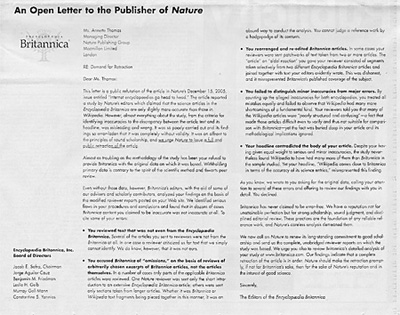

The Encyclopedia Britannica versus Wikipedia saga continues. As Ben has recently posted, Britannica has been confronting Nature on its article which found that the two encyclopedias were fairly equal in the accuracy of their science articles. Today, the editors and the board of directors of Encyclopedia Britannica, have taken out a half page ad in today New York Times (A19) to present an open letter to Nature which requests for a public reaction of the article.

The Encyclopedia Britannica versus Wikipedia saga continues. As Ben has recently posted, Britannica has been confronting Nature on its article which found that the two encyclopedias were fairly equal in the accuracy of their science articles. Today, the editors and the board of directors of Encyclopedia Britannica, have taken out a half page ad in today New York Times (A19) to present an open letter to Nature which requests for a public reaction of the article.

Several interesting things are going on here. Because Britannica chose to place an ad in the Times, it shifted the argument and debate away from the peer review / editorial context into one of rhetoric and public relations. Further, their conscious move to take the argument to the “public” or the “masses” with an open letter is ironic because the New York TImes does not display its print ads online, therefore access of the letter is limited to the Time’s print readership. (Not to mention, the letter is addressed to the Nature Publishing Group located in London. If anyone knows that a similar letter was printed in the UK, please let us know.) Readers here can click on the thumbnail image to read the entire text of the letter. Ben raised an interesting question here today, asking where one might post a similar open letter on the Internet.

Britannica cites many important criticisms of Nature’s article, including: using text not from Britannica, using excerpts out of context, giving equal weight to minor and major errors, and writing a misleading headline. If their accusations are true, then Nature should redo the study. However, to harp upon Nature’s methods is to miss the point. Britannica cannot do anything to stop Wikipedia, except to try to discredit to this study. Disproving Nature’s methodology will have a limited effect on the growth of Wikipedia. People do not mind that Wikipedia is not perfect. The JKF assassination / Seigenthaler episode showed that. Britannica’s efforts will only lead to more studies, which will inevitably will show errors in both encyclopedias. They acknowledge in today’s letter that, “Britannica has never claimed to be error-free.” Therefore, they are undermining their own authority, as people who never thought about the accuracy of Britannica are doing just that now. Perhaps, people will not mind that Britannica contains errors as well. In their determination to show the world that of the two encyclopedias which both content flaws, they are also advertising that of the two, the free one has some-what more errors.

In the end, I agree with Ben’s previous post that the Nature article in question has a marginal relevance to the bigger picture. The main point is that Wikipedia works amazingly well and contains articles that Britannica never will. It is a revolutionary way to collaboratively share knowledge. That we should give consideration to the source of our information we encounter, be it the Encyclopedia Britannica, Wikipedia, Nature or the New York Time, is nothing new.

Monthly Archives: March 2006

if not rdf, then what?: part II

I had an exchange about my previous post with an RDF expert who explained to me that API’s are not like RDF and it would be incorrect to try to equate them. She’s right – API’s do not replace the need for RDF, nor do they replicate the functionality of RDF. API’s do provide access to data, but that data can be in many forms, including XML bound RDF. This is one of the pleasures and priviledges of writing on this blog: the audience contributes at a very high level of discourse, and is endowed with extremely deep knowledge about the topics under discussion.

I want to reiterate my point with a new inflection. By suggesting that API’s were an alternative to RDF, I was trying to get at a point that had more to do with adoption than functionality. I admit, I did not make the point well. So let me make a second attempt: API’s are about data access, and that, currently (and from my anecdotal experience) is where the value proposition lies for the new breed of web services. You have your data in someone’s database. That data is accessible to developers to manipulate and represent back to you in new, innovative, and useful ways. Most of the attention in the webdev community is turning towards the development of new interfaces—not towards the development of new tools to manage and enrich the data (again, anecdotal evidence only). Yes, there are people still interested in semantic data; we are indebted to them for continuing to improve the way our systems interact at a data level. But the focus of development has shifted to the interface. API’s make the gathering of data as simple as setting parameters, leaving only the work of designing the front-end experience.

