The novelist Jonathan Lethem has been on a most unusual book tour, promoting and selling his latest novel and at the same time publicly questioning the copyright system that guarantees his livelihood. Intellectual property is a central theme in his new book, You Don’t Love Me Yet, which chronicles a struggling California rock band who, in the course of trying to compose and record a debut album, progressively lose track of who wrote their songs. Lethem has always been obsessed with laying bare his influences (he has a book of essays devoted in large part to that), but this new novel, which seems on the whole to be a slighter work than his previous two Brooklyn-based sagas, is his most direct stab to date at the complex question of originality in art.

The novelist Jonathan Lethem has been on a most unusual book tour, promoting and selling his latest novel and at the same time publicly questioning the copyright system that guarantees his livelihood. Intellectual property is a central theme in his new book, You Don’t Love Me Yet, which chronicles a struggling California rock band who, in the course of trying to compose and record a debut album, progressively lose track of who wrote their songs. Lethem has always been obsessed with laying bare his influences (he has a book of essays devoted in large part to that), but this new novel, which seems on the whole to be a slighter work than his previous two Brooklyn-based sagas, is his most direct stab to date at the complex question of originality in art.

In February Lethem published one of the better pieces that has been written lately about the adverse effects of our bloated copyright system, an essay in Harper’s entitled “The Ecstasy of Influence,” which he billed provocatively as “a plagiarism.” Lethem’s flippancy with the word is deliberate. He wants to initiate a discussion about what he sees as the ultimately paradoxical idea of owning culture. Lethem is not arguing for an abolition of copyright laws. He still wants to earn his bread as a writer. But he advocates a general relaxation of a system that has clearly grown counter to the public interest.

None of these arguments are particularly new but Lethem reposes them deftly, interweaving a diverse playlist of references and quotations from greater authorities from with the facility of a DJ. And by foregrounding the act of sampling, the essay actually enacts its central thesis: that all creativity is built on the creativity of others. We’ve talked a great deal here on if:book about the role of the writer evolving into something more like that of a curator or editor. Lethem’s essay, though hardly the first piece of writing to draw heavily from other sources, demonstrates how a curatorial method of writing does not necessarily come at the expense of a distinct authorial voice.

The Harper’s piece has made the rounds both online and off and, with the new novel, seems to have propelled Lethem, at least for the moment, into the upper ranks of copyright reform advocates. Yesterday The Washington Post ran a story on Lethem’s recent provocations. Here too is a 50-minute talk from the Authors@Google series (not surprisingly, Google is happy to lend some bandwidth to these ideas).

For some time, Cory Doctorow has been the leading voice among fiction writers for a scaling back of IP laws. It’s good now to see a novelist with more mainstream appeal stepping into the debate, with the possibility of moving it beyond the usual techno-centric channels and into the larger public sphere. I suspect Lethem’s interest will eventually move on to other things (and I don’t see him giving away free electronic versions of his books anytime soon), but for now, we’re fortunate to have his pen in the service of this cause.

Monthly Archives: May 2007

of babies and bathwater

The open-sided, many-voiced nature of the Web lends itself easily to talk of free, collaborative, open-source, open-access. Suddenly a brave new world of open knowledge seems just around the corner. But understandings of how to make this world work practically for imaginative work – I mean written stories – are still in their infancy. It’s tempting to see a clash of paradigms – open-source versus proprietary content – that is threatening the fundamental terms within which all writers are encouraged to think of themselves – not to mention the established business model for survival as such.

The idea that ‘high art’ requires a business model at all has been obscured for some time (in literature at least) by a rhetoric of cultural value. This is the argument offered by many within the print publishing industry to justify its continued existence. Good work is vital to culture; it’s always the creation of a single organising consciousness; and it deserves remuneration. But the Web undermines this: if every word online is infinitely reproducible and editable, putting words in a particular order and expecting to make your living by charging access to them is considerably less effective than it was in a print universe as a model for making a living.

But while the Web erodes the opportunities to make a living as an artist producing patented content, it’s not yet clear how it proposes to feed writers who don’t copyright their work. A few are experimenting with new balances between royalty sales and other kinds of income: Cory Doctorow gives away his books online for free, and makes money of the sale of print copies. Nonfiction writers such as Chris Anderson often treat the book as a trailer for their idea, and make their actual money from consultancy and public speaking. But it’s far from clear how this could work in a widespread way for net-native content, and particularly for imaginative work.

This quality of the networked space also has implications for ideas of what constitutes ‘good work’. Ultimately, when people talk of ‘cultural value’, they usually mean the role that narratives play in shaping our sense of who and what we are. Arguably this is independent of delivery mechanisms, theories of authorship, and the practical economics of survival as an artist: it’s a function of human culture to tell stories about ourselves. And even if they end up writing chick-lit or porn to pay the bills, most writers start out recognising this and wanting to change the world through stories. But how is one to pursue this in the networked environment, where you can’t patent your words, and where collaboration is indispensable to others’ engagement with your work? What if you don’t want anyone else interfering in your story? What if others’ contributions are rubbish?

Because the truth is that some kinds of participation really don’t produce shining work. The terms on which open-source technology is beginning to make inroads into the mainstream – ie that it works – don’t hold so well for open-source writing to date. The World Without Oil ARG in some ways illustrates this problem. When I heard about the game I wrote enthusiastically about the potential I saw in it for and imaginative engagement with huge issues through a kind of distributed creativity. But Ben and I were discussing this earlier, and concluded that it’s just not working. For all I know it’s having a powerful impact on its players; but to my mind the power of stories lies in their ability to distil and heighten our sense of what’s real into an imaginative shorthand. And on that level I’ve been underwhelmed by WWO. The mass-writing experiment going on there tends less towards distillation into memorable chunks of meme and more towards a kind of issues-driven proliferation of micro-stories that’s all but abandoned the drive of narrative in favour of a rather heavy didactic exercise.

