Knight Ridder, America’s second largest newspaper company, operator of 32 dailies, has been purchased by McClatchy Co., a smaller newspaper company (reported here in the San Jose Mercury News, one of the papers McClatchy has acquired). Several months ago, Knight Ridder’s controlling shareholders, nervous about declining circulation and the increasing dominance of internet news, insisted that the company put itself up for auction. After being sniffed over and ultimately dropped by Gannett Co., the country’s largest print news conglomerate, the smaller McClatchy came through with KR’s sole bid.

Knight Ridder, America’s second largest newspaper company, operator of 32 dailies, has been purchased by McClatchy Co., a smaller newspaper company (reported here in the San Jose Mercury News, one of the papers McClatchy has acquired). Several months ago, Knight Ridder’s controlling shareholders, nervous about declining circulation and the increasing dominance of internet news, insisted that the company put itself up for auction. After being sniffed over and ultimately dropped by Gannett Co., the country’s largest print news conglomerate, the smaller McClatchy came through with KR’s sole bid.

McClatchy’s chief exec calls it: “a vote of confidence in the newspaper industry.” Or is it — to riff on the cultural environmentalism metaphor — like buying beach front property on the Aral Sea?

For a more hopeful view on the future of news, Jay Rosen (who has not yet commented on the Knight Ridder sale) has an amazing post today on Press Think about online newspapers as “seeders of clouds” and “public squares.” Very much worth a read.

Monthly Archives: March 2006

cultural environmentalism symposium at stanford

Ten years ago, the web just a screaming infant in its cradle, Duke law scholar James Boyle proposed “cultural environmentalism” as an overarching metaphor, modeled on the successes of the green movement, that might raise awareness of the need for a balanced and just intellectual property regime for the information age. A decade on, I think it’s safe to say that a movement did emerge (at least on the digital front), drawing on prior efforts like the General Public License for software and giving birth to a range of public interest groups like the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Creative Commons. More recently, new threats to cultural freedom and innovation have been identified in the lobbying by internet service providers for greater control of network infrastructure. Where do we go from here? Last month, writing in the Financial Times, Boyle looked back at the genesis of his idea:

We were writing the ground rules of the information age, rules that had dramatic effects on speech, innovation, science and culture, and no one – except the affected industries – was paying attention.

My analogy was to the environmental movement which had quite brilliantly made visible the effects of social decisions on ecology, bringing democratic and scholarly scrutiny to a set of issues that until then had been handled by a few insiders with little oversight or evidence. We needed an environmentalism of the mind, a politics of the information age.

Might the idea of conservation — of water, air, forests and wild spaces — be applied to culture? To the public domain? To the millions of “orphan” works that are in copyright but out of print, or with no contactable creator? Might the internet itself be considered a kind of reserve (one that must be kept neutral) — a place where cultural wildlife are free to live, toil, fight and ride upon the backs of one another? What are the dangers and fallacies contained in this metaphor?

Ray and I have just set up shop at a fascinating two-day symposium — Cultural Environmentalism at 10 — hosted at Stanford Law School by Boyle and Lawrence Lessig where leading intellectual property thinkers have converged to celebrate Boyle’s contributions and to collectively assess the opportunities and potential pitfalls of his metaphor. Impressions and notes soon to follow.

sophie is coming!

Though we haven’t talked much about it here, the Institute is dedicated to practice in addition to the theory we regularly spout here. In July, the Institute will release Sophie, our first piece of software. Sophie is an open-source platform for creating and reading electronic books for the networked environment. It will facilitate the construction of documents that use multimedia and time in ways that are currently difficult, if not impossible, with today’s software. We spend a fair amount of time talking about what electronic books and documents should do on this blog. Hopefully, many of these ideas will be realized in Sophie.

Though we haven’t talked much about it here, the Institute is dedicated to practice in addition to the theory we regularly spout here. In July, the Institute will release Sophie, our first piece of software. Sophie is an open-source platform for creating and reading electronic books for the networked environment. It will facilitate the construction of documents that use multimedia and time in ways that are currently difficult, if not impossible, with today’s software. We spend a fair amount of time talking about what electronic books and documents should do on this blog. Hopefully, many of these ideas will be realized in Sophie.

