Alex Itin has done it again. Here it is: “Orson Whales,” an intertextual fantasia on Moby-Dick and Orson Welles set to the savage drums of John Bonham. Each frame is a page of this edition of the Melville text, painted and photographed and strung together in iMovie.

What you’re seeing is the entire book (actually two full copies – Alex can only paint on one side of each page because of bleed-through, so to get the whole text he had to double up). Here’s some of it stacked up in the studio (this is months of work):

The soundtrack is detritus gathered from web searches, a hunt for the white whale through a sea of tangents – appropriate, really, for the great book, which is so notoriously (and gloriously) tangential.

Alex: “The soundtrack is built from searching “moby dick” on You Tube (I was looking for Orson’s Preacher from the Huston film from the fifties) I couldn’t find the preacher, but did find tons of Led Zep and drummers doing Bonzo and a little Orson……. makes for a nice Melville in the end.”

Also check out his animation, same technique, of Ulysses. Bravo, Alex! (and happy birthday)!

Author Archives: ben vershbow

monkeybook 2: an evening with brad paley

Monkeybook is an occasional series of new media evenings hosted by the Institute for the Future of the Book at Monkeytown, Brooklyn’s premier video art venue. For our second event, we are thrilled to present brilliant interaction designer, friend and collaborator W. Bradford Paley, who will be giving a live tour of his work on four screens. Next Monday, May 7. New Yorkers, save the date!

Monkeybook is an occasional series of new media evenings hosted by the Institute for the Future of the Book at Monkeytown, Brooklyn’s premier video art venue. For our second event, we are thrilled to present brilliant interaction designer, friend and collaborator W. Bradford Paley, who will be giving a live tour of his work on four screens. Next Monday, May 7. New Yorkers, save the date!

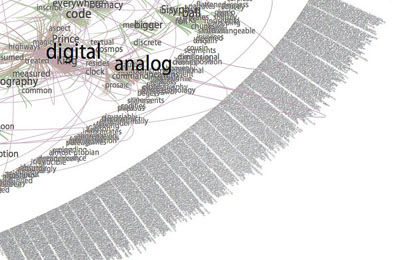

Brad is one of those rare individuals: an artist who is also a world-class programmer. His work focuses on making elegant, intuitive visualizations of complex data, in projects ranging from TextArc, a dazzling visual concordance of a text (a version of which was presented with the new Gamer Theory edition), to a wireless handheld device used by traders at the New York Stock Exchange to keep up with the blitz of transactions. It’s a crucial area of experimentation that addresses one of the fundamental problems of our time: how to make sense of too much information. And in a field frequently characterized by empty visual titillation, Brad’s designs evince a rare lucidity and usefulness. They convey meaning beautifully – and beauty meaningfully.

Brad is always inspiring when talking about his stuff, which is going to look absolutely stunning in the Monkeytown space. If you’re in the area, be sure not to miss this. For those of you who don’t know it, Monkeytown is unique among film venues in New York — an intimate room with a gigantic screen on each of its four walls, low comfy sofas and fantastic food. A strange and special place. If you think you can come, be sure to make a reservation ASAP as seating will be tight.

More info here.

(Monkeybook 1)

benevolent conspiracy

“Fuel prices jumped this week, led by gasoline which gained over a dollar a gallon on average. Oil distributors pointed to several “renegotiated” delivery contracts as proof that a long-rumored shortfall in the supply of U.S. oil has finally arrived. Oil producers were tight-lipped about the adjusted contracts, and as I write this it’s still unclear how extensive the shortfall will turn out to be.”

And thus the stage is set for World Without Oil, the social consciousness-raising ARG (alternate reality game) launched today by Jane McGonigal and associates. I’m already in flagrant violation of the “this is not a game” convention that governs all ARGs, but since this something I and others here at the Institute aim to follow closely in the coming weeks and months, we’ll have to treat the curtain between fact and fiction as semi-transparent.

From the perspective of our research here, I’m deeply intrigued because the ARG is an entirely net-native storytelling genre, employing forms as diverse and scattered as the media landscape we live in today. ARGs don’t rely on a specific software application, game system or OS, rather they treat the entire Internet as their platform. Players typically employ a whole battery of information technologies — email, chat, blogs, search engines, message boards, wikis, social media sites, cell phones — in pursuit of an elusive narrative thread.

The story is usually spun through cryptic clues and half-disclosures, one bread crumb at a time, by the game’s authors, or “puppetmasters.” To have any hope of success, players must work together, sharing clues and pooling information as they go. The whole point is to make the story into a group obsession — to mobilize players into problem-solving collectives where they can debate and test different hypotheses as a smart mob. It’s sort of like surfing an alternate version of the net, using all the social search tactics of the real one.

