Last Tuesday I was formally introduced to Sophie. Our first date left me dazed and confused. She is a powerful multimedia application from New York, well funded and growing under healthy cosmopolitan influences, while I am a digitally challenged graduate student with a dreadful Third World education.  Despite the obvious mismatch, Sophie was surprisingly responsive. For a program that is still a month away from even entering beta purgatory, to freeze up once in a while is perfectly normal. My reaction, on the other hand, was childish and immature. I protested out loud, argued with developers, worried about details, and became permanently infatuated. Now I can’t stop thinking about Sophie.

Despite the obvious mismatch, Sophie was surprisingly responsive. For a program that is still a month away from even entering beta purgatory, to freeze up once in a while is perfectly normal. My reaction, on the other hand, was childish and immature. I protested out loud, argued with developers, worried about details, and became permanently infatuated. Now I can’t stop thinking about Sophie.

The problem is that she lies at the core of everything I want to do. During the next couple of decades I would like to participate in the collaborative development of multimedia ecosystems. Ok, that sounds awfully pretentious. What I really want is to work and play with a bunch of friends in a huge toy factory. My favorite toys are multimedia creatures.

For a while (and halfway-tongue-in-cheek) I have been training myself to think about all kinds of cultural artifacts in evolutionary terms. When I play around with a good old printed book, for example, I try to think about it as a potentially feature-rich creature that, so far as I am concerned, is working very well in frozen text mode. All other noisier and flashier possible forms of behavior have been muted, so to speak, in order to maximize the cultural value of the reading experience.

I think Sophie fascinates me precisely because her future depends so much on achieving a creative balance between simplicity and complexity. If everything goes well, Sophie will be able to handle very intricate tasks in rather plain terms. The program already has an unobtrusive but intuitive interface that would allow first time users to assemble rich multimedia documents in a matter of minutes. A highly sophisticated Sophie document can be embedded as a whole into another Sophie document. Placing an entire library of interconnected multimedia artifacts in a corner of a page within a Sophie “book” would only take a few mouse clicks.

An open source multimedia assembling program is always welcome. Sophie will be particularly good at doing difficult things the easy way, and that is a bonus in an industry cluttered with “advanced” applications that seem to be going in the opposite direction. Given the proper planetary alignment, a nurturing community could grow around the development of extensions and additions to the program. Eventually, Sophie would be unrecognizable, and that is the best thing that can happen to an evolving living thing.

Did I mention that the application has also been conceived as a platform independent application for collaborative multimedia assembling? That’s right; Sophie would eventually allow people to join efforts in authoring and managing complex documents over a network. These are my kind of toys: evolving multimedia artifacts, born on a network, raised by a virtual village, and assembled with a tool that is being develop along similar principles. Very cool stuff.

Strategically speaking, however, the development of Sophie, and the model of collaborative multimedia creation in general, could be better implemented using the notion of software as a service. Downloading an application that would reside in the desktop and then using it to handle files over a network is relatively cumbersome. This model requires periodic updating of the program and a high volume of general traffic up and down the servers.

Under the current paradigm, Sophie is being developed just like Microsoft Word but I would rather work on something more along the lines of Writely. An Ajax-based version of Sophie within a regular web browser like Firefox would maximize the networking capabilities of the application. Full assembly functionality could be hard to achieve this way, but in a tradeoff between fancy multimedia features and wider potential for collaboration I would tend to favor the latter. The evolutionary success of a networked book will depend on the qualities of the network rather than the features of the book.

Online collaboration can be achieved more efficiently by sideloading rather than constantly uploading and downloading files. In an ideal world we would only need to upload original raw files, and only once. Everything else would happen at the server level. Every user would have access to every file and any combination of files at every step during the assembling process, from any computer connected to the internet.

This late in its development, altering the nature of an application like Sophie at this radical level is too difficult. Perhaps the best way to go about it is to release a beta version of the program, in order to broaden its community of developers, and hope that a team of Ajax-savvy people decides to create a browser-based alternative interface for Sophie. In the meantime she should consider setting up a series of dates with the guys at Ajax13. I promise I won’t be jealous.

Monthly Archives: August 2006

“highbrow” video games?

Recently in the gaming blog Gamersutra, Ernest Adams questions why aren’t there highbrow video games.” His article comes one month after an Esquire article, where Chuck Klosterman wondered why isn’t there good video game criticism and makes the claim that video games needs its own Lester Bangs. As the video game market grows, it is not surprising that fans and advocates of gaming will want to form to grow and mature as well.

