![]() Another funny thing about Larry Sanger’s idea of a progressive fork off of Wikipedia is that he can do nothing, under the terms of the Free Documentation License, to prevent his expert-improved content from being reabsorbed by Wikipedia. In other words, the better the Citizendium becomes, the better Wikipedia becomes — but not vice versa. In the Citizendium (the name still refuses to roll off the tongue), forks are definitive. The moment a new edit is made, an article’s course is forever re-charted away from Wikipedia. So, assuming anything substantial comes of the Citizendium, feeding well-checked, better written content to Wikipedia could end up being its real value. But would it be able to sustain itself under such uninspiring circumstances? The result might be that the experts themselves fork back as well.

Another funny thing about Larry Sanger’s idea of a progressive fork off of Wikipedia is that he can do nothing, under the terms of the Free Documentation License, to prevent his expert-improved content from being reabsorbed by Wikipedia. In other words, the better the Citizendium becomes, the better Wikipedia becomes — but not vice versa. In the Citizendium (the name still refuses to roll off the tongue), forks are definitive. The moment a new edit is made, an article’s course is forever re-charted away from Wikipedia. So, assuming anything substantial comes of the Citizendium, feeding well-checked, better written content to Wikipedia could end up being its real value. But would it be able to sustain itself under such uninspiring circumstances? The result might be that the experts themselves fork back as well.

Monthly Archives: September 2006

adobe acrobat 8 is probably not for you

Adobe just announced the release of Acrobat 8, their PDF production software. To promote it, they hosted three “webinars” on Tuesday to demonstrate some of the new features to the interested public. Your correspondent was there (well, here) to see what glimmers might be discerned about the future of electronic reading.

Who cares about Acrobat?

What does Acrobat have to do with electronic books? You’re probably familiar with Acrobat Reader: it’s the program that opens up PDFs. Acrobat is the “author” program: it lets people make PDFs. This is very important in the world of print design and publishing: probably 90% of the new printed material you see every day goes through Acrobat in some form or another. Acrobat’s not quite as ubiquitous as it once was – newer programs like Adobe InDesign, for example, let designers create PDFs that can be sent to the printer’s without bothering with Acrobat, and it’s easy to make PDFs out of anything in Mac OS X. But Acrobat remains an enormous force in the world of print design.

PDF, of course, has been presented as being a suitable format for electronic books; see here for an example. Acrobat provided the ability for publishers to lock down the PDFs that Amazon (for example) sold with DRM; publishers jumped on board. The system wasn’t successful, not least because opening the locked PDFs proved chancey: I have a couple of PDFs I bought during Amazon’s experiment selling them which, on opening, download a lot of “verification information” and then give inscrutable errors. In part because of these troubles, Amazon’s largely abandoned the format – notice their sad-looking ebook store.

Why keep an eye on Acrobat? One reason is because Acrobat 8 is Adobe’s first major release since merging with Macromedia, a union that sent shockwaves across the world of print and web design. Adobe now releases almost most significant programs used in print design. (A single exception is Quark XPress, which has been quietly rolling away towards oblivion of its own accord since around the millennium.) With the acquisition of Macromedia’s web technologies – including Flash and Dreamweaver – Adobe is inching towards a Microsoft-style monopoly of Web design. In short: where Acrobat goes is where Adobe goes; and where Adobe goes is where design goes. And where design goes is where books go, maybe.

So what does Acrobat 8 do?

Acrobat 8 provides a number of updated features that will be useful to people who do pre-press and probably uninteresting to anyone else. They’ve made a number of minor improvements – the U. S. government will be happy to know that they can now use Acrobat to redact information without having to worry about the press looking under their black boxes. You can now use Acrobat to take a bunch of documents (PDF or otherwise) and lump them together into a “bundle”. All nice things, but nothing to get excited about. More DRM than you could shake a stick at, but that’s to be expected.