So open-sourcing your fictional world can create quality issues. Abandoning the idea of a single author can likewise leave your story a little flat. Ficlets is another experiment that foregrounds collaboration at the expense of quality. The site allows anyone to write a story of no more than (for some reason) 1,024 characters, and publish it through the site. Users can then write a prequel or sequel, and those visiting the site can rate the stories as they develop. It’s a sweetly egalitarian concept, and I’m intrigued by the idea of using Web2 ‘Hot Or Not?’ technology to drive good writing up the chart. But – perhaps because there’s not a vast amount of traffic – I find it hard to spend more than a few minutes at a time there browsing what on the whole feels like a game of Consequences, just without the joyful silliness.

In a similar vein, I’ve been involved in a collaborative writing experiment with OpenDemocracy in the last few weeks, in which a set of writers were given a theme and invited to contribute one paragraph each, in turn, to a story with a common them. It’s been interesting, but the result is sorely missing the attentions of at the very least a patient and despotic editor.

This is visible in a more extreme form in the wiki-novel experiment A Million Penguins. Ben’s already said plenty about this, so I won’t elaborate; but the attempt, in a blank wiki, to invite ‘collective intelligence’ to write a novel failed so spectacularly to create an intelligible story that there are no doubt many for whom it proves the unviability of collaborative creativity in general and, by extension, the necessity of protecting existing notions of authorship simply for the sake of culture.

So if the Web invites us to explore other methods of creating and sharing memetic code, it hasn’t figured out the right practice for creating really absorbing stuff yet. It’s likely there’s no one magic recipe; my hunch is that there’s a meta-code of social structures around collaborative writing that are emerging gradually, but that haven’t formalised yet because the space is still so young. But while a million (Linux) penguins haven’t yet written the works of Shakespeare, it’s too early to declare that participative creativity can only happen at the expense of quality .

As is doubtless plain, I’m squarely on the side of open-source, both in technological terms and in terms of memetic or cultural code. Enclosure of cultural code (archetypes, story forms, characters etc) ultimately impoverishes the creative culture as much as enclosure of software code hampers technological development. But that comes with reservations. I don’t want to see open-source creativity becoming a sweatshop for writers who can’t get published elsewhere than online, but can’t make a living from their work. Nor do I look forward with relish to a culture composed entirely of the top links on Fark, lolcats and tedious self-published doggerel, and devoid of big, powerful stories we can get our teeth into.

But though the way forwards may be a vision of the writer not as single creating consciousness but something more like a curator or editor, I haven’t yet seen anything successful emerge in this form, unless you count H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos – which was first created pre-internet. And while the open-source technology movement has evolved practices for navigating the tricky space around individual development and collective ownership, the Million Penguins debacle shows that there are far fewer practices for negotiating the relationship between individual and collective authorship of stories. They don’t teach collaborative imaginative writing in school.

Should they? The popularity of fanfic demonstrates that even if most of the fanfic fictional universes are created by one person before they are reappropriated, yet there is a demand for code that can be played with, added to, mutated and redeployed in this way. The fanfic universe is also beginning to develop interesting practices for peer-to-peer quality control. And the Web encourages this kind of activity. So how might we open-source the whole process? Is there anything that could be learned from OS coding about how to do stories in ways that acknowledge the networked, collaborative, open-sided and mutable nature of the Web?

Maybe memetic code is too different from the technical sort to let me stretch the metaphor that far. To put it another way: what social structures do writing collaborations need in order to produce great work in a way that’s both rigorous and open-sided? I think a mixture of lessons from bards, storytellers, improv theatre troupes, scriptwriting teams, open-source hacker practices, game development, Web2 business models and wiki etiquette may yet succeed in routing round the false dichotomy between proprietary quality and open-source memetic dross. And perhaps a practice developed in this way will figure out a way of enabling imaginative work (and its creators) to emerge through the Web without throwing the baby of cultural value out with the bathwater of proprietary content.

why is ‘world without oil’ such a bore?

I just had the following email exchange with Sebastian Mary about the World Without Oil alternate reality game (covered previously on if:book here and here). It seemed interesting enough to repost here.

BEN – Mon, May 14, 2007 at 4:59 PM EST

Hi there,

You found anything interesting yet going on at WWO?

I keep meaning to dig deeper, but nothing I’ve turned up is much good. Maudlin postcards from a pretty generic-feeling apocalypse is what most of it feels like to me. Perhaps I haven’t been looking in the right places, but my instinct at the moment is that the citizen journalist conceit was not the way to go. It’s “participatory” all right, but in that bland, superficial way that characterizes so many traditional media efforts at “interactivity.” Honestly, I’m surprised something like this got through the filter of folks as sophisticated as Jane McGonigal and co.

I think players need smaller pieces and hooks, elements of mystery to get their wheels turning — a story. As far as I can tell, this is the closest to intrigue there’s yet been, and it turned out to be nothing.

Would love to be shown something that suggests otherwise. Got anything?

Ben

SEB MARY – Mon, May 14, 2007 at 5:25 PM

Haven’t been following it closely to be honest. Up to the eyeballs with other work and don’t really have time to trawl acres of second-rate ‘What if…’. Plus, if I’m honest, despite my fetish for collaborative and distributed creativity I’m fussy about good prose, and amateur ‘creative writing’ doesn’t really grip me unless it’s so far from tradition (eg lolcats and the like) as to be good on its own terms. So though the idea intrigued me, I’ve not been hooked. I think it probably needs more story.