Recently in the gaming blog Gamersutra, Ernest Adams questions why aren’t there highbrow video games.” His article comes one month after an Esquire article, where Chuck Klosterman wondered why isn’t there good video game criticism and makes the claim that video games needs its own Lester Bangs. As the video game market grows, it is not surprising that fans and advocates of gaming will want to form to grow and mature as well.

Adams’ call for “highbrow” games is rooted in a desire to add creditability and legitimacy to video games. As someone who has dedicated his career to making and writing about video games, the never-ending criticism about the violence in games by various groups looking for easy political targets must be frustrating to endure. I can appreciate the motivations behind Adam’s conclusion, however, his description of highbrow video games is ultimately too narrowly defined and overlooks impressive experiments of video games.

I hesitate to even try to deem games “high” or “low” because the terms are not that useful. Adams specifically points out that the films he aspires video games to emulate are not “art films,” which he describes as a “short low-budget titles filled with impenetrable weirdness.” Therefore, his definition of highbrow edge towards the problematic “I know it when I see it” definitions of art. Further, we can gather insight on culture and ourselves by interacting will both high and low culture and valuing one form over another is problematic.

From his description of a highbrow video game, I think what Adams is really asking for is better interactive narratives in gaming. He alludes to the films of Ishmail Merchant and James Ivory, who are best known for adopting the novels of E.M. Forester, often with screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. Their films tend to be beautiful, well crafted analyses of class. Although, they are not generally know for pushing the boundaries of film.

Last year, Adams gave a talk which he published on his website, in which he assesses the state of interactive narrative. It provides more insight on his train of thought. In it, one of his references in video game scholarship is Janet Murray’s Hamlet on the Holodeck which uses a theatrical frame of reference in postulating the future of interactive narrative. Also, Adams offers a model of a “structured” approach to the narrative of video games and reveals that he is particularly wedded to the idea of single player games over the shared gaming experience of MMORPGs which are increasingly popular. In his current essay, his description of states that the highbrow video game “would reward close attention and playing more than once.” This implies that he still leans towards single player role playing games in his conceptualization of highbrow games.

However, video games that are pushing the form in more “artistic” ways are occurring outside the bounds of single player game. For example, we-make-money-not-art reported on The Endless Forest, which is a gorgeous MMORPG in which players assume the identity of a deer. Developed by the Belgian studio Tale of Tales, The Endless Forest has an elegant interface and darkly rich art direction. Although it lacks an explicit narrative, the gameplay engages users without the typical violence and sexually charged themes of many games. The Endless Forest limits the use of language. Therefore, it does not include a chat function and players are “named” with pictograms rather than words. However, as more of these kinds of games are created, they are unlikely to lessen the criticism of the negative social effects of video games.

As for criticism, the notion of elevating video game criticism to a higher form is rather ironic, as it comes at the same time when the New York Times critic A.O. Scott finds himself defending film criticism. While not a music critic, Scott describes the critics’ predicament that often panned movies are still hugh box offices successes. Media critics want the new and interesting, which is somewhat expected if it is your job to watch and write about movies, music, or video games everyday. Their standards are quite different from the typical audience member. Lester Bangs was a polarizing figure, who wanted to raise the standards of writing on music. He appeared at a time when people were ready for similar standards. It may be that a critical mass of audience for a similar kind of criticism for gaming is beginning to emerge.

As previously stated, most gamers will still want “mainstream” titles. Because games are expensive, they will still rely on criticism which Klosterman dismissives as “customer advice.” That is, many gamers, if not most, will still mostly be interested in reading reviews which describe gameplay, graphics and sound design, rather than thematic and issues of meaning. Many gamers don’t like the academic scholarly writing on video games, which is in adbundance, but is not what Klosterman wants to read. We learned about their attitutdes in initial reactions and comments posted across the gaming blogosphere about our project “GAM3R 7H30RY.” It’s not clear to me what is bad about gaming publications serving the desires of the video game playing community.

My guess is that both boundary pushing video games and criticism will be begin to get more exposure fairly soon. For the actual video games, I would look towards Europe and Asia, where more government funding exists for developing these kinds of endeavors. I don’t expect many of the big gaming companies in the US to create experimental games of this nature. Although, they might in the future, after the proven economic viability of them. In that, major movie studios started funding more smaller films after they saw successful crossover of films of the Merchant Ivory variety. Although, Rockstar (the maker of Grand Theft Auto) have the upcoming and already controversial game Bully, where you must navigate a boarding school as a new student. It was described by the New York TImes as having, “an open world for the players to explore, tightly defined and memorable characters, a strong story line, [and] high-end voice acting,” which is precisely what Adams call for in his article.

