Pedro Meyer, founder of ZoneZero, the pioneering photography site, just wrote to say that he’s working on an Ipod version of I Photograph to Remember, the cdrom he made in the early 90s. It’s a deeply moving portrait documenting the last years of his parents’ life. Pedro invites readers of if:book to download a beta version HERE. He’s hoping for feedback so please send comments.

I thought it might be interesting to describe the debut of IPTR at the Digital World Conference in Beverly Hills in 1991. To appreciate this you have to understand that at that time no one had ever really seen anything on a computer screen with emotional content. The audience consisted of hyperactive, mostly male, senior executives who normally couldn’t sit still or be quiet for five minutes. But for thirty-two minutes, from the moment the lights went down till the closing credits, there wasn’t even the sound of breathing. People were literally stunned as they suddenly realized that the number-crunching, text processing machine on their desk could convey complex, profound feelings.

Monthly Archives: September 2006

what’s important to save

Rick Prelinger and Megan Shaw visited for lunch earlier in the week and gave us a preview of the very interesting presentation they made later that day about the SF-based Prelinger Library . Beginning in the 70s Rick started collecting film and video that no one else seemed to want — industrials (e.g. GM’s worldfair and auto show films), educational films (think “how to be popular”, “how to be a good citizen” and how to make the perfect jelly), and filmed advertisements to be shown in movie theaters and early TV. Rick’s contention, as the first serious media archaeologist, was that these films that no one intended to be saved or seen again — ephemeral films — often provided much more insight about howsociety has evolved in the twentieth century than the big budget hollywood films which tend to be more self-conscious and indirect.

Below are a few clips from some of my favorites. the clip from “A Date With Your Family” contains one of the scariest moments i’ve ever encountered in film, when at the end of the clip, the narrator remarks as “father” returns from his day at the office . . . . that “these boys greet their dad AS THOUGH they are genuinely glad to see him, AS THOUGH they had really missed being away from him during the day . . . ” In the second clip, “A Young Man’s Fancy,” the daughter in a pensive mood says “I was just thinking” and the mother says incredulously, “thinking?” as if that’s the most outlandish thing she can imagine her daughter doing.

A few years ago, the Library of Congress, recognizing the inestimable value of Rick’s collection, bought the whole kit and caboodle. Since then, Rick and his partner, Megan Shaw have turned their attention to print, building a library of unusual books, periodicals and print ephemera; e.g. an invaluable collection of ESSO’s state maps from the fities that favors serendipitous browsing and remix. (the cover of the ESSO map below depicts a young boy being introduced by his dad to the wonders of nuclear fusion).

The following is from the description on the library’s website:

Though libraries live on (and are among the least-corrupted democratic institutions), the freedom to browse serendipitously is becoming rarer. Now that many research libraries are economizing on space and converting print collections to microfilm and digital formats, it’s becoming harder to wander and let the shelves themselves suggest new directions and ideas. Key academic and research libraries are often closed to unaffiliated users, and many keep the bulk of their collections in closed stacks, inhibiting the rewarding pleasures of browsing. Despite its virtues, query-based online cataloging often prevents unanticipated yet productive results from turning up on the user’s screen. And finally, much of the material in our collection is difficult to find in most libraries readily accessible to the general public.

While listening to Rick and Megan’s talk i had a minor AHA moment. a lot of our skepticism and concern about Google centers on the inherent dangers of a private company being entrusted with the care and feeding of our increasingly digitize culture. When Rick and Megan showed the cover of School Executives, a journal from the 40s, which featured an article on the value of teachers toting guns to enforce classroom discipline, i realized that Google’s digitization efforts focus entirely on codex books (maybe to be extended to periodicals that libraries have bothered to store). but the invaluable materials that might be called “print-based” ephemera — pamphlets, marketing materials, off-beat journals, zines etc. — will be absent in the future. The sad thing about this, as we know from Rick’s ephemeral film collection, is that often these pieces that were never meant to survive tell us more about how our culture evolved and how we’ve ended up where we are, than many self-conscious efforts conceived with permanence in mind.

