conversations in the site filtered by section. You can get to it from a link on the front page next to the total comment count for the paper (as of this writing there are 93).

It’s an interesting way to get into the text: through what people are saying about it. Any other ideas of how something like this could work?

report on scholarly cyberinfrastructure

The American Council of Learned Societies has just issued a report, “Our Cultural Commonwealth,” assessing the current state of scholarly cyberinfrastructure in the humanities and social sciences and making a series of recommendations on how it can be strengthened, enlarged and maintained in the future.

The definition of cyberinfastructure they’re working with:

“the layer of information, expertise, standards, policies, tools, and services that are shared broadly across communities of inquiry but developed for specific scholarly purposes: cyberinfrastructure is something more specific than the network itself, but it is something more general than a tool or a resource developed for a particular project, a range of projects, or, even more broadly, for a particular discipline.”

I’ve only had time to skim through it so far, but it all seems pretty solid.

John Holbo pointed me to the link in some musings on scholarly publishing in Crooked Timber, where he also mentions our Holy of Holies networked paper prototype as just one possible form that could come into play in a truly modern cyberinfrastructure. We’ve been getting some nice notices from others active in this area such as Cathy Davidson at HASTAC. There’s obviously a hunger for this stuff.