At long last, we are pleased to release CommentPress, a free, open source theme for the WordPress blog engine designed to allow paragraph-by-paragraph commenting in the margins of a text. To download it and get it running in your WordPress installation, go to our dedicated CommentPress site. There you’ll find everything you need to get started. This 1.0 release represents the most basic out-of-the-box version of the theme. Expect many improvements and new features in the days and weeks ahead (some as soon as tomorrow). We could have kept refining it for another week but we felt that the time was well past due to get it out in the world and to let the community development cycles begin. So here it is:

/commentpress/ »

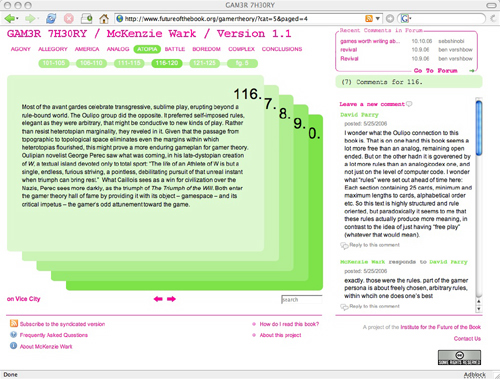

This little tool is the happy byproduct of a year and a half spent hacking WordPress to see whether a popular net-native publishing form, the blog, which, most would agree, is very good at covering the present moment in pithy, conversational bursts but lousy at handling larger, slow-developing works requiring more than chronological organization – ?whether this form might be refashioned to enable social interaction around long-form texts. Out of this emerged a series of publishing experiments loosely grouped under the heading “networked books.” The first of these, McKenzie Wark’s GAM3R 7H30RY 1.1, was a wildly inventive text whose aphoristic style and modular structure lent it readily to “chunking” into digestible units for online discussion. This is how it ended up looking:

In the course of our tinkering, we achieved one small but important innovation. Placing the comments next to rather than below the text turned out to be a powerful subversion of the discussion hierarchy of blogs, transforming the page into a visual representation of dialog, and re-imagining the book itself as a conversation. Several readers remarked that it was no longer solely the author speaking, but the book as a whole (author and reader, in concert).

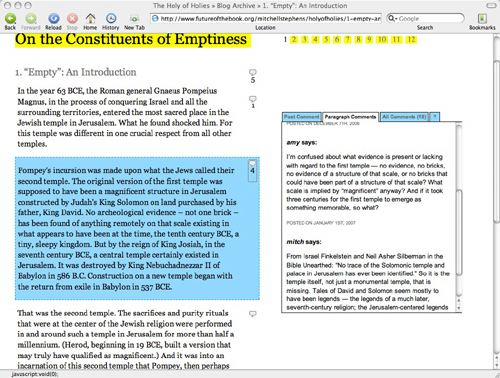

Toying with the placement of comments was relatively easy to do with Gamer Theory because of its unusual mathematical structure (25 paragraphs per chapter, 250 words or lessper paragraph), but the question remained of how this format could be applied to expository texts of more variable shapes and sizes. The breakthrough came with Mitchell Stephens’ paper, The Holy of Holies: On the Constituents of Emptiness. The solution we found was to have the comment area move with you in the right hand column as you scrolled down the page, changing its contents depending on which paragraph in the left hand column you selected. This format was inspired in part by a WordPress commenting system developed by Jack Slocum and by the Free Software Foundation’s site for community review of drafts of the GNU General Public License. Drawing on these terrific examples, we at last managed to construct a template that might eventually be exported as a simple toolset applicable to any text.