amazon looks to “kindle” appetite for ebooks with new device

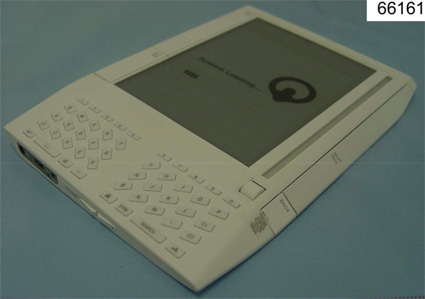

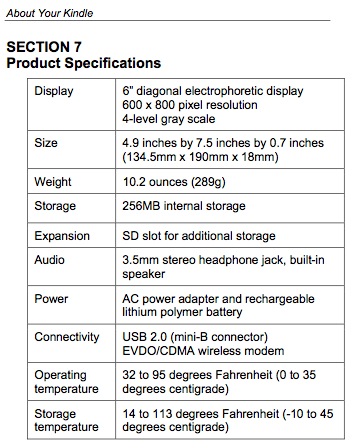

Engadget has uncovered details about a soon-to-be-released upcoming/old/bogus(?) Amazon ebook reading device called the “Kindle,” which appears to have an e-ink display, and will presumably compete with the Sony Reader. From the basic specs they’ve posted, it looks like Kindle wins: it’s got more memory, it’s got a keyboard, and it can connect to the network (update: though only through the EV-DO wireless standard, which connects Blackberries and some cellphones; in other words, no basic wifi). This is all assuming that the thing actually exists, which we can’t verify.

Regardless, it seems the history of specialized ebook devices is doomed to repeat itself. Better displays (and e-ink is still a few years away from being really good) and more sophisticated content delivery won’t, in my opinion, make these machines much more successful than their discontinued forebears like the Gemstar or the eBookMan.

Ebooks, at least the kind Sony and Amazon will be selling, dwell in a no man’s land of misbegotten media forms: pale simulations of print that harness few of the possibilities of the digital (apparently, the Sony Reader won’t even have searchable text!). Add highly restrictive DRM and vendor lock-in through the proprietary formats and vendor sites made for these devices and you’ve got something truly depressing.

Publishers need to get out of this rut. The future is in networked text, multimedia and print on demand. Ebooks and their specialized hardware are a red herring.

Teleread also comments.

wall street journal on networked books and GAM3R 7H30RY

The Wall Street Journal has a big story today on networked books (unfortunately, behind a paywall). The article covers three online book experiments, Pulse, The Wealth of Networks, and GAM3R 7H30RY. The coverage is not particularly revelatory. What’s notable is that the press, which over the past decade-plus has devoted so much ink and so many pixels to ebooks, is now beginning to take a look at a more interesting idea. (“The meme is launched!” writes McKenzie.) Here’s the opening section:

Boundless Possibilities

As ‘networked’ books start to appear, consumers, publishers and authors get a glimpse of publishing to come

“Networked” books — those written, edited, published and read online — have been the coming thing since the early days of the Internet. Now a few such books have arrived that, while still taking shape, suggest a clearer view of the possibilities that lie ahead.

In a fairly radical turn, one major publisher has made a networked book available free online at the same time the book is being sold in stores. Other publishers have posted networked titles that invite visitors to read the book and post comments. One author has posted a draft of his book; the final version, he says, will reflect suggestions from his Web readers.

At their core, networked books invite readers online to comment on a written text, and more readers to comment on those comments. Wikipedia, the open-source encyclopedia, is the ultimate networked book. Along the way, some who participate may decide to offer up chapters translated into other languages, while still others launch Web sites where they foster discussion groups centered on essays inspired by the original text.

In that sense, networked books are part of the community-building phenomenon occurring all over the Web. And they reflect a critical issue being debated among publishers and authors alike: Does the widespread distribution of essentially free content help or hinder sales?

If the Journal would make this article available, we might be able to debate the question more freely.

the future of media companies

Every day we hear more reports about how media / hardware/ distribution companies are ever more frequently expanding horizontally (going into new categories) as well as vertically (going into more parts of their production/distribution chain).

In that, Amazon launched a download video service. MySpace opens a music store to compete with Apple’s iTunes and is also considering the creation of a print magazine. HarperCollins is selling downloadable media on their website. These are just a few examples.

What will the future of media publishing look like? How close are we from having only a few multi-national companies that produce the hardware, media and distribution? What are the other options?

Could the pendulum ever swing the other way? Could the future branded media company outsource all the creative, technology, publishing and distribution in a similar way that a laptop manufacturer has its mother board, processor, batteries, memory, drive, screen and advertising come from somewhere outside the company?

“a duopoly of Reuters-AP”: illusions of diversity in online news

Newswatch reports a powerful new study by the University of Ulster Centre for Media Research that confirms what many of us have long suspected about online news sources:

Through an examination of the content of major web news providers, our study confirms what many web surfers will already know – that when looking for reporting of international affairs online, we see the same few stories over and over again. We are being offered an illusion of information diversity and an apparently endless range of perspectives which in fact what is actually being offered is very limited information.