The most interesting thing that Acrobat 8 does – and the reason I’m bringing this up here – is called Acrobat Connect. Acrobat Connect allows users to host web conferences around a document – it was what Adobe was using to hold their “webinars”. (There’s a screenshot to the right; click on the thumbnail for the full-sized image.) These conferences can be joined by anyone with an Internet connection and the Flash plugin. Pages can be turned and annotations can be made by those with sufficient privileges. Audio chatting is available, as is text-based chatting. The whole “conversation” can be recorded for future reference as a Flash-based movie file.

The most interesting thing that Acrobat 8 does – and the reason I’m bringing this up here – is called Acrobat Connect. Acrobat Connect allows users to host web conferences around a document – it was what Adobe was using to hold their “webinars”. (There’s a screenshot to the right; click on the thumbnail for the full-sized image.) These conferences can be joined by anyone with an Internet connection and the Flash plugin. Pages can be turned and annotations can be made by those with sufficient privileges. Audio chatting is available, as is text-based chatting. The whole “conversation” can be recorded for future reference as a Flash-based movie file.

There are a lot of possibilities that this technology suggests: take an electronic book as your source text and you could have an electronic book club. Teachers could work their way through a text with students. You could use it to copy-edit a book that’s being published. A group of people could get together to argue about a particularly interesting blog post. Reading could become a social experience.

But what’s the catch?

There’s one catch, and it’s a big one: the infrastructure that Acrobat 8 uses: you have to use Adobe’s server, and there’s a price for that. It was suggested that chat-hosting access would be provided for $39 a month or $395 a year. This isn’t entirely a surprise: more and more software companies are trying to rope consumers into subscription-based models. This might well work for Adobe: I’m sure there are plenty of corporations that won’t balk at shelling out $395 a year for what Acrobat Connect offers (plus $449 for the software). Maybe some private schools will see the benefit of doing that. But I can’t imagine, however, that there are going to be many private individuals who will. Much as I’d like to, I won’t.

I’m not faulting Adobe for this stance: they know who butters their bread. But I think it’s worth noting what’s happening here: a divide between the technology available to the corporate world and the general public, and, more specifically, a divide that doesn’t need to exist. Though they don’t have the motive to do so, Adobe could presumably make a version of Acrobat Connect that would work on anyone’s server. This would open up a new realm of possibility in the world of online reading. Instead, what’s going to happen is that the worker bees of the corporate world will find themselves forced to sit through more PowerPoint presentations at their desks.

While a bunch of people reading PowerPoint could be seen as a social reading experience, so much more is possible. We, the public, should be demanding more out of our software.

a fork in the road II: shirky on citizendium

Clay Shirky has some interesting thoughts on why Larry Sanger’s expert-driven Wikipedia spinoff Citizendium is bound to fail. At the heart of it is Sanger’s notion of expertise, which is based largely on institutional warrants like academic credentials, yet lacks in Citizendium the institutional framework to effectively impose itself. In other words, experts are “social facts” that rely on culturally manufactured perceptions and deferences, which may not be transferrable to an online project like the Citizendium. Sanger envisions a kind of romance between benevolent academics and an adoring public that feels privileged to take part in a distributed apprenticeship. In reality, Shirky says, this hybrid of Wikipedia-style community and top-down editorial enforcement is likely to collapse under its own contradictions. Shirky:

Citizendium is based less on a system of supportable governance than on the belief that such governance will not be necessary, except in rare cases. Real experts will self-certify; rank-and-file participants will be delighted to work alongside them; when disputes arise, the expert view will prevail; and all of this will proceed under a process that is lightweight and harmonious. All of this will come to naught when the citizens rankle at the reflexive deference to editors; in reaction, they will debauch self-certification…contest expert preogatives, rasing the cost of review to unsupportable levels…take to distributed protest…or simply opt-out.

Shirky makes a point at the end of his essay that I found especially insightful. He compares the “mechanisms of deference” at work in Wikipedia and in the proposed Citizendium. In other words, how in these two systems does consensus crystallize around an editorial action? What makes people say, ok, I defer to that?

