Etymology: Latin rhapsodia, from Greek rhapsoidia recitation of selections from epic poetry, rhapsody, from rhapsoidos rhapsodist, from rhaptein to sew, stitch together – Merriam-Webster OnLine

The BBC is moving into web services, allowing the public to build applications that repurpose BBC content.

See also:

“your news, your pictures”

“find it rip it mix it share it”

Monthly Archives: May 2005

the blog and the book

A couple of interesting experiments going on with blogs and books..

Dave Munger is taking the blog on a test drive as an ebook reader, putting together what he calls a “blook.” To show he means business, he’s chosen Moby Dick as the pilot text (but before starting, he’s working out formatting issues with Melville’s short story Bartleby, the Scrivener). I’m intrigued by the idea of using the blog form to generate discussion of a text – breaking it up into serial posts, jotting notes and analysis in the comment stream. It could make for a nice communal reading experience, as in a lit class, or virtual book club. It’s a game: drop the book in the blog and it ripples; different subjective worlds (of the readers) converge and collide. It’s very suggestive to combine this most conversational of media with the frozen, linear novel. For solitary reading, however, I’m not convinced that this would be a useful format.

Spark Armada, a “digital lifestyle, social software, creativity and science fiction conversation hub” in Israel, recently kicked off the “Keyboard” project, inviting bloggers to post stories on their sites that will be considered for inclusion in a print anthology. The idea seems to be to use the blogosphere’s mode of interwoven conversation as a way to generate creative work. The endpoint may be a conventional printed object, but Keyboard is interested in taking a different route in getting there.

could this be a textbook?

![]() Aural learning. Podcasting your reading assignment. New powers for students to time-shift materials and work. Load up chapter five on your iPod and take it to go.

Aural learning. Podcasting your reading assignment. New powers for students to time-shift materials and work. Load up chapter five on your iPod and take it to go.

Dyslexia’s defeat?

Publishers must be noticing all the earbuds in students’ ears.. how can they make some noise in that space?

But how do you take notes, make annotations on audio? How do you evaluate learning? Could this be anything more than a supplement?

sharing teachers, connecting classrooms

An initiative in Maine is using technology to provide advanced placement programming to high school students in rural areas. The Maine Distance Learning Project “identifies Maine teachers and schools that are interested in offering Advanced Placement programming to be delivered over distance to students in Maine via the state-wide ATM network during the 2005/2006 school year.”

According to a recent article in Newsweek, Reaching Rural Students, support was provided by the University of Maine. The University set up “a network of cameras in AP classes like Brendan Murphy’s calculus and statistics class. These classes were broadcast to five other schools across the state. 90 other schools have a set up like Carrabec’s. Each site’s classroom has a three-foot television screen split into quadrants, and two cameras in each room.”

valuing nonmarket production

As the mother of a toddler, I’m keenly aware of how grueling the 24/7 unpaid work of parenthood really is. A friend of mine sent around a mother’s day email that added up all the little things we do and arrived at a salary of about $131,000. Slave wages compared to the figure in Jennifer Steinhauer’s Times article, The Economic Unit Called Supermom which came up with “an estimated $707,126 annual paycheck.”

Problem is, no one will ever pay me $700K to do what I do for free. So is there any point in speculating about the market value of mothering? Perhaps there is. Steinhauer tells us that In 2003, the Bureau of Labor Statistics conducted its first-ever Time Use Survey, which examined the doings of 21,000 Americans over a 24-hour period. “There were a number of economists who were interested in valuing nonmarket production,” said Diane Herz, the survey’s project manager.

Many social scientists have explored the “social capital” gained by participating in these otherwise uncompensated activities. Social scientists argue, for example, that test scores go up in schools where parent volunteerism is highest, and that crime is reduced in communities with high civic participation. “Social capital is usually defined as the networks and relationships we have, as well as the trust and sense of mutuality that arise from them,” said Amy Caiazza, a study director working with Ms. Hartmann.

So this got me thinking about digital networks and I started wondering how much web content is created, nurtured and maintained without compensation. And how apropos the term “nonmarket production” is for most web activity. The networked book, for example, relies on free contributions and other forms of non-commercial support. What does this mean for the future of books? Does the web have the potential to turn the book industry into an unpaid labor of love?

publishing bigwig fears change

From Sunday’s Observer: “Oh no, it’s the death of the book … again”. Robert McCrum pokes fun at Nigel Newton, CEO and co-founder of Bloomsbury, British publisher of the Harry Potter books, for remarks on what he calls the “Napsterisation” of publishing – i.e. digitization – and the threat it poses to “the cultural and intellectual tradition of the past 600 years.”

