New York readers save the date!

New York readers save the date!

Next Wednesday the 28th the Institute is hosting the first of what hopes to be a monthly series of new media evenings at Brooklyn’s premier video salon and A/V sandbox, Monkeytown. We’re kicking things off with a retrospective of work by our longtime artist in residence, Alex Itin. February 15th marked the second anniversary of Alex’s site IT IN place, which we’re preparing to relaunch with a spruced up design and a gorgeous new interface to the archives (design of this interface chronicled here and here). We’d love to see you there.

For those of you who don’t know it, Monkeytown is unique among film venues in New York — an intimate rear room with a gigantic screen on each of its four walls, low comfy sofas and fantastic food. A strange and special place. If you think you can come, be sure to make a reservation ASAP as seating will be tight.

More info about the event here.

Author Archives: ben vershbow

an encyclopedia of arguments

I just came across this though apparently it’s been up and running since last summer. Debatepedia is a free, wiki-based encyclopedia where people can collaboratively research and write outlines of arguments on contentious subjects — stem cell reseach, same-sex marriage, how and when to withdraw from Iraq (it appears to be focused in practice if not in policy on US issues) — assembling what are essentially roadmaps to important debates of the moment. Articles are organized in “logic trees,” a two-column layout in which pros and cons, fors and againsts, yeas and neas are placed side by side for each argument and its attendant sub-questions. A fairly strict citations policy ensures that each article also serves as a link repository on its given topic.

This is an intriguing adaptation of the Wikipedia model — an inversion you could say, in that it effectively raises the “talk” pages (discussion areas behind an article) to the fore. Instead of “neutral point of view,” with debates submerged, you have an emphasis on the many-sidedness of things. The problem of course is that Debatepedia’s format suggests that all arguments are binary. The so-called “logic trees” are more like logic switches, flipped on or off, left or right — a crude reduction of what an argument really is.

This is an intriguing adaptation of the Wikipedia model — an inversion you could say, in that it effectively raises the “talk” pages (discussion areas behind an article) to the fore. Instead of “neutral point of view,” with debates submerged, you have an emphasis on the many-sidedness of things. The problem of course is that Debatepedia’s format suggests that all arguments are binary. The so-called “logic trees” are more like logic switches, flipped on or off, left or right — a crude reduction of what an argument really is.

I imagine they used the two column format for simplicity’s sake — to create a consistent and accessible form throughout the site. It’s true that representing the full complexity of a subject on a two-dimensional screen lies well beyond present human capabilities, but still there has to be some way to present a more shaded spectrum of thought — to triangulate multiple perspectives and still make the thing readable and useful (David Weinberger has an inchoate thought along similar lines w/r/t to NPR stories and research projects for listeners — taken up by Doc Searls).

I’m curious to hear what people think. Pros? Cons? Logic tree anyone?

google library dominoes

Princeton is the latest university to partner up with the Google library project, signing an agreement to have 1 million public domain books scanned over the next six years. Over at ALA Techsource Tom Peters voices the growing unease among librarians worried about the long-term implications of commercial enclosure of the world’s leading research libraries.

the future of the times

Here’s a great item from last week that slipped through the cracks… A rare peek into the mind of New York Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger, which grew out of a casual conversation with Haaretz‘s Eytan Avriel at the World Economic Forum in Davos. A couple of choice sections follow…

On moving beyond print:

Given the constant erosion of the printed press, do you see the New York Times still being printed in five years?

“I really don’t know whether we’ll be printing the Times in five years, and you know what? I don’t care either,” he says…..”The Internet is a wonderful place to be, and we’re leading there,” he points out.

The Times, in fact, has doubled its online readership to 1.5 million a day to go along with its 1.1 million subscribers for the print edition.

Sulzberger says the New York Times is on a journey that will conclude the day the company decides to stop printing the paper. That will mark the end of the transition. It’s a long journey, and there will be bumps on the road, says the man at the driving wheel, but he doesn’t see a black void ahead.

On the persistent need for editors — Sulzberger talks about newspapers reinventing themselves as “curators of news”:

In the age of bloggers, what is the future of online newspapers and the profession in general? There are millions of bloggers out there, and if the Times forgets who and what they are, it will lose the war, and rightly so, according to Sulzberger. “We are curators, curators of news. People don’t click onto the New York Times to read blogs. They want reliable news that they can trust,” he says.