Which problem actually resonates with something else I’ve been pondering recently around collaborative writing. It bothers me that because people aren’t very good at setting up social structures within which more than one person can work on the same story (the total lack of anything of that sort in Million Penguins for example), you end up with this false dichotomy between quality products of one mind, and second-rate products of many, that ends up reinforcing the privileged position of the Author simply because people haven’t worked out an effective practice for any alternative. I think there’s something to be learned from the open-source coders about how you can be rigorous as well as collaborative.

sMary

BEN – Tue, May 15, 2007 at 12:50 AM

I don’t see why an ARG aimed at a social mobilization has to be so goddamn earnest. It feels right now like a middle school social studies assignment. But it could be subversive, dangerous and still highly instructive. Instead of asking players to make YouTube vids by candlelight, or Live Journal diaries reporting gloomily on around-the-block gas lines or the promise of local agriculture, why not orchestrate some real-world mischief, as is done in other ARGs.

This game should be generating memorable incursions of the hypothetical into the traffic of daily life, gnawing at the edges of people’s false security about energy. Create a car flash mob at a filling station and tie up several blocks of traffic in a cacophony of horns, maybe even make it onto the evening news. Or re-appropriate public green spaces for the planting of organic crops, like those California agrarian radicals with their “conspiracies of soil” in People’s Park back in the 60s. WWO’s worst offense, I think, is that it lacks a sense of humor. To sort of quote Oscar Wilde, the issues here are too important to take so seriously.

Ben

SEB MARY – Tue, May 15, 2007 at 5:34 AM

I totally agree that a sense of humour would make all the difference. There’s a flavour about it of top-down didactically-oriented pseudo-‘participation’, which in itself is enough to scupper something networked, even before you consider the fact that very few people like being lectured at in story form.

The trouble is, that humour around topics like this would index the PMs squarely to an activist agenda that includes people like the Reverend Billy, the Clown Army and their ilk. That’d be ace in my view; but it’s a risky strategy for anyone who’s reluctant to nail their political colours firmly to the anti-capitalist mast, which – I’d imagine – rules out most of Silicon Valley. It’s hard to see how you could address an issue like climate change in an infectious and mischievous way without rubbing a lot of people up the wrong way; I totally don’t blame McGonigal for having a go, but I think school-assignment-type pretend ‘citizen journalism’ is no substitute for playful subversiveness and – as you say – story hooks.

The other issue in play is as old as literary theory: the question of whether you dig ideas-based narrative or not. If the Hide & Seek Fest last weekend is anything to go by, the gaming/ARG community, young as it is, is already debating this. What place does ‘messaging’ have in games? Some see gaming as a good vehicle for inspiring, radical, even revolutionary messages, and some maintain that this misses the point.

Certainly, I think you have to be careful: games and stories have their own internal logic, and often don’t take kindly to being loaded with predetermined arguments. Even if I like the message, I think that it only works if it’s at the service of the experience (read story, game or both), and not the other way round. Otherwise it doesn’t matter how much interactivity you add, or how laudable your aim, it’s still boring.

sMary

a new face(book) for wikipedia?

It was pointed out to me the other day that Facebook has started its own free classified ad service, Facebook Marketplace (must be logged in), a sort of in-network Craigslist poised to capitalize on a built-in userbase of over 20 million. Commenting on this, Nicholas Carr had another thought:

But if Craigslist is a big draw for Facebook members, my guess is that Wikipedia is an even bigger draw. I’m too lazy to look for the stats, but Wikipedia must be at or near the top of the list of sites that Facebookers go to when they leave Facebook. To generalize: Facebook is the dorm; Wikipedia is the library; and Craigslist is the mall. One’s for socializing; one’s for studying; one’s for trading.

Which brings me to my suggestion for Zuckerberg [Facebook founder]: He should capitalize on Wikipedia’s open license and create an in-network edition of the encyclopedia. It would be a cinch: Suck in Wikipedia’s contents, incorporate a Wikipedia search engine into Facebook (Wikipedia’s own search engine stinks, so it should be easy to build a better one), serve up Wikipedia’s pages in a new, better-designed Facebook format, and, yes, incorporate some advertising. There may also be some social-networking tools that could be added for blending Wikipedia content with Facebook content.

Suddenly, all those Wikipedia page views become Facebook page views – and additional ad revenues. And, of course, all the content is free for the taking. I continue to be amazed that more sites aren’t using Wikipedia content in creative ways. Of all the sites that could capitalize on that opportunity, Facebook probably has the most to gain.

I’ve often thought this — not the Facebook idea specifically, but simply that five to ten years (or less) down the road, we’ll probably look back bemusedly on the days when we read Wikipedia on the actual Wikipedia site. We’ve grown accustomed to, even fond of it, but Wikipedia does still look and feel very much like a place of production, the goods displayed on the factory floor amid clattering machinery and welding sparks (not to mention periodic labor disputes). This blurring of the line between making and consuming is, of course, what makes Wikipedia such a fascinating project. But it does seem like it’s just a matter of time before the encyclopedia starts getting spun off into glossier, ad-supported packages. What other captive audience networks might be able to pull off their own brand of Wikipedia?

translating the past

At a certain point in college, I started doing all my word processing using Adobe FrameMaker. I won’t go into why I did this – I was indulging any number of idiosyncrasies then, many of them similarly unreasonable – but I did, and I kept using FrameMaker for most of my writing for a couple of years. Even in the happiest of times, there weren’t many people who used FrameMaker; in 2001, Adobe decided to cut their losses and stop supporting the Mac version of FrameMaker, which only ran in Classic mode anyway. I now have an Intel Mac that won’t run my old copy of FrameMaker; I now have a couple hundred pages of text in files with the extension “.fm” that I can’t read any more. Could I convert these to some modern format? Sure, given time and an old Mac. Is it worth it? Probably not: I’m pretty sure there’s nothing interesting in there. But I’m still loathe to delete the files. They’re a part, however minor, of a personal archive.