The philosophical issue here is one of deference. Citizendium is intended to improve on Wikipedia by adding a mechanism for deference, but Wikipedia already has a mechanism for deference — survival of edits. I recently re-wrote the conceptual recipe for a Menger Sponge, and my edits have survived, so far. The community has deferred not to me, but to my contribution, and that deference is both negative (not edited so far) and provisional (can always be edited.)

Deference, on Citizendium will be for people, not contributions, and will rely on external credentials, a priori certification, and institutional enforcement. Deference, on Wikipedia, is for contributions, not people, and relies on behavior on Wikipedia itself, post hoc examination, and peer-review. Sanger believes that Wikipedia goes too far in its disrespect of experts; what killed Nupedia and will kill Citizendium is that they won’t go far enough.

My only big problem with this piece is that it’s too easy on Wikipedia. Shirky’s primary interest is social software, so the big question for him is whether a system will foster group interaction — Wikipedia’s has proven to do so, and there’s reason to believe that Citizendium’s will not, fair enough. But Shirky doesn’t acknowledge the fact that Wikipedia suffers from some of the same problems that he claims will inevitably plague Citizendium, the most obvious being insularity. Like it or not, there is in Wikipedia de facto top-down control by self-appointed experts: the cliquish inner core of editors that over time has becomes increasingly hard to penetrate. It’s not part of Wikipedia’s policy, it certainly goes against the spirit of the enterprise, but it exists nonetheless. These may not be experts as defined by Sanger, but they certainly are “social facts” within the Wikipedia culture, and they’ve even devised semi-formal credential systems like barnstars to adorn their user profiles and perhaps cow more novice users. I still agree with Shirky’s overall prognosis, but it’s worth thinking about some of the problems that Sanger is trying to address, albeit in a misconceived way.

a fork in the road for wikipedia

Estranged Wikipedia cofounder Larry Sanger has long argued for a more privileged place for experts in the Wikipedia community. Now his dream may finally be realized. A few days ago, he announced a new encyclopedia project that will begin as a “progressive fork” off of the current Wikipedia. Under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, anyone is free to reproduce and alter content from Wikipedia on an independent site as long as the new version is made available under those same terms. Like its antecedent, the new Citizendium, or “Citizens’ Compendium”, will rely on volunteers to write and develop articles, but under the direction of self-nominated expert subject editors. Sanger, who currently is in the process of recruiting startup editors and assembling an advisory board, says a beta of the site should be up by the end of the month.

We want the wiki project to be as self-managing as possible. We do not want editors to be selected by a committee, which process is too open to abuse and politics in a radically open and global project like this one is. Instead, we will be posting a list of credentials suitable for editorship. (We have not constructed this list yet, but we will post a draft in the next few weeks. A Ph.D. will be neither necessary nor sufficient for editorship.) Contributors may then look at the list and make the judgment themselves whether, essentially, their CVs qualify them as editors. They may then go to the wiki, place a link to their CV on their user page, and declare themselves to be editors. Since this declaration must be made publicly on the wiki, and credentials must be verifiable online via links on user pages, it will be very easy for the community to spot false claims to editorship.

We will also no doubt need a process where people who do not have the credentials are allowed to become editors, and where (in unusual cases) people who have the credentials are removed as editors. (link)

Initially, this process will be coordinated by “an ad hoc committee of interim chief subject editors.” Eventually, more permanent subject editors will be selected through some as yet to be determined process.

Another big departure from Wikipedia: all authors and editors must be registered under their real name.

More soon…

Reports in Ars Technica and The Register.