“We aren’t ignoring what’s happening. We understand that the newspaper is not the focal point of city life as it was 10 years ago.

“Once upon a time, people had to read the paper to find out what was going on in theater. Today there are hundreds of forums and sites with that information,” he says. “But the paper can integrate material from bloggers and external writers. We need to be part of that community and to have dialogue with the online world.”

belgian news sites don cloak of invisibility

In an act of stunning shortsightedness, a consortium of 19 Belgian newspapers has sued and won a case against Google for copyright infringement in its News Search engine. Google must now remove all links, images and cached pages of these sites from its database or else face fines. Similar lawsuits from other European papers are likely to follow soon.

The main beef in the case (all explained in greater detail here) is Google’s practice of deep linking to specific articles, which bypasses ads on the newspapers’ home pages and reduces revenue. This and Google’s caching of full articles for search purposes, copies that the newspapers contend could be monetized through a pay-for-retrieval service. Echoes of the Book Search lawsuits on this side of the Atlantic…

What the Belgians are in fact doing is rendering their papers invisible to a potentially global audience. Instead of lashing out against what is essentially a free advertising service, why not rethink your own ad structure to account for the fact that more and more readers today are coming through search engines and not your front page? While you’re at it, rethink the whole idea of a front page. Or better yet, join forces with other newspapers, form your own federated search service and beat Google at its own game.

jonathan lethem: the ecstasy of influence

If you haven’t already, check out Jonathan Lethem’s essay in the latest issue of Harper’s on the trouble with copyright. Nothing particularly new to folks here, but worth reading all the same — an elegant meditation by an elegant writer (and a fellow Brooklynite) on the way that all creativity is actually built on appropriation, reuse or all-out theft:

Any text is woven entirely with citations, references, echoes, cultural languages, which cut across it through and through in a vast stereophony. The citations that go to make up a text are anonymous, untraceable, and yet already read; they are quotations without inverted commas. The kernel, the soul–let us go further and say the substance, the bulk, the actual and valuable material of all human utterances–is plagiarism. For substantially all ideas are secondhand, consciously and unconsciously drawn from a million outside sources, and daily used by the garnerer with a pride and satisfaction born of the superstition that he originated them; whereas there is not a rag of originality about them anywhere except the little discoloration they get from his mental and moral caliber and his temperament, and which is revealed in characteristics of phrasing. Old and new make the warp and woof of every moment. There is no thread that is not a twist of these two strands. By necessity, by proclivity, and by delight, we all quote. Neurological study has lately shown that memory, imagination, and consciousness itself is stitched, quilted, pastiched. If we cut-and-paste our selves, might we not forgive it of our artworks?

under the influence

The Wall Street Journal has an interesting (and free) piece on a new class of individuals — filters, recommenders, editors, curators, call them what you will — that is becoming increasingly influential in directing attention traffic across the Web. The article focuses primarily on top link hounds at user-filtered news sites like Digg, Reddit and the newly reborn Netscape, sites whose aggregate tastemaking muscle has caught the attention of marketers and product placers, who have made various efforts to buy influence through elaborate vote-rigging schemes and good old-fashioned payola. The article also makes mention of some notable solo filtering acts including a regular stop of mine, ThrowAwayYourTV.com, a video archive operated by a young Canadian named Jeff Hoard. At the end of the piece there’s a list with links of other important “influencers.”

While I was reading this I kept thinking of Time Magazine’s “The Person of the Year is You”, which caused a minor stir last December with its cover containing a little mirror in a YouTube-like screen. On one level the piece was simple trend-spotting, a comment on the phenomenon (undoubtedly reaching new heights in ’06) of social media production. But it could also be read as a thinly camouflaged corporate memo announcing big media’s awakening to the potentially enormous profits of an ad-based media network in which the users do all the work of filtering. And it’s precisely the sorts of “influencers” in this WSJ piece that are the “you” on which they are hoping to capitalize. The “you” that convinced Google that $1.8 billion was a price worth paying for YouTube, or Rupert Murdoch a half billion for MySpace (I would have liked to have heard more in the article about the way this phenomenon is playing out on these two sites through the video “channels” and friend networks).