McCrum rejoins: “Before we allow Mr Newton and the merchants of doom to seize control of our cultural imaginations, it’s worth recalling that Gutenberg was a vital part of the Renaissance. Gutenberg and our own Caxton were eventually followed by Shakespeare, Marlowe and Milton.

“Delivery systems evolve. Instead of whingeing about Google, we could celebrate the extraordinary technology that will bring a cornucopia of hitherto inaccessible material before a bigger international audience than ever before.”

island hopping – a new paradigm for web search

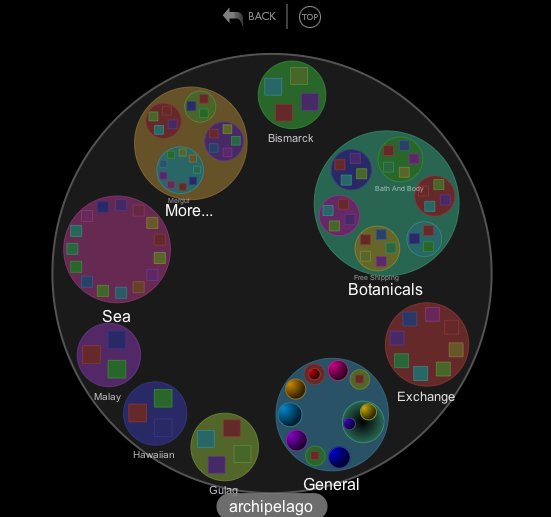

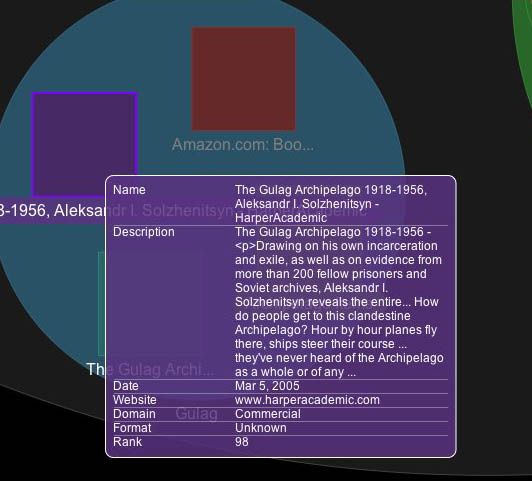

When you search the web on Google or Yahoo, your results come up in a stack – a long scroll unfurling at your feet. Ranking is what makes the whole thing work – the most relevant, or most linked-to, items are placed near the top, and more often than not, you get what you’re looking for. Few really bother to sort through the rest of the pile, even though valuable stuff could be buried there (and what if you don’t know exactly what you’re looking for?). Clustered search takes a different appproach, breaking up results into useful categories and themes, enabling users to penetrate the stack more quickly (see Clusty, or its parent Vivisimo). It’s an interesting compromise with top-down shelf-based hierarchies. Clustered search doesn’t impose categories on you from the get-go, rather, it applies them as needed – building shelves on the fly. Grokker, a Yahoo-powered “visual” search engine, takes it a step further, arranging clusters into archipelagos of information, “giving you the ability to explore any subject far beyond the obvious.” Each category is represented by a circle, containing site links (appearing as squares) or smaller circles (subcategories). Above is my archipelago for… “archipelago.” It brings up top level clusters for “botanicals” (Archipelago Botanicals produces a popular line of soaps, lotions and scented candles), “Hawaiian,” “Sea,” “Gulag,” and others. Drag over a site and a nice summary pops up (see righthand image above) – much more readable than the hodge podge you get in Google.

Link to NY Times article on Grokker.

Story about Vivisimo clustering search tool built specially for navigating the massive EU constitution.

lost recording of Douglas Adams, and, Flash in the pan

Douglas Adams recorded this (slightly hyperbolic) audio piece back in 1993 to promote the Voyager Expanded Books series. On “getting the book invented”:

I recently saw the new Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy movie, which features as one of its central characters a very powerful electronic book – a guide to “life, the universe and everything.” Coming away, I felt a bit uneasy. Could this be the future of the book in the age of Adobe-Macromedia? As portrayed in the film, the Guide is essentially a compendium of Flash animations, with a little bit of text, and a wry British voiceover. Granted, it’s just a narrative device in a film, designed more for style than for content. But is this any less true in real life?.. with all these websites built in Flash, and all the Flash-enhanced garbage on television – especially in ads and sports coverage (notice how TV’s become a lot more like a video game?). The same goes for the film. Though chock-a-block with spiffy visual effects, and flavored with Douglas Adams’ unmistakable wit, it’s basically all style, all pose – visual fireworks for a passive viewer. We have only just started to explore the frontier of media-rich, networked books. But if “FlashAcrobat” becomes the writing tool of choice, that just might end up preempting any serious consideration of an active, critical role for the reader. Books become the half time show at the Super Bowl. Flash frenzy…

