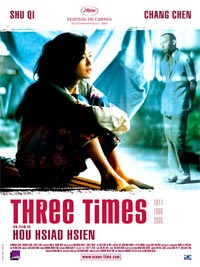

This past weekend, I saw a remarkable film: “Three Times,” by Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien. It’s a triptych on love set in Taiwan in three separate periods — 1966, 1911, and 2005 — each section focusing on a young man and woman, played by the same actors. Hou does incredible things with time. Each of the episodes, in fact, is a sort of study in time, not just of a specific time in history, but in the way time moves in love relationships. The opening shots of the first episode, “A Time for Love,” announce that things will be operating in a different temporal register. Billiard balls glide across a table. You don’t yet understand the rules of the game that is being played. Characters gradually emerge and the story unfolds through strange compressions and contractions of time that comprise a weird logic of yearning.

This past weekend, I saw a remarkable film: “Three Times,” by Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien. It’s a triptych on love set in Taiwan in three separate periods — 1966, 1911, and 2005 — each section focusing on a young man and woman, played by the same actors. Hou does incredible things with time. Each of the episodes, in fact, is a sort of study in time, not just of a specific time in history, but in the way time moves in love relationships. The opening shots of the first episode, “A Time for Love,” announce that things will be operating in a different temporal register. Billiard balls glide across a table. You don’t yet understand the rules of the game that is being played. Characters gradually emerge and the story unfolds through strange compressions and contractions of time that comprise a weird logic of yearning.

This is the first of Hou’s films that I’ve seen (it’s only the second to secure an American release). I was reminded of Tarkovsky in the way Hou uses cinema to convey the movement of time, both across the eras and within individual episodes. There’s much to say about this film, and I hope to see it again to better figure out how it does what it does. The reason I bring it up here is that the third story — “A Time for Youth,” set in contemporary Taipei — contains some of the most profound and visually arresting depictions of the mediation of intimate relationships through technology that I’ve ever seen. Cell-phones and computers have been popping up in movies for some time now, usually for the purposes of exposition or for some spooky haunted technology effect, like in “The Matrix” or “The Ring.” In “Three Times,” these new modes of contact are probed more deeply.

The story involves a meeting of an epileptic lounge punk singer and an admiring photographer, while the singer’s jilted female lover lurks in the margins.  Hou weaves back and worth between intense face-to-face meetings and asynchronous electronic communication. At various times, the screen of the movie theater (the IFC in Greenwich Village) is completely filled with an extreme close-up of a cell-phone screen or a computer monitor, the text of an SMS or email message as big as billboard lettering. The pixelated Chinese characters are enormous and seem to quiver, or to be on the verge of melting. A cursor blinking at the end of an alleged suicide note typed into a computer is a dangling question of life and death, or perhaps just a sulky dramatic gesture.

Hou weaves back and worth between intense face-to-face meetings and asynchronous electronic communication. At various times, the screen of the movie theater (the IFC in Greenwich Village) is completely filled with an extreme close-up of a cell-phone screen or a computer monitor, the text of an SMS or email message as big as billboard lettering. The pixelated Chinese characters are enormous and seem to quiver, or to be on the verge of melting. A cursor blinking at the end of an alleged suicide note typed into a computer is a dangling question of life and death, or perhaps just a sulky dramatic gesture.

What’s especially interesting is that the most expressive speech in “A Time for Youth” is delivered electronically. Face-to-face meetings are more muted and indirect. There’s an eerie episode in a nightclub where the singer is performing on stage while the photographer and another man circle her with cameras, moving as close as they can without actually touching her, shooting photos point blank.

But it was the use of screens that really struck me. By filling our entire field of vision with them — you almost feel like you’re swimming in pixels — Hou conveys how tiny channels of mediated speech can carry intense, all-consuming feeling. The weird splotchiness of digital text at close range speaks of great vulnerability. Similarly, the revelation of the singer’s epilepsy is not through direct disclosure, but happens by accident when she leaves behind a card with instructions for what to do in case of a seizure, after spending the night at the photographer’s apartment. This all strikingly follows up the previous episode, “A Time for Freedom,” which is done as a silent film with all the dialogue conveyed on placards.

It’s one of those things that suddenly you viscerally understand when a great artist shows you: how these technologies spin a web of time around us, sending voices and gestures across space instantly, but also placing a veil between people when they actually share a space. In many ways, these devices bring us closer, but they also fracture our attention and further insulate us. Never are you totally apart, but seldom are you totally together.

“Three Times” is currently out in a few cities across the US and rolling out progressively through June in various independent movie houses (more info here).

if:book

A Project of the Institute for the Future of the Book

New York is one of those places where one can fall in love with a filmmaker who has not had many American releases. I have been fortunate enough to see Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s “Café Lumiè re”(2003), “Millennium Mambo” (2001) and “Flowers of Shanghai” (1998) in different independent venues.

Of course, I ran to see “Three Times” (2005) and confirmed my total addiction to his movies. The leitmotif of this cinematic tour de force is precisely that intimate communication has always been mediated, if not hampered, by society and its devices. In “A Time for Love,” the rituals of Taiwanese society in the 60’s veil any possibility of direct communication. So the boy writes formally identical letters to different girls, following traditional epistolary form. Here, music (The Platters’ “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” and Aphrodite’s “Rain and Tears”) mediates love and when communication finally occurs, it is manifested non-verbally. In “A Time for Freedom,” set during the uprising against the Qing Dynasty in mainland and the Japanese occupation of Taiwan, freedom is a double referential. Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s masterful use of silent movie emphasizes the artifice in a highly ritualized society where every word is carefully veiled the same way courtesans are wrapped in layers of gorgeous silk brocade. In “A Time for Youth,” every inch of physical and aural space is artificially filled, but life is eerily devoid of meaning. Communication becomes part of the urban landscape: superficial, instant, but ultimately insufficient.

Sol,

This is a beautiful encapsulation of the film. I’m definitely going to see it again!

And you’re so right that the hi-tech mediation of “A Time for Youth” is just the latest iteration in a long history of veiled communication. Hou’s empathy spans a century.