Ever since “Holy of Holies,” people have been clamoring for us to release CommentPress as a plugin so they could start playing with it, improving it and customizing it for more specialized purposes. Now it’s finally here, with a cleaned-up codebase and a simpler interface, and we can’t wait to see how people start putting it to use. We can imagine a number of possibilities:

-? scholarly contexts: working papers, conferences, annotation projects, journals, collaborative glosses

-? educational: virtual classroom discussion around readings, study groups

-? journalism/public advocacy/networked democracy: social assessment and public dissection of government or corporate documents, cutting through opaque language and spin (like our version of the Iraq Study Group Report, or a copy of the federal budget, or a Walmart press release)

-? creative writing: workshopping story drafts, collaborative storytelling

-? recreational: social reading, book clubs

Once again, there are dozens of little details we want to improve, and no end of features we would love to see developed. Our greatest hope for CommentPress is that it take on a life of its own in the larger community. Who knows, it could provide a base for something far more ambitious.

An important last thought, however. While CommentPress presents exciting possibilities for social reading and writing on the Web, it is still very much bound by its technical origins, the blog. This presents significant limitations both in the flexibility of document structures and in the range of media that can be employed in writing and response. Sure, even in the current, ultra-basic version, there’s no reason a CommentPress document can’t incorporate image, video and sound embeds, but they must be fit into the narrow and brittle textual template dictated by the blog.

All of which is to say that we do not view CommentPress or whatever might grow out of it as an end goal but rather as a step along the way. In fact, this and all of the experiments mentioned above were undertaken in large part as field research for Sophie, and they have had a tremendous impact on its development. While there is still much work to be done, the ultimate goal of the Sophie project is to make a tool that handles all the social network interactions (and more) that CommentPress does but within a far more fluid and easy-to-use composition/reading space where media can mix freely. That’s the larger prize. For the moment though, let’s keep hacking the blog to within an inch of its life and seeing what we can discover.

A million thanks go out to our phenomenal corps of first-run testers, particularly Kathleen Fitzpatrick, Karen Schneider, Manan Ahmed, Tom Keays, Luke Rodgers, Peter Brantley and Shana Kimball, for all the thoughtful and technically detailed feedback they’ve showered upon us over the past few days. Thanks to you guys, we’re getting this out of the gate on solid legs and our minds are now churning with ideas for future development.

Here is a chronology of CommentPress projects leading up to the open source release (July 25, 2007):

GAM3R 7H30RY 1.1 by McKenzie Wark (launched May 22, 2006)

The Holy of Holies: On the Constituents of Emptiness by Mitchell Stephens (December 6, 2006)

The Iraq Study Group Report with Lapham’s Quarterly (December 21, 2006)

The President’s Address to the Nation, January 10th, 2007 with Lapham’s Quarterly (together, the Address and the ISG Report comprised Operation Iraqi Quagmire) (January 10, 2007)

The Future of Learning Institutions in a Digital Age with HASTAC (Humanities, Arts, Science, and Technology Advanced Collaboratory) (January 17, 2007)

Scholarly Publishing in the Age of the Internet by Kathleen Fitzpatrick, published at MediaCommons (March 30, 2007)

(All the above are best viewed in Firefox. The new release works in all major browsers and we’re continuing to work on compatibility.)

Author Archives: ben vershbow

cascading phrases

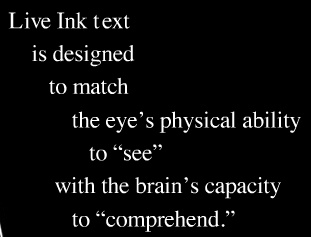

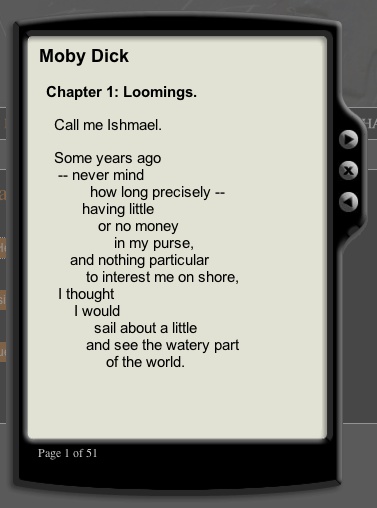

Live Ink is an alternative approach to presenting texts in screen environments, arranging them in series of cascading phrases to increase readability (I saw this a couple of years ago at an educational publishing conference but it was brought to my attention again on Information Aesthetics). Live Ink was developed by brothers Stan and Randall Walker, both medical doctors (Stan an ophthalmologist), who over time became interested in the problems, especially among the young, of reading from computer displays. In their words:

