Buckle your seatbelts, we may be experiencing a bit of turbulence. We’re in the process of migrating our server from Los Angeles, where for the past three and a half years it has resided, at the University of Southern California, to our home town of New York. Our ties to USC remain strong and will continue, but we’re currently forging an exciting new relationship in NYC and so have decided to move our technical operations here. More details on this soon.

For now, this means that we may be going a day or two here on if:book without new posts. And, due to minor complications in the switchover process, it also means we could experience a few hours of total site outage (crossing our fingers that this can be avoided). At any rate, if:book and the rest of the Institute’s sites will be soon be running smoothly again from a little box in the big apple. Bear with us as we settle into our new digs.

Monthly Archives: March 2008

friday musings on the literary

Faber chief executive Stephen Page’s article in yesterday’s Guardian outlines some straightforward ways of taking advantage of social media, on-demand business models and so on in the interests of sustaining Faber into the 21st century. Push out content that brings people back to your core product; build communities; leverage print on demand. All fairly basic stuff.

But the comments are intriguing. Granted, Comment Is Free for some reason attracts exceptionally bellicose commenters; but even so the juxtaposition of Faber, a bastion of traditional highbrow literature, with its associations of TS Eliot and the ‘aristocracy of culture’, with the digital space, has prompted howls of derision entirely out of proportion to the relatively moderate statements in Page’s piece.

The idea of using the Web – which, notwithstanding its roots in the military, has a strong bottom-up ideology – to further good old-fashioned ‘high culture’ is horrifying to one commenter: “Why must *YOU* be the one to create that additional content, when heretofore that content has been (relatively) independently produced? Because you need to control opinion and dictate what the reading public is told about?”. To another, Page’s attempts to harness the Web for old-fashioned publishing is doomed, because the internet’s culture of sharing – via Project Gutenberg and elsewhere – will eventually mean that all books are free.

It seems as though the great commenting public wants it all ways. Faber is an intellectually-snobbish establishment and must give way before the bottom-up populism of digital content. Publishing should keep its grubby corporate hands off the purity of the internet’s gift economy. Serious books are found only in independent booksellers. ‘Serious writers’ use the Web nowadays. The print book is doomed anyway. The print book will always exist. And so on.

What strikes me is that all these points are being muddled and thrown at the same article – often with little discernible reference to the thrust of the piece – because ‘quality writing’ is a cultural space where different kinds of internet use overlap. The Web is both a means of publishing content, and also a means of promoting content published in other media. But in the discourse of books and the internet the two are often talked about in the same breath, connected – or separated – by debates about quality, democracy and so on.

Page laments about the rise of the mass market, and the burying of ‘serious’ writing ‘under a pile of celebrity biography, cookery and misery memoir’. But the ideology of ‘the literary’ – gestured at in Page’s resolutely highbrow stance – is firmly connected to the tradition of print. Page does not envision a culture mediated solely through the Web, but rather a avision of ‘global communities’ finding niche interests and sourcing the books that nourish them, cheating the mass market of its final victory over ‘serious’ culture:

I am not an advocate of the life led online, but as broadband reaches all generations, genders and income brackets, so this will develop usefully. It won’t be all of life but it must be a place where niche interests can develop, robbing the mass market of a portion of its control. Literature can thrive in these places.

So publishers must harness the great power of online networks through enriching reader experience. We must provide content that can be searched and browsed, and create extra materials – interviews, podcasts and the like. We mustn’t be afraid of inviting readers to be involved. Beyond online retailing, publishers can now build powerful online places to showcase their books through their own and others’ websites and build communities around their own areas of particular interest and do so with writers.

