One of the most interesting things about new media is the light that it shines on how old media works and doesn’t work, a phenomenon that Marshall McLuhan encapsulated precisely with his declaration that a fish doesn’t realize that it lives in water until it finds itself stranded on land. The latest demonstration: an article on the front page of yesterday’s New York Times. (The version in the International Herald Tribune might be more rot-resistant, though it lacks illustrations.) The Times details, with no small amount of snark, how the conservatives have taken it upon themselves to construct an Encyclopedia of American Conservatism.

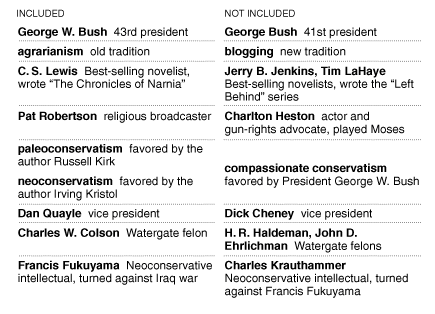

We’ve spent a disproportionate amount of time discussing encyclopedias on this blog. What’s interesting to me about this one is how resolutely old-fashioned it is: it’s print-based through and through. The editors have decided who’s in and who’s out, as the Times points out in this useful chart:

Readers are not allowed to argue with the selections: American Conservatism is what the editors say it is. It’s a closed text and not up for discussion. Readers can discuss it, of course – that’s what I’m doing here – but such discussions have no direct impact on the text itself.

There’s a political moral to be teased out here – conservative thinking is dogmatic rather than dialectical – but that’s too easy. I’m more interested in how we think about this. Would we notice the authoritarian nature of this work if we didn’t have things like the Wikipedia to compare it to? Someone who knows more about book history than I can confirm whether Diderot & d’Alembert had to deal with readers disgruntled by omissions from their Encyclopédie. It’s only now, however, that we sense the loss of potential: compared to the Wikipedia this seems limiting.

This specific example makes me wonder how ‘new media’ has affected the overall political landscape of the country/world. Certainly it seems that in recent years we have, as a society, become more and more polarized politically with the center losing ground to the extremes.

Could this change be related to the relatively recent advent of participatory media? Has the fact of online communities that have sprung up actually contributed to the polarization of society by removing the geographical boundaries on social activities and allowing you to interact solely with people who share your views even if no on in your area does? Or perhaps things haven’t really changed at all, just our perception of things because it’s those at the extremes who are more willing to devote their time towards actual participation in the public discussion fueled by new media.

Obviously the technology of information delivery has the capacity to change culture: radio, tv, and the world wide web have all clearly illustrated that. The latest evolution of media will certainly do so as well, but how? And how much influence/responsibility do we have in guiding that change?

Apparently, the Encyclopedia of American Conservatism has been in the works since 1990, and was initially conceived as a counterweight to the Encyclopedia of the American Left. Obviously, the communications landscape has changed significantly since then, but I don’t think the new/old media distinction necessarily falls along political lines. The liberal encyclopedia is likely every bit as dogmatic and impermeable as the conservative.

Perhaps the more interesting question concerns the difference between the production of so-called general knowledge and the production of ideology. Wikipedia is intended as a general knowledge resource, one that is as neutral and ideologically disentangled as is humanly possible. The Encyclopedia of American Conservatism, on the other hand, is aimed at encapsulating a pure strain of an ideology. It is a canonizer, a guide to orthodoxy. I wonder whether something like this can be produced by collective, dialogic means, or if it must needs be the work of an elite — the keepers of the flame. Of course, Wikipedia and open-source software and all these groovy collectivist things contain their embedded ideologies, but they are purposed as public works. Is the difference then that collectives produce ideology unwittingly while elites produce it knowingly? Or is the real revolution when serious, intelligent opinions can be worked out and expressed collaboratively?