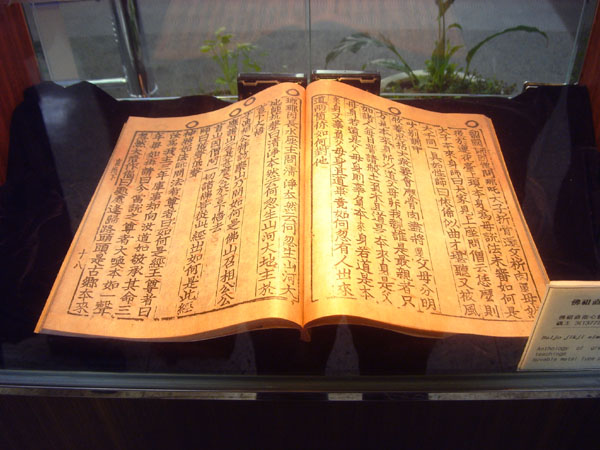

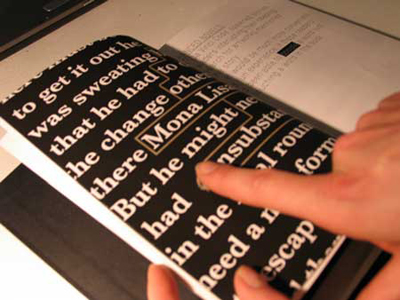

Manolis Kelaidis, a designer at the Royal College of Art in London, has found a way to make printed pages digitally interactive. His “blueBook” prototype is a paper book with circuits embedded in each page and with text printed with conductive ink. When you touch a “linked” word on the page and your finger completes a circuit, sending a signal to a processor in the back cover which communicates by Bluetooth with a nearby computer, bringing up information on the screen.

(image from booktwo.org)

I’ve heard from a number of people that Kelaidis brought down the house last week at O’Reilly’s “Tools of Change for Publishing” conference in San Jose. Andrea Laue, who blogs at jusTaText, did a nice write-up:

He asked the audience if, upon encountering an obscure reference or foreign word on the page of a book, we would appreciate the option of touching the word on the page and being taken (on our PC) to an online resource that would identify or define the unfamiliar word. Then he made it happen. Standing O.

Yes, he had a printed and bound book which communicated with his laptop. He simply touched the page, and the laptop reacted. It brought up pictures of the Mona Lisa. It translated Chinese. It played a piece of music. Kelaidis suggested that a library of such books might cross-refer, i.e. touching a section in one book might change the colors of the spines of related books on your shelves. Imagine.

So there you have it. A networked book – in print. Amazing.

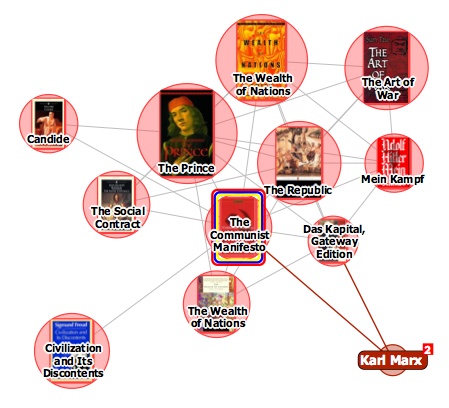

It’s not surprising to hear that the O’Reilly crowd, filled with anxious publishers, was ecstatic about the blueBook. Here was tangible proof that print can be meaningfully integrated with the digital world without sacrificing its essential formal qualities: the love child of the printed book and the companion CD-ROM. And since so much of the worry in publishing is really about the crumbling of business models and only secondarily about the essential nature of books or publishing, it was no doubt reassuring to imagine something like the blueBook as the digital book of the future: a physical object that can be reliably bought and sold (and which, with all those conductors, circuits and processors involved, would be exceedingly difficult to copy).

Kelaidis’ invention definitely sounds wonderful, but is it a plausible vision of things to come? I suppose electronic paper of all kinds, pulp and polymer, will inevitably get better and cheaper over time. How transient and historically contingent is our attachment to paper? There’s a compelling argument to be made (Gary Frost makes it, and we frequently debate it around the table here) that, in spite of all the new possibilities opened up by digital technologies, the paper book is a unique ergonomic fit for the human hand and mind, and, moreover, that its “bounded” nature allows for a kind of reading that people will want to keep distinct from the more fragmentary and multi-directional forms of reading we do on computers and online. (That’s certainly my personal reading strategy these days.) Perhaps, with something like the blueBook, it would be possible to have the best of both worlds.

But what about accessibility? What about trees? By the time e-paper is a practical reality, will attachment to print have definitively ebbed? Will we be used to a greater degree of interactivity (the ability not only to link text but to copy, edit and recombine it, and to mix it directly, on the “page,” with other media) than even the blueBook can provide?

Subsequent thought:A discussion about this on an email list I subscribe to reminded me of the intellectual traps that I and many others fall into when speculating about future technologies: the horse race (which technology will win?), the either/or question. What do I really think? The future of the book is not monolithic but rather a multiplicity of things – the futures of the book – and I expect (and hope) that well-crafted hyrbrid works like Kelaidis’ will be among those futures./thought

We just found out that next week Kelaidis will be spending a full day at the Institute so we’ll be able to sift through some of these questions in person.