A beta release for Sophie will be upon us before we know it, and readers of this blog will be hearing (and seeing) more about it in the future. We’re excited about what we’ve seen Sophie do so far; soon you’ll be able to see too. Until then, we can offer you this 13-page PDF that attempts to explain exactly what Sophie is, the problems that it was created to solve, and what it will do. An HTML version of this will be arriving shortly, and there will soon be a Sophie version. There’s also, should you be especially curious, a second 5-page PDF that explains Sophie’s pedigree: a quick history of some of the ideas and software that informed Sophie’s design.

truth through the layers

Pedro Meyer’s I Photograph to Remember is a work originally designed for CD ROM, that became available on the Internet 10 years later. I find it not only beautiful within the medium limitations, as Pedro says on his 2001 comment, but actually perfectly suited for both, the original CD ROM, and its current home on the internet . It is a work of love, and as such it has a purity that transcends all media.

Pedro Meyer’s I Photograph to Remember is a work originally designed for CD ROM, that became available on the Internet 10 years later. I find it not only beautiful within the medium limitations, as Pedro says on his 2001 comment, but actually perfectly suited for both, the original CD ROM, and its current home on the internet . It is a work of love, and as such it has a purity that transcends all media.

The photographs and their subject(s) have such degree of intimacy that forces the viewer to look inside and avoid all morbidity or voyeurism. The images are accompanied by Pedro Meyer’s voice. His narration, plain and to the point, is as photographic as the pictures are eloquent. The line between text and image is blurred in the most perfect b&w sense. The work evokes feelings of unconditional love, of hands held at moments of both weakness and strength, of happiness and sadness, of true friendship, which is the basis of true love. The whole experience becomes introspection, on the screen and in the mind of the viewer.

IPTR was originally a Voyager CD ROM, and it was the first ever produced with continuous sound and images, a possibility that completes, and complements, image as narration and vice-versa. The other day Bob Stein showed me IPTR on his iPod and expressed how perfectly it works on this handheld device. And, it does. IPTR is still a perfect object, and as those old photographs exist thanks to the magic of chemicals and light, this exists thanks to that “old” CD ROM technology, and will continue to exist inhabiting whatever medium necessary to preserve it.

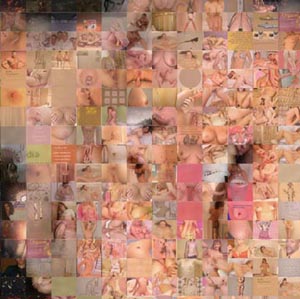

I’ve recently viewed Joan de Fontcuberta’s shows in two galleries in Manhattan; Zabriskie and Aperture,) and the connections between IPTR and these works became obsessive to me. Fontcuberta, also a photographer, has chosen the Internet, and computer technology, as the media for both projects. In “Googlegrams,” he uses the Google image search engine to randomly select images from the Internet by controlling the search engine criteria with only the input of specific key words.

I’ve recently viewed Joan de Fontcuberta’s shows in two galleries in Manhattan; Zabriskie and Aperture,) and the connections between IPTR and these works became obsessive to me. Fontcuberta, also a photographer, has chosen the Internet, and computer technology, as the media for both projects. In “Googlegrams,” he uses the Google image search engine to randomly select images from the Internet by controlling the search engine criteria with only the input of specific key words.

These Google-selected images are then electronically assembled into a larger image, usually a photo, of Fontcuberta’s choosing (for example, the image of a homeless man sleeping on the sidewalk reassembled from images of the 24 richest people in the world, Lynddie England reassembled from images of the Abu Ghraib’s abuse, or a porno picture reassembled from porno sites.). The end result is an interesting metaphor for the Internet and the relationship between electronic mass media and the creation of our collective consciousness.

For Fontcuberta, the Internet is “the supreme expression of a culture which takes it for granted that recording, classifying, interpreting, archiving and narrating in images is something inherent in a whole range of human actions, from the most private and personal to the most overt and public.” All is mediated by the myriad representations on the global information space. As Zabriskie’s Press Release says, “the thousands of images that comprise the Googlegrams, in their diminutive role as tiles in a mosaic, become a visual representation of the anonymous discourse of the internet.”

