Route 66: An American Bad Dream is an independent documentary film starring three Germans road tripping across the legendary US highway. What makes this film notable is that they released the film under the Creative commons license. Also, it had its premiere in the virtual world of Second Life on Aug 10th. The success of that showing prompted them to host an additional viewing this Thursday August 31 at 4PM SL in Kula 4, which will be presented by its creator Gonzo Oxberger. In the Open Source spirit of this project, they are making the video and audio project files available to anyone with a serious interest in remixing the film.

Category Archives: Remix

lulu.tv testing some boundaries of copyright

Lulu.tv made recent news with their new video sharing service which has a unique business model. Bob Young the head of Lulu.tv and founder of the self publishing service Lulu.com also founded Red Hat, which commercially sells open source software. He has been doing interesting experiments in creating business that harness the creative efforts of people.

Lulu.tv made recent news with their new video sharing service which has a unique business model. Bob Young the head of Lulu.tv and founder of the self publishing service Lulu.com also founded Red Hat, which commercially sells open source software. He has been doing interesting experiments in creating business that harness the creative efforts of people.

The new revenue sharing strategy behind Lulu.tv is fairly simple. Anyone can post or view content for free, as with Google Video or YouTube. However, it offers a “pro” version, which charges users to post video. 80% of the fees paid by goes to an account and the money is distributed each month based on the number of unique downloads to subscribing members.

This strategy has a similar tone to the ideas of Terry Fisher who has been promoting and the related idea of an alternative media cooperative model. In Fisher’s model, viewers (rather than the content creators) pay a media fee to view content and the collected revenues are redistributed to the creators in the cooperative. Lulu.tv makes logical adjustments to the Fisher model because other video sharing services are already offering their content for free. Because there are a lot more viewers of these sites than posters, the potential revenue has limited growth. However, I can imagine if the economic incentive becomes great enough, then the best content could gravitate to Lulu.tv and they could potentially charge viewers for that content. Alternatively, revenue from paid advertising could be added the pool of funds for “pro” users.

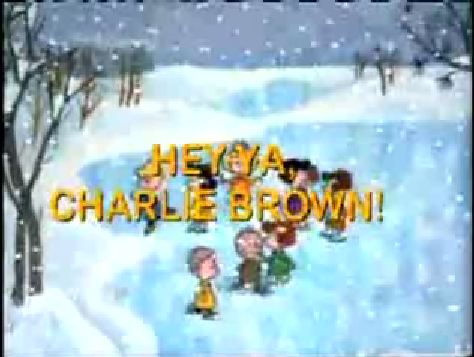

Introducing money into environments also produces friction and video sharing will be no different. Moving content from a free service to a pay service will increase copyright concerns, which have yet to be discussed. People tend to post “other people’s content” on YouTube and GoogleVideo, which often contains copyrighted material. For example, Hey Ya, Charlie Brown scores a Charlie Brown Christmas Special with Outkast’s hit single. It is not clear if this video was posted by a pro user, or who made the video and if any rights were cleared. Although, for instance, YouTube takes down content when asked to by copyright holders, many holders do not complain because that media (for instance 80s music videos) have limited or no replay value. With video remixes, creators have traditionally given away their work and allow it to be shared because there was no or little earning potential for the remixes. However with Lulu.tv’s model, this media is suddenly able to generate money. Remixers who have traditionally allows the viral distribution of their work, now they have an economic incentive to host their content in one specific location and hence control the distrbution of the work (sound familiar?)

Introducing money into environments also produces friction and video sharing will be no different. Moving content from a free service to a pay service will increase copyright concerns, which have yet to be discussed. People tend to post “other people’s content” on YouTube and GoogleVideo, which often contains copyrighted material. For example, Hey Ya, Charlie Brown scores a Charlie Brown Christmas Special with Outkast’s hit single. It is not clear if this video was posted by a pro user, or who made the video and if any rights were cleared. Although, for instance, YouTube takes down content when asked to by copyright holders, many holders do not complain because that media (for instance 80s music videos) have limited or no replay value. With video remixes, creators have traditionally given away their work and allow it to be shared because there was no or little earning potential for the remixes. However with Lulu.tv’s model, this media is suddenly able to generate money. Remixers who have traditionally allows the viral distribution of their work, now they have an economic incentive to host their content in one specific location and hence control the distrbution of the work (sound familiar?)

I’m quite glad that Lulu.tv is experimenting in this vein. If it succeeds, the end effect will push the once fringe media and distribution even deeper into the mainstream. For people concerned with overreaching copyright protection, this could be also be disastrous depending on how we as a culture decide to accept it. The copyright holders could use Lulu.tv has a further argument for yet stronger protections to intellectual property. On the other hand, it could mainstream the idea that remixing is a transformative use. The tensions between media producers, copyright holders, distributors and viewers continue to be evolve and are important to document and note as they move forward.

from the real to the virtual and back again

In 2004, as the Matrix Ping Pong video link bounced its way from inbox to inbox, people where amused by the re-creation of a ping pong match with Matrix style special effects, using people instead of computer technology. Viewers were amazed at the elaborate costumes, only to be topped by even more amazing choregraphy. Perspective changes and camera angles are reproduced. Influences of Matrix 360 camera spinning and earlier Cantonese martial arts films are pervasive. Part of its success was the evident work and planning that was required to design and execute the scene. The idea of simulating the simulated was both ingenious and topical. However media criticism aside, it’s just a pleasure to watch.