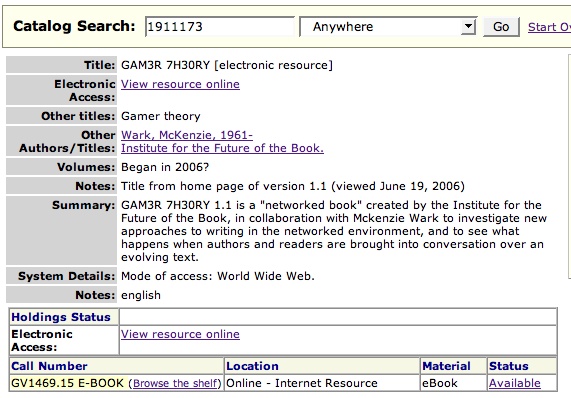

GAM3R 7H30RY found in online library catalog

Here’s a wonderful thing I stumbled across the other day: GAM3R 7H30RY has its very own listing in North Carolina State University’s online library catalog.

The catalog is worth browsing in general. Since January, it’s been powered by Endeca, a fantastic library search tool that, among many other things, preserves some of the serendipity of physical browsing by letting you search the shelves around your title.

(Thanks, Monica McCormick!)

perelman’s proof / wsj on open peer review

Last week got off to an exciting start when the Wall Street Journal ran a story about “networked books,” the Institute’s central meme and very own coinage. It turns out we were quoted in another WSJ item later that week, this time looking at the science journal Nature, which over the summer has been experimenting with opening up its peer review process to the scientific community (unfortunately, this article, like the networked books piece, is subscriber only).

I like this article because it smartly weaves in the story of Grigory (Grisha) Perelman, which I had meant to write about earlier. Perelman is a Russian topologist who last month shocked the world by turning down the Fields medal, the highest honor in mathematics. He was awarded the prize for unraveling a famous geometry problem that had baffled mathematicians for a century.

I like this article because it smartly weaves in the story of Grigory (Grisha) Perelman, which I had meant to write about earlier. Perelman is a Russian topologist who last month shocked the world by turning down the Fields medal, the highest honor in mathematics. He was awarded the prize for unraveling a famous geometry problem that had baffled mathematicians for a century.

There’s an interesting publishing angle to this, which is that Perelman never submitted his groundbreaking papers to any mathematics journals, but posted them directly to ArXiv.org, an open “pre-print” server hosted by Cornell. This, combined with a few emails notifying key people in the field, guaranteed serious consideration for his proof, and led to its eventual warranting by the mathematics community. The WSJ:

…the experiment highlights the pressure on elite science journals to broaden their discourse. So far, they have stood on the sidelines of certain fields as a growing number of academic databases and organizations have gained popularity.

One Web site, ArXiv.org, maintained by Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., has become a repository of papers in fields such as physics, mathematics and computer science. In 2002 and 2003, the reclusive Russian mathematician Grigory Perelman circumvented the academic-publishing industry when he chose ArXiv.org to post his groundbreaking work on the Poincaré conjecture, a mathematical problem that has stubbornly remained unsolved for nearly a century. Dr. Perelman won the Fields Medal, for mathematics, last month.

(Warning: obligatory horn toot.)

“Obviously, Nature’s editors have read the writing on the wall [and] grasped that the locus of scientific discourse is shifting from the pages of journals to a broader online conversation,” wrote Ben Vershbow, a blogger and researcher at the Institute for the Future of the Book, a small, Brooklyn, N.Y., , nonprofit, in an online commentary. The institute is part of the University of Southern California’s Annenberg Center for Communication.

Also worth reading is this article by Sylvia Nasar and David Gruber in The New Yorker, which reveals Perelman as a true believer in the gift economy of ideas:

Perelman, by casually posting a proof on the Internet of one of the most famous problems in mathematics, was not just flouting academic convention but taking a considerable risk. If the proof was flawed, he would be publicly humiliated, and there would be no way to prevent another mathematician from fixing any errors and claiming victory. But Perelman said he was not particularly concerned. “My reasoning was: if I made an error and someone used my work to construct a correct proof I would be pleased,” he said. “I never set out to be the sole solver of the Poincaré.”

