…is officially live! Check it out. Spread the word.

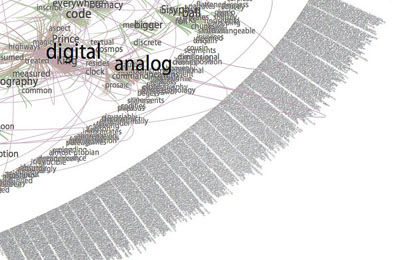

I want to draw special attention to the Gamer Theory TextArc in the visualization gallery – a graphical rendering of the book that reveals (quite beautifully) some of the text’s underlying structures.

Gamer Arc detail

TextArc was created by Brad Paley, a brilliant interaction designer based in New York. A few weeks ago, he and Ken Wark came over to the Institute to play around with the Gamer Theory in TextArc on a wall display:

Ken jotted down some of his thoughts on the experience: “Brad put it up on the screen and it was like seeing a diagram of my own writing brain…” Read more here (then scroll down partway).

starting bottom-left, counter-clockwise: Ken, Brad, Eddie, Bob

More thoughts about all of this to come. I’ve spent the past two days running around like a madman at the Digital Library Federation Spring Forum in Pasadena, presenting our work (MediaCommons in particular), ducking in and out of sessions, chatting with interesting folks, and pounding away at the Gamer site — inserting footnote links, writing copy, generally polishing. I’m looking forward to regrouping in New York and processing all of this.

Thanks, Florian Brody for the photos.

Oh, and here is the “official” press/blogosphere release. Circulate freely:

The Institute for the Future of the Book is pleased to announce a new edition of the “networked book” Gamer Theory by McKenzie Wark. Last year, the Institute published a draft of Wark’s path-breaking critical study of video games in an experimental web format designed to bring readers into conversation around a work in progress. In the months that followed, hundreds of comments poured in from gamers, students, scholars, artists and the generally curious, at times turning into a full-blown conversation in the manuscript’s margins. Based on the many thoughtful contributions he received, Wark revised the book and has now published a print edition through Harvard University Press, which contains an edited selection of comments from the original website. In conjunction with the Harvard release, the Institute for the Future of the Book has launched a new Creative Commons-licensed, social web edition of Gamer Theory, along with a gallery of data visualizations of the text submitted by leading interaction designers, artists and hackers. This constellation of formats — read, read/write, visualize — offers the reader multiple ways of discovering and building upon Gamer Theory. A multi-mediated approach to the book in the digital age.

http://web.futureofthebook.org/mckenziewark/

More about the book:

Ever get the feeling that life’s a game with changing rules and no clear sides, one you are compelled to play yet cannot win? Welcome to gamespace. Gamespace is where and how we live today. It is everywhere and nowhere: the main chance, the best shot, the big leagues, the only game in town. In a world thus configured, McKenzie Wark contends, digital computer games are the emergent cultural form of the times. Where others argue obsessively over violence in games, Wark approaches them as a utopian version of the world in which we actually live. Playing against the machine on a game console, we enjoy the only truly level playing field–where we get ahead on our strengths or not at all.

Gamer Theory uncovers the significance of games in the gap between the near-perfection of actual games and the highly imperfect gamespace of everyday life in the rat race of free-market society. The book depicts a world becoming an inescapable series of less and less perfect games. This world gives rise to a new persona. In place of the subject or citizen stands the gamer. As all previous such personae had their breviaries and manuals, Gamer Theory seeks to offer guidance for thinking within this new character. Neither a strategy guide nor a cheat sheet for improving one’s score or skills, the book is instead a primer in thinking about a world made over as a gamespace, recast as an imperfect copy of the game.

——————-

The Institute for the Future of the Book is a small New York-based think tank dedicated to inventing new forms of discourse for the network age. Other recent publishing experiments include an annotated online edition of the Iraq Study Group Report (with Lapham’s Quarterly), Without Gods: Toward a History of Disbelief (with Mitchell Stephens, NYU), and MediaCommons, a digital scholarly network in media studies. Read the Institute’s blog, if:book. Inquiries: curator [at] futureofthebook [dot] org

McKenzie Wark teaches media and cultural studies at the New School for Social Research and Eugene Lang College in New York City. He is the author of several books, most recently A Hacker Manifesto (Harvard University Press) and Dispositions (Salt Publishing).

if:book

A Project of the Institute for the Future of the Book

That’s one of the most beautiful things I’ve seen in a long time. Nice one guys.

