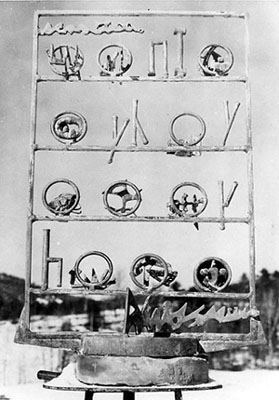

Last weekend, I found myself in the familiar position of racing to catch a long-running art show before it closed. This time it was the David Smith retrospective at the Guggengheim. (The show ends on May 14th.) The collection includes sculptural nods to Abstract Expressionism and Surrealism, as well as, foreshadowing Minimalism. Once an ironmonger, Smith employs found objects, he molds and welds into sculpture influenced as much by painting as the traditions of sculpture. While I generally prefer his larger scale pieces he produced late in his career, I was struck by a fascinating mid-career piece entitled, “The Letter” (1950).

The sculpture is a representation of a letter, that begins with a salutation in the upper right hand corner and closes with a signature. A range of theories abound to its meaning. Are the glyphs letters, words, human figures, or scenes? Is this a letter to his wife? One art historian suggests the text references a line from Wonderful Town and about leaving the state Ohio, where Smith spent part of this youth.

Or could it be a response to an author’s writing? The audio tour offered interpretations of a hint to the work of James Joyce that Smith gave in an interview. Listening to these following quotes from Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (0:40 – 1:16 of the audio fiie) while looking at the piece, I see and hear relevance to our work at the institute.

“ruled barriers, along which the traced words run, march, halt, walk, stumble”

and

“lines of litters slittering up and louds of ladders slettering down”

Whether it is our overarching discussion of the shift of print text to the computer screen or an overheard criticism of the latest sacrilegious film adaptation of a beloved book, the evolution of text beyond the printed page is clearly a dynamic process. We are aided when any creative mind can demonstrate these emerging relationships in a meaningful way.

In “the Letter,” Smith coyly reveals partial hints to the artist’s intentions, freeing the viewer to create her own insights. Smith is able to simultaneously display a multitude of reflections of meaning, with each suggestion containing a seemingly direct message to the viewer (as seen by the wide ranging interpretations.) Although the iconography could and does represent letters, words and bodies, I remain continuously enamored with the Joycian interpretation.

In that, Smith transforms a book into a sculpture. “The Letter” is bounded like a book, but within those boundaries, the gestures of abstracted forms (rather than letters), the use of open space, and the three dimensionality of the work surpasses that which it mimics. Further, the abstracted sculptural forms with their multiple readings comment upon the various meanings we take from words, which are also open to multiple readings. Therefore, Smith’s vision leaves us with a physical object that embodies not just the words, themes, and emotions of the book (that is the content), but also comments on the limitations of the book as an object (or vessel which holds the content).

Smith’s work, now 56 years old, seemingly poses to us two challenges. First, when we translate print text into the digital or create born-digital books, “the Letter” reminds us that in deciding to keep or reject aspects of both the content and the vessel of the traditional book, we must be conscious of the choices we make in that process. What are we willing to sacrifice in order to achieve something greater? Second, it asks us to look at these new forms with eyes unfettered by past conventions and to focus on, appreciate, and take advantage of the potentials of the new medium.

Wow. I could look at this a long time.

Roger, if you have not already, I suggest you listen to the section of the audio clip I noted in the post. Hearing Joyce’s words while looking at “the Letter” brings out another level of meaning.

reminds me of Revs welded tags you see around