Aperture is showing Fontcuberta’s “Landscapes Without Memory” where the artist uses computer software that renders three-dimensional images of landscapes based on information scanned from two-dimensional sources (usually satellite surveys or cartographic data.) In “Landscapes of Landscapes” Fontcuberta feeds the software fragments of pictures by Turner, Cézanne, Dalí, Stieglitz, and others, forcing the program to interpret this landscapes as “real.”

Aperture is showing Fontcuberta’s “Landscapes Without Memory” where the artist uses computer software that renders three-dimensional images of landscapes based on information scanned from two-dimensional sources (usually satellite surveys or cartographic data.) In “Landscapes of Landscapes” Fontcuberta feeds the software fragments of pictures by Turner, Cézanne, Dalí, Stieglitz, and others, forcing the program to interpret this landscapes as “real.”

These painted and photographic landscapes are transformed into three-dimensional mountains, rivers, valleys, and clouds. The result is new, completely artificial realities produced by the software’s interpretation of realities that have been already interpreted by the painters. In the “Bodyscapes” series, Fontcuberta uses the same software to reinterpret photographs of fragments of his own body, resulting in virtual landscapes of a new world. By fooling the computer Fontcuberta challenges the limits between art, science and illusion.

Both Pedro Meyer and Joan de Fontcuberta’s use of photography, technology and the Internet, present us with mediated worlds that move us to rethink the vocabulary of art and representation which are constantly enriched by the means by which they are delivered.

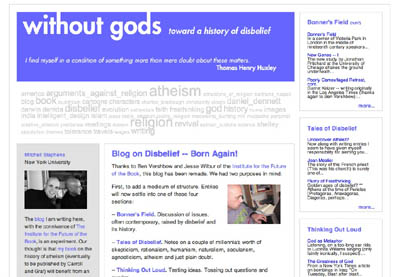

without gods: born again!

Unrest in the Middle East. Cartoons circulated and Danish flags set ablaze (who knew there were so many Danish flags?) A high-profile debate in the pages of the New York Times between a prominent atheist and a Judeo-Christian humanist. Another setback for the “intelligent design” folks, this time in Utah. Things have been busy of late. The world rife with conflict: belief and disbelief, secular pluralism and religious extremism, faith and reason, and all the hazy territory in between.

Mitchell Stephens, too, has been busy, grappling with all the above on Without Gods while trying to muster the opening chapters of his book — the blog serving as both helper and hindrance to his process (a fascinating paradox that haunts the book in the network). To reflect these busy times — and Mitch’s busy mind — the blog has undergone slight renovation, reflecting the busier layout of a newspaper while hopefully remaining accessible and easy to read.

There’s a tag cloud near the top serving as a sort of snapshot of Mitch’s themes and characters, while four topic areas to the side give the reader more options for navigating the site. In some ways the new design also reminds me of the clutter of a writer’s desk — a method-infused madness.

As templates were updated and wrinkles ironed out in the code, Mitch posted a few reflections on the pluses and pitfalls of this infant form, the blog:

Newspapers, too, began, in the 17th century, by simply placing short items in columns (in this case from top down). So it was possible to read on page four of a newspaper in England in 1655 that Cardinal Carassa is one of six men with a chance to become the next pope and then read on page nine of the same paper that Carassa “is newly dead.” Won’t we soon be getting similar chuckles out of these early blogs — where leads are routinely buried under supporting paragraphs; where whim is privileged, coherence discouraged; where the newly dead may be resurrected as one scrolls down.

Early newspapers eventually discovered the joys of what journalism’s first editor called a “continued relation.” Later they discovered layout.

Blogs have a lot of discovering ahead of them.

google: i’ll be your mirror

From notes accidentally published on Google’s website, leaked into the blogosphere (though here from the BBC): plans for the GDrive, a mirror of users’ hard drives.

With infinite storage, we can house all user files, including e-mails, web history, pictures, bookmarks, etc; and make it accessible from anywhere (any device, any platform, etc).