Another note on RDF from my exchange: it was pointed out that practitioners of RDF prefer not to read it in XML, but instead use Notation 3 (N3), which is undeniably easier to read than XML. I don’t know enough about N3 to make a proper example, but I think you can get the idea if you look at the examples here and here.

next text: new media in history teaching and scholarship

The next text project came forth from the realization that twenty-five years into the application of new media to teaching and learning, textbooks have not fully tapped the potential of new media technology. As part of this project, we have invited leading scholars and practitioners of educational technology from specific disciplines to attend meetings with their peers and the institute. Yesterday, we were fortunate to spend the day talking to a group of American History teachers and scholars, some of whom created seminal works in history and new media. Over the course of the day, we discussed their teaching, their scholarship, the creation and use of textbooks, new media, and how to encourage the birth of the next generation born digital textbook. By of the end of the day, the next text project started to take a concrete form. We began to envision the concept of accessing the vast array of digitized primary documents of American History that would allow teachers to formulate their own curricula or use guides that were created and vetted by established historians.

Attendees included:

David Jaffe, City University of New York

Gary Kornblith, Oberlin College

John McClymer, Assumption College

Chad Noyes, Pierrepont School

Jan Reiff, University of California, Los Angeles

Carl Smith, Northwestern University

Jim Sparrow, University of Chicago

Roy Rosenzweig, George Mason University

Kate Wittenberg, EPIC, Columbia University

The group contributed to influential works in the field of History and New Media, including Who Built America, The Great Chicago Fire and The Web of Memory, The Encyclopedia of Chicago, the Blackout History Project, the Visual Knowledge Project, History Matters,the Journal of American History Textbook and Teaching Section, and the American History Association Guide to Teaching and Learning with New Media.

Almost immediately, we found that their excellence in their historical scholarship was equally matched in their teaching. Often their introductions to new media came from their own research. Online and digital copies of historical documents radically changed the way they performed their scholarship. It then fueled the realization that these same tools afforded the opportunity for students to interact with primary documents in a new way which was closer to how historians work. Often, our conversations gravitated back to teaching and students, rather than purely technical concerns. Their teaching led them to the forefront of developing and promoting active learning and constructionist pedagogies, by encouraging an environment of inquiry-based learning, rather than rote memorization of facts, through the use of technology. In these new models, students are guided to multiple paths of self-discovery in their learning and understanding of history.

We spoke at length on the phrase coined by attendee John McClymer, “the pedagogy of abundance.” With access to rich archives of primary documents of American history as well as narratives, they are not faced with the problems of

The discussion also included issues of resistance, which were particularly interesting to us. Many meeting participants mentioned student resistance to new methods of learning including both new forms of presentation and inquiry-based pedagogies. In that, traditional textbooks are portable and offer an established way to learn. They noted an institutional tradition of the teacher as the authoritative interpreter in lecture-based teaching, which is challenged by active learning strategies. Further, we discussed the status (or lack of) of the group’s new media endeavors in both their scholarship and teaching. Depending upon their institution, using new media in their scholarship had varying degrees of importance in their tenure and compensation reviews from none to substantial. Quality of teaching had no influence in these reviews. Therefore, these projects were often done, not in lieu of, but in addition to their traditional publishing and academic professional requirements.

The combination of an abundance of primary documents (particulary true for American history) and a range of teaching goals and skills led to the idea of adding layers on top of existing digital archives. Varying layers could be placed on top of these resources to provide structure for both teachers and students. Teachers who wanted to maintain the traditional march through the course would still be able to do so through guides created by the more creative teacher. Further, all teachers would be able to control the vast breadth of material to avoid overwhelming students and provide scaffolding for their learning experience. We are very excited by this notion, and will further refine the meeting’s groundwork to strategize how this new learning environment might get created.

We are still working through everything that was discussed, however, we left the meeting with a much clearer idea of the landscape of the higher education history teacher / scholar, as well as, possible directions that the born digital history textbook could take.

the social life of books

One of the most exciting things about Sophie, the open-source software the institute is currently developing, is that it will enable readers and writers to have conversations inside of books — both live chats and asynchronous exchanges through comments and social annotation. I touched on this idea of books as social software in my most recent “The Book is Reading You” post, and we’re exploring it right now through our networked book experiments with authors Mitch Stephens, and soon, McKenzie Wark, both of whom are writing books and opening up the process (with a little help from us) to readers. It’s a big part of our thinking here at the institute.

Catching up with some backlogged blog reading, I came across a little something from David Weinberger that suggests he shares our enthusiasm:

I can’t wait until we’re all reading on e-books. Because they’ll be networked, reading will become social. Book clubs will be continuous, global, ubiquitous, and as diverse as the Web.

