Between now and March 29, when oral arguments begin before the Supreme Court in MGM v. Grokster, the Electronic Frontier Foundation is assembling a list, one invention per day, of technologies that could be considered illegal if the movie and music industries prevail in redefining the scope of permissable copying. Email, blogs, VCRs, and xerox machines are among the gadgets listed so far.

![]() “Ever since the Betamax ruling in 1984, inventors have been free to create new copying technologies as long as they are capable of substantial noninfringing (legal) uses. But by the end of this year, all that could change. In MGM v. Grokster, Hollywood and the recording industry are asking for the power to sue out of existence any technology that appears to be a threat, even if it passes the Betamax test. That puts at risk any copying technology that Betamax currently protects as well as any new technologies Hollywood doesn’t like.

“Ever since the Betamax ruling in 1984, inventors have been free to create new copying technologies as long as they are capable of substantial noninfringing (legal) uses. But by the end of this year, all that could change. In MGM v. Grokster, Hollywood and the recording industry are asking for the power to sue out of existence any technology that appears to be a threat, even if it passes the Betamax test. That puts at risk any copying technology that Betamax currently protects as well as any new technologies Hollywood doesn’t like.

“To raise awareness about what’s at stake in the Grokster case, EFF is profiling one Betamax-protected gadget every weekday until the oral arguments before the Supreme Court on March 29. Some of these examples are in fun, some more serious, but all represent general-purpose technologies that can be used for both infringing and noninfringing purposes. Check them out and pass the word along.”

(via Boing Boing)

Monthly Archives: March 2005

baking google’s cookies

![]() Bibliotheke points to the recent adventures of Greg Duffy, a talented Texas college student who figured out how to read entire copyrighted books in Google Print by “baking” the cookies (data sent from to your computer from a web browser to store preferences for specific sites and pages) Google uses to impose search limits on protected material. Duffy took on the challenge largely out of curiousity, but doesn’t deny that he fantasizes about his chutzpah landing him a job at Google. He hasn’t been hired yet, but he did manage to attract a great deal of attention and over 10,000 hits to his site from more than 60 countries. And in the sudden commotion, he mysteriously disappeared from Google’s web search results, only to reappear shorly after Google Print had been fixed to repel the hack. Any connection between the two events was cheerily denied by a Google representative writing in the comments on Duffy’s blog under the nom de plume “Google Guy.” Conspiracy theories abound, but Duffy has retained an excellent sense of humor throughout the whole affair, and still makes no secret of his hopes that sheer audacity and display of chops might yet get him hired by the juggernaut he so admires and loves to tease.

Bibliotheke points to the recent adventures of Greg Duffy, a talented Texas college student who figured out how to read entire copyrighted books in Google Print by “baking” the cookies (data sent from to your computer from a web browser to store preferences for specific sites and pages) Google uses to impose search limits on protected material. Duffy took on the challenge largely out of curiousity, but doesn’t deny that he fantasizes about his chutzpah landing him a job at Google. He hasn’t been hired yet, but he did manage to attract a great deal of attention and over 10,000 hits to his site from more than 60 countries. And in the sudden commotion, he mysteriously disappeared from Google’s web search results, only to reappear shorly after Google Print had been fixed to repel the hack. Any connection between the two events was cheerily denied by a Google representative writing in the comments on Duffy’s blog under the nom de plume “Google Guy.” Conspiracy theories abound, but Duffy has retained an excellent sense of humor throughout the whole affair, and still makes no secret of his hopes that sheer audacity and display of chops might yet get him hired by the juggernaut he so admires and loves to tease.

It’s a bit tech-heavy, but it’s worth reading his post and the updates that follow, if for no other reason than for his amusing riff on the cookie motif.