This is a familiar narrative when it comes to electronic media. The Institute has a room full of Voyager CD-ROMs which we have to fire up an old iBook to use, to say nothing of the complete collection of Criterion laser discs. I have a copy of Chris Marker’s CD-ROM Immemory which I can no longer play; a catalogue of a show on Futurism that an enterprising Italian museum put out on CD-ROM similarly no longer works. Unlike my FrameMaker documents, these were interesting products, which it would be nice to look at from time to time. Unfortunately, the relentless pace of technology has eliminated that choice.

Which brings me to the poet bpNichol, and what Jim Andrews’s site vispo.com has done for him. Born Barrie Phillip Nichol, bpNichol played an enormous part in the explosion of concrete and sound poetry in the 1960s. While he’s not particularly well known in the U.S., he was a fairly major figure in the Canadian poetry world, roughly analogous to the place of Ian Hamilton Finlay in Scotland. Nichol took poetry into a wide range of places it hadn’t been before; in 1983, he took it to the Apple IIe. Using the BASIC language, Nichol programmed poetry that took advantage of the dynamic new “page” offered by the computer screen. This wasn’t the first intersection of the computer and poetry – as far back as 1968, Dick Higgins wrote a FORTRAN program to randomize the lines in his Book of Love & War & Death – but it was certainly one of the first attempts to take advantage of this new form of text. Nichol distributed the text – a dozen poems – on a hundred 5.25” floppy disks, calling the collection First Screening.

Which brings me to the poet bpNichol, and what Jim Andrews’s site vispo.com has done for him. Born Barrie Phillip Nichol, bpNichol played an enormous part in the explosion of concrete and sound poetry in the 1960s. While he’s not particularly well known in the U.S., he was a fairly major figure in the Canadian poetry world, roughly analogous to the place of Ian Hamilton Finlay in Scotland. Nichol took poetry into a wide range of places it hadn’t been before; in 1983, he took it to the Apple IIe. Using the BASIC language, Nichol programmed poetry that took advantage of the dynamic new “page” offered by the computer screen. This wasn’t the first intersection of the computer and poetry – as far back as 1968, Dick Higgins wrote a FORTRAN program to randomize the lines in his Book of Love & War & Death – but it was certainly one of the first attempts to take advantage of this new form of text. Nichol distributed the text – a dozen poems – on a hundred 5.25” floppy disks, calling the collection First Screening.

bpNichol died in 1988, about the time the Apple IIe became obsolete; four years later, a HyperCard version of the program was constructed. HyperCard’s more or less obsolete now. In 2004, Jim Andrews, Geof Huth, Lionel Kerns, Marko Niemi, and Dan Waber began a three-year process of making First Screening available to modern readers; their results are up at http://vispo.com/bp/. They’ve made Nichol’s program available in four forms: image files of the original disk that can be run with an Apple II emulator, with the original source should you want to type in the program yourself; the HyperCard version that was made in 1992; a QuickTime movie of the emulated version playing; and a JavaScript implementation of the original program. They also provide abundant and well thought out criticism and context for what Nichol did.

Looking at the poems in any version, there’s a sweetness to the work that’s immediately winning, whatever you think of concrete poetry or digital literature. Apple BASIC seems cartoonishly primitive from our distance, but Nichol took his medium and did as much as he could with it. Vispo.com’s preservation effort is to be applauded as exemplary digital archiving.

But some questions do arise: does a work like this, defined so precisely around a particular time and environment, make sense now? Certainly it’s important historically, but can we really imagine that we’re seeing the work as Nichol intended it to be seen? In his printed introduction included with the original disks, Nichol speaks to this problem:

As ever, new technology opens up new formal problems, and the problems of babel raise themselves all over again in the field of computer languages and operating systems. Thus the fact that this disk is only available in an Applesoft Basic version (the only language I know at the moment) precisely because translation is involved in moving it out further. But that inherent problem doesn’t take away from the fact that computers & computer languages also open up new ways of expressing old contents, of revivifying them. One is in a position to make it new.

Nichol’s invocation of translation seems apropos: vispo.com’s versions of First Screening might best be thought of as translations from a language no longer spoken. Translation of poetry is the art of failing gracefully: there are a lot of different ways to do it, and in each way something different is lost. The QuickTime version accurately shows the poems as they appeared on the original computer, but video introduces flickering discrepancies because of the frame rate. With the Javascript version, our eyes aren’t drawn to the craggy bitmapped letters (in a way that eyes looking at an Apple monitor in 1983 would not have been), but there’s no way to interact with the code in the way Nichol suggests because the code is different.

Nichol’s invocation of translation seems apropos: vispo.com’s versions of First Screening might best be thought of as translations from a language no longer spoken. Translation of poetry is the art of failing gracefully: there are a lot of different ways to do it, and in each way something different is lost. The QuickTime version accurately shows the poems as they appeared on the original computer, but video introduces flickering discrepancies because of the frame rate. With the Javascript version, our eyes aren’t drawn to the craggy bitmapped letters (in a way that eyes looking at an Apple monitor in 1983 would not have been), but there’s no way to interact with the code in the way Nichol suggests because the code is different.

