New partners and new features. Google has been busy lately building up Book Search. On the institutional end, Ghent, Lausanne and Mysore are among the most recent universities to hitch their wagons to the Google library project. On the user end, the GBS feature set continues to expand, with new discovery tools and more extensive “about” pages gathering a range of contextual resources for each individual volume.

Recently, they extended this coverage to books that haven’t yet been digitized, substantially increasing the findability, if not yet the searchability, of thousands of new titles. The about pages are similar to Amazon’s, which supply book browsers with things like concordances, “statistically improbably phrases” (tags generated automatically from distinct phrasings in a text), textual statistics, and, best of all, hot-linked lists of references to and from other titles in the catalog: a rich bibliographic network of interconnected texts (Bob wrote about this fairly recently). Google’s pages do much the same thing but add other valuable links to retailers, library catalogues, reviews, blogs, scholarly resources, Wikipedia entries, and other relevant sites around the net (an example). Again, many of these books are not yet full-text searchable, but collecting these resources in one place is highly useful.

It makes me think, though, how sorely an open source alternative to this is needed. Wikipedia already has reasonably extensive articles about various works of literature. Library Thing has built a terrific social architecture for sharing books. There are a great number of other freely accessible resources around the web, scholarly database projects, public domain e-libraries, CC-licensed collections, library catalogs.

Could this be stitched together into a public, non-proprietary book directory, a People’s Card Catalog? A web page for every book, perhaps in wiki format, wtih detailed bibliographic profiles, history, links, citation indices, social tools, visualizations, and ideally a smart graphical interface for browsing it. In a network of books, each title ought to have a stable node to which resources can be attached and from which discussions can branch. So far Google is leading the way in building this modern bibliographic system, and stands to turn the card catalogue of the future into a major advertising cash nexus. Let them do it. But couldn’t we build something better?

Author Archives: ben vershbow

digital wasteland

In a technology-driven culture where planned obsolescence and perpetual upgrades are the rule, electronic waste – the computer hardware and consumer electronics we continuously discard – is becoming a problem of epidemic proportions. 20 to 50 million tons of it are generated annually, most of which gets shipped off to places like India, China and Kenya, where complex scavenger economies have sprung up around vast electronics dumping grounds filled with leaking toxins and treacherous chemicals. Foreign Policy just published a powerful photo essay documenting this very real footprint left by our so-called virtual lives.

Of course it’s not just what we throw away that’s problematic, but what we consume. Many today are awakening to the fact that most of the industrial conveniences we enjoy – abundant food shipped from anywhere, cheap transportation, and various other luxuries – carry a dire hidden cost to the planet’s fragile climate and ecology. Like it or not, instant and ubiquitous communication through digital networks also requires fuel. It was recently estimated that the average Second Life avatar consumes as much energy annually (all those servers huffing and puffing) as the average Brazilian.

There are other stories that reveal the uncleanness of our technology. Read this section (paragraphs 45 and 46) of Gamer Theory about the tragic case of coltan mining in Congo. Coltan is a rare mineral used to make conductors in the Sony Playstation, and its scarcity and high demand have made it the source of violent conflict in that country.

These are problems that are difficult to wrap one’s mind around, so totally do they challenge our fundamental patterns of existence. One can begin, I suppose, by acting locally. On a crisp, sunny day in New York this past January, walking across a large stretch of asphalt on the north end of Union Square usually populated by organic farmers’ stalls or packs of skateboarders idly rehearsing their moves, I found myself standing before a sea of old computers, cellphones and other discarded electronics spread out across the ground. As I stared agape, energetic volunteers, bundled up against the cold, darted around the piles, sorting, wrapping and carting the junk into a large truck. It was a computer recycling drive organized by the Lower East Side Ecology Center in partnership with the NYCWasteLe$$ program. A heartening sight that I couldn’t resist recording with my cameraphone.

Here’s a little photo essay from our neck of the woods:

are you being served?