The appearance of diversity can be a powerful thing. Back in March, 2004, the McClatchy Washington Bureau (then Knight Ridder) put out a devastating piece revealing how the Iraqi National Congress (Ahmad Chalabi’s group) had fed dubious intelligence on Iraq’s WMDs not only to the Bush administration (as we all know), but to dozens of news agencies. The effect was a swarm of seemingly independent yet mutually corroborating reportage, edging American public opinion toward war.

A June 26, 2002, letter from the Iraqi National Congress to the Senate Appropriations Committee listed 108 articles based on information provided by the INC’s Information Collection Program, a U.S.-funded effort to collect intelligence in Iraq.

The assertions in the articles reinforced President Bush’s claims that Saddam Hussein should be ousted because he was in league with Osama bin Laden, was developing nuclear weapons and was hiding biological and chemical weapons.

Feeding the information to the news media, as well as to selected administration officials and members of Congress, helped foster an impression that there were multiple sources of intelligence on Iraq’s illicit weapons programs and links to bin Laden.

In fact, many of the allegations came from the same half-dozen defectors, weren’t confirmed by other intelligence and were hotly disputed by intelligence professionals at the CIA, the Defense Department and the State Department.

Nevertheless, U.S. officials and others who supported a pre-emptive invasion quoted the allegations in statements and interviews without running afoul of restrictions on classified information or doubts about the defectors’ reliability.

Other Iraqi groups made similar allegations about Iraq’s links to terrorism and hidden weapons that also found their way into official administration statements and into news reports, including several by Knight Ridder.

The repackaging of information goes into overdrive with the internet, and everyone, from the lone blogger to the mega news conglomerate, plays a part. Moreover, it’s in the interest of the aggregators and portals like Google and MSN to emphasize cosmetic or brand differences, so as to bolster their claims as indispensible filters for a tidal wave of news. So whether it’s Bush-Cheney-Chalabi’s WMDs or Google News’s “4,500 news sources updated continuously,” we need to maintain a skeptical eye.

***Related: myths of diversity in book publishing and large-scale digitization efforts.

the year-long Interdisciplinary Library Exhibit launches

The year-long Interdisciplinary Library Exhibit started last night at Proteus Gowanus, an arts organization located in Brooklyn, New York. The opening event was a standing room only presentation by Rick Prelinger and Megan Shaw Prelinger who run the Prelinger Library. Their presentation focused on their work leading up to the creation of the library, a highly curated collection of printed matter they have accumulated over two decades. The collection has a strong focus on books, print ephemera and periodicals. The 40,000 plus items are now on display and open to the public in downtown San Francisco. Visitors are allowed to stop in and browse items from the collection. The library’s collection is an amazing experiment in curation, taxonomy (they created their own,) and commentary on how libraries are shifting forms. We were fortunate to have lunch with Rick and Megan before their event. Everyone at the institute found their work very inspiring and they will be discussed in more detail in upcoming posts.

The year-long Interdisciplinary Library Exhibit started last night at Proteus Gowanus, an arts organization located in Brooklyn, New York. The opening event was a standing room only presentation by Rick Prelinger and Megan Shaw Prelinger who run the Prelinger Library. Their presentation focused on their work leading up to the creation of the library, a highly curated collection of printed matter they have accumulated over two decades. The collection has a strong focus on books, print ephemera and periodicals. The 40,000 plus items are now on display and open to the public in downtown San Francisco. Visitors are allowed to stop in and browse items from the collection. The library’s collection is an amazing experiment in curation, taxonomy (they created their own,) and commentary on how libraries are shifting forms. We were fortunate to have lunch with Rick and Megan before their event. Everyone at the institute found their work very inspiring and they will be discussed in more detail in upcoming posts.

The spirit of the Prelinger’s work is great introduction to Proteus Gowanus’ exploration on this theme. Libraries are in flux, as they have historically played many roles, including distributors of knowledge, places that support research, archives and now quite often, community centers. For the next year, Proteus Gowans is displaying in their gallery, artwork related to libraries as well as hosting presentations and films. Photos by Nina Katchadourian depict the spines of various books which compose textual messages. Artist Jeffrey Schiff’s contribution plays with the Dewey Decimal System and themes of categorizations by applying call numbers to everyday objects and spaces. Also, included in the exhibit is the Reanimation Library, curated and owned by Andrew Beccone. This collection preserves books that are not typically saved in public and academic libraries, including titles such as “Simplified Taxidermy,” “A Guide to Gymnastics” and “Judo: Thirty Lessons in the Modern Science of Jiu-Jitsu.” The next event is Deirdre Lawrence, the Principal Librarian and Coordinator of Research Services Museum Libraries and Archives at the Brooklyn Museum, on October 27th.