Perelman’s rejection of all conventional forms of recognition is difficult to fathom at a time when every particle of information is packaged and owned. He seems almost like a kind of mystic, a monk who abjures worldly attachment and dives headlong into numbers. But according to Nasar and Gruber, both Perelman’s flouting of academic publishing protocols and his refusal of the Fields medal were conscious protests against what he saw as the petty ego politics of his peers. He claims now to have “retired” from mathematics, though presumably he’ll continue to work on his own terms, in between long rambles through the streets of St. Petersburg.

Regardless, Perelman’s case is noteworthy as an example of the kind of critical discussions that scholars can now orchestrate outside the gate. This sort of thing is generally more in evidence in the physical and social sciences, but ought too to be of great interest to scholars in the humanities, who have only just begun to explore the possibilities. Indeed, these are among our chief inspirations for MediaCommons.

Academic presses and journals have long functioned as the gatekeepers of authoritative knowledge, determining which works see the light of day and which ones don’t. But open repositories like ArXiv have utterly changed the calculus, and Perelman’s insurrection only serves to underscore this fact. Given the abundance of material being published directly from author to public, the critical task for the editor now becomes that of determining how works already in the daylight ought to be received. Publishing isn’t an endpoint, it’s the beginning of a process. The networked press is a guide, a filter, and a discussion moderator.

Nature seems to grasp this and is trying with its experiment to reclaim some of the space that has opened up in front of its gates. Though I don’t think they go far enough to effect serious change, their efforts certainly point in the right direction.

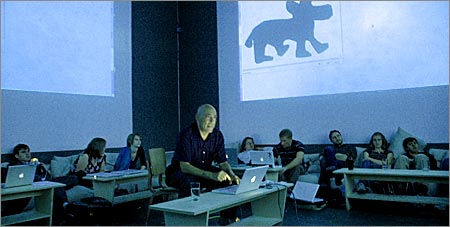

carleton roadtrip begins at the institute

On Wednesday, we had the pleasure of spending an afternoon with a group of 22 students from Carleton College who are spending a trimester studying and making digital media under the guidance of John Schott, a professor in the Dept. of Cinema & Media Studies specializing in “personal media” production and network culture. This year, his class is embarking on an off-campus study, a ten-week odyssey beginning in Northfield, Minnesota and taking them to New York, London, Amsterdam and Berlin. At each stop, they’ll be visiting with new media producers, attending festivals and exhibitions, and documenting their travels in a variety of forms. Needless to say, we’re deeply envious.

The Institute was the first stop on their trip, so we tried to start things off with a flourish. After a brief peak at the office, we brought the class over to Monkeytown, a local cafe and video club with a fantastic cube-shaped salon in the back where gigantic projection screens hang on each of the four walls.

Hooking our computers up to the projectors, we took the students on a tour of what we do: showed them our projects, talked about networked books (it was surreal to see GAM3R 7H30RY blown up 20 feet wide, wavering slightly in the central AC), and finished with a demo of Sophie. John Schott wrote a nice report about our meeting on the class’s blog. Also, for a good introduction to John’s views on personal media production and media literacy, take a look at this interview he gave on a Minnesota video blog back in March.

This is a great group of students he’s assembled, with interests ranging from film production to philosophy to sociology. They also seem to like Macs. This could be an ad for the new MacBook:

We’ve invited them back toward the end of their three weeks in New York to load Sophie onto their laptops before they head off to Europe.

(photos by John Schott)

