As noted in The New York Times, Harper-Collins has put the text of Bruce Judson’s Go It Alone: The Secret to Building a Successful Business on Your Own online; ostensibly this is a pilot for more books to come.

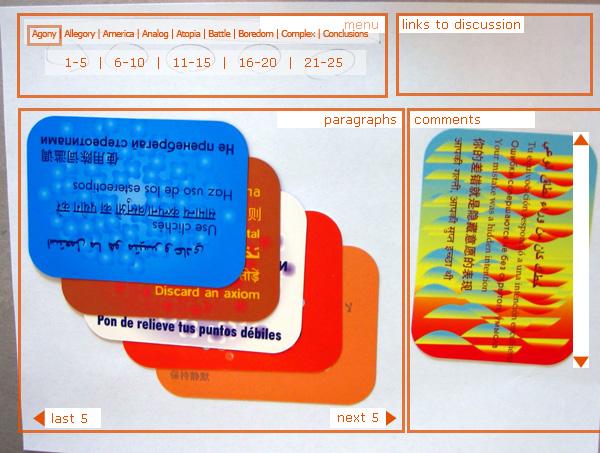

Harper-Collins isn’t doing this out of the goodness of their hearts: it’s an ad-supported project. Every page of the book (it’s paginated in exactly the same way as the print edition) bears five Google ads, a banner ad, and a prominent link to buy the book at Amazon. Visiting Amazon suggests other motives for Harper-Collins’s experiment: new copies are selling for $5.95 and there are no reader reviews of the book, suggesting that, despite what the press would have you believe, Judson’s book hasn’t attracted much attention in print format. Putting it online might not be so much of a brave pilot program as an attempt to staunch the losses for a failed book.

Certainly H-C hasn’t gone to a great deal of trouble to make the project look nice. As mentioned, the pagination is exactly the same as the print version; that means that you get pages like this, which start mid-sentence and end mid-sentence. While this is exactly what print books do, it’s more of a problem on the web: with so much extraneous material around it, it’s more difficult for the reader to remember where they were. It wouldn’t have been that hard to rebreak the book: on page 8, they could have left the first line on the previous page with the paragraph it belongs too while moving the last line to the next page.

It is useful to have a book that can be searched by Google. One suspects, however, that Google would have done a better job with this.