Issues of funding, the rise of the digital, and intellectual property are all changing the role of libraries and how people interact with them. Many large questions are being asked about the future of the library. The most basic one being, what will it look like? Will it start to shift towards smaller nodes of semi-private collections connected to each other via the network? Are collections of books going to be increasingly less tied to physical spaces? Will the public library continue to shift towards acting more like a community center? Are publishers and libraries going fuse and produce a new hybrid institution?

Realizing that libraries are going through a cultural as well as technological transformation, Proteus Gowanus is embarking on an year long examination in a variety of media which track these changes. They may not be able to answer any of these questions directly, but they are certainly providing new directions and understandings. Most importantly, the Interdisciplinary Library Exhibit is opening up the conversation to a diversity of voices, including the public at large.

google launches archival news search

Today Google unveiled a major extension of its news search service, expanding into periodical archives that stretch back to the mid-18th century. Most of the articles are pay downloads, or pay-per-view, and are offered by Google through licensing agreements with newspapers and existing document retrieval services including The New York Times Co., The Washington Post Co., The Wall Street Journal, Reed Elsevier, LexisNexis and Factiva. Google won’t actually host content or handle payments, it simply presents items with titles, brief excerpts and ordering information. Google also crawls free archives already on the web and mixes these in, and (a nice touch) links all search results to “related web pages,” plugging keywords into a general web search. Google won’t run adds in this service, at least for now. More coverage here and here.

This is a fine service, but it only underscores the need for a non-commercial alternative. Much of the material here is public domain, but is provided through commercial services. Google simply adds a new web-integrated layer. Anyone who believes that the public domain ought to be fully accessible to all should be thinking bigger than Google.

google flirts with image tagging

Ars Technica reports that Google has begun outsourcing, or “crowdsourcing,” the task of tagging its image database by asking people to play a simple picture labeling game. The game pairs you with a randomly selected online partner, then, for 90 seconds, runs you through a sequence of thumbnail images, asking you to add as many labels as come to mind. Images advance whenever you and your partner hit upon a match (an agreed-upon tag), or when you agree to take a pass.

Ars Technica reports that Google has begun outsourcing, or “crowdsourcing,” the task of tagging its image database by asking people to play a simple picture labeling game. The game pairs you with a randomly selected online partner, then, for 90 seconds, runs you through a sequence of thumbnail images, asking you to add as many labels as come to mind. Images advance whenever you and your partner hit upon a match (an agreed-upon tag), or when you agree to take a pass.

I played a few rounds but quickly grew tired of the bland consensus that the game encourages. Matches tend to be banal, basic descriptors, while anything tricky usually results in a pass. In other words, all the pleasure of folksonomies — splicing one’s own idiosyncratic sense of things with the usually staid task of classification — is removed here. I don’t see why they don’t open the database up to much broader tagging. Integrate it with the image search and harvest a bigger crop of metadata.

Right now, it’s more like Tom Sawyer tricking the other boys into whitewashing the fence. Only, I don’t think many will fall for this one because there’s no real incentive to participation beyond a halfhearted points system. For every matched tag, you and your partner score points, which accumulate in your Google account the more you play. As far as I can tell, though, points don’t actually earn you anything apart from a shot at ranking in the top five labelers, which Google lists at the end of each game. Whitewash, anyone?

In some ways, this reminded me of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, an “artificial artificial intelligence” service where anyone can take a stab at various HIT’s (human intelligence tasks) that other users have posted. Tasks include anything from checking business hours on restaurant web sites against info in an online directory, to transcribing podcasts (there are a lot of these). “Typically these tasks are extraordinarily difficult for computers, but simple for humans to answer,” the site explains. In contrast to the Google image game, with the Mechanical Turk, you can actually get paid. Fees per HIT range from a single penny to several dollars.

I’m curious to see whether Google goes further with tagging. Flickr has fostered the creation of a sprawling user-generated taxonomy for its millions of images, but the incentives to tagging there are strong and inextricably tied to users’ personal investment in the production and sharing of images, and the building of community. Amazon, for its part, throws money into the mix, which (however modest the sums at stake) makes Mechanical Turk an intriguing, and possibly entertaining, business experiment, not to mention a place to make a few extra bucks. Google’s experiment offers neither, so it’s not clear to me why people should invest.

on business models in web publishing

Here at the Institute, we’re generally more interested in thinking up new forms of publishing than in figuring out how to monetize them. But one naturally perks up at news of big money being made from stuff given away for free. Doc Searls points to a few items of such news.