Just a quick heads up – today we migrated all of our sites to a new server, so if you notice anything wonky that’s probably the reason. Feel free to report weird buggy-looking things to curator [at] futureofthebook [dot] org. Thanks!

sketches toward peer-to-peer review

Last Friday, Clancy Ratliff gave a presentation at the Computers and Writing Conference at Wayne State on the peer-to-peer review system we’re developing at MediaCommons. Clancy is on the MC editorial board so the points in her slides below are drawn directly from the group’s inaugural meeting this past March. Notes on this and other core elements of the project are sketched out in greater detail here on the MediaCommons blog, but these slides give a basic sense of how the p2p review process might work.

promiscuous materials

This began as a quick follow-up to my post last week on Jonathan Lethem’s recent activities in the area of copyright activism. But after a couple glasses of sake and some insomnia it mutated into something a bit bigger.

Back in March, Lethem announced that he planned to give away a free option on the film rights of his latest novel, You Don’t Love Me Yet. Interested filmmakers were invited to submit a proposal outlining their creative and financial strategies for the project, provided that they agreed to cede a small cut of proceeds if the film ends up getting distributed. To secure the option, an artist also had to agree up front to release ancillary rights to their film (and Lethem, likewise, his book) after a period of five years in order to allow others to build on the initial body of work. Many proposals were submitted and on Monday Lethem granted the project to Greg Marcks, whose work includes the feature “11:14.”

What this experiment does, and quite self-consciously, is demonstrate the curious power of the gift economy. Gift giving is fundamentally a ritual of exchange. It’s not a one-way flow (I give you this), but a rearrangement of social capital that leads, whether immediately or over time, to some sort of reciprocation (I give you this and you give me something in return). Gifts facilitate social equilibrium, creating occasions for human contact not abstracted by legal systems or contractual language. In the case of an artistic or scholarly exchange, the essence of the gift is collaboration. Or if not a direct giving from one artist to another, a matter of influence. Citations, references and shout-outs are the acknowledgment of intellectual gifts given.

By giving away the film rights, but doing it through a proposal process which brought him into conversation with other artists, Lethem purchased greater influence over the cinematic translation of his book than he would have had he simply let it go, through his publisher or agent, to the highest bidder. It’s not as if novelists and directors haven’t collaborated on film adaptations before (and through more typical legal arrangements) but this is a significant case of copyright being put to the side in order to open up artistic channels, changing what is often a business transaction — and one not necessarily even involving the author — into a passing of the creative torch.

Another Lethem experiment with gift economics is The Promiscuous Materials Project, a selection of his stories made available, for a symbolic dollar apiece, to filmmakers and dramatists to adapt or otherwise repurpose.

One point, not so much a criticism as an observation, is how experiments such as these — and you could compare Lethem’s with Cory Doctorow’s, Yochai Benkler’s or McKenzie Wark’s — are still novel (and rare) enough to serve doubly as publicity stunts. Surveying Lethem’s recent free culture experiments it’s hard not to catch a faint whiff of self-congratulation in it all. It’s oh so hip these days to align one’s self with the Creative Commons and open source culture, and with his recent foray into that arena Lethem, in his own idiosyncratic way, joins the ranks of writers shrewdly riding the wave of the Web to reinforce and even expand their old media practice. But this may be a tad cynical. I tend to think that the value of these projects as advocacy, and in a genuine sense, gifts, outweighs the self-promotion factor. And the more I read Lethem’s explanations for doing this, the more I believe in his basic integrity.

It does make me wonder, though, what it would mean for “free culture” to be the rule in our civilization and not the exception touted by a small ecstatic sect of digerati, some savvy marketers and a few dabbling converts from the literary establishment. What would it be like without the oppositional attitude and the utopian narratives, without (somewhat paradoxically when you consider the rhetoric) something to gain?

In the end, Lethem’s open materials are, as he says, promiscuities. High-concept stunts designed to throw the commodification of art into relief. Flirtations with a paradigm of culture as old as the Greek epics but also too radically new to be fully incorporated into the modern legal-literary system. Again, this is not meant as criticism. Why should Lethem throw away his livelihood when he can prosper as a traditional novelist but still fiddle at the edges of the gift economy? And doesn’t the free optioning of his novel raise the stakes to a degree that most authors wouldn’t dare risk? But it raises hypotheticals for the digital age that have come up repeatedly on this blog: what does it mean to be a writer in the infinitely reproducible non-commodifiable Web? what is the writer after intellectual property?

copyright unlimited

Larry Lessig has set up a wiki for a collective response to Mark Helprin’s idiotic op-ed in yesterday’s Times arguing for perpetual copyright.

