That’s what Hewlett-Packard is hoping to do. The NYT explains.

HP recently acquired a small online photo-printing company named Tabblo, which has been developing software that will automatically reformat any web page, in any layout, to be easily printable. HP’s goal is to use this technology to create a browser plugin, as ubiquitous as Flash and Java, that could become “the printing engine of the web.” Let’s hope, for the sake of the world’s forests, that a decent electronic reader comes out first.

(Thanks, Peter Brantley.)

Author Archives: ben vershbow

democratization and the networked public sphere

New Yorkers take note! This just came in from Trebor Scholz at the Institute for Distributed Creativity: a terrific-sounding event next Friday evening at The New School. Really wish I could attend but I’ll be doing this in London. Details below.

Democratization and the Networked Public Sphere

* Panel Discussion with dana boyd, Trebor Scholz, and Ethan Zuckerman

Friday, April 13, 2007, 6:30 – 8:30 p.m.

The New School, Theresa Lang Community and Student Center

55 West 13th Street, 2nd floor

New York City

Admission: $8, free for all students, New School faculty, staff, and alumni with valid ID

This evening at the Vera List Center for Art & Politics will discuss the potential of sociable media such as weblogs and social networking sites to democratize society through emerging cultures of broad participation.

danah boyd will argue four points. 1) Networked publics are changing the way public life is organized. 2) Our understandings of public/private are being radically altered 3) Participation in public life is critical to the functioning of democracy. 4) We have destroyed youths’ access to unmediated public life. Why are we now destroying their access to mediated public life? What consequences does this have for democracy?

Trebor Scholz will present the paradox of affective immaterial labor. Content generated by networked publics was the main reason for the fact that the top ten sites on the World Wide Web accounted for most Internet traffic last year. Community is the commodity, worth billions. The very few get even richer building on the backs of the immaterial labor of very very many. Net publics comment, tag, rank, forward, read, subscribe, re-post, link, moderate, remix, share, collaborate, favorite, write. They flirt, work, play, chat, gossip, discuss, learn and by doing so they gain much: the pleasure of creation, knowledge, micro-fame, a “home,” friendships, and dates. They share their life experiences and archive their memories while context-providing businesses get value from their attention, time, and uploaded content. Scholz will argue against this naturalized “factory without walls” and will demand for net publics to control their own contributions.

Ethan Zuckerman will present his work on issues of media and the developing world, especially citizen media, and the technical, legal, speech, and digital divide issues that go alongside it. Starting out with a critique of cyberutopianism, Zuckerman will address citizen media and activism in developing nations, their potential for democratic change, the ways that governments (and sometimes corporations) are pushing back on their ability to democratize.

For more information about the panelists go here.

alex itin netrospectives

Our dear friend and artist in residence Alex Itin has been getting noticed of late. Yesterday he was profiled on The Daily Reel, a popular site that curates quality video from around the web and frequently features his work. Other interesting video sites have also been a-knockin’.

An even better meditation on Alex’s work is this comment posted by Sol Gaitan last month in response to his popular piece, “I Made Pictures of Making a Picture of Everyone Who Might Be Looking At These Pictures of Everyone” (a bona fide blockbuster on Vimeo). I’ve reproduced it in full:

Robert Rauschenberg’s fabulous exhibition of 43 transfer drawings at Jonathan O’Hara Gallery produce that feeling, in retrospective, of seeing something that is going to mean a lot in the future. And they did. Executed in the 60’s they were the precursors, as well as the result, of appropriation. Duchamp and Picasso are two obvious examples that come to mind when one thinks of the origins of appropriation, today we prefer the term “mash-up.” The exciting thing about Rauschenberg is his extraordinary use of the quotidian to create highly manipulated works that elude classification. As his combines include and exclude us, the transfer drawings leave us with a feeling of immediacy and at the same time of blurry memories.

Alex Itin’s play with appropriation produces the same feeling. He is doing something that is going to mean a lot. His investigations of the uses of technology to produce an art as dynamic as its medium, is evident in these “horizontal scrolls.” The medium is limiting, so Alex is searching for a way to blog that defies its verticality, very much along the lines of the Institute, where his art resides. There are extraordinarily beautiful artist homepages on the Internet, but Alex’s redefinition of the blog as a place of encounter, intentional or by chance, a place of fusion where he produces and manipulates his mash-ups is unprecedented. With this “horizontal scroll” he moves a very important step forward. He addresses us in all our anonymity while creating the piece in front of our very individual eyes. His use of the blog as a way of communication through live creation makes it burst along its seams.