“So recently I wrote some software to grab and store up a bunch of cookies, keep them for more than 24 hours, and then automate searching for pages by this method. If I wanted to view page 100, the software would search for it and attempt to extract the image with a regular expression. If that doesn’t work, it will search for page 99 and extract the “next page” link to get to page 100. It will continue doing this for page 101, 98, and 102 until it finds the correct page. Whenever a cookie would hit the hard limit, I’d replace it with a new cookie from the queue. By grabbing the “next” and “previous” links automatically in this “inductive” fashion and using the search for skipping, I could view an entire book on Google Print with one click every time. I later modified the software to spit out a PDF of the book. I used simple components like GoogleCookie (cookie with accessible properties), GoogleCookieOven (queue with “baking time”, i.e. it only pops when the head of the queue is old enough to get the ability to search), and GoogleCookieBaker (thread that keeps the oven full of baking cookies by querying Google for new ones when the number drops below a certain threshold).”

graphic novel as illuminated manuscript

The institute is hosting a competition called Born Digital 1: Illumination, which asks artists, writers, programmers, and designers to address the conceptual underpinnings of illuminated manuscripts in the context of the born digital artifact. We are playing somewhat loose with the term “illuminated manuscript.” Our “Born Digital” contest asks for a single page rather than an entire book and is not necessarily interested in a literal reinvention of the form (unless you’ve come up with a particularly great one). We are intrigued by the fact that illuminated manuscripts do not separate text and image into different disciplines requiring separate platforms for display and critical discourse. We find that, in the workshop of the digital medium, disciplinary amalgams are once again emerging, and we would like to examine this shift.

Without attempting to give a history of the evolution of this form, I will, over the next several days, point out a few contemporary models that pay tribute to medieval illumination. The graphic novel comes immediately to mind. Chris Ware’s, “Jimmy Corrigan the Smartest Kid on Earth, Art Spiegelman’s, “Maus,” and David B’s, “This Sweet Sickness,” have shown us the power of image and text working in tandem to deliver a profound aesthetic, emotional, and intellectual experience.

Early digital versions of the graphic novel include Pyramids of Mars, which was published in 1997 by Richard Douglas and Geoffrey Holmes, and claims to be the first downloadable digital graphic novel. And Scott Frazier’s TRANSCENDENCE which the author describes as: partially animated, partially illustrated and partially text. It will, hopefully, stretch the bounds of multimedia and become something new, more than a mere fusion of comic and animation.

![]() And thanks to friend Douglas Wolk, the absolute authority on graphic novels (and one of the smartest and nicest guys I know) for the following recommendations: “Patrick Farley’s, “The Spiders,” is wonderful and uses the medium nicely. Dylan Meconis’s, “Bite Me” is pretty much just scanned images, but she serialized the whole thing online, and she’s like 19 years old and super-fun.”

And thanks to friend Douglas Wolk, the absolute authority on graphic novels (and one of the smartest and nicest guys I know) for the following recommendations: “Patrick Farley’s, “The Spiders,” is wonderful and uses the medium nicely. Dylan Meconis’s, “Bite Me” is pretty much just scanned images, but she serialized the whole thing online, and she’s like 19 years old and super-fun.”

I hope this serves as a useful beginning for discussion on graphic novel as illuminated manuscript. I’m relying on readers to help me flesh the idea out.

polish poet pens for phone

![]() The Digital Museum of Modern Art, a virtual exhibition space, is featuring “Czolgaj Sie” (“Crawl”), verses by Polish poet Marcin Swietlicki, illustrated by fellow countryman Cezary Ostrowski. The poem is exhibited on the museum’s website, and has also been optimized for reading on a mobile phone.

The Digital Museum of Modern Art, a virtual exhibition space, is featuring “Czolgaj Sie” (“Crawl”), verses by Polish poet Marcin Swietlicki, illustrated by fellow countryman Cezary Ostrowski. The poem is exhibited on the museum’s website, and has also been optimized for reading on a mobile phone.

I’m not crazy about the poem, but it’s an intriguing experiment. Is there a Flash plugin for phones so one can view dynamic text (like this)?

(via textually)

franco-googlian wars continue…

“…news agency Agence France Press (AFP) is claiming damages of at least $17.5 million and a court order barring Google News from displaying AFP photographs, news headlines or story leads…” (story)

This recalls Virginia’s post a couple months back on “the future of the news.” Will news aggregators and headline-scouring robots be accused of copyright infringement? Will other news providers follow AFP’s lead?

(via Searchblog)

what books should do

earlymoderntexts.com is a project of a retired college professor that aims to present works of early modern thinkers (Descartes, Kant, Hume, etc) in language that can be understood by students. Jonathan Bennett, the creator of the site, recognized that the students he was teaching couldn’t read texts already in English, so he set to simplifying them, editing them himself. Bennett substituted simple words for ones more complicated, elaborated particularly complicated points, and moved important points into bulleted lists, so they could be easily grasped. He’s put his edited versions of the texts online, so the general public can read them.