Vispo.com’s work is quite obviously a labor of love. But it does raise a lot of questions: if Nichol’s work wasn’t so well-loved, would anyone have bothered preserving it like this? Part of the reason that Nichol’s work can be revived is that he left his code open. Given the media he was working in, he didn’t have that much of a choice; indeed, he makes it part of the work. If he hadn’t – and this is certainly the case with a great deal of work contemporary to his – the possibilities of translation would have been severely limited. And a bigger question: if vispo.com’s work is to herald a new era of resurrecting past electronic work, as bpNichol might have imagined that his work was to herald a new era of electronic poetry, where will the translators come from?

the problem of criticism

An email fluttered into my inbox yesterday afternoon, advertising a reading that night by the novelist Richard Powers, a “talk-piece about literature, empathy, and collective forgetting in the age of blogs.” Powers is on a short list of American novelists who write convincingly about how technology affects our humanity – see, for example: Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance, on the mechanical reproduction of art; Galatea 2.2, on artificial intelligence; Ploughing the Dark, on virtual reality and collective imagination – and I’ve been wondering about the problem of forgetting, so I wandered over to the Morgan Library, curious to hear what he had to say.

An email fluttered into my inbox yesterday afternoon, advertising a reading that night by the novelist Richard Powers, a “talk-piece about literature, empathy, and collective forgetting in the age of blogs.” Powers is on a short list of American novelists who write convincingly about how technology affects our humanity – see, for example: Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance, on the mechanical reproduction of art; Galatea 2.2, on artificial intelligence; Ploughing the Dark, on virtual reality and collective imagination – and I’ve been wondering about the problem of forgetting, so I wandered over to the Morgan Library, curious to hear what he had to say.

There’s always room for trepidation about the old guard confronting the new – one remembers the embarrassingly malformed web address that figures in at least the first edition of Don DeLillo’s Underworld – but Powers didn’t disappoint: his piece, entitled “The Moving Finger,” nicely conveys how blog-reading works, and in particular the voyeur-like experience of being caught up with an individual voice. Speaking in the first person, Powers recounted the story of a novelist obsessed with a blog entitled Speculum Ludi, helmed by someone who calls himself Funes the Memoirist, whose ranting posts on the deeper meaning of mirror neurons and advances in cognitive neurobiology were quite ably read by the critic John Leonard. Powers finds Funes’s blog by accident, then follows a common blog-reading trajectory: he doubts its credibility, finds himself compelled by the turns of phrase, sleuths down who must be behind it, lingers over his RSS reader, waiting for updates. And then he’s caught: Funes eventually realizes that he has only a single reader and calls him out by IP address. Powers panics; Funes retaliates by shutting down his blog & erasing all traces of it from the Internet. (This last bit might be where Powers goes too far.)

There’s a weird sense of intimacy that comes from reading blogs. When we read a novel, we know exactly where we stand with respect to the author; what’s in the book is packaged and done. A blog goes on. While I’m sure Powers’s piece will end up in print sooner or later, it makes sense as an oral presentation, leapfrogging the solidity of written language into the memory of his listeners. (And from there to the inevitable blog reports: see Ed Park’s and Galleycat’s). There’s an echo of this in Powers’s widely discussed writing method: he composes via tablet PC and dictation software, bypassing the abstraction of the keyboard altogether.

But that said, it would be a mistake to read Powers as championing the new at the expense of the old. There’s been a great deal of worry of late about litblogs killing off newspaper book reviews; naturally this came up in the discussion afterwards. Powers pointed out that while there’s an enormous amount of potential in the pluralist free-for-all that is the blogosphere, online criticism isn’t free of the same market forces that increasingly dictate the content of newspaper book reviews. Amazon.com maintains what’s probably the biggest collection of book reviews in the world; Powers wondered how many of those reviews would be written if the reviewers weren’t allowed to declare how many stars a book merited. There’s something tempting about giving an under-appreciated book five stars; there’s equally tempting about bringing down the rating of something that’s overrated. But this sort of quick evaluation, he argued, isn’t the same thing as criticism; while all books may be judged with the same scale in the eyes of the market, rating a book isn’t necessarily engaging with it in a substantive way. The reciprocity in web reading writing is fantastic, but it comes with demands: among them the need for equitable discourse. Criticism is communication, not grading. Powers’s narrator fails because he refuses to be critic as well as reader. We may all be critics now, but there’s a responsibility that comes from that.

But that said, it would be a mistake to read Powers as championing the new at the expense of the old. There’s been a great deal of worry of late about litblogs killing off newspaper book reviews; naturally this came up in the discussion afterwards. Powers pointed out that while there’s an enormous amount of potential in the pluralist free-for-all that is the blogosphere, online criticism isn’t free of the same market forces that increasingly dictate the content of newspaper book reviews. Amazon.com maintains what’s probably the biggest collection of book reviews in the world; Powers wondered how many of those reviews would be written if the reviewers weren’t allowed to declare how many stars a book merited. There’s something tempting about giving an under-appreciated book five stars; there’s equally tempting about bringing down the rating of something that’s overrated. But this sort of quick evaluation, he argued, isn’t the same thing as criticism; while all books may be judged with the same scale in the eyes of the market, rating a book isn’t necessarily engaging with it in a substantive way. The reciprocity in web reading writing is fantastic, but it comes with demands: among them the need for equitable discourse. Criticism is communication, not grading. Powers’s narrator fails because he refuses to be critic as well as reader. We may all be critics now, but there’s a responsibility that comes from that.