On Teleread, David Rothman also weighs in.

a new voice for copyright reform

The novelist Jonathan Lethem has been on a most unusual book tour, promoting and selling his latest novel and at the same time publicly questioning the copyright system that guarantees his livelihood. Intellectual property is a central theme in his new book, You Don’t Love Me Yet, which chronicles a struggling California rock band who, in the course of trying to compose and record a debut album, progressively lose track of who wrote their songs. Lethem has always been obsessed with laying bare his influences (he has a book of essays devoted in large part to that), but this new novel, which seems on the whole to be a slighter work than his previous two Brooklyn-based sagas, is his most direct stab to date at the complex question of originality in art.

The novelist Jonathan Lethem has been on a most unusual book tour, promoting and selling his latest novel and at the same time publicly questioning the copyright system that guarantees his livelihood. Intellectual property is a central theme in his new book, You Don’t Love Me Yet, which chronicles a struggling California rock band who, in the course of trying to compose and record a debut album, progressively lose track of who wrote their songs. Lethem has always been obsessed with laying bare his influences (he has a book of essays devoted in large part to that), but this new novel, which seems on the whole to be a slighter work than his previous two Brooklyn-based sagas, is his most direct stab to date at the complex question of originality in art.

In February Lethem published one of the better pieces that has been written lately about the adverse effects of our bloated copyright system, an essay in Harper’s entitled “The Ecstasy of Influence,” which he billed provocatively as “a plagiarism.” Lethem’s flippancy with the word is deliberate. He wants to initiate a discussion about what he sees as the ultimately paradoxical idea of owning culture. Lethem is not arguing for an abolition of copyright laws. He still wants to earn his bread as a writer. But he advocates a general relaxation of a system that has clearly grown counter to the public interest.

None of these arguments are particularly new but Lethem reposes them deftly, interweaving a diverse playlist of references and quotations from greater authorities from with the facility of a DJ. And by foregrounding the act of sampling, the essay actually enacts its central thesis: that all creativity is built on the creativity of others. We’ve talked a great deal here on if:book about the role of the writer evolving into something more like that of a curator or editor. Lethem’s essay, though hardly the first piece of writing to draw heavily from other sources, demonstrates how a curatorial method of writing does not necessarily come at the expense of a distinct authorial voice.

The Harper’s piece has made the rounds both online and off and, with the new novel, seems to have propelled Lethem, at least for the moment, into the upper ranks of copyright reform advocates. Yesterday The Washington Post ran a story on Lethem’s recent provocations. Here too is a 50-minute talk from the Authors@Google series (not surprisingly, Google is happy to lend some bandwidth to these ideas).

For some time, Cory Doctorow has been the leading voice among fiction writers for a scaling back of IP laws. It’s good now to see a novelist with more mainstream appeal stepping into the debate, with the possibility of moving it beyond the usual techno-centric channels and into the larger public sphere. I suspect Lethem’s interest will eventually move on to other things (and I don’t see him giving away free electronic versions of his books anytime soon), but for now, we’re fortunate to have his pen in the service of this cause.

why is ‘world without oil’ such a bore?

I just had the following email exchange with Sebastian Mary about the World Without Oil alternate reality game (covered previously on if:book here and here). It seemed interesting enough to repost here.

BEN – Mon, May 14, 2007 at 4:59 PM EST

Hi there,

You found anything interesting yet going on at WWO?

I keep meaning to dig deeper, but nothing I’ve turned up is much good. Maudlin postcards from a pretty generic-feeling apocalypse is what most of it feels like to me. Perhaps I haven’t been looking in the right places, but my instinct at the moment is that the citizen journalist conceit was not the way to go. It’s “participatory” all right, but in that bland, superficial way that characterizes so many traditional media efforts at “interactivity.” Honestly, I’m surprised something like this got through the filter of folks as sophisticated as Jane McGonigal and co.