This is an interesting use of public-domain texts and a good demonstration of what can be done when information is free of copyright. (Some of the texts, it should be noted, aren’t public domain: John Cottingham’s translation of Descartes’s Meditation on First Philosophy is almost certainly subject to copyright even if Descartes isn’t). Clearly a lot of thought has gone into it: Bennett provides a nice explication of his editing conventions. He uses punctuation to show where in the text he’s made changes, starting from the usual brackets and ellipses.

What I found myself wanting when I made my way through his versions, however, was the original, to compare. Tradurre è tradire say the Italians: to translate is to betray, and I always find myself curious as to exactly how the translators are betraying the original. A facing page translation is useful in poetry: you can look at the original and sound out the original line (if you can pronounce the language) to see how the translated line compares. Certainly I could do roughly the same thing here: open up a browser window to a Gutenberg text of the original while I looked at the PDFs that Bennett provides.

But why should we have to do this? Shouldn’t electronic texts keep copies of their original versions internally? What I want in reading software is a tool that lets me instantly compare versions: if the translator has changed a word, I’d like to be able to press a button and see what the original was. You can kind of do something like this with Microsoft Word’s “track changes” feature. But Word’s a deplorable program for reading, and I don’t want to have to make my way through a forest of red and blue underlined and struck-through text. What I want would be a program that opens a copy of Bennett’s version of Decartes, which is able to flip back to Cottingham’s original translation, and then even further to Descartes’ original French. Why don’t we have programs that make it easy to do this? It shouldn’t be hard to do.

novels on your phone

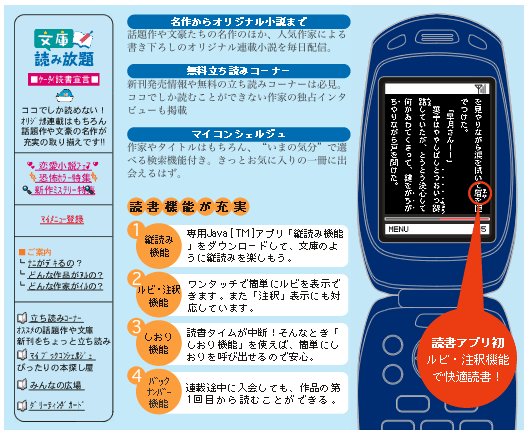

There was a great AP article yesterday on the recent boom in cell phone novels and serials in Japan. The top and bottom images here are pulled from “Bunko Yomihodai,” or “All You Can Read Paperbacks” – a popular microlit site with over 50,000 subscribers, offering 150 titles written or adapted specially for reading on phones.

“In the latest versions, cell-phone novels are downloaded in short installments and run on handsets as Java-based applications. You’re free to browse as though you’re in a bookstore, whether you’re at home, in your office or on a commuter train. A whole library can be tucked away in your cell phone — a gadget you carry around anyway.”

True. Right now, the cell phone is the ultimate indispensable gadget. It’s with us practically all the time. No wonder it’s the first place that electronic books are gaining a foothold.

And the content is varied…

“Surprisingly, people are using cell-phone books to catch up on classics they never finished reading. And people are perusing sex manuals and other books they’re too embarrassed to be caught reading or buying. More common is keeping an electronic dictionary in your phone in case a need arises.”

Microlit hasn’t really taken off here in the States, though there are a few signs that suggest a gradual movement in this direction. There was a bit of buzz about a month ago when Random House acquired a significant minority stake in wireless applications developer VOCEL. And more people seem to be using their phones and PDAs for reading – everything from websurfing, to RSS feeds, to downloaded books (or even raw text files of public domain literature – I tried this on my iPod with this fun hack). But we have yet to see any kind of full-blown lit phenomenon.