The way Rauschenberg’s transfer drawings fall on the paper seems aleatory, but it responds to the limitations he found in both collage and monotype before he started his silkscreen explorations: “I felt I had to find a way to use collage in drawing to incorporate my own way of working on that intimate scale,” (as cited on the show’s catalogue by Lewis Kachur from art historian Roni Feinstein’s dissertation, NYU 1990.) The result are aerial collages of images transferred from newspaper that become a testimony of their times. The 60’s were charged times, and the newsprint chosen by Rauschenberg; the civil rights movement, Vietnam, the invasion of Czechoslovakia, astronauts, consumer products, address high modernism, while their heterogeneity alludes to the fragmentary condition of postmodernism. Alex’s depiction of those looking at his blog is highly charged in a similar manner; who are us anyway? What seems improvisation takes the form of social commentary, as he says on his blog:

who is my audience?… I think I’ll draw them and perform in front of the drawing. Today’s post also asks the question (more than most), which here is the real work of art? The drawing, or the film of the drawing, or the whole thing together on the blog, or what?

Rauschenberg’s masterful use of gouache, watercolor and ink washes lends coherence to the whole. It centers the viewers attention on image and text, fusing them. Their dynamism makes us think of the artist at work. Alex has the medium, and the shrewdness, to put both, process and work, in front of our eyes. The result is not the voyeuristic epiphany of seeing Pollock dripping paint on a canvas that would become the actual piece, here it is the artist at work, moving in precarious terrain, which IS the piece.

Rauschenberg’s pieces elude nomenclature, they are neither painting, nor collage, nor sculpture, they are thresholds to new forms of perception. Today’s challenge is to rethink the meaning of appropriation in a moment when capitalist commodity culture has become the determinant of our daily lives. To appropriate today is to expose the unresolved questions of a world shaped by the information era. Permanence is constantly challenged and the evolution of Alex Itin’s work on his blog shows this as clearly as it can be.

already born digital

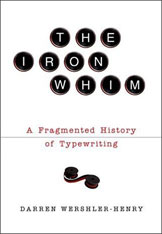

Joan Acocella has an interesting review in The New Yorker of Darren Wershler-Henry’s recent book The Iron Whim: A Fragmented History of Typewriting (previously discussed here on if:book). It’s worth a look just for all the juicy backstory it delivers on the typewriter as well as accounts of various writers’ intense, sometimes haunted, relationships with their machines. But Acocella also delves into an important area that apparently gets only passing consideration in the book — the way writing has changed since the advent of computers. Reading this makes you remember that with word processors we’ve all been writing “born digital” texts for quite some time:

Joan Acocella has an interesting review in The New Yorker of Darren Wershler-Henry’s recent book The Iron Whim: A Fragmented History of Typewriting (previously discussed here on if:book). It’s worth a look just for all the juicy backstory it delivers on the typewriter as well as accounts of various writers’ intense, sometimes haunted, relationships with their machines. But Acocella also delves into an important area that apparently gets only passing consideration in the book — the way writing has changed since the advent of computers. Reading this makes you remember that with word processors we’ve all been writing “born digital” texts for quite some time:

Mallarmé spoke of the uncertainty with which we face a clean sheet of paper and try, in vain, to record our thoughts on it with some precision. As long as we were feeding paper into a typewriter, this anxiety was still present to our minds, and was revealed in the pointillism of Wite-Out, or even in the dapple of letters that were darker, pressed in confidence, as opposed to the lighter ones, pressed more hesitantly. A page produced on a manual typewriter was like a record of the torture of thought. With the P.C., the situation is altogether different. The screen, a kind of indeterminate space, does not seem violable in the same way as the page. And, because what we write on it is so effortlessly and undetectably erasable, the final text buries the evidence of our struggle, asserting that what we said was what we thought all along. Wershler-Henry suggests that the P.C.–with some help from Derrida and Baudrillard–ushered us into a world in which the difference between true and false is no longer cause for doubt or grief; falsity is taken for granted. I don’t know if he was thinking about the spurious perfection of the computer-generated page, but it would be a useful example.

