The term “political art” has implications that might well deter people from viewing it, especially here where the political is regarded as unaesthetic. It is sad that when an American artist makes “political art” it becomes news. This has been the case with the presence of political films in Cannes, as chronicled by A. O. Scott in the New York Times. He makes a parallel with the 60’s as a golden age of filmmaking, and in particular the 1968 Cannes Film Festival, where the artistic and the political were absolutely interconnected. To say that the problems we are facing today are less significant than those of the 60’s is to exchange lack of hope for the authentic belief in change that permeated that era.

The big difference today is that communications are immediate and indispensable, but that their ubiquity has also numbed us. War and catastrophe as spectacle have always fed the public imagination, but today fiction and fact, reality and artifice, have collapsed into yet another consumer product. On the other hand, the availability of affordable technology has made photography, video and filmmaking accessible to many. Now, it is possible to see interesting and good quality pieces from places far away from the established centers of film production. Cannes is still the favorite showplace of international cinema, but it doesn’t mean that many movies that make it there ever go beyond the art houses. So, the presence of Al Gore’s “An Inconvenient Truth,” Richard Linklater and Eric Schlosser’s “Fast Food Nation” or Linklater’s “A Scanner Darkly” and Richard Kelly’s “Southland Tales” are news not because they are represented in Cannes but because they tell stories based on present circumstances without fear of being “political.”

Holland Cotter the art critic of The New York Times reviews some current exhibitions that make political commentary noting that in 21st-century America political art is not “protest art” but a mirror. But, what else is art, past and present, than a mirror that uncannily shows political realities? The fact that many artists insist on looking at their belly buttons instead of at the world, is in itself a political commentary of the times. Cotter reviews Harrell Fletcher’s http://www.harrellfletcher.com/# show at White Columns, images from a museum in Ho Chi Minh City, as a horrific document of the Vietnam War. Jenny Holzer at Cheim and Read shows a series of silk screens of declassified documents related to Abu Ghraib, which are faithful to each official word with the exception of their magnification, thus becoming a commentary on our nation’s violence.

from Archive — Jenny Holzer

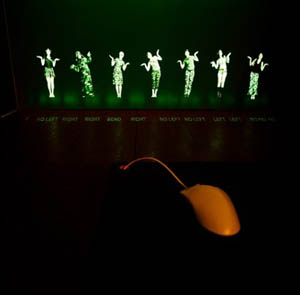

Coco Fusco‘s video, “Operation Atropos,” documenting the training on interrogation and resistance program she and six women went through in the woods of the Poconos, offers a political glance at the methods of physical and mental persuasion. Apart from the obviously political, the viewer realizes that this program, run by former members of the CIA, has been conceived for the private sector.

Operation Atropos

Cotter concludes his article asking, “So what kind of political art is this? It isn’t moralizing or accusatory. It’s art for a time when play-acting and politics seem to be all but indistinguishable.” They are.

It is always enormously refreshing to visit the art galleries, and to be reminded that many artists in many places, perhaps because they are faced with stark realities on a daily basis, have indeed a lot to comment. The Asian Contemporary Art Week (5/22-5/27) was one of those occasions (and still is since many galleries will continue displaying Asian art for a few more weeks.) Shilpa Gupta‘s interactive video environments at Bose Pacia offer a comment on power, militarism and imperialism. In one of the pieces the viewer sees a bucolic landscape in Kashmir and as s/he touches the screen military guards appear. Truth is indeed a fragile and many times deceiving construction.

Untitled, 2005 — Shilpa Gupta

Tejal Shah‘s video installation at Thomas Erben presents the transgender community in India from within, a reality that is equally painful and celebratory. At the Sculpture Center, as part of the Grey Flags exhibition, there is a film by Apichatpong Weerasethakul the Thai filmmaker whose fresh approach to reality has taken him to use non-professional actors and improvised dialogue, offering a sober and supetcharged vision of reality in Thailand. Tilton Gallery brings together 34 contemporary Chinese artists entitled “Jiang Hu” whose literal meaning is “rivers and lakes” but that metaphorically means a place removed from the mainstream. In medieval literature it means a realm inhabited by outsiders, monks, fortune-tellers and artists who had magical powers. In the context of this exhibit that shows an interesting and disparate group, “Jiang Hu” evokes a complex reality: China an outsider within the global world.

if:book

A Project of the Institute for the Future of the Book