“Once it had walls three miles round, with five or more gates; colonnaded streets, each a mile long, crossing in a central square; a theatre with seating for eleven thousand people; a grand temple of Serapis. On the east were quays; on the west, the road led up to the desert and the camel-routes to the Oases and to Libya. All around lay small farms and orchards, irrigated by the annual flood — and between country and town, a circle of dumps where the rubbish piled up.” (from Waste Paper City by P.J. Parsons)

“Once it had walls three miles round, with five or more gates; colonnaded streets, each a mile long, crossing in a central square; a theatre with seating for eleven thousand people; a grand temple of Serapis. On the east were quays; on the west, the road led up to the desert and the camel-routes to the Oases and to Libya. All around lay small farms and orchards, irrigated by the annual flood — and between country and town, a circle of dumps where the rubbish piled up.” (from Waste Paper City by P.J. Parsons)

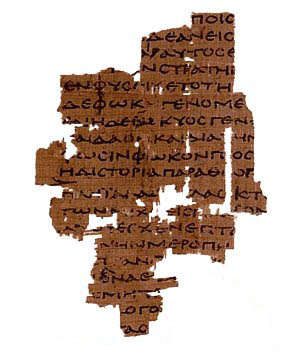

It was in this garbage dump, outside the ancient city of Oxyrhynchus in modern-day Egypt, vanished except for a single column, that 400,000 classical manuscript fragments were unearthed by British archaeologists in the late 19th century. It has long been thought that the texts, which reside at Oxford’s Sackler Library, represent a vast number of missing pieces from the known classical canon, in addition to thousands of humdrum documents – petitions, land deeds, wage receipts, orders for arrest, registration of slaves and goats etc. – shedding light on daily life in the Greco-Roman world. The problem is that they are largely unreadable, crushed and mashed together, blackened by years of decay, nibbled by worms. Here and there over the years, individual texts have been deciphered, making waves through the academic world. But now, the Oxyrhynchus Papyri can at last be decoded en masse through the use of multi-spectral imaging, a technique developed in satellite photography, which teases texts to the surface with infra-red light. Hailing it as the “holy grail” of antiquarian discoveries, classicists are predicting a major wave of restoration to the received literary canon, including lost plays of Sophocles and Euripides, a post-Homeric epic by Archilochos, and even missing gospels of the New Testament.

Read article in the Independent, via Grand Text Auto.

if:book

A Project of the Institute for the Future of the Book