Here’a screenshot of their sample reader with chapter 1 of Moby-Dick:

Thoughts?

edit the galaxy

Galaxiki is “a new kind of wiki based community portal that allows its members to edit stars, planets and moons in a virtual galaxy, creating an entire fictional world online.” The site uses primarily public domain NASA photography.

Millions of stars, planets, moons, pulsars and black holes can be explored using an intuitive 2D map. The site software manages most of the physical properties and behaviours of the solar systems, from orbits to the chemical composition of planetary atmospheres. Some planets offer conditions that may allow life – the idea behind Galaxiki is that community members can create fictional life forms and write about their histories on their planets….For only USD 12.- (or EUR 10.-) you can purchase your own solar system that only you can edit.

darker side of youtube

There’s a good piece in Slate by Nick Douglas, a writer and video blogger out of San Francisco, that casts YouTube as the Hollywood of web video – ?purveyor of bite-sized crap with mass appeal, while the smaller, more innovative “independents” (the Groupers, Vimeos and blip.tvs) struggle in its shadow. YouTube’s dominance, Douglas argues, leads viewers to expect less of a fledgeling cultural arena that could become the leading edge of filmmaking but instead has been made synonymous with shallow, momentary titillation.

Douglas’ critique is on target, and it’s vital to keep questioning the so-called diversity of the mega-aggregators who increasingly dominate the Web, but I wonder whether serious video producers really ought to be looking to YouTube and its competitors as the ultimate venue. As promotional and browsing sites they work well, but a networked, non-Web video client like Miro could be a better forum for challenging work.

the open library

A little while back I was musing on the possibility of a People’s Card Catalog, a public access clearinghouse of information on all the world’s books to rival Google’s gated preserve. Well thanks to the Internet Archive and its offshoot the Open Content Alliance, it looks like we might now have it – ?or at least the initial building blocks. On Monday they launched a demo version of the Open Library, a grand project that aims to build a universally accessible and publicly editable directory of all books: one wiki page per book, integrating publisher and library catalogs, metadata, reader reviews, links to retailers and relevant Web content, and a menu of editions in multiple formats, both digital and print.

A little while back I was musing on the possibility of a People’s Card Catalog, a public access clearinghouse of information on all the world’s books to rival Google’s gated preserve. Well thanks to the Internet Archive and its offshoot the Open Content Alliance, it looks like we might now have it – ?or at least the initial building blocks. On Monday they launched a demo version of the Open Library, a grand project that aims to build a universally accessible and publicly editable directory of all books: one wiki page per book, integrating publisher and library catalogs, metadata, reader reviews, links to retailers and relevant Web content, and a menu of editions in multiple formats, both digital and print.

Imagine a library that collected all the world’s information about all the world’s books and made it available for everyone to view and update. We’re building that library.

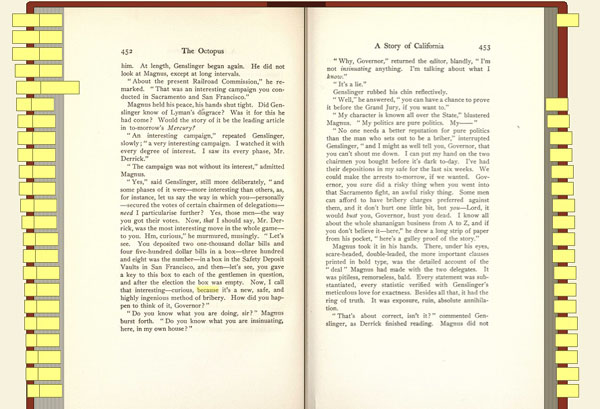

The official opening of Open Library isn’t scheduled till October, but they’ve put out the demo now to prove this is more than vaporware and to solicit feedback and rally support. If all goes well, it’s conceivable that this could become the main destination on the Web for people looking for information in and about books: a Wikipedia for libraries. On presentation of public domain texts, they already have Google beat, even with recent upgrades to the GBS system including a plain text viewing option. The Open Library provides TXT, PDF, DjVu (a high-res visual document browser), and its own custom-built Book Viewer tool, a digital page-flip interface that presents scanned public domain books in facing pages that the reader can leaf through, search and (eventually) magnify.