Something else to think about is the effect that the computer, with its astonishing capabilities, has had on us as writers. Take just one example: the ease of moving a block of text. Highlight, hit control X, move cursor, hit control V, and, presto, that paragraph is in a new place. Of course, we were able to move things in typewritten text, too, but all that business with the scissors and the tape made us think twice, and maybe it was wise for us to hesitate before changing the order in which our brains produced our thoughts. In recent years, I have read a lot of writings that seemed to say, “This paragraph is here because it seemed an O.K. place to shove it in.” Furthermore, by allowing us to move text easily, computers influence us to write in movable units. In the novel that won Britain’s Booker Prize last year, Kiran Desai’s “The Inheritance of Loss,” there is a line space, indicating a break of thought, every three pages or so.

dismantling the book

Peter Brantley relates the frustrating experience of trying to hunt down a particular passage in a book and his subsequent painful collision with the cold economic realities of publishing. The story involves a $58 paperback, a moment of outrage, and a venting session with an anonymous friend in publishing. As it happens, the venting turned into some pretty fascinating speculative musing on the future of books, some of which Peter has reproduced on his blog. Well worth a read.

A particularly interesting section (quoted further down) is on the implications for publishers of on-demand disaggregated book content: buying or accessing selected sections of books instead of entire volumes. There are numerous signs that this will be at least one wave of the future in publishing, and should probably prod folks in the business to reevaluate why they publish certain things as books in the first place.

A particularly interesting section (quoted further down) is on the implications for publishers of on-demand disaggregated book content: buying or accessing selected sections of books instead of entire volumes. There are numerous signs that this will be at least one wave of the future in publishing, and should probably prod folks in the business to reevaluate why they publish certain things as books in the first place.

Amazon already provides a by-the-page or by-the-chapter option for certain titles through its “Pages” program. Google presumably will hammer out some deals with publishers and offer a similar service before too long. Peter Osnos’ Caravan Project includes individual chapter downloads and print-on-demand as part of the five-prong distribution standard it is promoting throughout the industry. If this catches on, it will open up a plethora of options for readers but it might also unvravel the very notion of what a book is. Could we be headed for a replay of the mp3’s assault on the album?

The wholeness of the book has to some extent always been illusory, and reading far more fragmentary than we tend to admit. A number of things have clouded our view: the economic imperative to publish whole volumes (it’s more cost-effective to produce good aggregations of content than to publish lots of individual options, or to allow readers to build their own); romantic notions of deep, cover-to-cover reading; and more recently, the guilty conscience of the harried book consumer (when we buy a book we like to think that we’ll read the whole thing, yet our shelves are packed with unfinished adventures).

But think of all the books that you value just for a few particular nuggets, or the books that could have been longish essays but were puffed up and padded to qualify as $24.95 commodities (so many!). Any academic will tell you that it is not only appropriate but vital to a researcher’s survival to hone in on the parts of a book one needs and not waste time on the rest (I’ve received several tutorials from professors and graduate students on the fine art of fileting a monograph). Not all thoughts are book-sized and not all reading goes in a straight line. Selective reading is probably as old as reading itself.

Unbundling the book has the potential to allow various forms of knowledge to find the shapes and sizes that fit them best. And when all the pieces are interconnected in the network, and subject to social discovery tools like tagging, RSS and APIs, readers could begin to assume a role traditionally played by publishers, editors and librarians — the role of piecing things together. Here’s the bit of Peter’s conversation that goes into this:

Peter: …the Google- empowered vision of the “network of books” which is itself partially a romantic, academic notion that might actually be a distinctly net minus for publishers. Potentially great for academics and readers, but potentially deadly for publishers (not to mention librarians). As opposed to the simple first order advantage of having the books discoverable in the first place – but the extent to which books are mined and then inter-connected – that is an interesting and very difficult challenge for publishers.

Am I missing something…?

Friend: If you mean, are book publishers as we know them doomed? Then the answer is “probably yes.” But it isn’t Google’s connecting everything together that’s doing it. If people still want books, all this promotion of discovery will obviously help. But if they want nuggets of information, it won’t. Obviously, a big part of the consumer market that book publishers have owned for 200 years want the nuggets, not a narrative. They’re going, going, gone. The skills of a “publisher” — developing content and connecting it to markets — will have to be applied in different ways.

Peter: I agree that it is not the mechanical act of interconnection that is to blame but the demand side preference for chunks of texts. And the demand is probably extremely high, I agree.