‘Literature’ here evokes a well-rooted (if not always clearly-defined) ideology. When I say ‘literary’ I mean things fitting a loose cluster of – sometimes self-contradictory – ideas including, but not limited to:

the importance of traceable authorship

the value of ‘proper’ language

the idea that some kinds of writing are better than others

that some kinds of publishing are better than others

that there is a hierarchy of literary quality

And so on. If examined too closely, these ideas tend to complicate and undermine one another, always just beyond the grasp. But they endure. And they remain close to the core of why many people write. Write, as an intransitive verb (Barthes), because another component of the ideology of ‘literary’ is that it’s a broadcast-only model. If you don’t believe me, check out any writers’ community and see how much keener would-be Authors are to post their own work than to critique or review that of others. ‘Literary’ works talk to one another, across generations, but authors talk to readers and readers don’t – or at least have never been expected – to talk back. (Feel free, by the way, to roll your own version of this nexus, or to disagree with mine. One of the reasons it’s so pervasive as a set of ideas is because it’s so damn slippery.)

Recently, in our Arts Council research, Chris and I have interviewed writers, magazines, publishers and proponents of countless other types of literary activity. And it’s clear that the writerly world uses the Web in two distinct ways. Firstly, it is – as Page’s article describes – an effective way of promoting or streamlining literary activity that is not intrinsically digital. A good example might be the way in which online zines function as a front-line filter for new writing – as it were the widest-mesh filter for literary quality – and for many is often the first taste of publishing.

People use the Web to share work, peer-review their writing, promote activities, sell books and find others with the same interests. But this activity happens almost always with reference to the ideology of the literary – in particular, to the aspirational associations of broadcast-only, hard-copy-printed, selected-and-paid-for-and-edited-by-someone-else-and-hopefully-bought-and-read-by-the-public publication. For those submitting to such magazines, the hope is that they will move up the literary food chain, get published in better known journals, and perhaps – the holy grail – finally after decades of grim and impecunious slogging, be anthologized by Faber.

But while the majority of ‘literary’ activity online is of this sort, defined always implicitly in relation to the painful journey towards selection for the ultimate validation of print publication, the vast majority of writing online is not. For starters, most of it doesn’t self-identify as ‘creative’: it’s informational, discursive, conversational and ephemeral. Then the Web encourages collaborative writing, interrogating the idea of individual voice. Fan fiction, with its lack of interest in ‘originality’, peer-to-peer social structures and cheerfully hedonic attitude interrogates the idea of ‘originality’. Collaborative writing technologies interrogate the idea of authorship; 1337 interrogates ‘proper’ writing. I have yet to find a collaborative writing platform (try Protagonize, 1000000monkeys or ficlets if you like) that’s produced a story I want to reread for its own sake. Ben has written recently on how ‘boring’ he finds hypertext. The skittish and innovation-hungry blogosphere, while increasingly a source of books is not in terms of the output most natural to it ‘literary’ in any sense that bears any relation to tradition of such. And when stories are told in a form that makes best use of the internet’s boundless, unreliable, multi-platform qualities – think of an alternate reality game – this bears little resemblance to anything that could be assessed in such terms either.

I’m aware that all this could easily be read either as a dismissal of the cultural value of the Web, or else as a call to the world of literature to get back in its box. But I mean neither of those things. What I do want to suggest, though, is that it’s not enough to murmur soothingly about how Web is a young form, and that it’ll take a while for ‘great writers’ to emerge. Rather, it strikes me that the ideology of ‘the literary’ – including that of ‘great writers’ – is profoundly bound to the physical form of books, and to pretend otherwise is to misunderstand the Web.

Obviously plenty of print books have no literary value. But the ideology of ‘literary’ is inseparable from print. Authorship is necessary and value-laden at least partly because with no authorship there’s no copyright, and no-one gets paid. The novel packs a massive cultural punch – but arguably 60,000 words just happens to make a book that is long enough to sell for a decent price but short enough to turn out reasonably cheaply. Challenge authorship, remove formal constraints – or create new ones: as O’Reilly’s guides to creating appealing web content will tell you, your online readership is more likely to lose interest if asked to scroll below the fold. Will the forms stay the same? My money says they won’t. And hence much of what’s reified as ‘literary’, online, ceases to carry much weight.