Page turning interfaces have been something of a fad recently, appearing first in the British Library’s Turning the Pages manuscript preservation program (specifically cited as inspiration for the OL Book Viewer) and later proliferating across all manner of digital magazines, comics and brochures (often through companies that you can pay to convert a PDF into a sexy virtual object complete with drag-able page corners that writhe when tickled with a mouse, and a paper-like rustling sound every time a page is turned).

This sort of reenactment of paper functionality is perhaps too literal, opting for imitation rather than innovation, but it does offer some advantages. Having a fixed frame for reading is a relief in the constantly scrolling space of the Web browser, and there are some decent navigation tools that gesture toward the ways we browse paper. To either side of the open area of a book are thin vertical lines denoting the edges of the surrounding pages. Dragging the mouse over the edges brings up scrolling page numbers in a small pop-up. Clicking on any of these takes you quickly and directly to that part of the book. Searching is also neat. Type a query and the book is suddenly interleaved with yellow tabs, with keywords highlighted on the page, like so:

But nice as this looks, functionality is sacrificed for the sake of fetishism. Sticky tabs are certainly a cool feature, but not when they’re at the expense of a straightforward list of search returns showing keywords in their sentence context. These sorts of references to the feel and functionality of the paper book are no doubt comforting to readers stepping tentatively into the digital library, but there’s something that feels disjointed about reading this way: that this is a representation of a book but not a book itself. It is a book avatar. I’ve never understood the appeal of those Second Life libraries where you must guide your virtual self to a virtual shelf, take hold of the virtual book, and then open it up on a virtual table. This strikes me as a failure of imagination, not to mention tedious. Each action is in a sense done twice: you operate a browser within which you operate a book; you move the hand that moves the hand that moves the page. Is this perhaps one too many layers of mediation to actually be able to process the book’s contents? Don’t get me wrong, the Book Viewer and everything the Open Library is doing is a laudable start (cause for celebration in fact), but in the long run we need interfaces that deal with texts as native digital objects while respecting the originals.

What may be more interesting than any of the technology previews is a longish development document outlining ambitious plans for building the Open Library user interface. This covers everything from metadata standards and wiki templates to tagging and OCR proofreading to search and browsing strategies, plus a well thought-out list of user scenarios. Clearly, they’re thinking very hard about every conceivable element of this project, including the sorts of things we frequently focus on here such as the networked aspects of texts. Acolytes of Ted Nelson will be excited to learn that a transclusion feature is in the works: a tool for embedding passages from texts into other texts that automatically track back to the source (hypertext copy-and-pasting). They’re also thinking about collaborative filtering tools like shared annotations, bookmarking and user-defined collections. All very very good, but it will take time.

Building an open source library catalog is a mammoth undertaking and will rely on millions of hours of volunteer labor, and like Wikipedia it has its fair share of built-in contradictions. Jessamyn West of librarian.net put it succinctly:

It’s a weird juxtaposition, the idea of authority and the idea of a collaborative project that anyone can work on and modify.

But the only realistic alternative may well be the library that Google is building, a proprietary database full of low-quality digital copies, a semi-accessible public domain prohibitively difficult to use or repurpose outside the Google reading room, a balkanized landscape of partner libraries and institutions left in its wake, each clutching their small slice of the digitized pie while the whole belongs only to Google, all of it geared ultimately not to readers, researchers and citizens but to consumers. Construed more broadly to include not just books but web pages, videos, images, maps etc., the Google library is a place built by us but not owned by us. We create and upload much of the content, we hand-make the links and run the search queries that program the Google brain. But all of this is captured and funneled into Google dollars and AdSense. If passive labor can build something so powerful, what might active, voluntary labor be able to achieve? Open Library aims to find out.

outages

Apologies to everyone who has had difficulty viewing our sites today. We’ve determined that the problem lies not with our server but with Time Warner. Apparently, sites are viewable through different ISPs but Time Warner/Roadrunner appears to be undergoing some sort of maintenance that prevents them from resolving our URLs. We thought this might just be a New York problem but recently got a message from someone in North Carolina that they’re experiencing the same thing. If you’re reading this now it probably means you are unaffected.

A paranoid thought did occur to me: is this momentary glitch a preview of a post net neutrality world in which less privileged, non-premium sites like ours get the shaft?

Hopefully this will all pass soon.

Update: it seems to have passed.

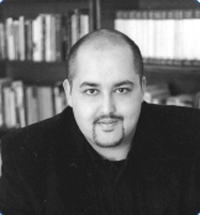

welcome siva vaidhyanathan, our first fellow

We are proud to announce that the brilliant media scholar and critic Siva Vaidhyanathan will be establishing a virtual residency here as the Institute’s first fellow. Siva is in the process of moving from NYU to the University of Virginia, where he’ll be teaching media studies and law. While we’re sad to be losing him in New York, we’re thrilled that this new relationship will bring our work into closer, more dynamic proximity. Precisely what “fellowship” entails will develop over time but for now it means that the Institute is the new digital home of SIVACRACY.NET, Siva’s popular weblog. It also means that next month we will be a launching a new website devoted to Siva’s latest book project, The Googlization of Everything, an examination of Google’s disruptive effects on culture, commerce and community.

We are proud to announce that the brilliant media scholar and critic Siva Vaidhyanathan will be establishing a virtual residency here as the Institute’s first fellow. Siva is in the process of moving from NYU to the University of Virginia, where he’ll be teaching media studies and law. While we’re sad to be losing him in New York, we’re thrilled that this new relationship will bring our work into closer, more dynamic proximity. Precisely what “fellowship” entails will develop over time but for now it means that the Institute is the new digital home of SIVACRACY.NET, Siva’s popular weblog. It also means that next month we will be a launching a new website devoted to Siva’s latest book project, The Googlization of Everything, an examination of Google’s disruptive effects on culture, commerce and community.

Siva is one of just a handful of writers to have leveled a consistent and coherent critique of Google’s expansionist policies, arguing not from the usual kneejerk copyright conservatism that has dominated the debate but from a broader cultural and historical perspective: what does it mean for one company to control so much of the world’s knowledge? Siva recently gave a keynote talk at the New Network Theory conference in Amsterdam where he explored some of these ideas, which you can read about here. Clearly Siva’s views on these issues are sympathetic to our own so we’re very glad to be involved in the development of this important book. Stay tuned for more details.

Welcome aboard, Siva.

perspectives on distributed creativity

Assignment Zero, an experimental news site that brings professional journalists together with volunteer researcher-reporters to collaboratively write stories, has kicked off its tenure at Wired News by doing an extended investigation of “crowdsourcing.” Crowdsourcing is the latest internet parlance used to describe work traditionally carried out by one or a few persons being distributed among many people. I’ve always found something objectionable about the term, which is more suggestive of a business model than a creative strategy and sidesteps the numerous ethical questions about peer production and corporate exploitation that are inevitably bound up in it. But it’s certainly a subject that could use a bit of scrutiny, and who better to do it than a journalistic team composed of the so-called crowd?

