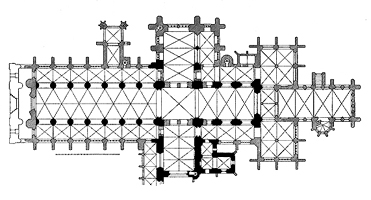

The World Wide Web is, quite possibly, the most collaborative multi-cultural project in the history of mankind. Millions of people have contributed personal homepages, blogs, and other sites to the growing body of human expression available online. It is, one could say, the secular equivalent of the medieval cathedral, designed by a professional, but constructed by non-professionals, regular folk who are eager to participate in the construction of a legacy. Such is the context for projects like Wikimedia and the Semantic Web, designed by elite programmers, built by the masses.

One of the most pressing questions with regard to collaborative authorship is, can the content be trusted? Does the anonymous group author have the same authority as the credentialed single author? Is our belief in the quality of information inextricably connected to our belief in the authority of the writer? Wikimedia (the non-profit organization that initiated Wikipedia, Wikibooks,, Wiktionary, Wikinews, Wikisource, and Wikiquote) addresses these concerns by offering a new model for collaborative authorship and peer review. Wikipedia’s anonymously published articles undergo peer review via direct peer revision. All revisions are saved and linked; user actions are logged and reversible. “This type of constant editing,” Wikimedia co-director Angela Beesley alleges, “allows you to trust the content over time.” The ambition of Wikimedia is to create a neutral territory where, through open debate, consensus can be reached on even the most contentious topics. The Wikimedia authoring system sets up a democratic forum where contributors construct their own rulespace and policies emerge from consensus-based, rather than top-down, processes. So the authority of the Wikimedia collaborative book depends, in part, on a collective self-discipline that is defined by and enforced by the group.

One of the most pressing questions with regard to collaborative authorship is, can the content be trusted? Does the anonymous group author have the same authority as the credentialed single author? Is our belief in the quality of information inextricably connected to our belief in the authority of the writer? Wikimedia (the non-profit organization that initiated Wikipedia, Wikibooks,, Wiktionary, Wikinews, Wikisource, and Wikiquote) addresses these concerns by offering a new model for collaborative authorship and peer review. Wikipedia’s anonymously published articles undergo peer review via direct peer revision. All revisions are saved and linked; user actions are logged and reversible. “This type of constant editing,” Wikimedia co-director Angela Beesley alleges, “allows you to trust the content over time.” The ambition of Wikimedia is to create a neutral territory where, through open debate, consensus can be reached on even the most contentious topics. The Wikimedia authoring system sets up a democratic forum where contributors construct their own rulespace and policies emerge from consensus-based, rather than top-down, processes. So the authority of the Wikimedia collaborative book depends, in part, on a collective self-discipline that is defined by and enforced by the group.

The collaborative authoring environment engendered by the web will make even more ambitious and far-reaching projects possible. Projects like the Semantic Web, which aims to make all content searchable by allowing users to assign semantic meaning to their work, will organize the prodigious output of collaborative networks, and could, potentially, cast the entire web as a collaboratively authored “book.”

if:book

A Project of the Institute for the Future of the Book

I was talking with a representative of our town administrative staff who pointed out that keeping up with the town’s municipal code is something like an interactive book. New resolutions are being passed all the time, and keeping track of it all can be a nightmare. Something like Wikipedia (but with updates restricted to relevant members of town staff) might be the ideal way to record the municipal code. The law books could be updated in real time, and town residents could even post comments or questions, right on the web page next to the relevant regulations.

Interesting. The networked book as a tool for enhancing the democratic process. Let’s dream big…what if the federal budget were accessible to taxpayers as an online interactive forum. Imagine Wikibudget!

Can (web) content be trusted? All content can be trusted. The blatant distortions, ineptitudes, corruptions and pure fantasies as well as authorized canon. In fact our documentary heritage is exactly such a composite.

The question is can content be trusted to persist. The agents of selection and review transpire across time and cultures, so we must trust in the persistence of conceptual works if knowledge is to be built.

And web caching is not the whole answer here. That archival path just leads to deeper arrays beyond bionic capacity for either veneration or deliberate neglect. The search result will be one star in a field not different from another star in the field. The star field is the metaphor for the pixel display…it isn’t even print.