So net-savvy proponents of ‘literary’ stuff aren’t trying to use the Web as a delivery mechanism. Why would you, when there are so many other things it’s useful for? Tom Chivers, live poetry promoter and organizer of the London Word Festival, estimates that he spends a third to half of his time as a promoter on online community-building activities. But the ‘literary’ stuff that he’s organizing happens elsewhere; his online activity is vital to promoting his work, but is not the work itself. Similarly, I spent a fascinating hour or so this afternoon talking to Joe Dunthorne, who told me that he was spurred to complete his novel Submarine by the enthusiastic popular response that first drafts of the initial material generated on writers’ community ABCTales – an intriguingly twenty-first century way to find the validation you need to push your writing career forward. Tom and Joe are both in their twenties, passionate about writing and confidently net-native. Both use the Web in a way that supports their literary interests. But neither sees the Web as a suitable format for ‘final’ publication.

This isn’t to suggest that there’s no room for ‘the literary’ online. Finding new writers; building a community to peer-review drafts; promoting work; pushing out content to draw people back to a publisher’s site to buy books. All these make sense, and present huge opportunities for savvy players. But – and here I realise that this all may be just a (rather lengthy) footnote to Ben’s recent piece on Hypertextopia – to attempt to transplant the ideology of the literary onto the Web will fail unless it is done with reference to the print culture that produced it. Otherwise the work will, by literary standards, be judged second-rate, while by geek standards it’ll seem top-down, limited and static. Or just boring.

I’ll be interested to see how Faber approaches online community-building. Done well, here’s no reason why it shouldn’t help shift books. But while it might help shift books, or be used to reproduce or share books, the Web is fundamentally other to the philosophy that produces books. Anyone serious about using the Web on its own terms as a delivery mechanism for artistic material needs to abandon print-determined criteria for evaluating quality – literary values – and investigate what the medium is really good for.

nicholson baker on the charms of wikipedia

I finally got around to reading Nicholson Baker’s essay in the New York Review of Books, “The Charms of Wikipedia,” and it’s… charming. Baker has a flair for idiosyncratic detail, which makes him a particularly perceptive and entertaining guide through the social and procedural byways of the Wikipedia mole hill. Of particular interest are his delvings into the early Wikipedia’s reliance on public domain reference works, most notably the famous 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica: “The fragments from original sources persist like those stony bits of classical buildings incorporated in a medieval wall.”

Baker also has some smart things to say on the subject of vandalism:

Wikipedians see vandalism as a problem, and it certainly can be, but a Diogenes-minded observer would submit that Wikipedia would never have been the prodigious success it has been without its demons.

This is a reference book that can suddenly go nasty on you. Who knows whether, when you look up Harvard’s one-time warrior-president, James Bryant Conant, you’re going to get a bland, evenhanded article about him, or whether the whole page will read (as it did for seventeen minutes on April 26, 2006): “HES A BIG STUPID HEAD.” James Conant was, after all, in some important ways, a big stupid head. He was studiously anti-Semitic, a strong believer in wonder-weapons – ?a man who was quite as happy figuring out new ways to kill people as he was administering a great university. Without the kooks and the insulters and the spray-can taggers, Wikipedia would just be the most useful encyclopedia ever made. Instead it’s a fast-paced game of paintball.

Not only does Wikipedia need its vandals – ?up to a point – ?the vandals need an orderly Wikipedia, too. Without order, their culture-jamming lacks a context. If Wikipedia were rendered entirely chaotic and obscene, there would be no joy in, for example, replacing some of the article on Archimedes with this:

Archimedes is dead.

He died.

Other people will also die.

All hail chickens.

The Power Rangers say “Hi”

The End.