First, that latest iteration of the American dream: blogging for big bucks, or, the self-made media mogul. Yes, a few have managed to do it, though I don’t think they should be taken as anything more than the exceptions that prove the rule that most blogs are smaller scale efforts in an ecology of niches, where success is non-monetary and more of the “nanofame” variety that iMomus, David Weinberger and others have talked about (where everyone is famous to fifteen people). But there is that dazzling handful of popular bloggers that rival the mass media outlets, and they’re raking in tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of dollars in ad revenues.

Some sites mentioned in the article:

— TechCrunch: “$60,000 in ad revenue every month” (not surprising — its right column devoted to sponsors is one of the widest I’ve seen)

— Boing Boing: “on track to gross an estimated $1 million in ad revenue this year”

— paidContent.org: over a million a year

— Fark.com: “on pace to become a multimillion-dollar property.

Then, somewhat surprisingly, is The New York Times. Handily avoiding the debacle predicted a year ago by snarky bloggers like myself when the paper decided to relocate its op-ed columnists and other distinctive content behind a pay wall, the Times has pulled in $9 million from nearly 200,000 web-exclusive Times Select subscribers, while revenues from the Times-owned About.com continue to skyrocket. There’s a feeling at the company that they’ve struck a winning formula (for now) and will see how long they can ride it:

When I ask if TimesSelect has been successful enough to suggest that more material be placed behind the wall, Nisenholtz [senior vice president for digital operations] replies, “The strategy isn’t to move more content from the free site to the pay site; we need inventory to sell to advertisers. The strategy is to create a more robust TimesSelect” by using revenue from the service to pay for more unique content. “We think we have the right formula going,” he says. “We don’t want to screw it up.”

***Subsequent thought: I’m not so sure. Initial indicators may be good, but I still think that the pay wall is a ticket to irrelevance for the Times’ columnists. Their readership is large and (for now) devoted enough to maintain the modestly profitable fortress model, but I think we’ll see it wither over time.***

Also, in the Times, there’s this piece about ad-supported wiki hosting sites like Wikia, Wetpaint, PBwiki or the swiftly expanding WikiHow, a Wikipedia-inspired how-to manual written and edited by volunteers. Whether or not the for-profit model is ultimately compatible with the wiki work ethic remains to be seen. If it’s just discrete ads in the margins that support the enterprise, then contributors can still feel to a significant extent that these are communal projects. But encroach further and people might begin to think twice about devoting their time and energy.

***Subsequent thought 2: Jesse made an observation that makes me wonder again whether the Times Company’s present success (in its present framework) may turn out to be short-lived. These wiki hosting networks are essentially outsourcing, or “crowdsourcing” as the latest jargon goes, the work of the hired About.com guides. Time will tell which is ultimately the more sustainable model, and which one will produce the better resource. Given what I’ve seen on About.com, I’d place my bets on the wikis. The problem? You, or your community, never completely own your site, so you’re locked into amateur status. With Wikipedia, that’s the point. But can a legacy media company co-opt so many freelancers without pay? These are drastically different models. We’re probably not dealing with an either/or here.***

We’ve frequently been asked about the commercial potential of our projects — how, for instance, something like GAM3R 7H30RY might be made to make money. The answer is we don’t quite know, though it should be said that all of our publishing experiments have led to unexpected, if modest, benefits — bordering on the financial — for their authors. These range from Alex selling some of his paintings to interested commenters at IT IN place, to Mitch gradually building up a devoted readership for his next book at Without Gods while still toiling away at the first chapter, to McKenzie securing a publishing deal with Harvard within days of the Chronicle of Higher Ed. piece profiling GAM3R 7H30RY (GAM3R 7H30RY version 1.2 will be out this spring, in print).

Build up the networks, keep them open and toll-free, and unforseen opportunities may arise. It’s long worked this way in print culture too. Most authors aren’t making a living off the sale of their books. Writing the book is more often an entree into a larger conversation — from the ivory tower to the talk show circuit, and all points in between. With the web, however, we’re beginning to see the funnel reversed: having the conversation leads to writing the book. At least in some cases. At this point it’s hard to trace what feeds into what. So many overlapping conversations. So many overlapping economies.