The year is 2014, and “everyone contributes to the living, breathing mediascape” by way of EPIC, the Evolving Personalized Information Construct. EPIC results when the hegemony of Googlezon (a media giant formed by the merging of Amazon.com and Google) trumps the Microsoft-friendster-newsbotster alliance, having long since obsoleted conventional news agencies. The “news wars” of 2010 are forever settled when Googlezon begins employing “fact stripping” technologies that customize news, usually bastardizing the truth in the process.

EPIC 2014 by Robin Sloan and Matt Thompson is an eight minute Flash production that charts the evolution of capitalist concerns in the digital world via flickering, faux-historic-newsreel footage that is as riveting to watch as a twenty-car pile up on the freeway.

Not only do Googlezon subscribers gain unlimited space in which to post the minutiae of their lives via Google Grid, they also shape their very own worldview by using “editors” which will harvest and (re)combine news that’s been mined from the torrent of available articles. Though the potential for an in depth and complex view of the world is afforded, “for too many” EPIC consists of a “collection of trivia, much of it untrue, all of it narrow and sensational”; thus, in “feeble protest” the New York Times goes offline, the “slumbering fourth estate” having awoken far too late.

This piece is a very sobering one to view immediately before I embark upon the Media Literacy class I’ve been so pumped about teaching. Indeed EPIC 2014 is not the work of chicken-little extremists, but issues from savvy techno-cultural critics and their cautionary tale is one that should give pause to any of us concerned with the future of the book (or any other communicative vehicle for that matter) in a consumer-driven individualistic society.

I think I’ve found the perfect text for the fist day of class….

Monthly Archives: January 2005

the book is doomed

“The book is doomed.” That was Steven Pemberton‘s definitive answer to my musings about the future of the book in the digital age. It was the end of the first day of an international conference on web design, we were at the Friday night conference dinner, eating a crè me brulee that had been set ablaze just minutes before, and I don’t mean the little blue acetylene flame that puffs out after a few seconds. The chef blasted our crè me brulee for several minutes with a torch that looked like something a forest ranger would use to execute a controlled burn.

“The book is doomed.” That was Steven Pemberton‘s definitive answer to my musings about the future of the book in the digital age. It was the end of the first day of an international conference on web design, we were at the Friday night conference dinner, eating a crè me brulee that had been set ablaze just minutes before, and I don’t mean the little blue acetylene flame that puffs out after a few seconds. The chef blasted our crè me brulee for several minutes with a torch that looked like something a forest ranger would use to execute a controlled burn.

So, I’m eating my crè me brulee, trying to understand this pronouncement; when someone like Steven Pemberton says that the book, in the digital age, is doomed, you have to take it seriously. He cites The Innovator’s Dilemma, by Clayton M. Christensen. The thesis, Pemberton explains, has to do with the process of innovation and adoption. A new invention has to find a niche market that will allow it to improve and develop. Once the new invention advances enough to allow it to compete with the entrenched technology it is quickly adopted. This often radically changes an industry. Pemberton gives computer printers as an example. Anyone remember the old dot matrix printers? They had gears on the side that fit into corresponding holes in the paper. Remember how slow they were and how poor the quality was? The introduction of the laser printer made vast improvements in printer quality and as soon as printer technology improved, a revolution in desktop publishing was made possible.

The book, Pemberton contends, will experience a similar sea-change the moment screen technology improves enough to compete with the printed page.

writer invites remix of story

Sci fi writer Benjamin Rosenbaum announced today that he has placed his short story Start the Clock under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Sharealike license, inviting readers and writers not only to share and reproduce (non-commercially) his work, but also to alter, rewrite, or remix it as they like.

Sci fi writer Benjamin Rosenbaum announced today that he has placed his short story Start the Clock under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Sharealike license, inviting readers and writers not only to share and reproduce (non-commercially) his work, but also to alter, rewrite, or remix it as they like.

This is not the first story Rosenbaum has made available under a CC license, but it is the first time he has explicitly welcomed derivative works and alteration of his material. Start the Clock began as part of Frank Wu’s Exquisite Corpuscule project, a riff on the classic parlor game the Exquisite Corpse, in which phrases, even stories, are woven from the free associations of the players. Supposedly, the first phrase ever yielded by this method was “the exquisite corpse will drink the young wine,” hence the name. So “unfreezing” this story is, in a way, only the most recent step in an ongoing experiment.

It is also marks the latest stage of a writer’s hard but fruitful struggle with the notions of sharing, permission, and piracy in a digital world. Writing on his blog last July, he ruminated on the evolvution of his ideas vis a vis copyright:

“So I kept intending to write the piratical bloggers nice letters, full of appreciation, expressing how honored I was, while gently educating them on copyright law. And then magnanimously assigning them noncommercial reprint rights ex post facto, in return for a link to my site.