My guess is that both boundary pushing video games and criticism will be begin to get more exposure fairly soon. For the actual video games, I would look towards Europe and Asia, where more government funding exists for developing these kinds of endeavors. I don’t expect many of the big gaming companies in the US to create experimental games of this nature. Although, they might in the future, after the proven economic viability of them. In that, major movie studios started funding more smaller films after they saw successful crossover of films of the Merchant Ivory variety. Although, Rockstar (the maker of Grand Theft Auto) have the upcoming and already controversial game Bully, where you must navigate a boarding school as a new student. It was described by the New York TImes as having, “an open world for the players to explore, tightly defined and memorable characters, a strong story line, [and] high-end voice acting,” which is precisely what Adams call for in his article.

Regardless of who moves video games and its coverage further, it’s bound to happen. Although, these new forms may not look exactly has Adams and Klosterman describe or wish. Media takes time to evolve, just compare the “highbrow” television series the HBO produces as compared to rather “lowbrow” television from the 50s. (I will admit that I don’t prefer one over the other.) For a great example of how a medium transforms the perspective of an artist, see Scott McCloud’s description of the movement from comic book fan to student to professional to genre pushing pioneer in Understanding Comics. If someone really wants to write video game criticism in the style of Lester Bangs, then the current low barriers of entry to electronic self-publishing allows her to do so. Creating video games, of course, requires a lot more resources. However, in closing, Adams states, “maybe I’ll design one myself, just for the fun of it.”

call for papers: what to do with a million books

The Humanities Division at the University of Chicago and the College of Science and Letters at the Illinois Institute of Technology are hosting an intriguing colloquium on the future of research in the humanities in response to the rapid growth of digital archives. They are currently accepting paper proposals, which are due at the end of August.

Here is the call for papers:

What to Do with a Million Books: Chicago Colloquium on Digital Humanities and Computer Science

Sponsored by the Humanities Division at the University of Chicago and the College of Science and Letters at the Illinois Institute of Technology.

Chicago, November 5th & 6th, 2006

Submission Deadline: August 31st, 2006

The goal of this colloquium is to bring together researchers and scholars in the Humanities and Computer Sciences to examine the current state of Digital Humanities as a field of intellectual inquiry and to identify and explore new directions and perspectives for future research.

In the wake of recent large-scale digitization projects aimed at providing universal access to the world’s vast textual repositories, humanities scholars, librarians and computer scientists find themselves newly challenged to make such resources functional and meaningful.

As Gregory Crane recently pointed out (1), digital access to “a million books” confronts us with the need to provide viable solutions to a range of difficult problems: analog to digital conversion, machine translation, information retrieval and data mining, to name a few. Moreover, mass digitization leads not just to problems of scale: new goals can also be envisioned, for example, catalyzing the development of new computational tools for context-sensitive analysis. If we are to build systems to interrogate usefully massive text collections for meaning, we will need to draw not only on the technical expertise of computer scientists but also learn from the traditions of self-reflective, inter-disciplinary inquiry practiced by humanist scholars.

The book as the locus of much of our knowledge has long been at the center of discussions in digital humanities. But as mass digitization efforts accelerate a change in focus from a print-culture to a networked, digital-culture, it will become necessary to pay more attention to how the notion of a text itself is being re-constituted. We are increasingly able to interact with texts in novel ways, as linguistic, visual, and statistical processing provide us with new modes of reading, representation, and understanding. This shift makes evident the necessity for humanities scholars to enter into a dialogue with librarians and computer scientists to understand the new language of open standards, search queries, visualization and social networks.

Digitizing “a million books” thus poses far more than just technical challenges. Tomorrow, a million scholars will have to re-evaluate their notions of archive, textuality and materiality in the wake of these developments. How will humanities scholars, librarians and computer scientists find ways to collaborate in the “Age of Google?”

(1) http://www.dlib.org/dlib/march06/crane/03crane.html

Colloquium Website

http://dhcs.uchicago.edu/announcement/

Date

November 5th & 6th, 2006

Location

The University of Chicago

Ida Noyes Hall

1212 East 59th Street

Chicago, IL 60637

Keynote Speakers

Greg Crane (Professor of Classics, Tufts University) has been engaged since 1985 in planning and development of the Perseus Project, which he directs as the Editor-in-Chief. Besides supervising the Perseus Project as a whole, he has been primarily responsible for the development of the morphological analysis system which provides many of the links within the Perseus database.