I just got a shiver — a keyhole glimpse of where this is headed. Google’s stock made a shocking dip last week after its Chief Financial Officer warned investors that growth of its search and advertising business would eventually slow down. The sudden panicked thought: how will Google realize its manifest destiny? You know: “organizing the world’s information and making it universally accessible (China notwithstanding) and useful”? How will it continue to feed itself?

Simple: storage.

Google, as it has already begun to do (Gmail, get off my back!), wants to organize our information and make it universally accessible and useful to us. No more worries about backing up data — Google’s got your back. No worries about saving correspondences — Google’s got those. They’ve got your shoebox of photographs, your file cabinet of old college papers, your bank records, your tax returns. All nicely organized and made incredibly useful.

But as we prepare for the upload of our lives, we might pause to ask: exactly how useful do we want to become?

RDF = bigger piles

Last week at a meeting of all the Mellon funded projects I heard a lot of discussion about RDF as a key technology for interoperability. RDF (Resource Description Framework) is a data model for machine readable metadata and a necessary, but not sufficient requirement for the semantic web. On top of this data model you need applications that can read RDF. On top of the applications you need the ability to understand the meaning in the RDF structured data. This is the really hard part: matching the meaning of two pieces of data from two different contexts still requires human judgement. There are people working on the complex algorithmic gymnastics to make this easier, but so far, it’s still in the realm of the experimental.

So why pursue RDF? The goal is to make human knowledge, implicit and explicit, machine readable. Not only machine readable, but automatically shareable and reusable by applications that understand RDF. Researchers pursuing the semantic web hope that by precipitating an integrated and interoperable data environment, application developers will be able to innovate in their business logic and provide better services across a range of data sets.

Why is this so hard? Well, partly because the world is so complex, and although RDF is theoretically able to model an entire world’s worth of data relationships, doing it seamlessly is just plain hard. You can spend time developing a RDF representation of all the data in your world, then someone else will come along with their own world, with their own set of data relationships. Being naturally friendly, you take in their data and realize that they have a completely different view of the category “Author,” “Creator,” “Keywords,” etc. Now you have a big, beautiful dataset, with a thousand similar, but not equivalent pieces. The hard part—determining relationships between the data.

We immediately considered how RDF and Sophie would work. RDF importing/exporting in Sophie could provide value by preparing Sophie for integration with other RDF capable applications. But, as always, the real work is figuring out what it is that people could do with this data. Helping users derive meaning from a dataset begs the question: what kind of meaning are we trying to help them discover? A universe of linguistic analysis? Literary theory? Historical accuracy? I think a dataset that enabled all of these would be 90% metadata, and 10% data. This raises another huge issue: entering semantic metadata requires skill and time, and is therefore relatively rare.

In the end, RDF creates bigger, better piles of data—intact with provenance and other unique characteristics derived from the originating context. This metadata is important information that we’d rather hold on to than irrevocably discard, but it leaves us stuck with a labyrinth of data, until we create the tools to guide us out. RDF is ten years old, yet it hasn’t achieved the acceptance of other solutions, like XML Schemas or DTD’s. They have succeeded because they solve limited problems in restricted ways and require relatively simple effort to implement. RDF’s promise is that it will solve much larger problems with solutions that have more richness and complexity; but ultimately the act of determining meaning or negotiating interoperability between two systems is still a human function. The undeniable fact of it remains— it’s easy to put everyone’s data into RDF, but that just leaves the hard part for last.

if:book-back mountain: emergent deconstruction

It’s Oscar weekend, and everyone seems to be thinking and talking about movies, including myself. At the institute we often talk about the discourse afforded by changes in technology, and it seems to be apropos to take a look at new forms of discourse in area of movies. A month or so ago, I was sent the viral Internet link of the week. Someone made a parody of the Brokeback Mountain trailer by taking its soundtrack and tag lines and remixng them with scenes from the flight school action movie, Top Gun. Tom Cruise and Val Kilmer are recast as gay lovers, misunderstood in the world of air to air combat. The technique of remixing a new trailer first appeared in 2005, with clips from the Shining recut as a romantic comedy to hilarious effect. With spot-on voiceover and Peter Gabriel’s “Solsbury Hill” as music, it similarly circulated the Internet, while consuming office bandwidth. The first Brokeback parody is uncertain, however, it inspired the p2p/ mashup (although some purists question whether these trailers are true mashup) community to create dozens of trailers. Virginia Heffernan in the New York Times gives a very good overview of the phenomenon, including the depictions of Fight Club, Heat, Lord of the Rings, and Stars War as a gay love story.