“It was never that inspiring a project though, and I never did it. Something felt weird about it. Like I was greeting a spontaneous expression of love with rules-lawyering. It would be a different matter if I firmly believed pirates were a scourge of artists, like Madonna and Harlan Ellison do. But I don’t. I think there will be some ugly growing pains as antiquated business and revenue models adjust to cheap pervasive networking power and digitalization, but that ultimately freeloaders are useful. So it was like I’d be sending these letters on some kind of pedantic principle.”

german library obtains “license to copy”

Germany’s national library, Deutsche Bibliothek, has been made exempt from key provisions of the European Union Copright Directive, giving it the exclusive right “to crack and duplicate DRM-protected e-books and other digital media such as CD-Audio and CD-Roms” (check out post on mobileread).

Germany’s national library, Deutsche Bibliothek, has been made exempt from key provisions of the European Union Copright Directive, giving it the exclusive right “to crack and duplicate DRM-protected e-books and other digital media such as CD-Audio and CD-Roms” (check out post on mobileread).

Further in mobileread: “The Deutsche Bibliothek achieved an agreement with the German Federation of the Phonographic Industry and the German Booksellers and Publishers Association after it became obvious that copy protections would not only annoy teenage school boys, but also prohibit the library from fulfilling its legal mandate to collect, process and bibliographic index important German and German-language based works.”

Heartening to see a top-down hack like this.

see also threads on BoingBoing (German libraries can circumvent DRM) and Slashdot

the chilling effect of copyright law

excellent article in the Toronto Globe and Mail today about the chilling effect of copyright law on documentary films. initial subject is Eyes on the Prize, the superb documentary of the civil war struggle in the U.S., which is no longer shown on TV or distributed because the rights to the historic footage have run out and the producer’s cannot afford to re-purchase them in today’s hyper-inflated rights market.

the present of print-on-demand

I went to Boston over the weekend and grabbed a book at random from my bookshelf for reading on the trip – an English translation of Gabriele D’Annunzio’s Il Piacere. D’Annunzio is probably best known to English-speaking audiences as being the novelist in residence for the Fascists – which he was – though he’s also the closest thing the Italians have to Proust. I’ve meant to read D’Annunzio for a while out of a vague sense of duty; however, you don’t often see him in English translations, and when I saw this copy for sale in a used book store a few months ago, I picked it up. Little did I suspect that it would provide fodder for rumination about the present and future of the book and publishing.

I went to Boston over the weekend and grabbed a book at random from my bookshelf for reading on the trip – an English translation of Gabriele D’Annunzio’s Il Piacere. D’Annunzio is probably best known to English-speaking audiences as being the novelist in residence for the Fascists – which he was – though he’s also the closest thing the Italians have to Proust. I’ve meant to read D’Annunzio for a while out of a vague sense of duty; however, you don’t often see him in English translations, and when I saw this copy for sale in a used book store a few months ago, I picked it up. Little did I suspect that it would provide fodder for rumination about the present and future of the book and publishing.

From the start, there seemed to be something a little bit off with this book. The punctuation of the title seems to be in a state of flux: “Il Piacere The Pleasure” says the front cover, “Il Piacere – The Pleasure” says the spine, and “Il Piacere (The Pleasure)” says the title page. The author’s name is spelled “D’annunzio” on the cover, “d’Annunzio” on the title page, and “D’Annunzio” on an about-the-author page after the title page. The back cover doesn’t say mention the title or the author, because it’s devoted to advertising for the publisher, 1stBooksLibrary.com. A visit to the company’s website made things much more clear: 1stBooksLibrary.com, now AuthorHouse.com, is essentially an online vanity press. For about $700 (as far as I can tell), they’ll publish your book for you – in paperback and even in ebook form if you’re willing to pay extra. Sadly, one can’t get “Il Piacere The Pleasure” as an ebook. What seems to have happened here is that the translator, who I won’t name, paid to have her translation of Il Piacere published. But more on the publisher later.

This book was clearly a labor of love. I won’t comment about the quality of the translation, save to say that D’Annunzio’s language is frilly in Italian, but reaches new levels of rococo here. I’m more interested in the book as an artifact. And an interesting artifact it is. The confusion of its cover (the background image which seems to be a family snapshot of the Spanish Steps from the 1950s) continues inside. The spelling isn’t perfect in English: I suspect the trouble of dealing with all the Italian words (large patches are left untranslated, one presumes for color) and proper names made it annoying to run a spellcheck on it. It’s even worse in Italian: on the first page, we find the church at the top of the Spanish Steps (Trinità dei Monti) referred to as both “Trinita de’ Monti” and “Trinita dei Monti”. And even a bilingual spell-checker wouldn’t prevent malapropisms like the one on p. 29, where we learn that a character is subject “to unseen tenderness, to quick melancholy, to raped anger” – which makes your eyes widen until you realize that word should be “rapid”.