Ben Shneiderman is Professor in the Department of Computer Science, founding Director (1983-2000) of the Human-Computer Interaction Laboratory, and Member of the Institute for Advanced Computer Studies and the Institute for Systems Research, all at the University of Maryland. He is a leading expert in human-computer interaction and information visualization and has published extensively in these and related fields.

John Unsworth is Dean of the Graduate School of Library and Information Science and Professor of English at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Prior to that, he was on the faculty at the University of Virginia where he also led the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities. He has published widely in the field of Digital Humanities and was the recipient last year of the Lyman Award for scholarship in technology and humanities.

Program Committee

Prof. Helma Dik, Department of Classics, University of Chicago

Dr. Catherine Mardikes, Bibliographer for Classics, the Ancient Near East, and General Humanities, University of Chicago

Prof. Martin Mueller, Department of English and Classics, Northwestern University

Dr. Mark Olsen, Associate Director, The ARTFL Project, University of Chicago

Prof. Shlomo Argamon, Computer Science Department, Illinois Institute of Technology

Prof. Wai Gen Yee, Computer Science Department, Illinois Institute of Technology

Call for Participation

Participation in the colloquium is open to all. We welcome submissions for:

1. Paper presentations (20 minute maximum)

2. Poster sessions

3. Software demonstrations

Suggested submission topics

* Representing text genealogies and variance

* Automatic extraction and analysis of natural language style elements

* Visualization of large corpus search results

* The materiality of the digital text

* Interpreting symbols: textual exegesis and game playing

* Mashup: APIs for integrating discrete information resources

* Intelligent Documents

* Community based tagging / folksonomies

* Massively scalable text search and summaries

* Distributed editing & annotation tools

* Polyglot Machines: Computerized translation

* Seeing not reading: visual representations of literary texts

* Schemas for scholars: field and period specific ontologies for the humanities

* Context sensitive text search

* Towards a digital hermeneutics: data mining and pattern finding

Submission Format

Please submit a (2 page maximum) abstract in either PDF or MS Word format to dhcs-submissions@listhost.uchicago.edu.

Important Dates

Deadline for Submissions: August 31st

Notification of Acceptance: September 15th

Full Program Announcement: September 15th

Contact Info

General Inquiries: dhcs-conference@listhost.uchicago.edu

Organizational Committee

Mark Olsen, mark@gide.uchicago.edu, Associate Director, ARTFL Project, University of Chicago.

Catherine Mardikes, mardikes@uchicago.edu, Bibliographer for Classics, the Ancient Near East, and General Humanities, University of Chicago.

Arno Bosse, abosse@uchicago.edu, Director of Technology, Humanities Division, University of Chicago.

Shlomo Argamon, argamon@iit.edu, Department of Computer Science, Illinois Institute of Technology.

kairos turns ten

Last week marked the release of the ten year anniversary issue of Kairos, the online refereed journal of rhetoric, technology and pedagogy. The anniversary issue looks both back and forward. This milestone is notable because ten web years feels like dog years. Just consider the state of the web in 1996, where amazon.com was one year old, altavista was the leading search engine, Flash 1 got its release, and javascript was the cutting edge in web programming. Started by graduate students, Kairos has always focused on webtexts which explored the new potentials of the web as a medium, rather than simply uploading the static text of a print journal.

The issue contains interviews with people reflecting upon their experiences with rhetoric/ composition and digital technology and Kairos. As well, Jim Kalmbach gives a good overview of the scholarship which took place within Kairos over the past ten years. He concludes with this following statement:

“…we do not need ever more stunning hypermediated essays; we need new forms of scholarship; we need to think about new ways of using digital writing spaces to make meaning.”

His statement is a good transition to a new section in Kairos called Inventio, which will publicly track an article through the editorial process from inception to publication. As described, this section will:

(a) to provide a publication venue for experimental scholarly texts that push technological boundaries, and (b) to make Kairos’ editorial and peer-review decisions for innovative scholarly webtexts more explicit.