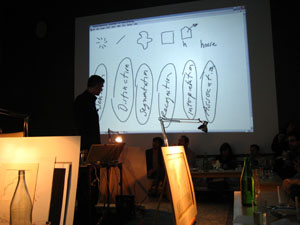

chromograms: visualizing an individual’s editing history in wikipedia

The field of information visualization is cluttered with works that claim to illuminate but in fact obscure. These are what Brad Paley calls “write-only” visualizations. If you put information in but don’t get any out, says Paley, the visualization has failed, no matter how much it dazzles. Brad discusses these matters with the zeal of a spiritual seeker. Just this Monday, he gave a master class in visualization on two laptops, four easels, and four wall screens at the Institute’s second “Monkeybook” evening at our favorite video venue in Brooklyn, Monkeytown. It was a scintillating performance that left the audience in a collective state of synaptic arrest.

Jesse took some photos:

We stand at a crucial juncture, Brad says, where we must marshal knowledge from the relevant disciplines — design, the arts, cognitive science, engineering — in order to build tools and interfaces that will help us make sense of the huge masses of information that have been dumped upon us with the advent of computer networks. All the shallow efforts passing as meaning, each pretty piece of infoporn that obfuscates as it titillates, is a drag on this purpose, and a muddying of the principles of “cognitive engineering” that must be honed and mastered if we are to keep a grip on the world.

With this eloquent gospel still echoing in my brain, I turned my gaze the next day to a new project out of IBM’s Visual Communication Lab that analyzes individuals’ editing histories in Wikipedia. This was produced by the same team of researchers (including the brilliant Fernanda Viegas) that built the well known History Flow, an elegant technique for visualizing the revision histories of Wikipedia articles — a program which, I think it’s fair to say, would rate favorably on the Paley scale of readability and illumination. Their latest effort, called “Chromograms,” hones in the activities of individual Wikipedia editors.

The IBM team is interested generally in understanding the dynamics of peer to peer labor on the internet. They’ve focused on Wikipedia in particular because it provides such rich and transparent records of its production — each individual edit logged, many of them discussed and contextualized through contributors’ commentary. This is a juicy heap of data that, if placed under the right set of lenses, might help make sense of the massively peer-produced palimpsest that is the world’s largest encyclopedia, and, in turn, reveal something about other related endeavors.

Their question was simple: how do the most dedicated Wikipedia contributors divvy up their labor? In other words, when someone says, “I edit Wikipedia,” what precisely do they mean? Are they writing actual copy? Fact checking? Fixing typos and syntactical errors? Categorizing? Adding images? Adding internal links? External ones? Bringing pages into line with Wikipedia style and citation standards? Reverting vandalism?

All of the above, of course. But how it breaks down across contributors, and how those contributors organize and pace their work, is still largely a mystery. Chromograms shed a bit of light.

For their study, the IBM team took the edit histories of Wikipedia administrators: users to whom the community has granted access to the technical backend and who have special privileges to protect and delete pages, and to block unruly users. Admins are among the most active contributors to Wikipedia, some averaging as many as 100 edits per day, and are responsible more than any other single group for the site’s day-to-day maintenance and governance.

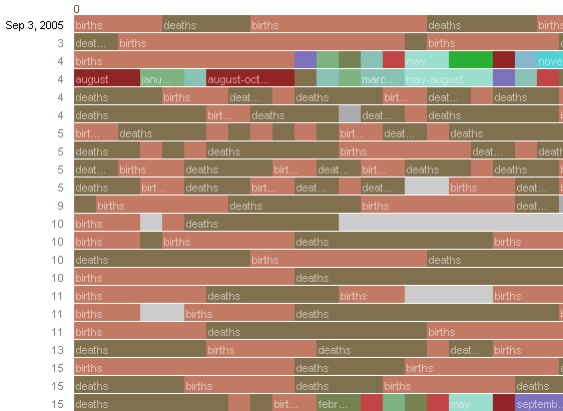

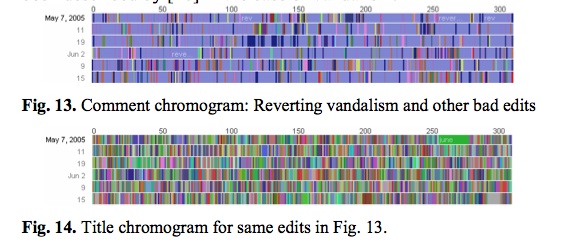

What the researches essentially did was run through the edit histories with a fine-toothed, color-coded comb. A chromogram consists of multiple rows of colored tiles, each tile representing a single edit. The color of the tile corresponds with the first letter of the text in the edit, or in the case of “comment chromograms,” the first letter of the user’s description of their edit. Colors run through the alphabet, starting with numbers 1-10 in hues of gray and then running through the ROYGBIV spectrum, A (red) to violet (Z).

It’s a simple system, and one that seems arbitrary at first, but it accomplishes the important task of visually separating editorial actions, and making evident certain patterns in editors’ workflow.