I think players need smaller pieces and hooks, elements of mystery to get their wheels turning — a story. As far as I can tell, this is the closest to intrigue there’s yet been, and it turned out to be nothing.

Would love to be shown something that suggests otherwise. Got anything?

Ben

SEB MARY – Mon, May 14, 2007 at 5:25 PM

Haven’t been following it closely to be honest. Up to the eyeballs with other work and don’t really have time to trawl acres of second-rate ‘What if…’. Plus, if I’m honest, despite my fetish for collaborative and distributed creativity I’m fussy about good prose, and amateur ‘creative writing’ doesn’t really grip me unless it’s so far from tradition (eg lolcats and the like) as to be good on its own terms. So though the idea intrigued me, I’ve not been hooked. I think it probably needs more story.

Which problem actually resonates with something else I’ve been pondering recently around collaborative writing. It bothers me that because people aren’t very good at setting up social structures within which more than one person can work on the same story (the total lack of anything of that sort in Million Penguins for example), you end up with this false dichotomy between quality products of one mind, and second-rate products of many, that ends up reinforcing the privileged position of the Author simply because people haven’t worked out an effective practice for any alternative. I think there’s something to be learned from the open-source coders about how you can be rigorous as well as collaborative.

sMary

BEN – Tue, May 15, 2007 at 12:50 AM

I don’t see why an ARG aimed at a social mobilization has to be so goddamn earnest. It feels right now like a middle school social studies assignment. But it could be subversive, dangerous and still highly instructive. Instead of asking players to make YouTube vids by candlelight, or Live Journal diaries reporting gloomily on around-the-block gas lines or the promise of local agriculture, why not orchestrate some real-world mischief, as is done in other ARGs.

This game should be generating memorable incursions of the hypothetical into the traffic of daily life, gnawing at the edges of people’s false security about energy. Create a car flash mob at a filling station and tie up several blocks of traffic in a cacophony of horns, maybe even make it onto the evening news. Or re-appropriate public green spaces for the planting of organic crops, like those California agrarian radicals with their “conspiracies of soil” in People’s Park back in the 60s. WWO’s worst offense, I think, is that it lacks a sense of humor. To sort of quote Oscar Wilde, the issues here are too important to take so seriously.

Ben

SEB MARY – Tue, May 15, 2007 at 5:34 AM

I totally agree that a sense of humour would make all the difference. There’s a flavour about it of top-down didactically-oriented pseudo-‘participation’, which in itself is enough to scupper something networked, even before you consider the fact that very few people like being lectured at in story form.

The trouble is, that humour around topics like this would index the PMs squarely to an activist agenda that includes people like the Reverend Billy, the Clown Army and their ilk. That’d be ace in my view; but it’s a risky strategy for anyone who’s reluctant to nail their political colours firmly to the anti-capitalist mast, which – I’d imagine – rules out most of Silicon Valley. It’s hard to see how you could address an issue like climate change in an infectious and mischievous way without rubbing a lot of people up the wrong way; I totally don’t blame McGonigal for having a go, but I think school-assignment-type pretend ‘citizen journalism’ is no substitute for playful subversiveness and – as you say – story hooks.

The other issue in play is as old as literary theory: the question of whether you dig ideas-based narrative or not. If the Hide & Seek Fest last weekend is anything to go by, the gaming/ARG community, young as it is, is already debating this. What place does ‘messaging’ have in games? Some see gaming as a good vehicle for inspiring, radical, even revolutionary messages, and some maintain that this misses the point.

Certainly, I think you have to be careful: games and stories have their own internal logic, and often don’t take kindly to being loaded with predetermined arguments. Even if I like the message, I think that it only works if it’s at the service of the experience (read story, game or both), and not the other way round. Otherwise it doesn’t matter how much interactivity you add, or how laudable your aim, it’s still boring.

sMary

a new face(book) for wikipedia?

