Microsoft Multimedia Schubert was published fifteen years ago, in 1993. Developed by the Voyager Company, the program was one of many in an early “Microsoft Multimedia Catalog.” It allows users to engage in a close reading of Schubert’s Trout Quintet, illuminated with Alan Rich’s moment-by-moment commentary. Rendered in text, Rich’s comments are programmed to appear at specific instances during each movement.

Though such multimedia CD-ROMs are commonplace by today’s standards, MS Schubert and its ilk came at a time when designers were seriously rethinking what was possible in the realm of multimedia. There’s much to learn from their spirit of innovation.

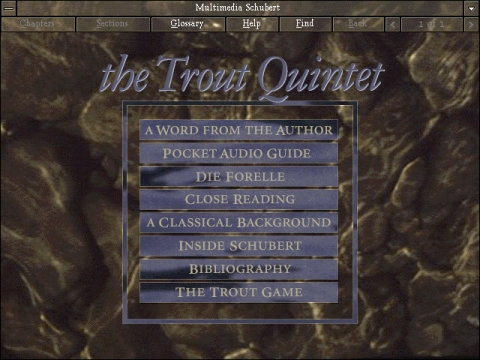

For instance, Voyager, Rich and co. flesh out their disc with a glossary of musical taxonomy, a brief history of the sonata form, and encyclopedic accounts of Schubert’s life and work; there’s even a modest Schubert game, in which listeners attempt to identify randomly-generated audio fragments of the Trout Quintet. (My high score: zero.) All in all, I think the CD-ROM constitutes an elegant combination of aural, textual and visual elements. It’s an inspired precursor to more comprehensive CD-ROM encyclopedias like Encarta, and its close reading is still valuable today. Not too shabby, for ’93.

Obviously, the intervening years have seen enormous advancements in computing and the rise of the Web, which could give the Schubert multimedia suite a new lease on life. In the coming months, we’ll ask scholars and musicians what they want out of a multimodal close reading, and how a new generation of electronic books can serve those needs. How can we abet in-depth listening and foster a discussion of music’s nuances? For that matter, which musicians and works ought to be included in an initial library of close readings, and who (if anyone) should lead them?

Of course, not every ’90s idea was an earth-shattering success, but there are lessons in the failures. In 1995, for instance, Microsoft debuted its oft-derided Bob operating system, which immersed novices in a house-like virtual environment where program icons took the form of everyday domestic objects: shelved books, rolodexes, bank ledgers left on coffee tables. Was it horrendously executed and functionally flawed? Yes. Tacky, juvenile? Those, too. But the Bob OS was also giddy with multimedia possibility – it was a dicey proposition in an industry with damn too few of them. See for yourself:

The thought of spending my days in Bob’s syrupy universe is a frightening one. But I wonder: did it flop because of its gung-ho cuteness, or because of its experimental premise?

It’s crucial, I feel, to approach our new projects with the “what if…?” mentality that reigned, however briefly, in early-’90s projects like Schubert and Bob. The latter bombed, yeah, but it was a well-intentioned failure. In some ways, it attempted to change how operating systems should look, feel and perform – even if those attempts were half-hearted and immediately superseded by Windows 95.

As the norms of our gadget-usage continue to cement themselves, it’s going to get harder and harder to abandon our preconceptions of what multimedia can accomplish, i.e., of how stuff should work. In revitalizing and updating projects like Schubert, we have a perfect opportunity to learn from the past: what it got right, what it botched abysmally, and its wide-eyed awe as to the future’s potential.

I’d love to find where I can have access to those CD Companions in a fashion that will work on Leopard. Particularly Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring.