The following post comes from my friend Sally Northmore, a writer and designer based in New York who lately has been interested in things like animation, video game theory, and (right up our alley) the materiality of books and their transition to a virtual environment. A couple of weeks ago we were talking about the British Library’s rare manuscript digitization project, “Turning the Pages” — something I’d been meaning to discuss here but never gotten around to doing. It turns out Sally had some interesting thoughts about this so I persuaded her to do a brief write-up of the project for if:book. Which is what follows below. Come to think of it, this is especially interesting when juxtaposed with Bob’s post earlier this week on Jefferson Han’s amazing gestural interface design. Here’s Sally… – Ben

The British Library’s collaboration with multimedia impresarios at Armadillo Systems has led to an impressive publishing enterprise, making available electronic 3-D facsimiles of their rare manuscript collection.

“Turning the Pages”, available in CD-ROM, online, and kiosk format, presents the digital incarnation of these treasured texts, allowing the reader to virtually “turn” the pages with a touch and drag function, “pore over” texts with a magnification function, and in some cases, access extras such as supplementary notes, textual secrets, and audio accompaniment.

Pages from Mozart’s thematic catalogue — a composition notebook from the last seven years of his life. Allows the reader to listen to works being discussed.

The designers ambitiously mimicked various characteristics of each work in their 3-D computer models. For instance, the shape of a page of velum turning differs from the shape of a page of paper. It falls at a unique speed according to its weight; it casts a unique shadow. The simulation even allows for a discrepancy in how a page would turn depending on what corner of the page you decide to peel from.

Online visitors can download a library of manuscripts in Shockwave although these versions are a bit clunkier and don’t provide the flashier thrills of the enormous touch screen kiosks the British Library now houses.

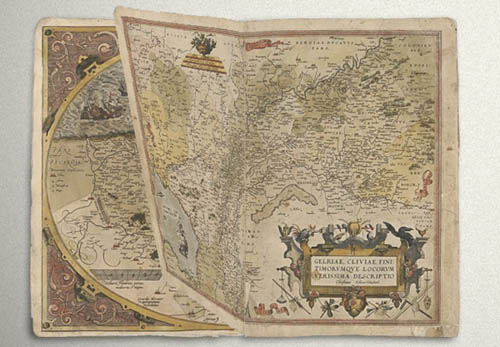

Mercator’s first atlas of Europe – 1570s

Online, the “Turning the Pages” application forces you to adapt to the nature of its embodiment–to physically re-learn how to use a book. A hand cursor invites the reader to turn each page with a click-and-drag maneuver of the mouse. Sounds simple enough, but I struggled to get the momentum of the drag just right so that the page actually turned. In a few failed attempts, the page lifted just so… only to fall back into place again. Apparently, if you can master the Carpal Tunnel-inducing rhythm, you can learn to manipulate the page-turning function even further, grabbing multiple of pages at once for a faster, abridged read.

The value of providing high resolution scans of rare editions of texts for the general public to experience, a public that otherwise wouldn’t necessarily ever “touch” say, the Lindisfarne Gospels, doesn’t go without kudos. Hey, democratic right? Armadillo Systems provides a list of compelling raisons d’être on their site to this effect. But the content of these texts is already available in reprintable (democratic!) form. Is the virtual page-turning function really necessary for greater understanding of these works, or a game of academic scratch-n-sniff?

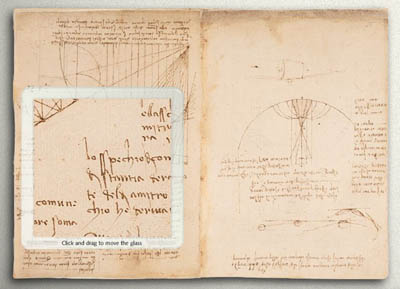

The “enlarge” function even allows readers to reverse the famous mirror writing in Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks

At the MLA conference in D.C. this past December, where the British Library had set up a demonstration of “Turning the Pages”, this was the question most frequently asked of the BL’s representative. Who really needs to turn the pages? I learned from the rep’s response that, well, nobody does! Scholars are typically more interested studying the page, and the turning function hasn’t proven to enhance or revive scholarly exploration. And surely, the Library enjoyed plenty of biblio-clout and tourist traffic before this program?

But the lure of new, sexy technology can’t be underestimated. From what I understood, the techno-factor is an excellent beacon for attracting investors and funding in multimedia technology. Armadillo’s web site provides an interesting sales pitch:

By converting your manuscripts to “Turning the Pages” applications you can attract visitors, increase website traffic and add a revenue stream – at the same time as broadening access to your collection and informing and entertaining your audience.

The program reveals itself to be a peculiar exercise, tangled in its insistence on fetishizing aspects of the material body of the text–the weight of velum, the karat of gold used to illuminate, the shape of the binding. Such detail and love for each material manuscript went into this project to recreate, as best possible, the “feel” of handling these manuscripts.

Under ideal circumstances, what would the minds behind “Turning the Pages” prefer to create? The original form of the text–the “alpha” manuscript–or the virtual incarnation? Does technological advancement seduce us into valuing the near-perfect simulation over the original? Are we more impressed by the clone, the “Dolly” of hoary manuscripts? And, would one argue that “Turning the Pages” is the best proxy for the real thing, or, another “thing” entirely?

This is a lovely post, more please.