Much was gleaned about the way admins divide their time. Acvitity often occurs in bursts, they found, either in response to specific events such as vandalism, or in steady, methodical tackling of nitpicky, often repetitive, tasks — catching typos, fixing wiki syntax, labeling images etc. Here’s a detail of a chromogram depicting an administrator’s repeated entry of birth and death information on a year page:

The team found that this sort of systematic labor was often guided by lists, either to-do lists in Wikiprojects, or lists of information in articles (a list of naval ships, say). Other times, an editing spree simply works progressively through the alphabet. The way to tell? Look for rainbows. Since the color spectrum runs A to Z, rainbow patterned chromograms depict these sorts of alphabetically ordered tasks. As in here:

This next pair of images is almost moving. The top one shows one administrator’s crusade against a bout of vandalism. Appropriately, he’s got the blues, blue corresponding with “r” for “revert.” The bottom image shows the same edit history but by article title. The result? A rainbow. Vandalism from A to Z.

Chromograms is just one tool that sheds light on a particular sort of editing activity in Wikipedia — the fussy, tedious labors of love that keep the vast engine running smoothly. Visualizing these histories goes some distance toward explaining how the distributed method of Wikipedia editing turns out to be so efficient (for a far more detailed account of what the IBM team learned, it’s worth reading this pdf). The chromogram technique is probably too crude to reveal much about the sorts of editing that more directly impact the substance of Wikipedia articles, but it might be a good stepping stone.

Learning how to read all the layers of Wikipedia is necessarily a mammoth undertaking that will require many tools, visualizations being just one of them. High-quality, detailed ethnographies are another thing that could greatly increase our understanding. Does anyone know of anything good in this area?

nibbling at the corners of open-access

Here at the Institute, we take as one of our fundamental ideas that intellectual output should be open for reading and remixing. We try to put that idea into practice with most of our projects. With MediaCommons we have set that as a cornerstone with the larger aim of transforming the culture of the academy to entice professors and students to play in an open space. Some of the benefits that can be realized by being open: a higher research profile for an institution, better research opportunities, and, as a peripheral (but ultimate) benefit: a more active intellectual culture. Open-access is hardly a new idea—the Public Library of Science has been building a significant library of articles for over seven years—but the academy is still not totally convinced.

A news clip in the Communications of the ACM describes a new study by Rolf Wigand and Thomas Hess from U. of Arkansas, and Florian Mann and Benedikt von Walter from Munich’s Institute for IS and New Media that looked at attitudes towards open access publishing.

academics are extremely positive about new media opportunities that provide open access to scientific findings once available only in costly journals but fear nontraditional publication will hurt their chances of promotion and tenure.

Distressingly, not enough academics yet have faith in open access publishing as a way to advance their careers. This is an entrenched problem in the institutions and culture of academia, and one that hobbles intellectual discourse in the academy and between our universities and the outside world.

Although 80% said they had made use of open-access literature, only 24% published their work online. In fact, 65% of IS researchers surveyed accessed online literature, but only 31% published their own research on line. In medical sciences, those numbers were 62% and 23% respectively.

The majority of academics (based on this study) aren’t participating fully in the open access movement—just nibbling at the corners. We need to encourage greater levels of participation, and greater levels of acceptance by institutions so that we can even out the disparity between use and contribution.

the alternate universe algorithm

“What if you could travel to parallel worlds: the same year, the same earth, only different dimensions…?”

That’s the opening line to one of my favorite science fiction shows in the 90s called “Sliders.” The premise of the show was simple: a group of lost travelers traverse through different dimensions where history has played itself out differently, and need to navigate through unfamiliar cultural norms, values and beliefs. What if the United States lost the American Revolutionary War? Penicillin was never discovered? or gender roles reversed?

An aspect of the show that I found interesting was in how our protagonists quickly adapted to subtly different worlds and developed a method for exploration: after their initial reconnaissance, they’d reconvene in a hotel room (when it existed) and assess their – often dire – situation.

The way they “browsed” these alternate worlds stuck with me when reading Mary’s recent posts on new forms of fiction on the web:

Web reading tends towards entropy. You go looking for statistics on the Bornean rainforest and find yourself reading the blog of someone who collects orang utan coffee mugs. Anyone doing sustained research on the Web needs a well-developed ability to navigate countless digressions, and derive coherence from the sea of chatter.

Browsing takes us to unexpected places, but what about the starting point? Browsing does not begin arbitrarily. It usually begins in a trusted location, like a homepage or series of pages that you can easily refer back to or branch out from. But ARGs (Alternate Reality Games), like World Without Oil, which Ben wrote about recently, require you to go some obscure corner of the internet and engage with it as if it was trusted source. What if the alternate world existed everywhere you went, like in Sliders?

In college, a friend of mine mirrored whitehouse.gov and replaced key words and phrases with terms he thought were more fitting. For example, “congressmen” was replaced by “oil-men” and “dollars” with “petro-dollars.” He had a clear idea of the world he wanted people to interact with (knowingly or not). The changes were subtle and website looked legitimate it and ultimately garnered lots of attention. Those who understood what was going on sent their praise and those who did not, sent confused and sometimes angry emails about their experience. A

(I believe he eventually he blocked the domain because he found it disconcerting that most traffic came from the military)

Although we’ll need very sophisticated technology to apply more interesting filters across large portions of the internet, I think “Fiction Portals”, engines that could alter the web slightly according to the “author” needs, could change the role of an author in an interesting way.

I want to play with the this idea of an author: Like a scientist, the author would need to understand how minor changes to society would manifest themselves across real content, tweaking words and ideas ever so slightly to produce a world that is that is vast, believable, and could be engaged from any direction, hopefully revealing some interesting truths about the real world.