It is in this self-reflexive spirt that Jay Rosen, a exceedingly sharp thinker on the future of journalism and executive editor of Assignment Zero (and the related NewAssignment.net), presents an interesting series of features assembled by his “pro-am” team that look at a wide variety of online collaboration forms. This package has been in development for several months (many of the pieces contain links back to the original “assignments” and you can see how they evolved) and there’s a lot there: 80 Q&A’s, essays and stories (mostly Q&A’s) looking at innovative practices and practitioners across media types and cultural/commercial arenas. From an initial sifting, it’s less an analysis than just a big collection of perspectives, but this is valuable I think, if for no other reason than as a jumping-off point for further research.

There are many of the usual suspects like Benkler, Lessig, Jarvis, Shirky, Surowiecki, Wales etc., but as many or more of the pieces venture off the beaten track. There’s a thought-provoking interview with Douglas Rushkoff on open source as a cultural paradigm, some stuff on the Wu Ming fiction collective (which is fascinating), a piece about Sydney Poore, a Wikipedia “super-contributor,” and some coverage of our work, an interview with McKenzie Wark about Gamer Theory and collaborative writing. There’s also an essay by one of the Assignment Zero contributors, Kristin Gorski, synthesizing some of the material gathered on the latter subject: “Creative Crowdwriting: The Open Book.”

All in all this seems like a successful test drive for an experimental group that is still inventing its process. I’m interested to see how it develops with other less “wired” subjects.

of shelves and selves

William Drenttel has a lovely post over on Design Observer about the exquisite information of bookshelves, a meditation spurred by 60 photographs of the library of renowned San Francisco designer, typographer, printer and founder of Greenwood Press Jack Stauffacher. Each image (they were taken by Dennis Letbetter) gives a detailed view of one section of Stauffacher’s shelves, a rare glimpse of one individual’s bibliographic DNA, made browseable as a slideshow (unfortunately, the images are not reassembled at the end to give a full view of the collection).

Early evidence suggests that the impulse toward personal mapping through media won’t abate as we go deeper into the digital. Delicious Library and Library Thing are more or less direct transpositions of physical shelves to the computer environment, the latter with an added social dimension (people meeting through their virtual shelves). More generally, social networking sites from Facebook to MySpace are full of self-signification through shelves, or rather lists, of favorite books, movies and music. Social bookmarking sites too bear traces of identity in the websites people save and tag (the tags themselves are a kind of personal signature). Much of the texture and spatial language of the physical may be lost, a new social terrain has opened up, one which we’re only beginning to understand.

But it’s not as though physical bookshelves haven’t always been social. We arrange books not only for our own conceptual orientation, but to give others who venture into our space a sense of our self (or what we’d like to appear as our self), our distinct intellectual algorithm. Browsing a friend’s thoughtfully arranged shelf is like looking through a lens calibrated to their view of the world, especially when those books have played a crucial role, as in Stauffacher’s, in shaping a life’s work. Drenttel savors the idiosyncrasies that inevitably are etched into such a collection:

I have seen many great rare book libraries…. But the libraries I most enjoy are working libraries, where the books have been used and cited and annotated – first editions marred with underlining, notes throughout their pages. (I will always remember the chaos of Susan Sontag’s library, where every book had been touched, read and filled with notes and ephemera.) The organization of a working library is seldom alphabetical…but rather follows some particular mental construct of its owner. Jack Stauffacher’s shelves have some order, one knows. But it is his order, his life.

Or, in Stauffacher’s own words:

Without this working library, I would have no compass, no map, to guide me through the density of our human condition.

six blind men and an elephant

Thomas Mann, author of The Oxford Guide to Library Research, has published an interesting paper (pdf available) examining the shortcomings of search engines and the continued necessity of librarians as guides for scholarly research. It revolves around the case of a graduate student investigating tribute payments and the Peloponnesian War. A Google search turns up nearly 80,000 web pages and 700 books. An overwhelming retrieval with little in the way of conceptual organization and only the crudest of tools for measuring relevance. But, with the help of the LC Catalog and an electronic reference encyclopedia database, Mann manages to guide the student toward a manageable batch of about a dozen highly germane titles.