Even the interesting article on culture jamming has been hit a few times: “Culture jamming,” it said in May 2007, “is the act of jamming tons of cultures into 1 extremely hot room.”

critical perspectives on web 2.0

First Monday has a new special issue out devoted to unpacking the politics, economics and ethics of Web 2.0. Looks like lots of interesting stuff. From the preface by Michael Zimmer:

Web 2.0 represents a blurring of the boundaries between Web users and producers, consumption and participation, authority and amateurism, play and work, data and the network, reality and virtuality. The rhetoric surrounding Web 2.0 infrastructures presents certain cultural claims about media, identity, and technology. It suggests that everyone can and should use new Internet technologies to organize and share information, to interact within communities, and to express oneself. It promises to empower creativity, to democratize media production, and to celebrate the individual while also relishing the power of collaboration and social networks.

But Web 2.0 also embodies a set of unintended consequences, including the increased flow of personal information across networks, the diffusion of one’s identity across fractured spaces, the emergence of powerful tools for peer surveillance, the exploitation of free labor for commercial gain, and the fear of increased corporatization of online social and collaborative spaces and outputs.

In Technopoly, Neil Postman warned that we tend to be “surrounded by the wondrous effects of machines and are encouraged to ignore the ideas embedded in them. Which means we become blind to the ideological meaning of our technologies” [1]. As the power and ubiquity of Web 2.0 rises, it becomes increasingly difficult for users to recognize its externalities, and easier to take the design of such tools simply “at interface value” [2]. Heeding Postman and Turkle’s warnings, this collection of articles will work to remove the blinders of the unintended consequences of Web 2.0’s blurring of boundaries and critically explore the social, political, and ethical dimensions of Web 2.0.

flight paths 2.0

Back in December we announced the launch of Flight Paths, a “networked novel” that is currently being written by Kate Pullinger and Chris Joseph with feedback and contributions from readers. At that point, the Web presence for the project was a simple CommentPress blog where readers could post stories, images, multimedia and links, and weigh in on the drafting of terms and conditions for participation. Since then, Kate and Chris have been working on setting up a more flexible curatorial environment, and just this week they unveiled a lovely new Flight Paths site made in Netvibes.

Netvibes is a web-based application (still in beta) that allows you to build personalized start pages composed of widgets and modules which funnel in content from various data sources around the net (think My Yahoo! or iGoogle but with much more ability to customize). This is a great tool to try out for a project that is being composed partly out of threads and media fragments from around the Web. The blog is still embedded as a central element, and is still the primary place for reader-collaborators to contribute, but there are now several new galleries where reader-submitted works can be featured and explored. It’s a great new platform and an inventive solution to one of CommentPress’s present problems: that it’s good at gathering content but not terribly good at presenting it. Take a look, and please participate if you feel inspired.

Multimedia gallery on the new Flight Paths site

hypertextopia

We were recently alerted, via Grand Text Auto, to a new hypertext fiction environment on the Web called Hypertextopia:

Hypertextopia is a space where you can read and write stories for the internet. On the surface, it looks like a mind-map, but it embeds a word-processor, and allows you to publish your stories like a blog.

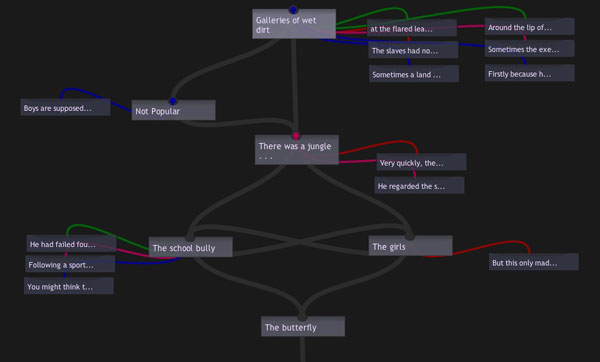

The site is gorgeously done, applying a fresh coat of Web 2.0 paint to the creaky concepts of classical hypertext. I find myself strangely conflicted, though, as I browse through it. Design-wise, it is a triumph, and really gets my wheels spinning w/r/t the possibilities of online writing systems. The authoring tools they’ve developed are simple and elegant, allowing you to write “axial hypertexts”: narratives with a clear beginning and end but with multiple pathways and digressions in between. You read them as a series of textual screens, which can include beautiful fold-out boxes for annotations and illustrations, and various color-coded links (the colors denote different types of internal links, which the author describes). You also have the option of viewing stories as nodal maps, which show the story’s underlying structure. This is part of the map of “The Butterfly Boy” by William Vollmann (by all indications, the William Vollmann):

