ebr is back after a several month hiatus during which time it was overhauled. The site, published by AltX was among the first places where the “technorati meets the literati” and I always found it attractive for its emphasis on sustained analysis of digital artifacts and the occasional pop culture reference. The latest project, first person series, seems to answer a lot of what bob finds attractive in the blogs of juan cole and others. And although I’ve heard ebr called “too linear” (as compared to Vectors, USC’s e-journal) the interface goes a long way toward solving the problem of the scrolling feature of many sites/blogs which privilege what’s new. The interweaving threads with search capabilities seem quite hearty.

Monthly Archives: November 2005

pages á la carte

The New York Times reports on programs being developed by both Amazon and Google that would allow readers to purchase online access to specific sections of books — say, a single recipe from a cookbook, an individual chapter from a how-to manual, or a particular short story or poem from an anthology. Such a system would effectively “unbind” books into modular units that consumers patch into their online reading, just as iTunes blew apart the integrity of the album and made digital music all about playlists. We become scrapbook artists.

It seems Random House is in on this too, developing a micropayment model and consulting closely with the two internet giants. Pages would sell for anywhere between five and 25 cents each.

google print’s not-so-public domain

Google’s first batch of public domain book scans is now online, representing a smattering of classics and curiosities from the collections of libraries participating in Google Print. Essentially snapshots of books, they’re not particularly comfortable to read, but they are keyword-searchable and, since no copyright applies, fully accessible.

Google’s first batch of public domain book scans is now online, representing a smattering of classics and curiosities from the collections of libraries participating in Google Print. Essentially snapshots of books, they’re not particularly comfortable to read, but they are keyword-searchable and, since no copyright applies, fully accessible.

The problem is, there really isn’t all that much there. Google’s gotten a lot of bad press for its supposedly cavalier attitude toward copyright, but spend a few minutes browsing Google Print and you’ll see just how publisher-centric the whole affair is. The idea of a text being in the public domain really doesn’t amount to much if you’re only talking about antique manuscripts, and these are the only books that they’ve made fully accessible. Daisy Miller‘s copyright expired long ago but, with the exception of Harvard’s illustrated 1892 copy, all the available scanned editions are owned by modern publishers and are therefore only snippeted. This is not an online library, it’s a marketing program. Google Print will undeniably have its uses, but we shouldn’t confuse it with a library.

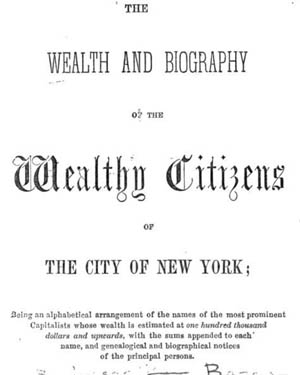

(An interesting offering from the stacks of the New York Public Library is this mid-19th century biographic registry of the wealthy burghers of New York: “Capitalists whose wealth is estimated at one hundred thousand dollars and upwards…”)

electronic literature collection – call for works

The Electronic Literature Organization seeks submissions for the first Electronic Literature Collection. We invite the submission of literary works that take advantage of the capabilities and contexts provided by the computer. Works will be accepted until January 31, 2006. Up to three works per author will be considered.

The Electronic Literature Collection will be an annual publication of current and older electronic literature in a form suitable for individual, public library, and classroom use. The publication will be made available both online, where it will be available for download for free, and as a packaged, cross-platform CD-ROM, in a case appropriate for library processing, marking, and distribution. The contents of the Collection will be offered under a Creative Commons license so that libraries and educational institutions will be allowed to duplicate and install works and individuals will be free to share the disc with others.

The editorial collective for the first volume of the Electronic Literature Collection, to be published in 2006, is:

N. Katherine Hayles

Nick Montfort

Scott Rettberg

Stephanie Strickland

Go here for full submission guidelines.

wikipedia hard copy

Believe it or not, they’re printing out Wikipedia, or rather, sections of it. Books for the developing world. Funny that just days ago Gary remarked:

“A Better Wikipedia will require a print version…. A print version would, for better or worse, establish Wikipedia as a cosmology of information and as a work presenting a state of knowledge.”

Prescient.

the creeping (digital) death of fair use

Meant to post about this last week but it got lost in the shuffle… In case anyone missed it, Tarleton Gillespie of Cornell has published a good piece in Inside Higher Ed about how sneaky settings in course management software are effectively eating away at fair use rights in the academy. Public debate tends to focus on the music and movie industries and the ever more fiendish anti-piracy restrictions they build into their products (the latest being the horrendous “analog hole”). But a similar thing is going on in education and it is decidely under-discussed.

Gillespie draws our attention to the “Copyright Permissions Building Block,” a new add-on for the Blackboard course management platform that automatically obtains copyright clearances for any materials a teacher puts into the system. It’s billed as a time-saver, a friendly chauffeur to guide you through the confounding back alleys of copyright.

But is it necessary? Gillespie, for one, is concerned that this streamlining mechanism encourages permission-seeking that isn’t really required, that teachers should just invoke fair use. To be sure, a good many instructors never bother with permissions anyway, but if they stop to think about it, they probably feel that they are doing something wrong. Blackboard, by sneakily making permissions-seeking the default, plays to this misplaced guilt, lulling teachers away from awareness of their essential rights. It’s a disturbing trend, since a right not sufficiently excercised is likely to wither away.

Fair use is what oxygenates the bloodstream of education, allowing ideas to be ideas, not commodities. Universities, and their primary fair use organs, libraries, shouldn’t be subjected to the same extortionist policies of the mainstream copyright regime, which, like some corrupt local construction authority, requires dozens of permits to set up a simple grocery store. Fair use was written explicitly into law in 1976 to guarantee protection. But the market tends to find a way, and code is its latest, and most insidious, weapon.

Amazingly, few academics are speaking out. John Holbo, writing on The Valve, wonders:

Why aren’t academics – in the humanities in particular – more exercised by recent developments in copyright law? Specifically, why aren’t they outraged by the prospect of indefinite copyright extension?…

…It seems to me odd, not because overextended copyright is the most pressing issue in 2005 but because it seems like a social/cultural/political/economic issue that recommends itself as well suited to be taken up by academics – starting with the fact that it is right here on their professional doorstep…

Most obviously on the doorstep is Google, currently mired in legal unpleasantness for its book-scanning ambitions and the controversial interpretation of fair use that undergirds them. Why aren’t the universities making a clearer statement about this? In defense? In concern? Soon, when search engines move in earnest into video and sound, the shit will really hit the fan. The academy should be preparing for this, staking out ground for the healthy development of multimedia scholarship and literature that necessitates quotation from other “texts” such as film, television and music, and for which these searchable archives will be an essential resource.

Fair use seems to be shrinking at just the moment it should be expanding, yet few are speaking out.