It was pointed out to me the other day that Facebook has started its own free classified ad service, Facebook Marketplace (must be logged in), a sort of in-network Craigslist poised to capitalize on a built-in userbase of over 20 million. Commenting on this, Nicholas Carr had another thought:

But if Craigslist is a big draw for Facebook members, my guess is that Wikipedia is an even bigger draw. I’m too lazy to look for the stats, but Wikipedia must be at or near the top of the list of sites that Facebookers go to when they leave Facebook. To generalize: Facebook is the dorm; Wikipedia is the library; and Craigslist is the mall. One’s for socializing; one’s for studying; one’s for trading.

Which brings me to my suggestion for Zuckerberg [Facebook founder]: He should capitalize on Wikipedia’s open license and create an in-network edition of the encyclopedia. It would be a cinch: Suck in Wikipedia’s contents, incorporate a Wikipedia search engine into Facebook (Wikipedia’s own search engine stinks, so it should be easy to build a better one), serve up Wikipedia’s pages in a new, better-designed Facebook format, and, yes, incorporate some advertising. There may also be some social-networking tools that could be added for blending Wikipedia content with Facebook content.

Suddenly, all those Wikipedia page views become Facebook page views – and additional ad revenues. And, of course, all the content is free for the taking. I continue to be amazed that more sites aren’t using Wikipedia content in creative ways. Of all the sites that could capitalize on that opportunity, Facebook probably has the most to gain.

I’ve often thought this — not the Facebook idea specifically, but simply that five to ten years (or less) down the road, we’ll probably look back bemusedly on the days when we read Wikipedia on the actual Wikipedia site. We’ve grown accustomed to, even fond of it, but Wikipedia does still look and feel very much like a place of production, the goods displayed on the factory floor amid clattering machinery and welding sparks (not to mention periodic labor disputes). This blurring of the line between making and consuming is, of course, what makes Wikipedia such a fascinating project. But it does seem like it’s just a matter of time before the encyclopedia starts getting spun off into glossier, ad-supported packages. What other captive audience networks might be able to pull off their own brand of Wikipedia?

chromograms: visualizing an individual’s editing history in wikipedia

The field of information visualization is cluttered with works that claim to illuminate but in fact obscure. These are what Brad Paley calls “write-only” visualizations. If you put information in but don’t get any out, says Paley, the visualization has failed, no matter how much it dazzles. Brad discusses these matters with the zeal of a spiritual seeker. Just this Monday, he gave a master class in visualization on two laptops, four easels, and four wall screens at the Institute’s second “Monkeybook” evening at our favorite video venue in Brooklyn, Monkeytown. It was a scintillating performance that left the audience in a collective state of synaptic arrest.

Jesse took some photos:

We stand at a crucial juncture, Brad says, where we must marshal knowledge from the relevant disciplines — design, the arts, cognitive science, engineering — in order to build tools and interfaces that will help us make sense of the huge masses of information that have been dumped upon us with the advent of computer networks. All the shallow efforts passing as meaning, each pretty piece of infoporn that obfuscates as it titillates, is a drag on this purpose, and a muddying of the principles of “cognitive engineering” that must be honed and mastered if we are to keep a grip on the world.

With this eloquent gospel still echoing in my brain, I turned my gaze the next day to a new project out of IBM’s Visual Communication Lab that analyzes individuals’ editing histories in Wikipedia. This was produced by the same team of researchers (including the brilliant Fernanda Viegas) that built the well known History Flow, an elegant technique for visualizing the revision histories of Wikipedia articles — a program which, I think it’s fair to say, would rate favorably on the Paley scale of readability and illumination. Their latest effort, called “Chromograms,” hones in the activities of individual Wikipedia editors.

The IBM team is interested generally in understanding the dynamics of peer to peer labor on the internet. They’ve focused on Wikipedia in particular because it provides such rich and transparent records of its production — each individual edit logged, many of them discussed and contextualized through contributors’ commentary. This is a juicy heap of data that, if placed under the right set of lenses, might help make sense of the massively peer-produced palimpsest that is the world’s largest encyclopedia, and, in turn, reveal something about other related endeavors.

Their question was simple: how do the most dedicated Wikipedia contributors divvy up their labor? In other words, when someone says, “I edit Wikipedia,” what precisely do they mean? Are they writing actual copy? Fact checking? Fixing typos and syntactical errors? Categorizing? Adding images? Adding internal links? External ones? Bringing pages into line with Wikipedia style and citation standards? Reverting vandalism?