It all adds up to a pretty astonishing redefinition of what “the media” is. The front page, the lead story, the primetime lineup — all in constant renegotiation, constantly rearranged. Yet still in so many ways dependent on the established sources for the materials to be filtered (and probably in the future for personal income, as is already beginning). Feeders and filterers. The new media ecology doesn’t destroy the old one, it absorbs it into a new relationship.

a million penguins: a wiki-novelty

You may by now have heard about A Million Penguins, the wiki-novel experiment currently underway at Penguin Books. They’re trying to find out if a self-organizing collective of writers can produce a credible novel on a live website. A dubious idea if you believe a novel is almost by definition the product of a singular inspiration, but praiseworthy nonetheless for its experimental bravado.

Already, they’ve run into trouble. Knowing a thing or two about publicity, Penguin managed to get a huge amount of attention to the site — probably too much — almost immediately. Hundreds of contributors have signed up: mostly earnest, some benignly mischievous, others bent wholly on disruption. I was reminded naturally of the LA Times’ ill-fated “wikitorial” experiment in June of ’05 in which readers were invited to rewrite the paper’s editorials. Within the first few hours, the LAT had its windshield wipers going at full speed and yet still they couldn’t keep up with the shit storm of vandalism that was unleashed — particularly one cyber-hooligan’s repeated posting of the notorious “goatse” image that has haunted many a dream. They canceled the experiment just two days after launch.

Already, they’ve run into trouble. Knowing a thing or two about publicity, Penguin managed to get a huge amount of attention to the site — probably too much — almost immediately. Hundreds of contributors have signed up: mostly earnest, some benignly mischievous, others bent wholly on disruption. I was reminded naturally of the LA Times’ ill-fated “wikitorial” experiment in June of ’05 in which readers were invited to rewrite the paper’s editorials. Within the first few hours, the LAT had its windshield wipers going at full speed and yet still they couldn’t keep up with the shit storm of vandalism that was unleashed — particularly one cyber-hooligan’s repeated posting of the notorious “goatse” image that has haunted many a dream. They canceled the experiment just two days after launch.

All signs indicate that Penguin will not be so easily deterred, though they are making various adjustments to the system as they go. In response to general frustration at the relentless pace of edits, they’re currently trying out a new policy of freezing the wiki for several hours each afternoon in order to create a stable “reading window” to help participants and the Penguin editors who are chronicling the process to get oriented. This seems like a good idea (flexibility is definitely the right editorial MO in a project like this). And unlike the LA Times they seem to have kept the spam and vandalism to within tolerable limits, in part with the help of students in the MA program in creative writing and new media at De Montfort University in Leicester, UK, who are official partners in the project.

When I heard the De Montfort folks would be helping to steer the project I was excited. It’s hard to start a wiki project with no previously established community in the hot glare of a media spotlight . Having a group of experienced writers at the helm, or at least gently nudging the tiller — writers like Kate Pullinger, author of the Inanimate Alice series, who are tapped into the new forms and rhythms of the Net — seemed like a smart move that might lend the project some direction. But digging a bit through the talk pages and revision histories, I’ve found little discernible contribution from De Montfort other than spam cleanup and general housekeeping. A pity not to utilize them more. It would be great to hear their thoughts about all of this on the blog.

So anyway, the novel.

Not surprisingly it’s incoherent. You might get something similar if you took a stack of supermarket checkout lane potboilers and some Mad Libs and threw them in a blender. Far more interesting is the discussion page behind the novel where one can read the valiant efforts of participants to communicate with one another and to instill some semblance of order. Here are the battle wounded from the wiki fray… characters staggering about in search of an author. Writers in search of an editor. One person, obviously dismayed at the narrative’s dogged refusal to make sense, suggests building separate pages devoted exclusively to plotting out story arcs. Another exclaims: “THE STORY AS OF THIS MOMENT IS THE STORY – you are permitted to make slight changes in past, but concentrate on where we are now and move forward.” Another proceeds to forcefully disagree. Others, even more exasperated, propose forking the project into alternative novels and leaving the chaotic front page to the buzzards. How ironic it would be if each user ended up just creating their own page and writing the novel they wanted to write — alone.

Reading through these paratexts, I couldn’t help thinking that this was in fact the real story being written. Might the discussion page contain the seeds of a Tristram Shandyesque tale about a collaborative novel-writing experiment gone horribly awry, in which the much vaunted “novel” exists only in its total inability to be written?