Some spoofs work better than others. The more successful trailers establish the parallels between the loner hero archetype of film and the outsider qualities of gay life. For example, as noted by Heffernana, Brokeback Heat, with limited extra editing, transforms Al Pacino and Robert DeNiro from a detective and criminal into lovers, who wax philosophically on the intrinsic nature of their lives and their lack of desire to live another way. Or in Top Gun 2: Brokeback Squadron, Tom Cruise and Val Kilmer exist in their own hyper-masculine reality outside of the understanding of others, in particular their female romantic counterparts. In Back to the Future, the relationship of mentor and hero is reinterpreted as a cross generational romance. Lord of the Rings: Brokeback Mount Doom successfully captures the analogy between the perilous journey of the hero and the experience of the disenfranchised. Here, the quest of Sam and Frodo is inverted into the quest to find the love that dares not speak its name. The p2p/ mashup community had come to the same conclusion (to, at times, great comic effect) that the gay community arrived at long ago, that male bonding (and its Hollywood representation) has a homoerotic subtext.

The loner heros found in the the Brokeback Mountain remixes are of particular interest. Over time, the successful parodies deconstruct the Hollywood imagery of the hero, and subsequently distill the archetypes of cinema. This process of distillation identifies key elements of the male hero. The common traits of the hero being that he lies outside the mainstream, cannot fight his rebel “nature”, often uses the guidance of a mentor and must travel a perilous journey of self discovery all rise to the surface of these new media texts. The irony plays out, when their hyper-masculinity are juxtaposed next to identical references of the supposed taboo gay experience.

On the other hand, the Arrested Development version contains titles thanking the cast and producers of the cancelled series, clips of Jason Bateman’s television family suggesting his latent homosexuality, and the Brokeback Mountain theme music. The disparate pieces make less sense, rendering it ultimately less interesting as a whole. Likewise, Brokeback Ranger, a riff on Chuck Norris in the Walker, Texas Ranger television series, is a collection of clips of the Norris fighting and solving crimes, with the prerequisite music, and titles that describe Norris ironic superhuman abilities including dividing by zero. Again, the references are not of the hero archetype and the piece, although mildly humorous, has limited depth.

A potentially new form of discourse is being created, in which the archetypes of media text emerge from their repeated deconstruction and subsequent reconstruction. From these works, an understanding of the media text appears through an emergent deconstruction. In that, the individual efforts need not be conscious or even intended. Rather, the funniest and most compelling examples are the remixes which correctly identify and utilize the traditional conventions in the media text. Therefore, their success is directly correlated to their ability to correctly identify the archetype.

The users may not have prior knowledge of the ideas of the hero described by Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Nor are they required to have read Umberto Eco’s deconstruction of James Bond, or Leslie Fiedler’s work on the homosexual subtext found in the novel. Further, each individual remix author does not need to set out to define the specific archetypes. What is most extraordinary is that their aggregate efforts gravitate towards the distilled archetype, in this case, the male bonding rituals of the hero in cinema. Some examples will miss the themes, which is inherent in all emergent systems. By the definition and nature of archetypes, the work that most resonate are the ones which most convincingly identify, reference, (and in this case, parody) the archetype. These analyses can be discovered by an individual, as Campbell, Eco, Jung and Fiedler did. Since their groundbreaking works, there is an abundance of deconstructing media text from the last fifty years. Here, the lack of intention, and the emergence of the archetypes through the aggregate is new. An important aspect of these aggregate analyses is that they could only come about through the wide availability of both access to the network and to digital video editing software.