Of course, the net is a murky territory, full of conspiracy theories, identity traps and misinformation. ARGs take this uncertainty and make it their idiom. The game (remember, it’s not a game) might involve websites that to the casual observer look perfectly real — a corporate home page, a personal blog — but that are in fact a part of the fiction. ARGs use the playbook of spammers, phishers and social reality hackers like the Yes Men to create a fictional universe that blends seamlessly with the real.

But we’re not just talking about an alternate net here, we’re talking about an alternative world. ARGs frequently assign tasks that pull players away from their computers and propel them into their physical environment (the phenomenally popular I Love Bees had people running all over San Francisco answering pay phones). This couldn’t be more unlike the whole Second Life phenomenon (which, as you may have noticed, we’ve barely covered here). Instead of building a one-to-one simulacrum of the actual world (yeah yeah, you can fly, big whoop), this takes the actual world and tilts it — reinterprets it. There’s imagination happening here.

World Without Oil takes this in a new direction. McGonigal has been talking for some time now about using ARGs for more than just pure play. She believes they could be harnessed to solve real world problems (for more about this, read this recent long piece in SF Weekly by Eliza Strickland). Hence the premise of oil shocks. The WWO website was set up by ten friends who met in the chaos of the Denver Airport during the blizzards this past December. During that time, they bonded and got to talking about citizen journalism and the potential of the web for organizing masses of people to deal with crises without having to rely solely on big media and big government. A weird tip about an impending oil crisis on April 30th got their paranoid wheels turning and they decided to set up a central hub for netizens to send reportage and personal testimonies about life during the shocks. Today is April 30 and lo and behold: the shocks have arrived!

The idea is to collectively imagine a reality that could very likely come to pass, and to share information and ideas — alternative energy innovations, new forms of transport, new forms of community — that could help us get through it. It’s an opportunity for self-reeducation and perhaps the forging of some real-world relationships. There’s even a page for teachers to guide students through this collaborative hallucination, and to learn something about energy geopolitics as they do it.

As an entry to the serious games movement, this has to be one of the most innovative efforts out there. But I find myself wondering whether simply getting everyone to report from their corner of the crisis — postcards from the apocalypse –will be enough to create a full-blown ARG phenomenon. Is this participatory in quite the right way? While I ecstatically applaud the intention here of repurposing a form that to date has been employed mainly as a viral marketing tool (the first ARG was built around Spielberg’s “A.I.” in 2001), I worry that the WWO construct seems to have been shorn of most of the usual mystery elements — the codes, clues and crumbs — that make ARGs so addictive. There’s a whiff of homework here, something perhaps a little too earnest, that could prevent it from gaining traction. I sincerely hope I’m wrong.

Still, even if this fails to take off, I think this is an important milestone and will be important to study as it unfolds. WWO suggests what could be the ideal dystopian form for the cultural moment: a mode of storytelling that taps directly into the present human condition of networked information blitz and tries to channel it toward real-world awareness, or even action. The ARG adopts tactics long employed in military war games and conflict exercises and turns them (at least potentially) toward grassroots activism. WWO is trying to rouse, as Sebastian Mary put it in a previous post, our “democratic imagination. In SF Weekly piece I link to above, McGonigal puts it this way:

“When you start projecting that out to bigger scales, that’s when these games start to look like a real way to achieve, if not world peace, then some kind of world-benevolent conspiracy, where we feel like we are all playing the same game.”

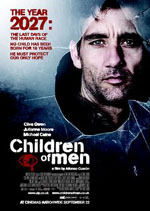

Many people I know loved the film “Children of Men” by Alfonso Cuarón because they felt that it showed them, with the cutting clarity of allegory, the way the world really is. The premise, that the human race has lost the ability to reproduce itself (a dying world, without children, slowly self-destructing), was of course implausible, but all the same it felt like a layer was being peeled away to reveal a terrible truth. Probably the most unsettling moment for me was the lights rose at the end and we exited the theater into the street. Everything looked different, fragile, like something awful was being hidden just beneath the surface. But the feeling soon faded and I filed the experience away: “Children of Men”; a brilliant film; one of the year’s best; shamefully overlooked at the Oscars.

Many people I know loved the film “Children of Men” by Alfonso Cuarón because they felt that it showed them, with the cutting clarity of allegory, the way the world really is. The premise, that the human race has lost the ability to reproduce itself (a dying world, without children, slowly self-destructing), was of course implausible, but all the same it felt like a layer was being peeled away to reveal a terrible truth. Probably the most unsettling moment for me was the lights rose at the end and we exited the theater into the street. Everything looked different, fragile, like something awful was being hidden just beneath the surface. But the feeling soon faded and I filed the experience away: “Children of Men”; a brilliant film; one of the year’s best; shamefully overlooked at the Oscars.