This reminds me, kinda, of an old and poorly explained post of mine where I tried to make the argument that pages as they exist in print books might be seen as an evolutionary afterthought in the greater history of the book. When you’re making a codex book (a spine with a lot of pages), you have pages (of the same shape, of the same size, for example) because that’s the easiest way to do it. When you make an electronic analogue (like the ones you’re describing) you’re only limited to pages of a certain size and shape if you’re constraining yourself to that size and shape of pages. In a virtual world, for example, it’s just as easy to make a book with star-shaped pages as it is to make a book with rectangular pages.

Certainly we’re used to pages and how they function in books, but I don’t think they have a teleological purpose. I am curious to see what happens to pages . . .

That’s really interesting to think of the evolutionary or teleological purpose of the page and the form of what we communicate information through. That reminds me of something N. Katherine Hayles writes on — the “skeuomorph”. The skeuomorph, she writes, “is a design feature that is no longer functional in itself but that refers back to a feature that was functional at an earlier time… …Skeuomorphs visibly testify to the social or psychological necessity for innovation to be tempered by replication.”

The turning function in “Turning the Pages” could be seen as a skeuomorph as much as, say, a plastic limb prosthesis. There’s no apparent functional point in it, but perhaps it serves as a comforting

reminder of the original. At least more comforting than other types of prostheses. Or maybe there is something comforting in a slow, visible, evolutionary process as opposed to a hasty jump into a new representation.

as an e-book programmer, i was

quick to dismiss turning-pages.

_especially_ the bad imitations,

which took a second or more.

ick! too slow! what’s the point?

but i must say on new machines,

where it works very quickly, i am

jealous of zinio’s turning-page.

first of all, it looks pretty good.

i also find a visible signal of a turn

is useful for the accidental situation

where you leave a key pressed down,

inadvertently turning 2 pages, not 1.

without feedback, you can miss those.

ditto on accidently going the wrong way.

zinio’s multiple-page-turn on a jump

to a distant page is informative as well.

i still have not incorporated a page-turn

into my own programs, no, but i _might_!

i would — as zinio does — give users the

option to turn it off, but for the most part,

i don’t see that it causes any real _harm_.

and i’ve come around to the position that

verisimilitude between e-book and p-book

is not only not a bad thing, but _desireable_,

for reasons of comfort and active adoption,

as well as tight synergy between an e-book

and its “twin” whenever it gets printed out.

i want people to be able to “forget” whether

they’re looking at a paper-book or an e-book.

because, really, what difference should it make?

(except for the fact hotlinks don’t work when you

“click them” with your finger in a paper-book…) :+)

i’m still not convinced e-books need to be 3d,

because that seems to stretch it to unnecessary,

but when machines are fast enough to do _that_,

i suppose i won’t find myself objecting then either.

i probably won’t ever put a “stained page” capability

in my e-book apps, as that seems counterproductive.

but i _have_ programmed an “analog bookmark” thingee

that — unlike my digital bookmarks but _just_like_ their

analog cousins — “fall out of the book” ~10% of the time,

causing the reader to “lose their place”. :+)

-bowerbird

Bowerbird–

i also find a visible signal of a turn is useful for the accidental situation where you leave a key pressed down, inadvertently turning 2 pages, not 1. without feedback, you can miss those.

ditto on accidently going the wrong way.

I feel you on this–visual cues pinned to functions help me, as does feedback. But, it bothers me for reasons I can’t accurately pin down yet, to call the e-book a twin.

What I wonder is how readers will assign or tag on feelings of ownership/attachment to an e-book as they do to a print. Depending on the text (favorite, or not / contemporary or classic) I like to own a new clean copy, or an interesting used edition, or maybe even a scuffed up, coffee stained copy I found on someone’s stoop.

How could I own a *used* or vintage copy of an ebook? How do you measure its character or life?

Hey, do you have an example of the analog bookmark online? I’d like to check it out.

sally said:

> it bothers me for reasons I can’t accurately pin down yet,

> to call the e-book a twin.

when you pin those reasons down, share them… :+)

(i don’t think today’s e-books are true enough to

their p-book counterparts to instantiate “twins” in

people’s minds, but i think that’s what we need…)

> What I wonder is how readers will assign

> or tag on feelings of ownership/attachment

> to an e-book as they do to a print.

“ownership” and “attachment” strike me as

two different things. then again, maybe i’ve

been a poverty-stricken poet for too long for

the materialistic urge to mean much any more.

still, for me, that bond is mental, not physical.

(so, for instance, i have it for some websites,

one of them now being sofake.com, which you

brought to my attention in another thread here.

thank you so much for that great pointer!)

> Hey, do you have an example of the

> analog bookmark online? I’d like to check it out.

nah, just as idea i threw into one of my prototypes

as a nod to my strange sense of humor… :+)

-bowerbird

Sally said:

> What I wonder is how readers will assign

> or tag on feelings of ownership/attachment

> to an e-book as they do to a print.

Perhaps readers of e_books will base these feelings of attachment or value on different yardsticks. It could be annotations made on an e-book by various readers or peers that the new reader comes across that piques his/her interests. Or owning a live book. Imagine a p_book with an rss feed that keeps updating itself. With a history option, you could track the changes int he book’s life.

I can imagine holographic books that are connected to servers being in my holograph shelf. Each time I ‘open’ a h_book, I’ll find new comments/annotations. That would be my way of ‘bookmarking’/keeping books I enjoy or am interested in and keeping up with new views. This i feel, is close to keeping a p_book.

-sgsy