I’m looking forward to seeing the first article from this section to appear in the fall of next year. It is another project along the same lines as our project, MediaCommons. People from many directions are clearly realizing the potential in pursuing more ways to develop and share academic scholarship. I excited to see that it is starting to occur on many fronts, and I am happy that the institute, as well as, this pioneering journal are part of it.

shifting forms of graffiti

A few weekends ago, I was returning into Manhattan from upstate New York. Coming down the FRD along the East River, we past Keith Haring’s “Crack is Wack” mural on 128th and 2nd. I remember the first time I saw it in the 80s on a family day trip into the city. The work is strikes me as quite extraordinary, even 20 years after its creation in 1986. By that time, Haring was established in the art world, having already shown at the Venice Biennale and the Whitney Biennial and had solo shows at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery and the Leo Castelli Gallery. Even though Haring was part of that contemporary/ high brow art world, he still maintained a connection to his roots of skirting the lines between public street art and illegal graffiti. “Crack is Wack” mixed of graffiti street culture, political and social messages, and high art. Although, the mural was quickly placed under the protection and jurisdiction of the City Department of Parks.

Haring took cues from graffiti, among other sources of influence, and created his own style and form. Revisiting “Crack is Wack” got me thinking about graffiti and how it has evolved of the past few decades. The funny thing about living in New York is that, after a while, you start seeing through the visual chaos of our surroundings. When you take a moment to stop and look, it is amazing what you can actually see. The things that you walk by everyday, especially stand out.

Graffiti, which had faded into the background visual noise of New York, was back on my radar screen. It was, of course, everywhere, but it had also changed since I really paid attention to it. Ben posted about a show on graffiti at the Brooklyn Museum, and that was just one aspect of how graffiti has expanded beyond the traditional notions of the form. At the institute, we spend a lot of time thinking about the evolution of media, and it seems that graffiti is no different.

On a side street near Little Italy, there used to be an advertisement for the Sony PSP done by the graffiti artists Tat’s Cru. Now, the brick space has a place holder of an advertisement for these graffiti artists for hire. An interesting comment was left by a rival tagger, saying “sell out.” And then someone else left their tag over the unsolicited commentary. I love the on-going asynchronous dialogue occurring on this brick wall of this corner deli. It is not surprising that others would be upset at Tat’s Cru getting paid by advertisers for marketing. The website shows a piece that they did for BP. Working for the oil industry certainly will raise doubts to the authenticity and street credibility by purists of the form.

On a side street near Little Italy, there used to be an advertisement for the Sony PSP done by the graffiti artists Tat’s Cru. Now, the brick space has a place holder of an advertisement for these graffiti artists for hire. An interesting comment was left by a rival tagger, saying “sell out.” And then someone else left their tag over the unsolicited commentary. I love the on-going asynchronous dialogue occurring on this brick wall of this corner deli. It is not surprising that others would be upset at Tat’s Cru getting paid by advertisers for marketing. The website shows a piece that they did for BP. Working for the oil industry certainly will raise doubts to the authenticity and street credibility by purists of the form.

Perhaps, the work of the Tats Cru has not branched off to the new genre of graffiti but circled back to another form. Take this painted billboard for the debut solo record by Radiohead frontman Thom Yorke. The billboard appeared in Williamsburg in the weeks leading up to its release. Within moments, my initial thought that it was some hard core fan’s ode to British rock was replaced with the realization that this was paid for by a record label.

Referencing graffiti in advertising is nothing new. Turning actual graffiti into the advertising was the obvious next step. If graffiti is paid for and created for marketing purposes, at what point does it stop being graffiti? Has it turned into something else? Is it just a style of art using spray paint to create forms referencing hip-hop?

Sometime after seeing Haring work, I passed this stoop a few blocks north of Chinatown. There was another similar work by the same artist I saw in the Lower East Side, however, I couldn’t find it again.

Sometime after seeing Haring work, I passed this stoop a few blocks north of Chinatown. There was another similar work by the same artist I saw in the Lower East Side, however, I couldn’t find it again.

But the work kept on reappearing. And then, I noticed another one a few blocks from the institute’s office in Brooklyn. I probably walked past it hundreds of times before stopping to notice it. You can see where someone tried to tear it off, because in fact, the figures are not drawn on the wall, but on paper. The image is then transferred to the wall. Is this cheating? Suddenly, form and material are being challenged.

I did stumble upon Ping Magazine, when a friend sent me another article from the site. I finally learned that these pieces were created by an artist who goes by Swoon. She gave an interview for the New York Times, and describes herself as street artist, but considers her work graffiti. More importantly, she does not talk about the legal nature or the materiality of her work, but focuses on its location in public spaces and its direction interaction with people.