The breakthrough work in Japan was a serial called “Deep Love,” the story of a teenage prostitute in Tokyo. It became so popular that it was published as an actual book, and spun off into a TV series, a manga (comics), and a movie. Now the author, named simply Yoshi, is trying his hand at thrillers. From the article:

The breakthrough work in Japan was a serial called “Deep Love,” the story of a teenage prostitute in Tokyo. It became so popular that it was published as an actual book, and spun off into a TV series, a manga (comics), and a movie. Now the author, named simply Yoshi, is trying his hand at thrillers. From the article:“Another work by Yoshi, a horror mystery, has a cell-phone Web link that readers click. One pulls up a video clip of a bleeding face; another shows a letter that tells people to go on living.

“Yoshi, a former prep-school instructor who sees his readers as “a community,” reads the dozens of e-mail messages teenage fans send him daily and uses their material for story ideas.

“He also knows immediately when readers are getting bored and changes the plot when access tallies start dipping for his stories.

“‘It’s like playing live music at a club,'” he said. ‘You know right away if the audience isn’t responding, and you can change what you’re doing right then and there.'”

Remember that Dickens often wrote in this way. Perhaps we are witnessing the return of serialized novels.

50 people see… a networked picture book

![]() This image was created by blending 50 photos in Flickr all tagged with “the gates” (the program was devised by brevity). You can see the complete set of images here. Try guessing the tag for each image – I found that, even though they are quite abstract, there are ghostly traces of shape and line that quietly announce themselves. It sort of whispers to you.

This image was created by blending 50 photos in Flickr all tagged with “the gates” (the program was devised by brevity). You can see the complete set of images here. Try guessing the tag for each image – I found that, even though they are quite abstract, there are ghostly traces of shape and line that quietly announce themselves. It sort of whispers to you.

There is often a kind of ethereal beauty in network maps. They resemble something living, fibrous, arterial. Brevity’s program achieves something rather different. It takes pictures – fragments of experience – and mixes them like a painter mixes pigments. The resulting colors and textures are reminiscent of deep, subconscious urges, like the color field paintings of Rothko, or Ad Reinhardt (thanks Alex). It portrays a kind of experiential network.

This was posted yesterday on the Gates Memory Blog, the discussion forum for our project (in collaboration with Flickr), “The Gates: An Experiment in Collective Memory.”

chirac vs. google

![]() French President Jacques Chirac has instructed the Bibliothè que Nationale de France to “draw up a plan” for a comprehensive online library of European literature to counter what is seen as the inevitably Anglo-Saxon bias of Google Print (see “non, merci”).

French President Jacques Chirac has instructed the Bibliothè que Nationale de France to “draw up a plan” for a comprehensive online library of European literature to counter what is seen as the inevitably Anglo-Saxon bias of Google Print (see “non, merci”).

Reuters story: Chirac Rivals Google with French Online Book Plan

a book by Lawrence Lessig and you

Lawrence Lessig is inviting everyone to help revise and update his landmark 1999 book Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace on a public wiki, as a way of drawing “upon the creativity and knowledge of the community.” (story in Mercury News)

From the site: “This is an online, collaborative book update; a first of its kind. Once the the project nears completion, Professor Lessig will take the contents of this wiki and ready it for publication. The

resulting book, Code v.2, will be published in late 2005 by Basic Books. All royalties, including the book advance, will be donated to Creative Commons.”

As an experiment with networked books, this has a couple of big things going for it. For one, it is a pre-existent work with a large reader community. Like a stone tossed in the water, it creates ripples. Version 2 might benefit by incorporating these ripples. Secondly, Lessig will retain ultimate editorial authority, so we can be pretty sure that the final revision will be focused and well-shaped. And lastly, Lessig’s subject is so vast, so multi-dimensional, that the book will almost certainly benefit from broad reader/writer input. And for someone like Lessig, who is as much an activist as a scholar, constantly running around the world spreading his ideas, it is a nice way of asking for assistance in the time-consuming process of updating of a book that the world needs sooner rather than later.

Incidentally, Lessig will be appearing on April 7 at the New York Public Library with Wilco frontman Jeff Tweedy to discuss the question, “Who Owns Culture?” moderated by Steven Johnson. (thanks, NEWSgrist)

Tweedy says: “A piece of art is not a loaf of bread. When someone steals a loaf of bread from the store, that’s it. The loaf of bread is gone. When someone downloads a piece of music, it’s just data until the listener puts that music back together with their own ears, their mind, their subjective

experience.”