Magnificent achievement.

My first association was with Ong’s study of Ramus and the ramifications of depicting ideas in space. “The invention of printing from movable type cast from a mold or matrix made with a punch….had to wait on a profound reorientation within the human spirit which made it possible to think of all the possessions of the mind, that is, of knowledge and of expression, in terms more committed to space than those of earlier times.” (p.308)

My second association was with a mirror of the mind for spatial arrangement of ideas. The mirror does not reverse left to right but from front to back. As an example of this distinction look at a clock in a mirror and see how difficult it is to tell the time until you imagine your self looking through a transparent dial from the back of the clock. Earliest photography (Daguerriotype) also was mirror “reversed” much to the disconcertion of the subjects.

In these classical contexts of the mirror the light reflected is supplied by the sun. In the mirror of the computer screen the light presented is produced by electrical charge engendered by code. (Gary, where are you going with this?) Take Second Life for example. Here there is no sunlight to mirror the world. Every depiction must be encoded. But the image in the mirror begins to be seen except the “observer” is shifted behind the sun world.

This computer presented mirror is different from sun rendered print. Another metaphor for the screen is the night sky, dots on black that require special encoded interpretation. But Ong’s Ramus “method” of deploying ideas in space is at work in both. Neither spacial depiction of ideas, print or screen, is self referencial (except by a presumptive observer). Both actually are two different methods of visualizing ideas that reference each other.

Following Ben’s links, those stepping stones to better apprehend this project, I read something that McKenzie Wark wrote last May, where he says that game culture is more intellectual than film culture or literary culture, but that since games have their unique characteristics, comparisons are somehow illegitimate. That brought to mind three recent instances: the first one, Zlajov Zizek opening words in Sophie Fiennes documentary “The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema:” “Cinema is the ultimate pervert art, it doesn’t give you what you desire, it tells you how to desire.” After psychoanalytical interpretation of scenes and locations of dozens of movies, he concludes that games are the locus where one can realize the most intimate desires, where gamers project who they truly are. The second one, Eva and Franco Mattes’s “13 Most Beautiful Avatars,” a series of portraits of avatars. For them, Second Life is a place where “you are forced not to be yourself, to wear an ultra-modern 3D mask. But masks are not there to hide your real identity, on the contrary they are there to show who you really are, since you can ignore social restrictions. Since we’ve been living fake identities all of our lives, it’s obvious that we are attracted by a world of Avatars.” The third one, Paolo Cherchi Usai’s “Passio,” a series of silent film clips documenting experiments with human subjects, set to Arvo Pärt’s St. John Passion (“Passio”.) These disturbing images were projected at the cathedral of Saint John the Divine, while the Trinity Choir sang Pärt’s beautiful score to St. John’s sorrowful text. The cavernous structure of the cathedral was the perfect place. As I walked out, I realized why I have never been able to talk myself into seeing a movie on a laptop. When the lights are on, the world is distracting in its banality. In the cave one might see projected images of stark reality. Cellphone off, in the dark, a passive viewer, not an active gamer, if the movie is any good, one walks out without answers. No heroic deeds achieved.

Gamer Theory 3.0: The Visualizations beautifully cracks open the surface of the text and manifests our nature as people of the word. As McKenzie Wark expresses it, “for every sentence on the page (or screen) there are thousands of other sentences that could be in its place.” The relationships between words within a text in a spatial form result in clusters that surprise even the enouncing subject, who discovers, literally aprè s la lettre, that this is not only words, but concepts overlap. Referring to how this happens in Gamer Theory 3.0, Wark says, “there’s something uncanny about the ‘theory’ ‘entertainment’ overlap. I have thought about writing something about this, and maybe the thought is already in the text before I have gotten around to writing it.” Thus, he presents TextArc as a way of reading as well as a way of writing. He is thinking as a reader of his writing from the viewpoint of where his words fall within the spatial coordinates of the text as the text writes itself by reading itself. McKenzie Wark has written the theory of games in a participatory way, like a game, but what has remained is contextual, it belongs to the thinking process. That is how he is “reading” Text Arc.