And just think of being an author who gets to see which sections readers are underlining and scribbling next to. Just think of being an author given permission to reply.

I can’t wait.

Of course, ebooks as currently envisioned by Google and Amazon, bolted into restrictive IP enclosures, won’t allow for this kind of exchange. That’s why we need to be thinking hard right now about an alternative electronic publishing system. It may seem premature to say this — now, when electronic books are a marginal form — but before we know it, these companies will be the main purveyors of all media, including books, and we’ll wonder what the hell happened.

academic publishing as “gift culture”

John Holbo has an excellent piece up on the Valve that very convincingly argues the need to reinvent scholarly publishing as a digital, networked system. John will be attending a meeting we’ve organized in April to discuss the possible formation of an electronic press — read his post and you’ll see why we’ve invited him.

It was particularly encouraging, in light of recent discussion here, to see John clearly grasp the need for academics to step up to the plate and take into their own hands the development of scholarly resources on the web — now more than ever, as Google, Amazon are moving more aggressively to define how we find and read documents online:

…it seems to me the way for academic publishing to distinguish itself as an excellent form – in the age of google – is by becoming a bastion of ‘free culture’ in a way that google book won’t. We live in a world of Amazon ‘search inside’, but also of copyright extension and, in general, excessive I.P. enclosures. The groves of academe are well suited to be exemplary Creative Commons. But there is no guarantee they will be. So we should work for that.

britannica bites back (do we care?)

![]() Late last year, Nature Magazine let loose a small shockwave when it published results from a study that had compared science articles in Encyclopedia Britannica to corresponding entries in Wikipedia. Both encyclopedias, the study concluded, contain numerous errors, with Britannica holding only a slight edge in accuracy. Shaking, as it did, a great many assumptions of authority, this was generally viewed as a great victory for the five-year-old Wikipedia, vindicating its model of decentralized amateur production.

Late last year, Nature Magazine let loose a small shockwave when it published results from a study that had compared science articles in Encyclopedia Britannica to corresponding entries in Wikipedia. Both encyclopedias, the study concluded, contain numerous errors, with Britannica holding only a slight edge in accuracy. Shaking, as it did, a great many assumptions of authority, this was generally viewed as a great victory for the five-year-old Wikipedia, vindicating its model of decentralized amateur production.

Now comes this: a document (download PDF) just published on the Encyclopedia Britannica website claims that the Nature study was “fatally flawed”:

Almost everything about the journal’s investigation, from the criteria for identifying inaccuracies to the discrepancy between the article text and its headline, was wrong and misleading.

What are we to make of this? And if Britannica’s right, what are we to make of Nature? I can’t help but feel that in the end it doesn’t matter. Jabs and parries will inevitably be exchanged, yet Wikipedia continues to grow and evolve, containing multitudes, full of truth and full of error, ultimately indifferent to the censure or approval of the old guard. It is a fact: Wikipedia now contains over a million articles in english, nearly 223 thousand in Polish, nearly 195 thousand in Japanese and 104 thousand in Spanish; it is broadly consulted, it is free and, at least for now, non-commercial.

At the moment, I feel optimistic that in the long arc of time Wikipedia will bend toward excellence. Others fear that muddled mediocrity can be the only result. Again, I find myself not really caring. Wikipedia is one of those things that makes me hopeful about the future of the web. No matter how accurate or inaccurate it becomes, it is honest. Its messiness is the messiness of life.

vive le interoperability!

A smart column in Wired by Leander Kahney explains why France’s new legislation prying open the proprietary file format lock on iPods and other entertainment devices is an important stand taken for the public good:

A smart column in Wired by Leander Kahney explains why France’s new legislation prying open the proprietary file format lock on iPods and other entertainment devices is an important stand taken for the public good:

French legislators aren’t just looking at Apple. They’re looking ahead to a time when most entertainment is online, a shift with profound consequences for consumers and culture in general. French lawmakers want to protect the consumer from one or two companies holding the keys to all of its culture, just as Microsoft holds the keys to today’s desktop computers.

Apple, by legitimizing music downloading with iTunes and the iPod, has been widely credited with making the internet safe for the culture industries after years of hysteria about online piracy. But what do we lose in the bargain? Proprietary formats lock us into specific vendors and specific devices, putting our media in cages. By cornering the market early, Apple is creating a generation of dependent customers who are becoming increasingly shackled to what one company offers them, even if better alternatives come along. France, on the other hand, says let everything be playable on everything. Common sense says they’re right.

