Some more thoughts on Clay Shirky‘s keynote lecture on “folksonomies” at the Interactive Multimedia Culture Expo this past weekend in New York (see earlier post, “as u like it – a networked bibliography“).

Shirky talks about the classification systems of libraries – think card catalogues. Each card provides taxonomical directions for locating a book on a library’s shelves. And like shelves, the taxonomies are rigid, hierarchical – “cleaving nature at the joints,” in his words. The rigidity of the shelf tends to fossilize cultural biases, and makes it difficult to adjust to changing political realities. The Library of Congress, for instance, devotes the same taxonomic space to the history of Switzerland and the Balkan Peninsula as it does to the history of all Africa and Asia. See the table below (source: Wikipedia).

Or take the end of the Cold War.. When the Soviet Union disintegrated, the world re-arranged itself. An old order was smashed. Dozens of political and cultural identities poured out of stasis. Imagine the re-shelving effort that was required! Librarians shuddered, knowing this was a task that far exceeded their physical and temporal resources. And so they opted to keep the books where they were, changing the section’s header to “the former Soviet Union.” Problem solved. Well, sort of.

When communication and transportation were slower, libraries had a chance of keeping up with the world. But the management of humanity’s paper memory has become too cumbersome and complex – too heavy – to register every nuance, shock, and twist of history and human thought. Now, with the web becoming our library, there is, quoting Shirky again, “no shelf,” and it’s possible to have more fluid, more flexible ways of classifying knowledge. But the web has been slow to realize this. Look at Yahoo!, which, since first appearing on the scene, has organized its content under dozens of categories, imposing the old shelf-based model. As a result, their home page is the very picture of information overload. Google, on the other hand, decided not to impose these hierarchies, hence their famously spartan portal. Given the speed and frequency with which we can document every moment of our lives in every corner of the world, in every conceivable media – and considering that this will only continue to increase – there is no way that the job of organizing it all can be left solely to professional classifiers. Shirky puts it succinctly: “the only group that can organize everything is everybody.”

That’s where folksonomy comes in – user-generated taxonomy built with metadata, such as tags. Everybody can apply tags that reflect their sense of how things should be organized – their own personal Dewey Decimal System. There is no “top level.” There are no folders. There is no shelf. Categories can overlap endlessly, like a sea of Venn diagrams. The question is, how do we prevent things from becoming incoherent? If there are as many classifications as there are footsteps through the world, then knowledge ceases to be a tool we can use. And though folksonomy frees us from the rigid, top-down hierarchies of the shelf, it subjects us to the brutal hierarchy of the web, which is time.

The web tends to privilege content that is new or recently updated. And tagging systems, in their present stage of development, are no different. Like blogs, tag searches place new content at the top, while the old stuff gets swiftly buried. As of this writing, there are nearly 24,000 photos on Flickr tagged with “China” (and this with Flickr barely a year old). You get the recent uploads first and must dig for anything older. Sure, you can run advanced searches on multiple tags to narrow the field, but how can you be sure you’ve entered the right tags to find everything that you’re looking for? With Flickr, it is by and large the photographers themselves that apply the tags, so we have to be mind readers to guess the more nuanced classifications. Clearly, we’ll need better tools if this is all going to work. Far from becoming obsolete, librarians may in fact become the most important people of all. It’s not difficult to imagine their role shifting from the management of paper archives to the management of tags. They are, after all, the original masters of metadata. Different schools of tagging could emerge and we would subscribe to the ones we most trust, or that mesh best with our own view of things. Librarians could become the sages of the web.

It’s easy to get preoccupied with the volume of information we’re dealing with today. But the issue of time, which I raised earlier, should also be foremost in our minds. If libraries were to shake as violently and often as the world, they would crumble. They are not newsrooms. They are not bazaars. Like writing, libraries create stable, legible forms out of swirling passions. They provide refuge. Their cool, peaceful depths enable analysis and abstraction. They provide an environment in which the world can appear at a distance, spread out on literate strands that may be read in calm and quiet. As a library, the web feels more like the real world – sometimes too much so. It throbs with life, with momentary desires, with sudden outbursts. It is hypersensitive to change. But things pile up, or vanish altogether. I may have the smartest, most intuitive tags in the world, but in a year they might become nothing more than headstones for dead links. It is ironic that with greater access to more knowledge than ever before, we tend to live in a perpetual present. If folksonomies are truly where we’re headed, then we must find ways to overcome the awful forgetfulness of the web. Otherwise, we may regret leaving the old, stubborn, but dependable shelf behind.

The

The

Something to watch is how folksonomies are converging with social software platforms like

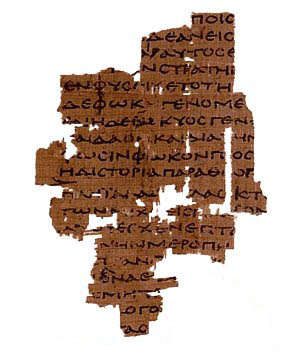

Something to watch is how folksonomies are converging with social software platforms like  “Once it had walls three miles round, with five or more gates; colonnaded streets, each a mile long, crossing in a central square; a theatre with seating for eleven thousand people; a grand temple of Serapis. On the east were quays; on the west, the road led up to the desert and the camel-routes to the Oases and to Libya. All around lay small farms and orchards, irrigated by the annual flood — and between country and town, a circle of dumps where the rubbish piled up.” (from

“Once it had walls three miles round, with five or more gates; colonnaded streets, each a mile long, crossing in a central square; a theatre with seating for eleven thousand people; a grand temple of Serapis. On the east were quays; on the west, the road led up to the desert and the camel-routes to the Oases and to Libya. All around lay small farms and orchards, irrigated by the annual flood — and between country and town, a circle of dumps where the rubbish piled up.” (from

Even before the head of the University of Nebraska library began bemoaning how the pictures had fallen out of their collection of vintage agronomy ebooks, the

Even before the head of the University of Nebraska library began bemoaning how the pictures had fallen out of their collection of vintage agronomy ebooks, the