What would “Children of Men” look like as an ARG? What would a networked tactic bring to this story? Would it be simply dispatches from a dying world, or could we do something more constructive? Could the darkened theater and the streets outside somehow be merged?

Our first stories were oral stories. When we were children our parents read to us aloud stories that we listened to over and over again until they were embedded in our unconscious. We knew the stories inside and out, backwards and forwards. Reading became a ritual of call and response: a physical act. In the classroom too, teachers read aloud to us. We knew the stories inside and out, backwards and forwards. Call and response. At recess we ran out into the playground and re-eanacted the stories — replayed them, spun new ones. Those early experiences hearken back to earlier cultures — oral, pre-literate ones where the word was less the realm of contemplation and more the realm of action. ARGs seem to tap into this power of the oral story — the spark of the imagination and then the dash, together, into the playground.

gamer theory 2.0

…is officially live! Check it out. Spread the word.

I want to draw special attention to the Gamer Theory TextArc in the visualization gallery – a graphical rendering of the book that reveals (quite beautifully) some of the text’s underlying structures.

Gamer Arc detail

TextArc was created by Brad Paley, a brilliant interaction designer based in New York. A few weeks ago, he and Ken Wark came over to the Institute to play around with the Gamer Theory in TextArc on a wall display:

Ken jotted down some of his thoughts on the experience: “Brad put it up on the screen and it was like seeing a diagram of my own writing brain…” Read more here (then scroll down partway).

starting bottom-left, counter-clockwise: Ken, Brad, Eddie, Bob

More thoughts about all of this to come. I’ve spent the past two days running around like a madman at the Digital Library Federation Spring Forum in Pasadena, presenting our work (MediaCommons in particular), ducking in and out of sessions, chatting with interesting folks, and pounding away at the Gamer site — inserting footnote links, writing copy, generally polishing. I’m looking forward to regrouping in New York and processing all of this.

Thanks, Florian Brody for the photos.

Oh, and here is the “official” press/blogosphere release. Circulate freely:

The Institute for the Future of the Book is pleased to announce a new edition of the “networked book” Gamer Theory by McKenzie Wark. Last year, the Institute published a draft of Wark’s path-breaking critical study of video games in an experimental web format designed to bring readers into conversation around a work in progress. In the months that followed, hundreds of comments poured in from gamers, students, scholars, artists and the generally curious, at times turning into a full-blown conversation in the manuscript’s margins. Based on the many thoughtful contributions he received, Wark revised the book and has now published a print edition through Harvard University Press, which contains an edited selection of comments from the original website. In conjunction with the Harvard release, the Institute for the Future of the Book has launched a new Creative Commons-licensed, social web edition of Gamer Theory, along with a gallery of data visualizations of the text submitted by leading interaction designers, artists and hackers. This constellation of formats — read, read/write, visualize — offers the reader multiple ways of discovering and building upon Gamer Theory. A multi-mediated approach to the book in the digital age.

http://web.futureofthebook.org/mckenziewark/

More about the book:

Ever get the feeling that life’s a game with changing rules and no clear sides, one you are compelled to play yet cannot win? Welcome to gamespace. Gamespace is where and how we live today. It is everywhere and nowhere: the main chance, the best shot, the big leagues, the only game in town. In a world thus configured, McKenzie Wark contends, digital computer games are the emergent cultural form of the times. Where others argue obsessively over violence in games, Wark approaches them as a utopian version of the world in which we actually live. Playing against the machine on a game console, we enjoy the only truly level playing field–where we get ahead on our strengths or not at all.

Gamer Theory uncovers the significance of games in the gap between the near-perfection of actual games and the highly imperfect gamespace of everyday life in the rat race of free-market society. The book depicts a world becoming an inescapable series of less and less perfect games. This world gives rise to a new persona. In place of the subject or citizen stands the gamer. As all previous such personae had their breviaries and manuals, Gamer Theory seeks to offer guidance for thinking within this new character. Neither a strategy guide nor a cheat sheet for improving one’s score or skills, the book is instead a primer in thinking about a world made over as a gamespace, recast as an imperfect copy of the game.