Now Apple is the one crying piracy, calling France the great enabler. While I agree that piracy is a problem if we’re to have a functioning cultural economy online, I’m certain that proprietary controls and DRM are not the solution. In the long run, they do for culture what Microsoft did for software, creating unbreakable monopolies and placing unreasonable restrictions on listeners, readers and viewers. They also restrict our minds. Just think of the cumulative cognitive effect of decades of bad software Microsoft has cornered us into using. Then look at the current ipod fetishism. The latter may be more hip, but they both reveal the same narrowed thinking.

One thing I think the paranoid culture industries fail to consider is that piracy is a pain in the ass. Amassing a well ordered music collection through illicit means is by no means easy — on the contrary, it can be a tedious, messy affair. Far preferable is a good online store selling mp3s at reasonable prices. There you can find stuff quickly, be confident that what you’re getting is good and complete, and get it fast. Apple understood this early on and they’re still making a killing. But locking things down in a proprietary format takes it a step too far. Keep things open and may the best store/device win. I’m pretty confident that piracy will remain marginal.

googlezon and the publishing industry: a defining moment for books?

Yesterday Roger Sperberg made a thoughtful comment on my latest Google Books post in which he articulated (more precisely than I was able to do) the causes and potential consequences of the publisher’s quest for control. I’m working through these ideas with the thought of possibly writing an article, so I’m reposting my response (with a few additions) here. Would appreciate any feedback…

What’s interesting is how the Google/Amazon move into online books recapitulates the first flurry of ebook speculation in the mid-to-late 90s. At that time, the discussion was all about ebook reading devices, but then as now, the publish industry’s pursuit of legal and techological control of digital books seemed to bring with it a corresponding struggle for control over the definition of digital books — i.e. what is the book going to become in the digital age? The word “ebook” — generally understood as a digital version of a print book — is itself part of this legacy of trying to stablize the definition of books amid massively destablizing change. Of course the problem with this is that it throws up all sorts of walls — literal and conceptual — that close off avenues of innovation and rob books of much of their potential enrichment in the electronic environment.

Clifford Lynch described this well in his important 2001 essay “The Battle to Define to Define the Future of the Book in the Digital World”:

Clifford Lynch described this well in his important 2001 essay “The Battle to Define to Define the Future of the Book in the Digital World”:

…e-book readers may be the price that the publishing industry imposes, or tries to impose, on consumers, as part of the bargain that will make large numbers of interesting works available in electronic form. As a by-product, they may well constrain the widespread acceptance of the new genres of digital books and the extent to which they will be thought of as part of the canon of respectable digital “printed” works.

A similar bargain is being struck now between publishers and two of the great architects of the internet: Google and Amazon. Naturally, they accept the publishers’ uninspired definition of electronic books — highly restricted digital facsimiles of print books — since it guarantees them the most profit now. But it points in the long run to a malnourished digital culture (and maybe, paradoxically, the persistence of print? since paper books can’t be regulated so devilishly).

As these companies come of age, they behave less and less like the upstart innovators they originally were, and more like the big corporations they’ve become. We see their grand vision (especially Google’s) contract as the focus turns to near-term success and the fluctuations of stock. It creates a weird paradox: Google Book Search totally revolutionizes the way we search and find connections between books, but amounts to a huge setback in the way we read them.

(For those of you interested in reading Lynch’s full essay, there’s a TK3 version that is far more comfortable to read than the basic online text. Click the image above or go here to download. You’ll have to download the free TK3 Reader first, which takes about 10 seconds. Everything can be found at the above link).

copyright debates continues, now as a comic book

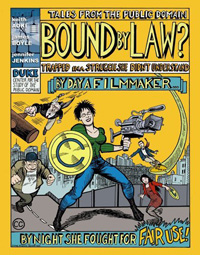

Keith Aoki, James Boyle and Jennifer Jenkins have produced a comic book entitled, “Bound By Law? Trapped in a Sturggle She Didn’t Understand” which portrays a fictional documentary filmmaker who learns about intellectual property, copyright and more importantly her rights to use material under fair use. We picked up a copy during the recent conference on “Cultural Environmentalism at 10” at Stanford. This work was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, the same people who funded “Will Fair Use Survive?” from the Free Expression Policy Project of the Brennan Center at the NYU Law School, which was discussed here upon its release. The comic book also relies on the analysis that Larry Lessig covered in “Free Culture.” However, these two works go into much more detail and have quite different goals and audiences. With that said, “Bound By Law” deftly takes advantage of the medium and boldly uses repurposed media iconic imagery to convey what is permissible and to explain the current chilling effect that artists face even when they have a strong claim of fair use.