So, after playing around with this idea for a bit, I threw together a very primitive prototype that alters the internet in a subtle way (maybe too subtle?) but I think hints at a form that could eventually allow us to Slide.

the persistence of memory

Jorge Luis Borges tells the story of “Funes, the Memorious,” a man from Uruguay who, after an accident, finds himself blessed with perfect memory. Ireneo Funes remembers everything that he encounters; he can forget nothing that he’s seen or heard, no matter how minor. As one might expect, this blessing turns out to be a curse: overwhelmed by his impressions of the world, Funes can’t leave his darkened room. Worse, he can’t make sense of the vast volume of his impressions by classifying them. Funes’s world is made up entirely of hapax legomena. He has no general concepts:

Jorge Luis Borges tells the story of “Funes, the Memorious,” a man from Uruguay who, after an accident, finds himself blessed with perfect memory. Ireneo Funes remembers everything that he encounters; he can forget nothing that he’s seen or heard, no matter how minor. As one might expect, this blessing turns out to be a curse: overwhelmed by his impressions of the world, Funes can’t leave his darkened room. Worse, he can’t make sense of the vast volume of his impressions by classifying them. Funes’s world is made up entirely of hapax legomena. He has no general concepts:

“Not only was it difficult for him to see that the generic symbol ‘dog’ took in all the dissimilar individuals of all shapes and sizes, it irritated him that the ‘dog’ of three-fourteen in the afternoon, seen in profile, should be indicated by the same noun as the dog of three-fifteen, seen frontally. His own face in the mirror, his own hands, surprised him every time he saw them.”

(p. 136 in Andrew Hurley’s translation of Collected Fictions.) Funes dies prematurely, alone and unrecognized by the world; while we are told that he died of “pulmonary congestion,” it’s clear that Funes has drowned in his memories. While there are advantages to remembering everything, Borges’s narrator realizes his superiority to Funes:

(p. 136 in Andrew Hurley’s translation of Collected Fictions.) Funes dies prematurely, alone and unrecognized by the world; while we are told that he died of “pulmonary congestion,” it’s clear that Funes has drowned in his memories. While there are advantages to remembering everything, Borges’s narrator realizes his superiority to Funes:

“He had effortlessly learned English, French, Portuguese, Latin. I suspect, nevertheless, that he was not very good at thinking. To think is to ignore (or forget) differences, to generalize, to abstract. In the teeming world of Ireneo Funes there was nothing but particulars – and they were virtually immediate particulars.”

(p. 137) Borges’s story isn’t really about memory as much as it is about how we make sense of the world. It’s important to forget things, to ignore the minor differences between similar objects. We recognize that the dog the Funes sees at three-fourteen and the dog that he sees at three-fifteen are the same; Funes does not. Funes dies insane; we, hopefully, do not.

(p. 137) Borges’s story isn’t really about memory as much as it is about how we make sense of the world. It’s important to forget things, to ignore the minor differences between similar objects. We recognize that the dog the Funes sees at three-fourteen and the dog that he sees at three-fifteen are the same; Funes does not. Funes dies insane; we, hopefully, do not.

I won’t pretend to be the first to see in the Internet parallels to the all-remembering mind of Funes; a book could be written, if it hasn’t already been, on how Borges invented the Internet. It’s interesting, however, to see that the problems of Funes are increasingly everyone’s problems. As humans, we forget by default; maybe it’s the greatest sign of the Internet’s inhumanity that it remembers. With time things become more obscure on the Internet; you might need to plumb the Wayback Machine at archive.org rather than Google to find a website from 1997. History becomes obscure, but it only very rarely disappears entirely on the Internet.

I won’t pretend to be the first to see in the Internet parallels to the all-remembering mind of Funes; a book could be written, if it hasn’t already been, on how Borges invented the Internet. It’s interesting, however, to see that the problems of Funes are increasingly everyone’s problems. As humans, we forget by default; maybe it’s the greatest sign of the Internet’s inhumanity that it remembers. With time things become more obscure on the Internet; you might need to plumb the Wayback Machine at archive.org rather than Google to find a website from 1997. History becomes obscure, but it only very rarely disappears entirely on the Internet.

A recent working paper by Viktor Mayer-Schoenberger, a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, recognizes the problems of the Internet’s elephantine memory. He suggests pre-emptively dealing with the issues that are sure to spring up in the future by actively building forgetting into the systems that comprise the network. Mayer-Schoenberger envisions that some of this forgetting would be legally enforced: commercial sites might be required to state how long they will keep customer’s information, for example.

A recent working paper by Viktor Mayer-Schoenberger, a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, recognizes the problems of the Internet’s elephantine memory. He suggests pre-emptively dealing with the issues that are sure to spring up in the future by actively building forgetting into the systems that comprise the network. Mayer-Schoenberger envisions that some of this forgetting would be legally enforced: commercial sites might be required to state how long they will keep customer’s information, for example.

It’s an interesting proposal, if firmly in the realm of the theoretical: it’s hard to imagine that the public will be proactive enough about this issue to push the government to take issue any time soon. Give it time, though: in a decade, there will be a generation dealing with embarrassing ten-year-old MySpace photos. Maybe we’ll no longer be embarrassed about our pasts; maybe we won’t trust anything on the Internet at that point; maybe we’ll demand mandatory forgetting so that we don’t all go crazy.

It’s an interesting proposal, if firmly in the realm of the theoretical: it’s hard to imagine that the public will be proactive enough about this issue to push the government to take issue any time soon. Give it time, though: in a decade, there will be a generation dealing with embarrassing ten-year-old MySpace photos. Maybe we’ll no longer be embarrassed about our pasts; maybe we won’t trust anything on the Internet at that point; maybe we’ll demand mandatory forgetting so that we don’t all go crazy.

Images from Hollis Frampton’s film (nostalgia), 1971.