At the institute, we expect that the dissemination of authoring tools and access to the network will lead to new forms of discourse and we look for occurrences of them. Emergent deconstruction is still in its early stages. I am excited by its prospects, but how far it can meaningfully grow is unclear. However, I do know that after watching thirty some versions of the Brokeback Mountain remixed trailers, I do not need to hear its moody theme music any more, but I suppose that is part of the process of emergent forms.

post-doc fellowships available for work with the institute

The Institute for the Future of the Book is based at the Annenberg Center for Communication at USC. Jonathan Aronson, the executive director of the center, has just sent out a call for eight post-docs and one visiting scholar for next year. if you know of anyone who would like to apply, particularly people who would like to work with us at the institute, please pass this on. the institute’s activities at the center are described as follows:

Shifting Forms of Intellectual Discourse in a Networked Culture

For the past several hundred years intellectual discourse has been shaped by the rhythms and hierarchies inherent in the nature of print. As discourse shifts from page to screen, and more significantly to a networked environment, the old definitions and relations are undergoing unimagined changes. The shift in our world view from individual to network holds the promise of a radical reconfiguration in culture. Notions of authority are being challenged. The roles of author and reader are morphing and blurring. Publishing, methods of distribution, peer review and copyright — every crucial aspect of the way we move ideas around — is up for grabs. The new digital technologies afford vastly different outcomes ranging from oppressive to liberating. How we make this shift has critical long term implications for human society.

Research interests include: how reading and writing change in a networked culture; the changing role of copyright and fair use, the form and economics of open-source content, the shifting relationship of medium to message (or form to content).

if you have any questions, please feel free to email bob stein

thinking about blogging 2: democracy

Banning books may be easy, but banning blogs is an exhausting game of Whack-a-Mole for politically repressive regimes like China and Iran.

Farid Pouya, recapping recent noteworthy posts from the Iranian blogosphere last week on Global Voices, refers to one blogger’s observations on the chilled information climate under president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad:

Andishe No (means New Thought) fears that country was pushed back to pre Khatami’s period concerning censorship. He believes that even if many books get banned in twenty first century, government can not stop people getting information. Government wants to control weblogs in Iran and put them in a guideline.

Unlike the fleas that swarm American media and politics, Iran’s cyber-dissidents frequently are the sole conduit for uncensored information — an underground army of chiseler’s, typing away at the barricades. Here we see the blog as a building block for civil society. Electronic samizdat. Basic life forms in a free media ecology, instilling new habits in both writers and readers: habits of questioning, of digging deeper. Individual sites may get shut down, individual bloggers may be jailed but the information finds a way.

Though the situation in Iran is far from enviable, there is something attractive about the moral clarity of its dissident blogging. If one wants the truth, one must find alternatives — it’s that simple. But with alternative media in the United States — where the media ecology is highly developed and corruption more subtle — it’s hard to separate the wheat from the chaff. Political blogs in America may resound with outrage and indignation, but it’s the kind that comes from a life of abundance. All too often, political discourse is not something that points toward action, but an idle picking at the carcass of liberty.

Sure, we’ve seen blogs make a difference in politics (Swift Boats, Rathergate, Trent Lott — 2004 was the “year of the blog”), but generally as a furtherance of partisan aims — a way of mobilizing the groundtroops within a core constituency that has already decided what it believes.

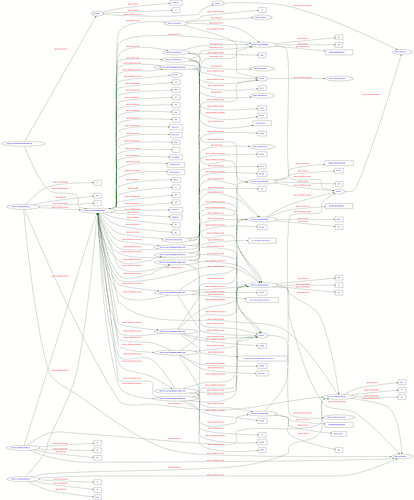

When one looks at this map (admittedly a year old) of the American political blogosphere, one notes with dismay that there are in fact two spheres, mapping out all too cleanly to the polarized reality on the ground. One begins to suspect that America’s political blogs are merely a pressure valve for a population that, though ill at ease, is still ultimately paralyzed.