* * * * *

The problem with A Million Penguins in a nutshell is that the concept of a “wiki-novel” is an oxymoron. A novel is probably as un-collaborative a literary form as you can get, while a wiki is inherently collaborative. Wikipedia works because encyclopedias were always in a sense collective works — distillations of collective knowledge — so the wiki was the right tool for reinventing that form. Here that tool is misapplied. Or maybe it’s the scale of participation that is the problem here. Too many penguins. I can see a wiki possibly working for a smaller narrative community.

All of this is not to imply that collaborative fiction is a pipe dream or that no viable new forms have yet been devised. Just read Sebastian Mary’s fascinating survey, published here a couple of weeks back, of emergent net-native literary forms and you’ll see that there’s plenty going on in other channels. In addition to some interesting reflections on YouTube, Mary talks about ARGs, or alternative reality games, a new participatory form in which communities of readers write the story as they go, blending fact and fiction, pulling in multiple media, and employing a range of collaborative tools. Perhaps most pertinent to Penguin’s novel experiment, Mary points out that the ARG typically is not a form in which stories are created out of whole cloth, rather they are patchworks, woven from the rich fragmentary litter of popular culture and the Web:

Participants know that someone is orchestrating a storyline, but that it will not unfold without the active contribution of the decoders, web-surfers, inveterate Googlers and avid readers tracking leads, clues, possible hints and unfolding events through the chaos of the Web. Rather than striving for that uber-modernist concept, ‘originality’, an ARG is predicated on the pre-existence of the rest of the Net, and works like a DJ with the content already present. In this, it has more in common with the magpie techniques of Montaigne (1533-92), or the copious ‘authoritative’ quotations of Chaucer than contemporary notions of the author-as-originator.

Penguin too had the whole wide Web to work with, not to mention the immense body of literature in its own publishing vault, which seems ripe for a remix or a collaborative cut-up session. But instead they chose the form that is probably most resistant to these new social forms of creativity. The result is a well intentioned but confused attempt at innovation. A novelty, yes. But a novel, not quite.

bob on the air

Yesterday Bob did a radio interview on “The Speakeasy” on WFMU, almost certainly the most interesting (and one of the few) independent radio stations in the New York area. I highly recommend giving it a listen. It’s always nice to hear Bob tell the story of the Institute and the decades of work, collaboration and experience that led up to where we are today. Things tend to get caught up in the rhythm of the day to day on the blog so here’s a nice antidote — a big picture moment.

You can get the podcast from the Speakeasy archive in either RealAudio or m3u format (which will play on iTunes or whatever your default media player is on your machine). Heads up: there are a few minutes of jazz music before the interview gets started. The whole thing’s about an hour.

national archives sell out

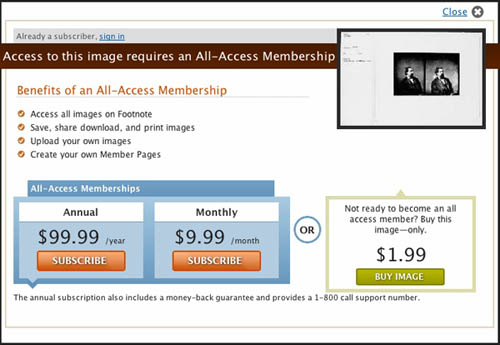

This falls into the category of deeply worrying. In a move reminiscent of last year’s shady Smithsonian-Showtime deal, the U.S. National Archives has signed an agreement with Footnote.com to digitize millions of public domain historical records — stuff ranging from the papers of the Continental Congress to Matthew B. Brady’s Civil War photographs — and to make them available through a commercial website. They say the arrangement is non-exclusive but it’s hard to see how this is anything but a terrible deal.

Here’s a picture of the paywall:

Dan Cohen has a good run-down of why this should set off alarm bells for historians (thanks, Bowerbird, for the tip). Peter Suber has: the open access take: “The new Democratic Congress should look into this problem. It shouldn’t try to undo the Footnote deal, which is better than nothing for readers who can’t get to Washington. But it should try to swing a better deal, perhaps even funding the digitization and OA directly.”

Elsewhere in mergers and acquisitions, the University of Texas Austin is the newest partner in the Google library project.