Keith Haring ended up being a great starting point, because of his work is a hybrid many forms and influences, including graffiti but also things beyond it. His mural reminded me that graffiti has embodied a range of politics, material and cultures for decades. Forms of expression emerge, branch off and circle back. Subsequent generations focus on different areas, be it monetary or expressive. Today, art and advertising are often re-appropriations of each other, as forms blend into one another. Empty spaces are filled with media by both artists and advertisers. The arts organization the Wooster Collective shows how broadly the concept of street art can extended. Trying to restrict these forms to bounded definitions is marginally useful, and often futile.

In this investigation, I was surprised at what I found, and amused at how often I circled back to the question of what is graffiti? The question or process of re-seeing something itself is not that surprising, particularly in the context of our work at the institute. Although, we focus more time on textual media, many of the questions remain the same. As we witness the evolving forms of text and the book, we can learn from other forms that turn into something slightly familiar but also remarkably new.

google on mars

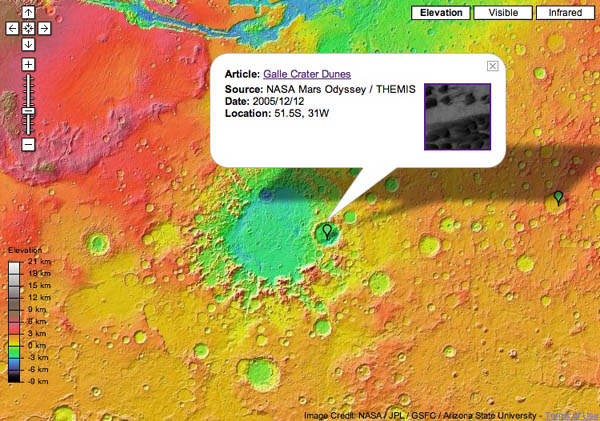

Apparently, this came out in March, but I ‘ve only just stumbled on it now. Google has a version of its maps program for the planet Mars, or at least the part of if explored and documented by the 2001 NASA Mars Odyssey mission. It’s quite spectacular, especially the psychedelic elevation view:

There’s also various info tied to specific coordinates on the map: location of dunes, craters, planes etc., as well as stories from the Odyssey mission, mostly descriptions of the Martian landscape. It would be fun to do an anthology of Mars-located science fiction with the table of contents mapped, or an edition of Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles. Though I suppose there’d a fair bit of retrofitting of the atlas to tales written out of pure fancy and not much knowledge of Martian geography (Marsography?). If nothing else, there’s the seeds of a great textbook here. Does the Google Maps API extend to Mars, or is it just an earth thing?

can advertising liberate textbooks?

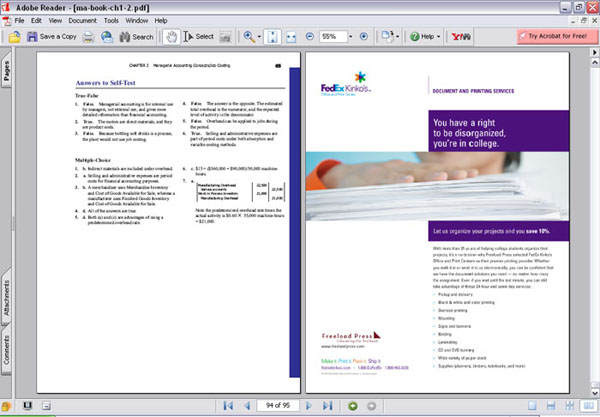

The aptly named Freeload Press is giving away free PDFs (free as in free beer, or free market) of over 100 textbooks titles (mostly in business and finance, though more is planned). All students have to do is fill out an online survey and then the download is theirs, to use on a computer or to print out. Where does the money come from? Ads. Ads in the pages of the textbooks.

An ad for FedEx Kinkos in a sample Freeload textbook. Hmmm, wonder where I should get this thing printed?

Ads in textbooks is undoubtedly a depressing thought. Even more depressing, though, is the outlandish cost of textbooks, and the devious, often unethical, ways that textbook publishers seek to thwart the used book market. This Washington Post story gives a quick overview of the problem, and profiles the St. Paul, Minnesota-based Freeload.