I recently saw the new Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy movie, which features as one of its central characters a very powerful electronic book – a guide to “life, the universe and everything.” Coming away, I felt a bit uneasy. Could this be the future of the book in the age of Adobe-Macromedia? As portrayed in the film, the Guide is essentially a compendium of Flash animations, with a little bit of text, and a wry British voiceover. Granted, it’s just a narrative device in a film, designed more for style than for content. But is this any less true in real life?.. with all these websites built in Flash, and all the Flash-enhanced garbage on television – especially in ads and sports coverage (notice how TV’s become a lot more like a video game?). The same goes for the film. Though chock-a-block with spiffy visual effects, and flavored with Douglas Adams’ unmistakable wit, it’s basically all style, all pose – visual fireworks for a passive viewer. We have only just started to explore the frontier of media-rich, networked books. But if “FlashAcrobat” becomes the writing tool of choice, that just might end up preempting any serious consideration of an active, critical role for the reader. Books become the half time show at the Super Bowl. Flash frenzy…

Paul Boutin, writing last week in Slate, makes draws a more encouraging parallel to the fictional Guide: Wikipedia. “..a real-life Hitchhiker’s Guide: huge, nerdy, and imprecise.” I had not been aware that Adams, before his untimely death in 2001, had experimented with his own web version of the Guide, a sort of proto-Wikipedia called h2g2, hosted by the BBC. Flipping through just a few of the articles, it’s interesting to see a collaborative work sustaining a unified authorial voice. The tone, not to mention the choice of subjects, comes across as unmistakably Adams – the ur-author – even though the guide was built by diverse contributors, in more or less the same fashion as Wikipedia. Here’s the intro paragraph from the article “The Problem with Driving Directions”:

“In the absence of in-car electronic route maps, driving directions are sets of instructions given to drivers in order for them to reach their desired destination. These basically come in two different forms: oral and written. Whether oral or written, they are widely used due to the fact that people often have no idea how to get to where they are going, and naturally assume that they are the only ones that do not know, and so ask someone else. Unfortunately, this other person tends not to know either.”

Building on Boutin’s comparison, you could argue that Wikipedia is simply imitating the tone and format of a paper encyclopedia, much as Adams’ followers in h2g2 are emulating the style of his novels. As a reference tool, Wikipedia may have far outstripped Adams’ project, but questions of accuracy and reliability persist. h2g2, on the other hand, sits much more comfortably in its skin, cheerfully acknowledging that it contains “many omissions,” and “much that is apocryphal, or at least wildly inaccurate.” A much more serious and important endeavor, Wikipedia is still wrestling with the anxiety of influence exerted by its forebear, the encyclopedia. Over time, will its voice change?

Europe aims canon at Google

Google is riding high. With nearly 50 percent market share, it is the most widely used search engine on the web. It is even beginning to act suspiciously like a portal (notice the “login” link tucked discretely in the upper right corner?), handling your mail, hosting your blog, helping you find files on your desktop, and even storing a history of all your web searches. (No doubt, Google’s expansion into web-based applications has Microsoft scared – they’ve always considered software their turf.) Google recently patented a system that ranks news searches by the quality and credibility of the source. Gorgeous satellite maps have put the surface of the earth in our web browser and left people breathless (see the Google Sightseeing blog, or the memorymap tag on Flickr as examples of sheer exultation in seeing the world through Google maps). Late last year, Google announced plans to digitize and put online major portions of the libraries of Stanford, U. Michigan, Harvard, Oxford and the NY Public Library. And on top of all this, its stock has continued to soar. Already this year, the newly public company shattered predictions, earning $369.1 million in the first quarter alone, more than covering the cost of the projected 10-year library scanning project. It seems there is no limit to what Google might do.