Just as troublesome is the punctuation. Italian, like French, uses a long dash before direct discourse, called a lineetta. Although Joyce did his best tried to convert us to the French method, most English novels still use quotation marks. Here, both are used, kind of: there’s a hyphen and a space before every quotations, like this:

– “Come, come!”, Andrea said to Elena, taking her arm, after having left some money on the table.

Repeated over 281 pages, this soon ceases to be cute and becomes wearing. Dashes between phrases also become hyphens. There are two spaces after every period, a rule of thumb which should have disappeared with the typewriter. There’s no hyphenation at the end of lines, which leads to large gaps between words. And the superstructure of the book is a mess. The four sections of the book are headed “Book I”, “LIBRO SECONDO – SECOND BOOK”, “LIBRO TERZO – THIRD BOOK”, and finally, a terse “LIBRO”. I could go on.

It’s a laudable aim – I think it’s great that anyone can translate D’Annunzio on their own, and it’s fantastic to live in an age when anyone can publish such a thing, and I think the translator should be congratulated on her achievement. What this might point to, however, is a downside of a future without publishers. Nobody needs an editor to be published any more, or a book designer, or even a proofreader, which is a radical change in how books can be produced. But just because you can do it yourself doesn’t necessarily obviate the need for them. This book needed a copy editor badly. A designer and a regular editor to make helpful advice wouldn’t have hurt anything. Had I not taken such glee in marking up the textual infelicities, I almost certainly would not have persevered through the book.

Visiting AuthorHouse.com, I’m not sure what to think. (There, for what it’s worth, the title of the book I have is Il Piacere, The Pleasure.) They’ve published some reasonably reputable things – a book by Senator Dick Lugar, for example, is currently being promoted on the front page. Searching for them as a publishing house on Amazon.com reveals that people are reviewing, and presumably buying, some of their books. Although Authorhouse publishes a huge number of books (they claim two million books, and over twenty thousand authors as of 2004), one can’t help wondering if it’s a scam. Kooks of all varieties seem to be well represented: one can buy a copy of The Shakespeare Code, The Book of Theories: Evolution, Metaphysics and Politics, or What Really Happens at the Rapture:: Rapture or Rupture- Your Choice, as well as such works of fiction as Nolocaust. Some of the people publishing there defy description: try reading a synopsis of any of the 31 (!) novels that the prodigious Robert James Warner has published through them, with such titles as Willy the Wonder Fish, That God Damned Hill!, and Robodick. It’s pretty clear that it’s a new variation on the old vanity press.

A less than scrupulous boss once told me that any kid out of junior high could do what I was doing as a book designer. That’s partly true. This copy of D’Annunzio was almost certainly written in MS Word, dumped into a 5” by 8” template and printed to a PDF, which was sent to the printers. A junior high kid could, with a bootleg copy of Adobe Acrobat and fifteen minutes of training, put out a book that looks much like these print-on-demand titles. A little more work and you’ve got your very own ebook. But it takes more than software, and I think that in our rush for new technology, that’s sometime forgotten. It’s great to do away with the infrastructure of publishing: it’s rotten and should have been done away with a long time ago. But the infrastructure of publishing – editors, proofreaders, designers – did ensure that books were readable. It’s hard for readers to take your book seriously if it looks like an amateur job. If you’re going to make your own books, you should make them well. There’s human work to be done for print on demand before we can take it seriously as one of the futures of publishing.

moleskinerie – the steadfast fetish

Last month, I had the good fortune to speak briefly with Peter Lunenfeld at the Scholarship in the Digital Age conference at USC. I was surprised to learn that this famous digital media theorist is currently obsessed with a print-based initiative. His new Mediaworks Pamphlets are “theoretical fetish objects for the 21st century” – elegantly produced collaborations between designer and writer, intended to break serious media theory out of “the hermetically sealed spheres of academia and the techno-culture” and into the public discourse, much like the famous collaboration between Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore, “The Medium is the Massage.” By shifting reading, writing and design practices to the screen, Lunenfeld argues, digital media have effectively “taken the weight off” of the print codex, enabling its tactile qualities to flower anew.