The challenge you describe for publishers – analogous in its own way to that for libraries – is so fundamentally huge as to mystify the mind. In my own library domain, I find it hard to imagine profoundly differently enough to capture a glimpse of this future. We tinker with fabrics and dyes and stitches but have not yet imagined a whole new manner of clothing.

Friend: Well, the aggregation and then parceling out of printed information has evolved since Gutenberg and is now quite sophisticated. Every aspect of how it is organized is pretty much entirely an anachronism. There’s a lot of inertia to preserve current forms: most people aren’t of a frame of mind to start assembling their own reading material and the tools aren’t really there for it anyway.

Peter: They will be there. Arguably, when you look at things like RSS and Yahoo Pipes and things like that – it’s getting closer to what people need.

And really, it is not always about assembling pieces from many different places. I might just want the pieces, not the assemblage. That’s the big difference, it seems to me. That’s what breaks the current picture.

Friend: Yes, but those who DO want an assemblage will be able to create their own. And the other thing I think we’re pointed at, but haven’t arrived at yet, is the ability of any people to simply collect by themselves with whatever they like best in all available media. You like the Civil War? Well, by 2020, you’ll have battle reenactments in virtual reality along with an unlimited number of bios of every character tied to the movies etc. etc. etc. I see a big intellectual change; a balkanization of society along lines of interest. A continuation of the breakdown of the 3-television network (CBS, NBC, ABC) social consensus.

follow the eyes: screenreading reconsidered (again)

From Editor&Publisher (via Print is Dead): The Poynter Institute just released findings from a study in which eye-tracking sensors were used to analyze the behavior of 600 readers across print and online news sources. The resulting data clashes with the usual assumptions:

When readers chose to read an online story, they usually read an average of 77% of the story, compared to 62% in broadsheets and 57% in tabloids…

The study looked at two tabloids, the Rocky Mountain News and Philadelphia Daily News; two broadsheets, the St. Petersburg Times and The Star-Tribune of Minneapolis; and two newspaper Web sites, at the Times and Star-Tribune.

Considering the increasingly disaggregated nature of people’s news-sifting, is “two newspaper websites” really the right test bed for gauging online reading habits? Still, this is a pretty interesting, myth-busting find, though in a way not at all surprising.

This takes us back to the discussion around Cory Doctorow’s recent piece betting on the long-term persistence of print for certain kinds of reading. Print reading, he says, tends toward the sustained and immersive, the long-form linear narrative. Computer reading, on the other hand, is multi-tasky — distracted, social, bite-sized, multidirectional. One could poke a lot of holes in these characterizations, but generally speaking, they do sum up the way in which many of us divide our reading labor (and leisure) across “platforms.” Contrary to popular belief, Doctorow argues, people do like reading on screens. But they also like reading from printed pages. It’s not either/or — the different modes of reading reinforce the different modes of conveyance, paper and PC.

I’ve tended to agree, but many of the folks in the comments here didn’t. They insisted that it’s only a matter of time before we’ll be doing the vast majority of our reading on screens — even the linear, immersive reading that seems most resistant to digital migration. Getting past my own deep attachment to print, and reckoning with how far into daily practice electronic reading has already penetrated in so little time, I have to admit that this is probably true, though I imagine print will likely persist for at least a few more generations, and will always have its uses (and will hopefully be kept as a contingency reserve in case the lights go out).

Ultimately, this is a boring game, betting on which technology will win out. But it’s interesting sometimes to analyze what motivates certain big cultural actors to wager the way they do.

If you think about it, it makes a lot of sense that Doctorow, generally an advocate for new technologies, wants to see print survive, and why despite his progressive edge, he’s a bit of a traditionalist. As a novelist, Doctorow is deeply invested in the economic model of print. That’s the way he actually sells books (and probably the way he likes to read them). And yet he grasps the Internet’s potential to leverage print — his career as a writer took off at precisely the moment when these two worlds entered into a complex symbiosis. As such, he has long been evangelizing the practice of giving away e-books to sell more print books, pointing to his own great success as proof of the hybrid concept.

At the surreal Google conference I attended at the New York Public Library in January, Doctorow took the stage as mollifier-in-chief, soothing the gathered representatives of the publishing industry with assurances that print is here to stay, is in fact reinforced by new online discovery tools like Google Book Search and free e-versions (which he suggests are used primarily for browsing or “market research”). All of this is right and true — for now — and Doctorow’s advice to publishers to loosen up and embrace the Web as a gateway toward offline reading experiences, and as a way to socially situate their texts on the network is good advice, but it doesn’t necessarily shed light on the longer term. The Poynter study, in its crude way, does.