Though making textbooks free to students is an admirable aim, simply shifting the cost to advertisers is not a good long-term solution, further eroding as it does the already much-diminished borderline between business and education (I suppose, though, that ads in business ed. textbooks in some ways enact the underlying precepts being taught). There are far better ideas out there for, as Freeload promises, “liberating the textbook” (a slogan that conjures the Cheney-esque: the textbooks will greet us as liberators).

One of them comes from Adrian Lopez Denis, a PhD candidate in Latin American history at UCLA. I’m reproducing a substantial chunk of a brilliant comment he posted last month to the Chronicle of Higher Ed’s Wired Campus blog in response to their coverage of our announcement of MediaCommons. We just met with Adrian while in Los Angeles and will likely be collaborating with him on a project based on the ideas below. Basically, his point is that teachers and students should collaborate on the production of textbooks.

Students are expected to produce a certain amount of pages that educators are supposed to read and grade. There is a great deal of redundancy and waste involved in this practice. Usually several students answer the same questions or write separately on the same topic, and the valuable time of the professionals that read these essays is wasted on a rather repetitive task.

[…]

As long as essay writing remains purely an academic exercise, or an evaluation tool, students would be learning a deep lesson in intellectual futility along with whatever other information the course itself is trying to convey. Assuming that each student is writing 10 pages for a given class, and each class has an average of 50 students, every course is in fact generating 500 pages of written material that would eventually find its way to the campus trashcans. In the meantime, the price of college textbooks is raising four times faster that the general inflation rate.

The solution to this conundrum is rather simple. Small teams of students should be the main producers of course material and every class should operate as a workshop for the collective assemblage of copyright-free instructional tools. Because each team would be working on a different problem, single copies of library materials placed on reserve could become the main source of raw information. Each assignment would generate a handful of multimedia modular units that could be used as building blocks to assemble larger teaching resources. Under this principle, each cohort of students would inherit some course material from their predecessors and contribute to it by adding new units or perfecting what is already there. Courses could evolve, expand, or even branch out. Although centered on the modular production of textbooks and anthologies, this concept could be extended to the creation of syllabi, handouts, slideshows, quizzes, webcasts, and much more. Educators would be involved in helping students to improve their writing rather than simply using the essays to gauge their individual performance. Students would be encouraged to collaborate rather than to compete, and could learn valuable lessons regarding the real nature and ultimate purpose of academic writing and scholarly research.

Online collaboration and electronic publishing of course materials would multiply the potential impact of this approach.

What’s really needed is for textbooks to liberated from textbook publishers. Let schools produce their own knowledge, and spread the wealth.

encouraging

The following was posted on Sunday by Mitch Stephens on Without Gods (for those of you still unfamiliar with it, Without Gods is the public work diary for Mitch’s forthcoming history of atheism, which we’ve been hosting for the past eight months — wow, has it been that long?!).

The following was posted on Sunday by Mitch Stephens on Without Gods (for those of you still unfamiliar with it, Without Gods is the public work diary for Mitch’s forthcoming history of atheism, which we’ve been hosting for the past eight months — wow, has it been that long?!).

Thanks

The quality of the comments here lately has seemed, to me, extraordinarily high.

One of the purposes of blogging a book as it is being written is to have ideas tested and, possibly, sharpened, transformed or overturned. This has repeatedly occurred — although I have not often weighed in with comments of my own acknowledging that. Please take this as a blanket acknowledgement and expression of appreciation.

GAM3R 7H30RY may be flashier, and more technically ambitious, but in many ways Without Gods has been a more revelatory experiment in networked writing. As Mitch acknowledges, the sustained activity, and quality, of the comment streams has been impressive, and above all, interesting to read. It’s fascinating to follow this evolving collaboration between author and reader, and to watch Mitch come into his own as a skilled moderator of blog-based discussion. It remains to be seen how these conversations will end up shaping the finished book, but for some examples of a tangible collaboration taking place, take a look at these recent “Author Needs Advice” posts (part 1, part 2), in which Mitch asks for feedback on specific sections of the work-in-progress. Whatever the outcome, it’s clear that this reconfiguration of the writing process is yielding real rewards.

notable wikipedians

Simon Pulsifer: “the king of Wikipedia”

“He lives at home and doesn’t have a girlfriend.”

(photo: Bill Grimshaw/The Globe and Mail)

I just came across this story in The Toronto Globe and Mail about a young man from Ottawa by the name of Simon Pulsifer who, under the moniker SimonP, is Wikipedia’s most prolific contributor: “with 78,000 entries edited and 2,000 to 3,000 new articles to his name. He can’t remember the exact number.”