——————-

The Institute for the Future of the Book is a small New York-based think tank dedicated to inventing new forms of discourse for the network age. Other recent publishing experiments include an annotated online edition of the Iraq Study Group Report (with Lapham’s Quarterly), Without Gods: Toward a History of Disbelief (with Mitchell Stephens, NYU), and MediaCommons, a digital scholarly network in media studies. Read the Institute’s blog, if:book. Inquiries: curator [at] futureofthebook [dot] org

McKenzie Wark teaches media and cultural studies at the New School for Social Research and Eugene Lang College in New York City. He is the author of several books, most recently A Hacker Manifesto (Harvard University Press) and Dispositions (Salt Publishing).

gamer theory 2.0 (beta)

The new Gamer Theory site is up, though for the next 24 hours we’re considering it beta. It’s all pretty much there except for some last bits and pieces (pop-up textual notes, a few explanatory materials, one or two pieces for the visualization gallery, miscellaneous tweaks). By all means start poking around and posting comments.

The project now has a portal page that links you to the constitutent parts: the Harvard print edition, two networked web editions (1.1 and 2.0), a discussion forum, and, newest of all, a gallery of text visualizations including a customized version of Brad Paley’s “TextArc” and a fascinating prototype of a progam called “FeatureLens” from the Human-Computer Interaction Lab at the University of Maryland. We’ll make a much bigger announcement about this tomorrow. For now, consider the site softly launched.

monkeys typing

Things are quiet here except for the soft patter of keyboards as we type/code/tweak away at Gamer Theory 2.0. The site goes live first thing Monday, at which point normal levels of conversation should resume. (Meanwhile, peaking out the window, it appears that spring has finally decided to arrive. Hallelujah!)

gamer theory update

Gamer Theory 2.0 is nearly there, we’re just taking a few extra few days to apply the finishing touches and to get a few last visualizations mounted in the gallery. The print edition from Harvard is available now.

For those of you in the city, there’s a great Gamer Theory event planned for tonight at the New School followed by drinks in Brooklyn at Barcade — a bar (as the name suggests) fitted out as a retro video game arcade (have a pint and play a round of Rampage, Gauntlet or Frogger). Here’s more info:

what: McKenzie Wark will present, and lead a discussion of his new book Gamer Theory (Harvard University Press). Jaeho Kang (Sociology, The New School for Social Reseach) will act as the respondent.

where: Wolff Conference Room, 2nd floor, 65 5th avenue (between 14th and 13th streets)

when: 6-8PM, Wednesday 18th April 2007

then: drinks & games at Barcade, 388 Union Ave Williamsburg (L train to Lorrimer st, take Union exit)

samizdat express

In his latest NY Times column, Edward Rothstein meditates on the vastness of the public domain and the pleasures of skimming it in simple digital editions prepared by B+R Samizdat Express. Since 1993 B+R, run by Barbara and Richard Seltzer of West Roxbury, Massachusetts, has been selling bundles of plain text (ASCII) digital literature scooped from Project Gutenberg and arranged by theme, genre or period into anthologies — first on floppy disc, and now on CD-ROM and DVD. It’s all stuff you can get for free by grazing the web’s various public domain repositories, but B+R have done the work of harvesting and sorting and they’ll ship these multi-shelf-spanning chunks to you for the price of a single print volume. Browse through nearly 200 book collections they’ve assembled so far and you’ll find packages ranging from “Anthropology and Myth” ($19), “Works of Guy de Maupassant” ($12), or “The American Revolution and Early Republic as witnessed by Mercy Warren and Others” ($19). Some works are provided in audio through text-to-voice conversion software.

As Rothstein notes, the bare-bones formatting and sheer volume of the anthologies makes these works hard to digest, but there’s no doubt B+R provides a valuable service, especially for people in places where books are scarce and net access unreliable. All in all, it’s an e-book advocate’s playground but more of a hallucinogenic head trip for the average reader — a way to sample vastness. It does make one’s wheels start to turn, though, on what other elucidating layers could be built on top of the vast murk of the digital library.

the new harpers.org

Harper’s has a new web concept designed by Paul Ford of F Train. History bears heavily on the refurbished site, almost overwhelmingly — especially compared to the stripped-down affair that preceded it. But considering that Harper’s has a more than ordinary amount of history to cart around — at 157 years, it’s the oldest general interest monthly in the United States — it makes sense that Ford and the editors had time on the brain. A journal that has published continuously since before the Civil War, on through Reconstruction, the Gilded Age, WWI, the Great Depression, WWII, civil rights, the 60s, the Cold War, right up to the present carries a hefty chunk of the national memory — and a lot of baggage, good and bad. So it’s fitting that the new design is packed with dates, inviting readers to dig into the past while also surveying the present. I can’t think of another news site in which the archives mingle so promiscuously with the front page spread. The result is a site that feels as much like a library as a periodical.

