I’ve been reading failed Web1.0 entrepreneur Andrew Keen’s The Cult of the Amateur. For those who haven’t hurled it out of the window already, this is a vitriolic denouncement of the ways in which Web2.0 technology is supplanting ‘expert’ cultural agents with poor-quality ‘amateur’ content, and how this is destroying our culture.

In vehemence (if, perhaps, not in eloquence), Keen’s philippic reminded me of Alexander Pope (1688-1744). Pope was one of the first writers to popularize the notion of a ‘critic’ – and also, significantly, one of the first to make an independent living through sales of his own copyrighted works. There are some intriguing similarities in their complaints.

In the Dunciad Variorum (1738), a lengthy poem responding to the recent print boom with parodies of poor writers, information overload and a babble of voices (sound familiar, anyone?) Pope writes of ‘Martinus Scriblerus’, the supposed author of the work

He lived in those days, when (after providence had permitted the Invention of Printing as a scourge for the Sins of the learned) Paper also became so cheap, and printers so numerous, that a deluge of authors cover’d the land: Whereby not only the peace of the honest unwriting subject was daily molested, but unmerciful demands were made of his applause, yea of his money, by such as would neither earn the one, or deserve the other.

The shattered ‘peace of the honest unwriting subject’, lamented by Pope in the eighteenth century when faced with a boom in printed words, is echoed by Keen when he complains that “the Web2.0 gives us is an infinitely fragmented culture in which we are hopelessly lost as to how to focus our attention and spend our limited time.” Bemoaning our gullibility, Keen wants us to return to an imagined prelapsarian state in which we dutifully consume work that has been as “professionally selected, edited and published”.

In Keen’s ideal, this selection, editing and publication ought (one presumes) to left in the hands of ‘proper’ critics – whose aesthetic in many ways still owes much to (to name but a few) Pope’s Essay On Criticism (1711), or the satirical work The Art of Sinking In Poetry (1727). But faith in these critics is collapsing. Instead, new tools that enable books to be linked give us “a hypertextual confusion of unedited, unreadable rubbish”, while publish-on-demand services swamp us in “a tidal wave of amateurish work”.

So what? you might ask. So the first explosion in the volume of published text created some of the same anxieties as this current one. But this isn’t a narrative of relentless evolutionary progress towards a utopia where everything is written, linked and searchable. The two events don’t exist on a linear trajectory; the links between Pope’s critical writings and Keen’s Canute-like protest against Web2.0 are more complex than that.

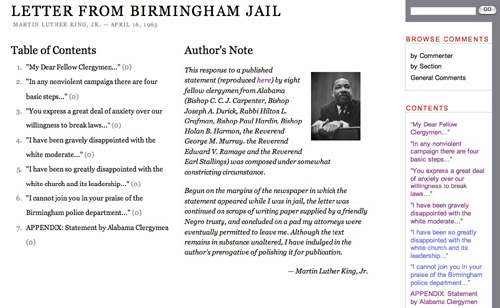

Pope’s response to the print boom was not simply to wish things could return to their previous state; rather, he popularized a critical vocabulary that both helped others to deal with it, and also – conveniently – positioned himself at the tip of the writerly hierarchy. His extensive critical writings, promoting the notions of ‘high’ and ‘low’ quality writing and lambasting the less talented, served to position Pope himself as an expert. It is no coincidence that he was one of the first writers to break free of the literary patronage model and make a living out of selling his published works. The print boom that he critiqued so scatologically was the same boom that helped him to the economic independence that enabled him to criticize as he saw fit.

But where Pope’s approach to the print boom was critical engagement, Keen offers only nostalgic blustering. Where Pope was crucial in developing a language with which to deal with the print boom, Keen wishes only to preserve Pope’s approach. So, while you can choose to read the two voices, some three centuries apart, as part of a linear evolution, it’s also possible to see them as bookends (ahem) to the beginning and end of a literary era.

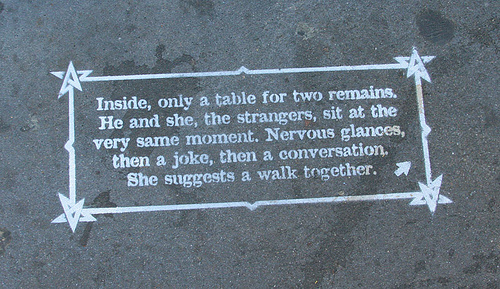

This era is characterized by a conceptual and practical nexus that shackles together copyright, authorship and a homogenized discourse (or ‘common high culture’, as Keen has it), delivers it through top-down and semi-monopolistic channels, and proposes always a hierarchy therein whilst tending ever more towards proliferating mass culture. In this ecology, copyright, elitism and mass populism form inseparable aspects of the same activity: publications and, by extension, writers, all busy ‘molesting’ the ‘peace of the honest unwriting subject’ with competing demands on ‘his applause, yea [on] his money’.

The grading of writing by quality – the invention of a ‘high culture’ not merely determined by whichever ruler chose to praise a piece – is inextricable from the birth of the literary marketplace, new opportunities as a writer to turn oneself into a brand. In a word, the notion of ‘high culture’ is intimately bound up in the until-recently-uncontested economics of survival as a writer.

Again, so what? Well, if Keen is right and the new Web2.0 is undermining ‘high culture’, it is interesting to speculate whether this is the case because it is undermining writers’ established business model, or whether the business model is suffering because the ‘high’ concept is tottering. Either way, if Keen should be lambasted for anything it is not his puerile prose style, or for taking a stand against the often queasy techno-utopianism of some of Web2.0’s champions, but because he has, to date, demonstrated little of Pope’s nous in positioning himself to take advantage of the new economics of publishing.

Others have been more wily, though, in working out exactly what these economics might be. While researching this piece, I emailed Chris Anderson, Wired editor, Long Tail author, sometime sparring partner for Keen and vocal proponent of new, post-digital business models for writers. He told me that

“For what I do speaking is about 10x more lucrative than selling books […]. For me, it would make sense to give away the book to market my personal appearances, much as bands give away their music on MySpace to market their concerts. Thus the title of my next book, FREE, which we will try to give away in every way possible.”

Thus, for Anderson, there is life beyond copyright. It just doesn’t work the same way. And while Keen claims that Web2.0 is turning us into “a nation so digitally fragmented it’s no longer capable of informed debate” – or, in other words, that we have abandoned shared discourse and the respected authorities that arbitrate it in favor of a mulch of cultural white noise, it’s worth noting that Anderson is an example of an authority that has emerged from within this white noise. And who is making a decent living as such.

Anderson did acknowledge, though, that this might not apply to every kind of writer – “it’s just that my particular speaking niche is much in demand these days”. Anderson’s approach is all very well for ‘Big Ideas’ writers; but what, one wonders, is a poet supposed to do? A playwright? My previous post gives an example of just such a writer, though Doctorow’s podcast touches only briefly on the economics of fiction in a free-distribution model. I’ve argued elsewhere that ‘fiction’ is a complex concept and severely in need of a rethink in the context of the Web; my hunch is that while for nonfiction writers the Web requires an adjustment of distribution channels and little more, or creative work – stories – the implications are much more drastic.

I have this suspicion that, for poets and storytellers, the price of leaving copyright behind is that ‘high art’ goes with it. And, further, that perhaps that’s not as terrible as the Keens of this world might think. But that’s another article.