Amazon’s search engine A9 has recently unveiled a new service: yellow pages “like you’ve never seen before.”

“Using trucks equipped with digital cameras, global positioning system (GPS) receivers, and proprietary software and hardware, A9.com drove tens of thousands of miles capturing images and matching them with businesses and the way they look from the street.”

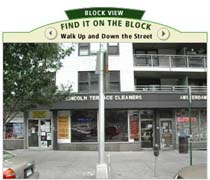

All in all, more than 20 million photos were captured in ten major cities across the US. Run a search in one of these zip codes and you’re likely to find a picture next to some of the results. Click on the item and you’re taken to a “block view” screen, allowing you to virtually stroll down the street in question (watch this video to see how it works). You’re also allowed, with an Amazon login, to upload your own photos of products available at listed stores. At the moment, however, it doesn’t appear that you can contribute your own streetscapes. But that may be the next step.

All in all, more than 20 million photos were captured in ten major cities across the US. Run a search in one of these zip codes and you’re likely to find a picture next to some of the results. Click on the item and you’re taken to a “block view” screen, allowing you to virtually stroll down the street in question (watch this video to see how it works). You’re also allowed, with an Amazon login, to upload your own photos of products available at listed stores. At the moment, however, it doesn’t appear that you can contribute your own streetscapes. But that may be the next step.

I can imagine online services like Mapquest getting into, or wanting to get into, this kind of image-banking. But I wouldn’t expect trucks with camera mounts to become a common sight on city streets. More likely, A9 is building up a first-run image bank to demonstrate what is possible. As people catch on, it would seem only natural that they would start accepting user contributions.  Cataloging every square foot of the biosphere is an impossible project, unless literally everyone plays a part (see Hyperlinking the Eye of the Beholder on this blog). They might even start paying – tiny cuts, proportional to the value of the contribution. Everyone’s a stringer for A9, or Mapquest, or for their own, idiosyncratic geo-caching service.

Cataloging every square foot of the biosphere is an impossible project, unless literally everyone plays a part (see Hyperlinking the Eye of the Beholder on this blog). They might even start paying – tiny cuts, proportional to the value of the contribution. Everyone’s a stringer for A9, or Mapquest, or for their own, idiosyncratic geo-caching service.

A9’s new service does have a predecessor though, and it’s nearly 30 years old. In the late 70s, the Architecture Machine Group, which later morphed into the MIT Media Lab, developed some of the first prototypes of “interactive media.” Among them was the Aspen Movie Map, developed in 1978-79 by Andrew Lippman – a program that allowed the user to navigate the entirety of this small Colorado city, in whatever order they chose, in winter, spring, summer or fall, and even permitting them to enter many of the buildings. The Movie Map is generally viewed as the first truly interactive computer program. Now, with the explosion of digital photography, wireless networked devices, and image-caching across social networks, we might at last be nearing its realization on a grand scale.

if:book

A Project of the Institute for the Future of the Book