some thoughts on mapping

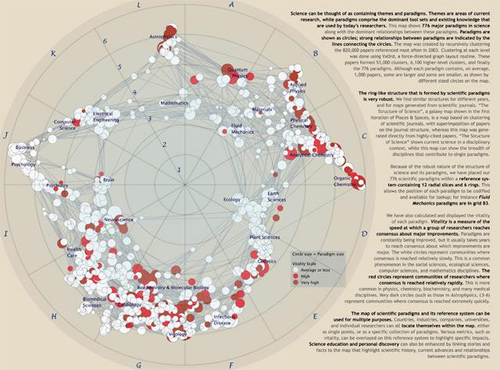

Mapping is a useful abstraction for exploring ideas, and not just for navigation through the physical world. A recent exhibit, Places & Spaces: Mapping Science, (at the New York Public Library of Science, Industry, and Business), presented maps that render the invisible path of scientific progress using metaphors of cartography. The maps ranged in innovation: there were several that imitated traditional geographical and topographical maps, while others created maps based on nodal presenation—tree maps and hyperbolic radial maps. Nearly all relied on citation analysis for the data points. Two interesting projects: Brad Paley’s TextArc Visualization of “The History of Science”, which maps scientific progress as described in the book “The History of Science”; and Ingo Gunther’s Worldprocessor Globes, which are perfectly idiosyncratic in their focus.

But, to me, the exhibit highlighted a fundamental drawback of maps. Every map is an incomplete view of an place or a space. The cartographer makes choices about what information to include, but more significantly, what information to leave out. Each map is a reflection of the cartographer’s point of view on the world in question.

Maps serve to guide—whether from home to a vacation house in the next state, or from the origin of genetic manipulation through to the current replication practices stem-cell research. In physical space, physical objects circumscribe your movement through that space. In mental space, those constraints are missing. How much more important is it, then, to trust your guide, and understand the motivations behind your map? I found myself thinking that mapping as a discipline has the same lack of transparency as traditional publishing.

How do we, in the spirit of exploration, maintain the useful art of mapping, yet expand and extend mapping for the networked age? The network is good at bringing information to people, and collecting feedback. A networked map would have elements of both information sharing, and information collection, in a live, updateable interface. Jeff Jarvis has discussed this idea already in his post on networked mapping. Jarvis proposes mashing up Google maps (or open street map) with other software to create local maps, by and for the community.

This is an excellent start (and I hope we’ll see integration of mapping tools in the near future), but does this address the limitations of cartographic editing? What I’m thinking about is something less like a Google map, and more like an emergent terrain assembled from ground-level and satellite photos, walks, contributed histories, and personal memories. Like the Gates Memory Project we did last year, this space would be derived from the aggregate, built entirely without the structural impositions of a predetermined map. It would have a Borgesian flavor; this derived place does not have to be entirely based on reality. It could include fantasies or false memories of a place, descriptions that only exists in dreams. True, creating a single view of such a map would come up against the same problems as other cartographic projects. But a digital map has the ability to reveal itself in layers (like old acetate overlays did for elevation, roads, and buildings). Wouldn’t it be interesting to see what a collective dreamscape of New York looked like? And then to peel back the layers down to the individual contributions? Instead of finding meaning through abstraction, we find meaningful patterns by sifting through the pile of activity.

We may never be able to collect maps of this scale and depth, but we will be able to see what a weekend of collective psychogeography can produce at the Conflux Festival, which opened yesterday in locations around NYC. The Conflux Festival (formerly the Psychogeography Festival) is “the annual New York festival for contemporary psychogeography, the investigation of everyday urban life through emerging artistic, technological and social practice.” It challenges notions of public and private space, and seeks out areas of exploration within and at the edges of our built environment. It also challenges us, as citizens, to be creative and engaged with the space we inhabit. With events going on in the city simultaneously at various locations, and a team of students from Carleton college recording them, I hope we’ll end up with a map composed of narrative as much as place. Presented as audio- and video-rich interactions within specific contexts and locations in the city, I think it will give us another way to think about mapping.

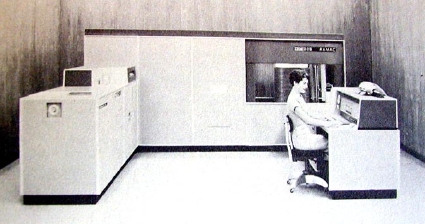

the march of technology

Sept. 13, 1956

IBM’s 5MegaByte hard drive, is the size of two refrigerators and costs $50,000.