Last month, I had the good fortune to speak briefly with Peter Lunenfeld at the Scholarship in the Digital Age conference at USC. I was surprised to learn that this famous digital media theorist is currently obsessed with a print-based initiative. His new Mediaworks Pamphlets are “theoretical fetish objects for the 21st century” – elegantly produced collaborations between designer and writer, intended to break serious media theory out of “the hermetically sealed spheres of academia and the techno-culture” and into the public discourse, much like the famous collaboration between Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore, “The Medium is the Massage.” By shifting reading, writing and design practices to the screen, Lunenfeld argues, digital media have effectively “taken the weight off” of the print codex, enabling its tactile qualities to flower anew.  There is room now to play and invent in the realm of paper, and a resulting emphasis on the pursuit of pleasure and grace in the experience of book objects. As evidence of the resurgent fetish book, Lunenfeld points to the immaculate productions of McSweeney’s, which has made its mark by coupling serious literary output with elegant design at relatively low cost to the reader.

There is room now to play and invent in the realm of paper, and a resulting emphasis on the pursuit of pleasure and grace in the experience of book objects. As evidence of the resurgent fetish book, Lunenfeld points to the immaculate productions of McSweeney’s, which has made its mark by coupling serious literary output with elegant design at relatively low cost to the reader.

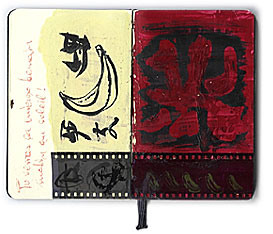

Another sign of this resurgence is the Moleskine phenomenon – those indelible oilskin-bound notebooks reissued in 1998 from the classic French design, famously employed by Chatwin in his travels, and, if the packaging is to be believed, by Hemingway, Van Gogh and Picasso as well.  Nowadays, Moleskines are favored by aesthetes and design sophisticates with a propensity for jotting things down, and is especially beloved by the blogging and techie communities, further evidence that this renewed fetish interest is intimately linked to the experience of networked, digital culture. In fact, Moleskine culture is a flourishing niche on the web, with blogs, art sites, and a full Wikipedia entry devoted solely to the flights of invention (Moleskine hacks etc.) and cult of personal record-keeping arising from this little black book.

Nowadays, Moleskines are favored by aesthetes and design sophisticates with a propensity for jotting things down, and is especially beloved by the blogging and techie communities, further evidence that this renewed fetish interest is intimately linked to the experience of networked, digital culture. In fact, Moleskine culture is a flourishing niche on the web, with blogs, art sites, and a full Wikipedia entry devoted solely to the flights of invention (Moleskine hacks etc.) and cult of personal record-keeping arising from this little black book.

Returning to Lunenfeld’s fetish theory with McSweeney’s as exemplar, it’s almost too perfect that McSweeney’s founder Dave Eggers’ new book of short stories, How We Are Hungry, should be bound exactly like a Moleskine, complete with elastic fastening band. But whereas my notebooks have held up admirably through miles of travel and years of abuse, the elastic strap of my copy of the Eggers book broke after a single day’s jostling in my bag. Take note, McSweeney’s…

networked book/book as network

Book as Network/Networked Book? That’s the koan I’ve been puzzling for the last few weeks. Can something made from, let’s say, hundreds of semi-anonymous contributors or commentors be considered a book? Is this what the texting generation is going to want–something a little less single-author, a little more…bloggy? The possibility makes me slightly sick and dizzy (I’m still paying student loans for a single-author oriented MFA in creative writing). At the same time it’s kind of exciting. Could, for example, my newest favorite blog Overheard in the Office a spin off of Overheard in New York be considered a dynamic anthology?

What about multi-player game-based narrative formats like Sims; are they the digital equivalent of networked novels? Bob recently sent me a link to an article entitled: Sims 2 hacks spread like viruses. Apparently, hackers have infected the Sims 2 universe, messing with individual games/narratives. About this Bob says: this seems so interesting to me if we consider it as one of the strands of future narrative where the author evolves into a god who creates a universe that people populate and mess with as people do; i.e. that the author creates a starting place for an unfolding story. Of course this has been a visible strand since the advent of computer games, especially the large multi-player ones — but for me the added bit here, that the mortals are messing with the game’s code and thus vastly increasing the scope of the game, brings the whole subject up with renewed interest.

The future book will be a networked book or a “processed book” as Joseph Esposito calls it. To process a book, he says, is more than simply building links to it; it also includes a modification of the act of creation, which tends to encourage the absorption of the book into a network of applications, including but not restricted to commentary.