Keith Aoki, James Boyle and Jennifer Jenkins have produced a comic book entitled, “Bound By Law? Trapped in a Sturggle She Didn’t Understand” which portrays a fictional documentary filmmaker who learns about intellectual property, copyright and more importantly her rights to use material under fair use. We picked up a copy during the recent conference on “Cultural Environmentalism at 10” at Stanford. This work was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, the same people who funded “Will Fair Use Survive?” from the Free Expression Policy Project of the Brennan Center at the NYU Law School, which was discussed here upon its release. The comic book also relies on the analysis that Larry Lessig covered in “Free Culture.” However, these two works go into much more detail and have quite different goals and audiences. With that said, “Bound By Law” deftly takes advantage of the medium and boldly uses repurposed media iconic imagery to convey what is permissible and to explain the current chilling effect that artists face even when they have a strong claim of fair use.

Part of Boyle’s original call ten years ago for a Cultural Environmentalism Movement was to shift the discourse of IP into the general national dialogue, rather than remain in the more narrow domain of legal scholars. To that end, the logic behind capitalizing on a popular culture form is strategically wise. In producing a comic book, the authors intend to increase awareness among the general public as well as inform filmmakers of their rights and the current landscape of copyright. Using the case study of documentary film, they cite many now classic copyright examples (for example the attempt to use footage of a television in the background playing the”Simpsons” in a documentary about opera stagehands.) “Bound By Law” also leverages the form to take advantage of compelling and repurposed imagery (from Mickey Mouse to Mohammed Ali) to convey what is permissible and the current chilling effect that artists face in attempting to deal with copyright issues. It is unclear if and how this work will be received in the general public. However, I can easily see this book being assigned to students of filmmaking. Although, the discussion does not forge new ground, its form will hopefully reach a broader audience. The comic book form may still be somewhat fringe for the mainstream populus and I hope for more experiments in even more accesible forms. Perhaps the next foray into the popular culture will an episode of CSI or Law & Order, or a Michael Crichton thriller.

relentless abstraction

Quite surprisingly, Michael Crichton has an excellent op-ed in the Sunday Times on the insane overreach of US patent law, the limits of which are to be tested today before the Supreme Court. In dispute is the increasingly common practice of pharmaceutical companies, research labs and individual scientists of patenting specific medical procedures or tests. Today’s case deals specifically with a basic diagnostic procedure patented by three doctors in 1990 that helps spot deficiency in a certain kind of Vitamin B by testing a patient’s folic acid levels.

Quite surprisingly, Michael Crichton has an excellent op-ed in the Sunday Times on the insane overreach of US patent law, the limits of which are to be tested today before the Supreme Court. In dispute is the increasingly common practice of pharmaceutical companies, research labs and individual scientists of patenting specific medical procedures or tests. Today’s case deals specifically with a basic diagnostic procedure patented by three doctors in 1990 that helps spot deficiency in a certain kind of Vitamin B by testing a patient’s folic acid levels.

Under current laws, a small royalty must be paid not only to perform the test, but to even mention it. That’s right, writing it down or even saying it out loud requires payment. Which means that I am in violation simply for describing it above. As is the AP reporter whose story filled me in on the details of the case. And also Michael Crighton for describing the test in his column (an absurdity acknowledged in his title: “This Essay Breaks the Law”). Need I (or may I) say more?

And patents can reach far beyond medical procedures that prevent diseases. They can be applied to the diseases themselves, even to individual genes. Crichton:

…the human genome exists in every one of us, and is therefore our shared heritage and an undoubted fact of nature. Nevertheless 20 percent of the genome is now privately owned. The gene for diabetes is owned, and its owner has something to say about any research you do, and what it will cost you. The entire genome of the hepatitis C virus is owned by a biotech company. Royalty costs now influence the direction of research in basic diseases, and often even the testing for diseases. Such barriers to medical testing and research are not in the public interest. Do you want to be told by your doctor, “Oh, nobody studies your disease any more because the owner of the gene/enzyme/correlation has made it too expensive to do research?”

It seems everything — even “laws of nature, natural phenomena and abstract ideas” (AP) — is information that someone can own. It goes far beyond the digital frontiers we usually talk about here. Yet the expansion of the laws of ownership — what McKenzie Wark calls “the relentless abstraction of the world” — essentially digitizes everything, and everyone.