Feb. 13, 2006

Seagate’s 12GigaByte hard drive, will fit in your cell phone.

Sept. 13, 2006

50 years later: 200 times more storage than the IBM drive on something smaller than a postage stamp. (Size: 11mm widex 15mm long x 1mm tall).

(thanks to endgadget)

wikipedia-britannica debate

The Wall Street Journal the other day hosted an email debate between Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales and Encyclopedia Britannica editor-in-chief Dale Hoiberg. Irreconcilible differences, not surprisingly, were in evidence. ![]()

![]() But one thing that was mentioned, which I had somehow missed recently, was a new governance experiment just embarked upon by the German Wikipedia that could dramatically reduce vandalism, though some say at serious cost to Wikipedia’s openness. In the new system, live pages will no longer be instantaneously editable except by users who have been registered on the site for a certain (as yet unspecified) length of time, “and who, therefore, [have] passed a threshold of trustworthiness” (CNET). All edits will still be logged, but they won’t be reflected on the live page until that version has been approved as “non-vandalized” by more senior administrators. One upshot of the new German policy is that Wikipedia’s front page, which has long been completely closed to instantaneous editing, has effectively been reopened, at least for these “trusted” users.

But one thing that was mentioned, which I had somehow missed recently, was a new governance experiment just embarked upon by the German Wikipedia that could dramatically reduce vandalism, though some say at serious cost to Wikipedia’s openness. In the new system, live pages will no longer be instantaneously editable except by users who have been registered on the site for a certain (as yet unspecified) length of time, “and who, therefore, [have] passed a threshold of trustworthiness” (CNET). All edits will still be logged, but they won’t be reflected on the live page until that version has been approved as “non-vandalized” by more senior administrators. One upshot of the new German policy is that Wikipedia’s front page, which has long been completely closed to instantaneous editing, has effectively been reopened, at least for these “trusted” users.

In general, I believe that these sorts of governance measures are a sign not of a creeping conservatism, but of the growing maturity of Wikipedia. But it’s a slippery slope. In the WSJ debate, Wales repeatedly assails the elitism of Britannica’s closed editorial model. But over time, Wikipedia could easily find itself drifting in that direction, with a steadily hardening core of overseers exerting ever tighter control. Of course, even if every single edit were moderated, it would still be quite a different animal from Britannica, but Wales and his council of Wikimedians shouldn’t stray too far from what made Wikipedia work in the first place, and from what makes it so interesting.

In a way, the exchange of barbs in the Wales-Hoiberg debate conceals a strange magnetic pull between their respective endeavors. Though increasingly seen as the dinosaur, Britannica has made small but not insignificant moves toward openess and currency on its website (Hoiberg describes some of these changes in the exchange), while Wikipedia is to a certain extent trying to domesticate itself in order to attain the holy grail of respectability that Britannica has long held. Think what you will about Britannica’s long-term prospects, but it’s a mistake to see this as a clear-cut story of violent succession, of Wikipedia steamrolling Britannica into obsolescence. It’s more interesting to observe the subtle ways in which the two encyclopedias cause each other to evolve.

Wales certainly has a vision of openness, but he also wants to publish the world’s best encyclopedia, and this includes releasing something that more closely resembles a Britannica. Back in 2003, Wales proposed the idea of culling Wikipedia’s best articles to produce a sort of canonical version, a Wikipedia 1.0, that could be distributed on discs and printed out across the world. Versions 1.1, 1.2, 2.0 etc. would eventually follow. This is a perfectly good idea, but it shouldn’t be confused with the goals of the live site. I’m not saying that the “non-vandalized” measure was constructed specifically to prepare Wikipedia for a more “authoritative” print edition, but the trains of thought seem to have crossed. Marking versions of articles as non-vandalized, or distinguishing them in other ways, is a good thing to explore, but not at the expense of openness at the top layer. It’s that openness, crazy as it may still seem, that has lured millions into this weird and wonderful collective labor.