A modification of the act of creation…what, exactly, does this mean for the craft of storytelling? Is it changing utterly? And is somebody going to tell the MFA programs?

btw. if you know any great examples of networked books let me know. I’m building a collection.

capturing the early history of interactive media

some of the most important early work in interactive media took place at the Architecture Machine Group Laboratory at MIT (now the Media Lab). twenty years ago the lab made a videodisc, Discursions, containing videos of several key experiments. this early work at MIT was crucial in terms of fueling and defining my ideas about interactive media (see books unbound article).

some of the most important early work in interactive media took place at the Architecture Machine Group Laboratory at MIT (now the Media Lab). twenty years ago the lab made a videodisc, Discursions, containing videos of several key experiments. this early work at MIT was crucial in terms of fueling and defining my ideas about interactive media (see books unbound article).

yesterday i met with a group of freshman in the interactive media honors program at the University of Southern California who signed up to work with the institute on presenting the Discursions material in some as-yet-to-be-decided form. the response was fantastic. (remember, these are young kids — none of whom were even born when Discursions was made). i know “awesome” is an overused word today, but that’s a good description of what the students thought of what they saw. many of the experiments seemed as if they could have been done yesterday and they grasped the importance of making the work available to young people working in the field now. any fears i had that my interest in the Discursions material was merely an oppty. to walk down memory lane disappeared immediately.

we’re planning to interview as many of the original researchers as possible, hoping that they can contextualize the work in terms of both its origin and its trajectory over the past twenty years.

powers of 10

The Pew Internet & American Life project’s recent report, The Future of the Internet, surveys the opinions of a broad assortment of scholars, web pioneers and technophiles on where they think the Internet is headed over the coming decade. Partnering with the Pew project, Elon University is running a related initiative, Imagining the Internet, which “examines the potential future of the Internet while simultaneously providing a peek back into its history.” The centerpiece of this project is a “Predictions Database,” pooling the prognostications of web luminaries and average joes alike. A great resource.

The Pew Internet & American Life project’s recent report, The Future of the Internet, surveys the opinions of a broad assortment of scholars, web pioneers and technophiles on where they think the Internet is headed over the coming decade. Partnering with the Pew project, Elon University is running a related initiative, Imagining the Internet, which “examines the potential future of the Internet while simultaneously providing a peek back into its history.” The centerpiece of this project is a “Predictions Database,” pooling the prognostications of web luminaries and average joes alike. A great resource.

Pew and Elon aren’t the only ones talking about that slender ten-year slice known as the history of the Internet. A conference next week in Amsterdam at The Institute of Network Cultures will be spending two days discussing “a decade of web design.” Future of the Book will be coming to you live from the conference.

Pew participants more or less agreed on a few broad projections: that publishing and the news will undergo further dramatic change as blogs and other web phenomena continue to break apart and redefine the mass media structures of the past century (see also the Pew report on blogging); that “the Internet will be more deeply integrated in our physical environments and high-speed connections will proliferate – with mixed results”; and that network infrastructure will likely suffer a major attack.

This last point is echoed in another recent speculative work, in this case, a work of fiction by former white house counter-terrorism chief Richard Clarke in the latest issue of The Atlantic Monthly (which annoyingly isn’t readable on the web without subscription). The story, titled Ten Years Later, is a concocted transcript of the Tenth Anniversary 9/11 Lecture given at the Kennedy School of Government in Cambridge. If you like having nightmares, go read this piece. At this imaginary lectern, Clarke delivers a hellish litany of terrorist attacks and domestic security crackdowns, painting an America even more paranoid and locked-down than the one we live in now. Among his grim predictions is “virtual war” in 2008 in the form of a “Zero Day worm” launched by Iran in cooperation with al-Qaeda which effectively shuts down the US economy.

This last point is echoed in another recent speculative work, in this case, a work of fiction by former white house counter-terrorism chief Richard Clarke in the latest issue of The Atlantic Monthly (which annoyingly isn’t readable on the web without subscription). The story, titled Ten Years Later, is a concocted transcript of the Tenth Anniversary 9/11 Lecture given at the Kennedy School of Government in Cambridge. If you like having nightmares, go read this piece. At this imaginary lectern, Clarke delivers a hellish litany of terrorist attacks and domestic security crackdowns, painting an America even more paranoid and locked-down than the one we live in now. Among his grim predictions is “virtual war” in 2008 in the form of a “Zero Day worm” launched by Iran in cooperation with al-Qaeda which effectively shuts down the US economy.

Scary stuff, but probably important to keep in the back of one’s mind as we try to imagine the future of books and communication in the digital era. Technology does not develop in a vacuum, nor does culture. Think of the massive creative response to the wars that ravaged the earth in the twentieth century. How will artists and culture as a whole respond to the ravaging of a virtual world that is increasingly as real as the material one?