That is precisely what has Europeans so worried. Across the Atlantic, Google is coming to be seen as yet another symbol of American cultural hegemony, bestriding the web like a colossus. And the library project touches a particularly sensitive nerve, raising questions of cultural heritage – and cultural destiny. If the future of libraries is solely in Google’s hands, what will be left out in the process? Will English become the lingua franca not only for politics and commerce, but for all intellectual discourse? Not content simply to ask questions, Europe has responded. In February, Jean-Noel Jeanneney, chief librarian of the Bibliothè que Nationale de France, warned that Google Print would effectively anglicize the world’s knowledge, and called for a French digitization effort to beat back the surging english tide. Less than a month later, President Jacques Chirac gave Jeanneney’s proposal the green light. Then, last week, nineteen national libraries, evidently moved by France’s determination, signed a joint motion urging the creation of a giant pan-European digital library to counterbalance the nascent Googlian stacks. A couple days ago, 16 EU culture ministers, several heads of state, and over 800 artists and intellectuals met in Paris to close the deal, issuing a strong, continent-wide directive to preserve and promote culture, beginning with the digitization of European library collections.

That is precisely what has Europeans so worried. Across the Atlantic, Google is coming to be seen as yet another symbol of American cultural hegemony, bestriding the web like a colossus. And the library project touches a particularly sensitive nerve, raising questions of cultural heritage – and cultural destiny. If the future of libraries is solely in Google’s hands, what will be left out in the process? Will English become the lingua franca not only for politics and commerce, but for all intellectual discourse? Not content simply to ask questions, Europe has responded. In February, Jean-Noel Jeanneney, chief librarian of the Bibliothè que Nationale de France, warned that Google Print would effectively anglicize the world’s knowledge, and called for a French digitization effort to beat back the surging english tide. Less than a month later, President Jacques Chirac gave Jeanneney’s proposal the green light. Then, last week, nineteen national libraries, evidently moved by France’s determination, signed a joint motion urging the creation of a giant pan-European digital library to counterbalance the nascent Googlian stacks. A couple days ago, 16 EU culture ministers, several heads of state, and over 800 artists and intellectuals met in Paris to close the deal, issuing a strong, continent-wide directive to preserve and promote culture, beginning with the digitization of European library collections.

More serious digitization projects are undoubtedly a good thing. The European effort, being a more purely civic enterprise, might in fact turn out far better than Google Print, which clearly has a large commercial dimension (deals with publishers, advertising etc.). The Euro initiative might produce bona fide electronic editions, not just searchable scans – fully structured, annotated and perhaps employing other scholarly resources (but let’s not hold our breath). To be fair, Google has never said it wants to be the only gig in town. Rather, they hope to act as a catalyst for other digitization efforts. And judging by Europe’s reaction, it seems to be working. Looking at this latest transatlantic folly, it’s funny to think of the Bush administration trying to undercut European unity, splitting the continent into “old” and “new” in the hope of fishing out support for the Iraq war. We’ve seen where that kind of destructive diplomacy has led us. But quite wonderfully, Google appears to have achieved the opposite, galvanizing a united Europe with a big, visionary idea. If the Euro library project exists for no other reason than the perceived imperialism of Google, then so be it. It will result in a great gift for all. If only our foreign policy were so deft.

(image by libraryman via Flickr)

tagging the digital city: a new way to make your mark

Remember subway trains in the 70’s & 80’s; traversing the conduits of New York City’s tunnels bearing the spray-painted “tags” of urban graffiti artists? Taggers, as you may recall, were interested in trafficking their name on high visibility real estate like bridges, tunnels, buildings, landmarks, and subway cars. They were individuals attempting to mark the complex urban landscape in an effort to be “seen.” I think this is the motivation behind the re-emergence of tagging in the context of the internet landscape, which is becoming increasingly cluttered and noisy in the same way that cities are. Tagging is a way to stand out and be seen, it is a way to connect, it is a way to make your contribution last a little longer and go a little further. The fact that these “tags” are useful for organizing things is something of a happy accident. People tag because they want other people to see their work. Because they want digital objects to bear their mark. This is a very human thing. Can we use it to help us organize everything? Maybe. An interesting article in CNN, ‘Tagging’ helps unclutter data: Online search categorizes how humans label things, posted Tuesday, May 3, 2005 gives a good overview of how tagging and social software are being used to organize data. But it also points out the possible drawbacks to this method of organization.

When we think of subway graffiti, we think of the elaborate, colorful calligraphy that ended up in art galleries and coffee table books. I include a picture (above) by Magnum Photographer Bruce Davidson, to remind you that most of it was uncreative and relatively ugly black marker work. Worse case scenario, spammers figure out how to exploit metadata, proliferating their “tags.” Scrawling their signature on every digital object they can access, and doing for the digital landscape what the spray can did for 1980’s New York.