Summing up the problem, he recalls a charming old fable from India:

Most researchers – at any level, whether undergraduate or professional – who are moving into any new subject area experience the problem of the fabled Six Blind Men of India who were asked to describe an elephant: one grasped a leg and said “the elephant is like a tree”; one felt the side and said “the elephant is like a wall”; one grasped the tail and said “the elephant is like a rope”; and so on with the tusk (“like a spear”), the trunk (“a hose”) and the ear (“a fan”). Each of them discovered something immediately, but none perceived either the existence or the extent of the other important parts – or how they fit together.

Finding “something quickly,” in each case, proved to be seriously misleading to their overall comprehension of the subject.

In a very similar way, Google searching leaves remote scholars, outside the research library, in just the situation of the Blind Men of India: it hides the existence and the extent of relevant sources on most topics (by overlooking many relevant sources to begin with, and also by burying the good sources that it does find within massive and incomprehensible retrievals). It also does nothing to show the interconnections of the important parts (assuming that the important can be distinguished, to begin with, from the unimportant).

Mann believes that books will usually yield the highest quality returns in scholarly research. A search through a well tended library catalog (controlled vocabularies, strong conceptual categorization) will necessarily produce a smaller, and therefore less overwhelming quantity of returns than a search engine (books do not proliferate at the same rate as web pages). And those returns, pound for pound, are more likely to be of relevance to the topic:

Each of these books is substantially about the tribute payments – i.e., these are not just works that happen to have the keywords “tribute” and “Peloponnesian” somewhere near each other, as in the Google retrieval. They are essentially whole books on the desired topic, because cataloging works on the assumption of “scope-match” coverage – that is, the assigned LC headings strive to indicate the contents of the book as a whole….In focusing on these books immediately, there is no need to wade through hundreds of irrelevant sources that simply mention the desired keywords in passing, or in undesired contexts. The works retrieved under the LC subject heading are thus structural parts of “the elephant” – not insignificant toenails or individual hairs.

If nothing else, this is a good illustration of how libraries, if used properly, can still be much more powerful than search engines. But it’s also interesting as a librarian’s perspective on what makes the book uniquely suited for advanced research. That is: a book is substantial enough to be a “structural part” of a body of knowledge. This idea of “whole books” as rungs on a ladder toward knowing something. Books are a kind of conceptual architecture that, until recently, has been distinctly absent on the Web (though from the beginning certain people and services have endeavored to organize the Web meaningfully). Mann’s study captures the anxiety felt at the prospect of the book’s decline (the great coming blindness), and also the librarian’s understandable dread at having to totally reorganize his/her way of organizing things.

It’s possible, however, to agree with the diagnosis and not the prescription. True, librarians have gotten very good at organizing books over time, but that’s not necessarily how scholarship will be produced in the future. David Weinberg ponders this:

As an argument for maintaining human expertise in manually assembling information into meaningful relationships, this paper is convincing. But it rests on supposing that books will continue to be the locus of worthwhile scholarly information. Suppose more and more scholars move onto the Web and do their thinking in public, in conversation with other scholars? Suppose the Web enables scholarship to outstrip the librarians? Manual assemblages of knowledge would retain their value, but they would no longer provide the authoritative guide. Then we will have either of two results: We will have to rely on “‘lowest common denominator'”and ‘one search box/one size fits all’ searching that positively undermines the requirements of scholarly research”…or we will have to innovate to address the distinct needs of scholars….My money is on the latter.

As I think is mine. Although I would not rule out the possibility of scholars actually participating in the manual assemblage of knowledge. Communities like MediaCommons could to some extent become their own libraries, vetting and tagging a wide array of electronic resources, developing their own customized search frameworks.

There’s much more in this paper than I’ve discussed, including a lengthy treatment of folksonomies (Mann sees them as a valuable supplement but not a substitute for controlled taxonomies). Generally speaking, his articulation of the big challenges facing scholarly search and librarianship in the digital age are well worth the read, although I would argue with some of the conclusions.