Lovely as it all is though, it doesn’t convince me that hypertext is any more viable a literary form now, on the Web, than it was back in the heyday of Eastgate and Storyspace. Outside its inner circle of devotees, hypertext has always been more interesting in concept than in practice. A necessary thought experiment on narrative’s deconstruction in a post-book future, but not the sort of thing you’d want to read for pleasure.

It’s always felt to me like a too-literal reenactment of Jorge Luis Borges’ explosion of narrative in The Garden of Forking Paths. In the story, the central character, a Chinese double agent in WWI being pursued by a British assassin who has learned of his treachery, recalls a lost, unfinished novel written by a distant ancestor. It is an infinte story that encompasses every possible event and outcome for its characters: a labyrinth, not in space but in time. Borges meant the novel not as a prescription for a new literary form but as a metaphor of parallel worlds, yet many have cited this story as among the conceptual forebears of hypertext fiction, and Borges is much revered generally among technophiles for writing fables that eerily prefigure the digital age.

I’ve always found it odd how people (techies especially) seem to get romantic (perhaps fetishistic is the better word) about Borges. Prophetic he no doubt was, but his tidings are dark ones. Tales like “Forking Paths,” Funes the Memorious and The Library of Babel are ideas taken to a frightening extreme, certainly not things we would wish to come true. There are days when the Internet does indeed feel a bit like the Library of Babel, a place where an infinity of information has led to the death of meaning. But those are the days I wish we could put the net back in the box and forget it ever happened. I get a bit of that feeling with literary hypertext -? insofar as it reifies the theoretical notion of the death of the author, it is not necessarily doing the reader any favors.

Hypertext’s main offense is that it is boring, in the same way that Choose Your Own Adventure stories are fundamentally boring. I know that I’m meant to feel liberated by my increased agency as reader, but instead I feel burdened. What are offered as choices -? possible pathways though the maze -? soon start to weigh like chores. It feels like a gimmick, a cheap trick, like it doesn’t really matter which way you go (that the prose tends to be poor doesn’t help). There’s a reason hypertext never found an audience.

I can, however, see the appeal of hypertext fictions as puzzles or games. In fact, this may be their true significance in the evolution of storytelling (and perhaps why I don’t get them, because I’m not a gamer). Thought of this way, it’s more about the experience of navigating a narrative landscape than the narrative itself. The story is a sort of alibi, a pretext, for engaging with a particular kind of form, a form which bears far more resemblance to a game than to any kind of prose fiction predecessor. That, at any rate, is how I’ve chosen to situate hypertext. To me, it’s a napkin sketch of a genuinely new form -? video games -? that has little directly to do with writing or reading in the traditional sense. Hypertext was not the true garden of forking paths (which we would never truly want anyway), but a small box of finite options. To sift through them dutifully was about as fun as the lab rat’s journey through the maze. You need a bigger algorithmic engine and the sensory fascinations of graphics (and probably a larger pool of authors and co-creators too) to generate a topography vast enough to hide, at least for a while, its finiteness -? long enough to feel mysterious. That’s what games do, and do well.

I’m sure this isn’t an original observation, but it’s baggage I felt like unloading since classical hypertext is a topic we’ve largely skirted around here at the Institute. Grumbling aside though, Hypertextopia offers much to ponder. Recontextualizing a pre-Web form in the Web is a worthwhile experiment and is bound to shed some light. I’m thinking about how we might play around in it…