Net-native writing will always be for a distracted audience, print for a captivated one, says Doctorow. He’s comfortable with that split. And I guess I’ve been too, suggesting as it does two sorts of knowledge, neither of which we’d want to lose. But the gap will almost certainly narrow, and figuring out the consequences of that is certainly one of our biggest challenges.

MediaCommons paper up in commentable form

We’ve just put up a version of a talk Kathleen Fitzpatrick has been giving over the past few months describing the genesis of MediaCommons and its goals for reinventing the peer review process. The paper is in CommentPress — unfortunately not the new version, which we’re still working on (revised estimated release late April), it’s more or less the same build we used for the Iraq Study Group Report. The exciting thing here is that the form of the paper, constructed to solicit reader feedback directly alongside the text, actually enacts its content: radically transparent peer-to-peer review, scholars talking in the open, shepherding the development each other’s work. As of this writing there are already 21 comments posted in the page margins by members of the editorial board (fresh off of last weekend’s retreat) and one or two others. This is an important first step toward what will hopefully become a routine practice in the MediaCommons community.

In less than an hour, Kathleen will be delivering the talk, drawing on some of the comments, at this event at the University of Rochester. Kathleen also briefly introduced the paper yesterday on the MediaCommons blog and posed an interesting question that came out of the weekend’s discussion about whether we should actually be calling this group the “editorial board.” Some interesting discussion ensued. Also check at this: “A First Stab at Some General Principles”.

MediaCommons editorial board convenes

Big things are stirring that belie the surface calm on this page. Bob, Eddie and I are down on the Jersey shore with the newly appointed editorial board of MediaCommons. Kathleen and Avi have assembled a brilliant and energetic group all dedicated to changing the forms and processes of scholarly communication in media studies and beyond. We’re thrilled to be finally together in the same room to start plotting out how this initiative will grow from a rudimentary sketch into a fully functioning networked press/community. The excitement here is palpable. Soon we’ll be posting some follow-up notes and a Comment Press edition of a paper by Kathleen. Stay tuned.

blooker nominees

The short list of nominees for Lulu.com’s second annual Blooker Prize, which is given to the year’s best book adapted from or based on a blog (or web comic), has been announced. This piece in the UK Times looks at how some publishers have begun more aggressively talent scouting in the blogosphere.

networked journalism in action

An excellent piece in the LA Times this weekend looks at how Josh Marshall’s little Talking Points Memo blog network led the journalistic charge that helped bring the US attorneys scandal to light. As the article details, TPM’s persistent muckraking was also instrumental in bringing national attention to the 2002 racial gaffe that cost Trent Lott his Senate leadership, to the Jack Abramoff lobbying scandals, and to the initially underappreciated public opposition to Bush’s plan to privatize social security. Truly a force to be reckoned with. And most important, it was all achieved through sustained collaboration with its readership:

The bloggers used the usual tools of good journalists everywhere — determination, insight, ingenuity — plus a powerful new force that was not available to reporters until blogging came along: the ability to communicate almost instantaneously with readers via the Internet and to deputize those readers as editorial researchers, in effect multiplying the reporting power by an order of magnitude.

In December, Josh Marshall, who owns and runs TPM , posted a short item linking to a news report in the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette about the firing of the U.S. attorney for that state. Marshall later followed up, adding that several U.S. attorneys were apparently being replaced and asked his 100,000 or so daily readers to write in if they knew anything about U.S. attorneys being fired in their areas.

For the two months that followed, Talking Points Memo and one of its sister sites, TPM Muckraker, accumulated evidence from around the country on who the axed prosecutors were, and why politics might be behind the firings. The cause was taken up among Democrats in Congress. One senior Justice Department official has resigned, and Atty. Gen. Alberto R. Gonzales is now in the media crosshairs.

This is precisely what Jeff Jarvis means by “networked journalism“: a more nuanced notion than “citizens journalism” in that it doesn’t insist on a strict distinction between professional and amateur. The emphasis instead is on a productive blurring of that boundary through collaboration and distribution of labor. There’s no doubt that what we’re seeing here is a democratization of the journalistic process, but this bottom-up movement doesn’t mean the end of hierarchy. Marshall and his small staff are clearly the leaders here, a new breed of editors coordinating complex chains of effort.