All of the above, of course. But how it breaks down across contributors, and how those contributors organize and pace their work, is still largely a mystery. Chromograms shed a bit of light.

For their study, the IBM team took the edit histories of Wikipedia administrators: users to whom the community has granted access to the technical backend and who have special privileges to protect and delete pages, and to block unruly users. Admins are among the most active contributors to Wikipedia, some averaging as many as 100 edits per day, and are responsible more than any other single group for the site’s day-to-day maintenance and governance.

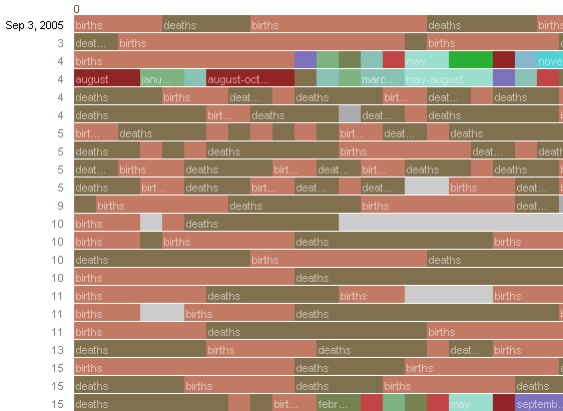

What the researches essentially did was run through the edit histories with a fine-toothed, color-coded comb. A chromogram consists of multiple rows of colored tiles, each tile representing a single edit. The color of the tile corresponds with the first letter of the text in the edit, or in the case of “comment chromograms,” the first letter of the user’s description of their edit. Colors run through the alphabet, starting with numbers 1-10 in hues of gray and then running through the ROYGBIV spectrum, A (red) to violet (Z).

It’s a simple system, and one that seems arbitrary at first, but it accomplishes the important task of visually separating editorial actions, and making evident certain patterns in editors’ workflow.

Much was gleaned about the way admins divide their time. Acvitity often occurs in bursts, they found, either in response to specific events such as vandalism, or in steady, methodical tackling of nitpicky, often repetitive, tasks — catching typos, fixing wiki syntax, labeling images etc. Here’s a detail of a chromogram depicting an administrator’s repeated entry of birth and death information on a year page:

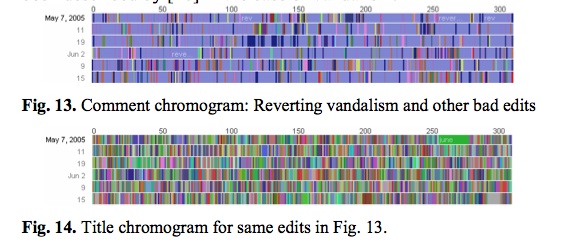

The team found that this sort of systematic labor was often guided by lists, either to-do lists in Wikiprojects, or lists of information in articles (a list of naval ships, say). Other times, an editing spree simply works progressively through the alphabet. The way to tell? Look for rainbows. Since the color spectrum runs A to Z, rainbow patterned chromograms depict these sorts of alphabetically ordered tasks. As in here:

This next pair of images is almost moving. The top one shows one administrator’s crusade against a bout of vandalism. Appropriately, he’s got the blues, blue corresponding with “r” for “revert.” The bottom image shows the same edit history but by article title. The result? A rainbow. Vandalism from A to Z.

Chromograms is just one tool that sheds light on a particular sort of editing activity in Wikipedia — the fussy, tedious labors of love that keep the vast engine running smoothly. Visualizing these histories goes some distance toward explaining how the distributed method of Wikipedia editing turns out to be so efficient (for a far more detailed account of what the IBM team learned, it’s worth reading this pdf). The chromogram technique is probably too crude to reveal much about the sorts of editing that more directly impact the substance of Wikipedia articles, but it might be a good stepping stone.

Learning how to read all the layers of Wikipedia is necessarily a mammoth undertaking that will require many tools, visualizations being just one of them. High-quality, detailed ethnographies are another thing that could greatly increase our understanding. Does anyone know of anything good in this area?