![]()

Directly beneath the title banner and above stories from the current issue is a highly compressed archive navigation, three rows tall. On the top row, Harper’s 16 decades fan out from left to right. Below them are the ten years of a given decade. Below that, the twelve months of a given year. Thus, every issue of Harper’s ever printed is just three clicks away. Of course, you need a subscription to view most of the content. (A hint, though: articles between the 1850 debut issue and 1899 are all available for free at the website of Cornell’s Making of America project, which undertook the task of scanning the first half-century’s worth of Harper’s.)

Clearly, the editors have been thinking a great deal about how to use the web to bring Harper’s‘ long, winding paper trail into the light and into use. The new design may be a little over-freighted, but shine light it does. By placing current events in such close proximity with the past, things are nested in a historical context — a refreshing expansion of scope next to the perpetual present of the 24-hour news cycle. Already there are a few features that help connect the dots. One is “topic pages” that allow readers to track particular subjects through the archive. Take a look, for example, at this trail of links for “South Africa”:

- 4 Images from 1983 to 2001

- 67 Articles from 1850 to 2007

- 2 Cartoons from 1985

- 44 Events from 2000 to 2007

- 10 Facts from 1999 to 2006

- 4 Stories from 1888 to 1983

- 2 Jokes from 1881 to 1912

- 4 Photographs from 1987 to 2001

- 1 Poem from 1883

- 6 Reviews from 1887 to 2005

A smart next step would be to let readers trace, tag and document their own research trails and share those with other readers. This could be an added incentive for a new generation of Harper’s subscribers: access not only to an invaluable historical archive but to a social architecture in which communities and individuals could interpret that archive and bring it into conversation with the contemporary.

“spring_alpha” and networked games

Jesse’s post yesterday pondering the possibility of networked comics reminded me of an interesting little piece I came across last month on the Guardian Gamesblog by Aleks Krotoski on networked collaboration — or rather, the conspicuous lack thereof — in games. The post was a lament really, sparked by Krotoski’s admiration of the Million Penguins project, which for her threw into stark relief the game industry’s troubling retentiveness regarding the means of game production:

Meanwhile in gameland, where non-linearity is the ideal, we’re at odds with the power of games as the world’s most compelling medium and the industry’s desperate attempts to integrate with the so-called worthy (yet linear) media. And ironically, we’ve been lapped by books. How embarrassing. If anyone should have pushed the user-generated boat out, it should have been the games industry.

…Sure, there are a few new outlets for budding designers to reap the kudos or the ridicule of their peers, but there’s not a WikiGame in sight. Until platform owners have the courage to open their consoles to players, a million penguins will go elsewhere. And so will gamers.

Well I just came across a very intriguing UK-based project that might qualify as a wiki-game, or more or less the equivalent. It’s called “spring_alpha” and is by all indications a game world that is openly rewritable on both the narrative and code level. What’s particularly interesting is that the participatory element is deeply entwined with the game’s political impulses — it’s an experiment in rewriting the rules of a repressive society. As described by the organizers:

Well I just came across a very intriguing UK-based project that might qualify as a wiki-game, or more or less the equivalent. It’s called “spring_alpha” and is by all indications a game world that is openly rewritable on both the narrative and code level. What’s particularly interesting is that the participatory element is deeply entwined with the game’s political impulses — it’s an experiment in rewriting the rules of a repressive society. As described by the organizers:

“spring_alpha” is a networked game system set in an industrialised council estate whose inhabitants are attempting to create their own autonomous society in contrast to that of the regime in which they live. The game serves as a “sketch pad” for testing out alternative forms of social practice at both the “narrative” level, in terms of the game story, and at a “code” level, as players are able to re-write the code that runs the simulated world.

…’spring_alpha’ is a game in permanent alpha state, always open to revision and re-versioning. Re-writing spring_alpha is not only an option available to coders however. Much of the focus of the project lies in using game development itself as a vehicle for social enquiry and speculation; the issues involved in re-designing the game draw parallels with those involved in re-thinking social structures.

My first thought is that, unlike A Million Penguins, “spring_alpha” provides a robust armature for collaboration: a fully developed backstory/setting as well as an established visual aesthetic (both derived from artist Chad McCail’s 1998 work “Spring”). That strikes me as a recipe for success. In the graphics, sound and controls department, “spring_alpha” doesn’t appear particularly cutting edge (it looks a bit like Google SketchUp, though that may have just been in the development modules I saw), but its sense of distributed creativity and of the political possibilities of games seem quite advanced.

Can anyone point to other examples of collaboratively built games? Does Second Life count?