Pulsifer is also the subject of an article in Wikipedia, which, like many of the vanity stubs devoted to the encyclopedia’s editors, was nominated for deletion, only to be voted a keeper after some discussion. Justin Hall, a colleague of ours at USC, often cited as the first blogger, and a distinguished Wikipedian in his own right, offered the following in defense of the Pulsifer page:

As Wikipedia grows in importance and global reach, the most passionate participants in this collective editing experiment become important global intellectuals. Simon Pulsifer is one of the first public Wikipedians – with a great number of articles, a passion for editing under-developed subjects, and a strong sense of the mission of Wikipedia. He might not care to have an article about him here, but already mainstream media outlets (a Canadian newspaper) and online news sites (digg.com) have saluted his work. That attention and importance is only likely to increase. Let’s keep this article because Simon Pulsifer has already reached a greater number of people than many of the “historic” individuals described on Wikipedia.

Both Pulsifer and Hall are members of what could be considered the Wikipedia elite, the “notable Wikipedians“. Many of these probably deserve a good share of the credit for Wikipedia’s success. Now, though, I’m more interested in how Wikipedia’s corps of editors might gradually expand to include a greater slice of the public: teacher, students, and people from all walks of life.

Zealous Wikipedia hobbyists like Pulsifer, god love ’em, will hopefully, over time, be considered the exceptions that prove the general rule of participation: editing as a more modest pursuit that one builds into one’s intellectual life and lifelong learning regimen. If enough people begin to take part in this way, Wikipedia could become more diverse, more exhaustive, and more accurate than it already is. The Pulsifers and Halls might end up being its governors, its civil servants, its politicians. Of course, it is the process that is most important: the kind of civic participation and engagement over points of dissent that collaborating on Wikipedia entails. Bob explained this eloquently last week. Or, as Pulsifer describes it:

You write an article and you think you’ve made it as good as it can be and then you put it out there for everyone to see and edit. And within just a few minutes, you have started a dialogue over how best to represent a subject.

pinkwater dips his toes (and quill) into the web

The Institute is back in Los Angeles at USC, our home away from home in academe, where, for the next two days, we’re holding an introductory “boot camp” session with a small group of professors who will begin using Sophie in their classes this fall. USC is just southwest of downtown LA, right near the La Brea Tar Pits, which, incidentally, is the starting point of the latest book by one of my favorite childhood writers, Daniel Manus Pinkwater, who, I just read in Publishers Weekly, is publishing his newest book online.

Pinkwater, author of Lizard Music, The Hoboken Chicken Emergency, the Snarkout Boys novels, and many, many others, is publishing his newest effort, The Neddiad, “a rip-roaring, foot-stomping, blood-curdling adventure, with station stops in Chicago, Flagstaff, and Hollywood, California,” free on his website as a serial.

With the blessing of his publisher, Houghton Mifflin, Pinkwater has set up a simple, very readable little site, where readers can imbibe the book, in slightly raw form, one chapter per week.

What we are presenting is the original author’s manuscript. There are some typos, and editorial corrections, and changes by me are not included. So the published book will be slightly different. I am a careful writer, and worked with a fine editor, so the differences are not great, but I thought it might be of interest for some to see what the book was like when handed in.

In many ways, this is a very PInkwater move — plugging his book into an electrical socket and watching it glow. There’s also a discussion forum, so it’s something of a networked book:

Readers are welcome to post comments, criticisms, complaints, and exchange remarks–a link will be provided, and I may periodically chime in to discuss and argue with the posters.

Pinkwater told PW:

When I was younger a circus hand showed me how they let kids sneak into the circus. If they were bold enough to try, they got to stay. I’m trying to keep that feeling for kids with this project. It lets kids sneak into the tent. We’re deliberately keeping it from looking slick; there are no ads. Of course, it’s with Houghton Mifflin’s kind permission that we can offer this, but it’s still a bit of homebrew, slightly different from the finished version. We hope that the readers who enjoy what they find online will want to buy the book, too.

If nothing else, Pinkwater has grasped an important (and counterintuitive) principle of web publishing: that giving stuff away can help sell books. It helps facilitate a discussion about that stuff, and can make readers feel better disposed toward you and your work (i.e. more likely to buy it in print). One chapter per week is a rather dribbling pace, however (recall the somewhat disingenuous serialization of Pulse by FSG), and might be a bit like Chinese water torture for Pinkwater’s ardent fans. But we’ll see.