The clip comes from a popular Japanese television show Kasou Taishou, where contestants performs skits before a panel of judges. These skits often involve re-creating camera work and special effects of film. That same year, Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe of the UK pop band Pet Shop Boys release the video for the song “Flamboyant.” In the video, a (stereo)typical Japanese corporate employee is seen struggling to design a skit for the show. Interspersed in the video are mock Japanese ads starring Tennant and Lowe. Two years later, they take the idea one step further recently their their new video, for “I’m with Stupid.” In it, Matt Lucas and David Walliamsthe stars of the British comic skit series “Little Britian” to replicate PBS videos “Go West” and “Can You Forgive Her.” The result is a bizarre re-intereption of the CGI intensive PBS videos.

When I first started on this post, I was going to try to say that these examples are a “reaction” to the increasing virtual parts of lives. However, my thinking has shifted towards this reading this phenomenon as the process of “reflection” that has a long traditional in cultural production. As our lives are becoming increasingly virtual, synthetic, and digital, our analogue lives reflect back the new digital nature of what we experience. Like a house of mirrors, people are reflecting back what they see. These mirrors, as found in the amusement parks, distort the original image, bending and stretching people’s reflection, but not beyond recognition. The participants on Kasou Taishou started copying the images from the Matrix, which itself is a reflection or new interpretation of the fight choreography of Cantonese martial arts films. Pet Shop Boys first merely replay their reflection (with splices of fake Japanese commerical staring themselves.) Things get much more interesting when Tennant and Lowe realize that the truly interesting part of the Flamboyant video was re-creating the digital with the analogue, while adding their own personal distortion through a distinctly British comedic lens.

Advances in telecommunication and media production technology have blown open the opportunity to create and share these types of cultural call and response we are witnessing. The history of parody is a prime example of this, a traditional cultural dialogue through media artifacts. I’m not all surprised, in this case, that Japan is playing a role here. In that, I have always been both fascinated and amazed by the observed way that Japanese culture seems to balance the respect of tradition with the advancement of modernity, especially with technology. Although, I realize that distance and language barriers may mask the tensions between these cultural forces. Part of the balance is achieved by taking the old and infusing it into the new rather than completely reject the old. Further, in the case of the real simulating the virtual, the diversity of modes of creation and distribution is extremely telling. Traditional roles are blurred. The one-to-many versus many-to-many broadcast models, East v. West cultural dominance, corporate v. independent media and pro/am production distinctions are being rendered meaningless. The end result is a far richer landscape of cultural production.

on ebay: collaborative fiction, one page at a time

Phil McArthur is not a writer. But while recovering from a recent fight with cancer, he began to dream about producing a novel. Sci-fi or horror most likely — the kind of stuff he enjoys to read. But what if he could write it socially? That is, with other people? What if he could send the book spinning like a top and just watch it go?

Say he pens the first page of what will eventually become a 250-page thriller and then passes the baton to a stranger. That person goes on to write the second page, then passes it on again to a third author. And a fourth. A fifth. And so on. One page per day, all the way to 250. By that point it’s 2007 and they can publish the whole thing on Lulu.

The fruit of these musings is (or will be… or is steadily becoming) “Novel Twists”, a ongoing collaborative fiction experiment where you, I or anyone can contribute a page. The only stipulations are that entries are between 250 and 450 words, are kept reasonably clean, and that you refrain from killing the protagonist, Andy Amaratha — at least at this early stage, when only 17 pages have been completed. Writers also get a little 100-word notepad beneath their page to provide a biographical sketch and author’s notes. Once they’ve published their slice, the subsequent page is auctioned on Ebay. Before too long, a final bid is accepted and the next appointed author has 24 hours to complete his or her page.

Networked vanity publishing, you might say. And it is. But McArthur clearly isn’t in it for the money: bids are made by the penny, and all proceeds go to a cancer charity. The Ebay part is intended more to boost the project’s visibility (an article in yesterday’s Guardian also helps), and “to allow everyone a fair chance at the next page.” The main point is to have fun, and to test the hunch that relay-race writing might yield good fiction. In the end, McArthur seems not to care whether it does or not, he just wants to see if the thing actually can get written.

Surrealists explored this territory in the 1920s with the “exquisite corpse,” a game in which images and texts are assembled collaboratively, with knowledge of previous entries deliberately obscured. This made its way into all sorts of games we played when we were young and books that we read (I remember that book of three-panel figures where heads, midriffs and legs could be endlessly recombined to form hilarious, fantastical creatures). The internet lends itself particularly well to this kind of playful medley.

war machinima

Ray, Bob and I spent last week out in Los Angeles at our institutional digs (the Annenberg Center for Communication at USC), where we held a pair of meetings with professors from around the US and Canada to discuss various coups we are attempting to stage within the ossified realm of scholarly and textbook publishing. Following these, we were able to stick around for a fun conference/media festival organized by Annenberg’s Networked Publics project.

The conference was a mix of the usual academic panels and a series of curated mini-exhibits of “do-it-yourself” media, surveying new genres of digital folk art currently proliferating across the net such as political remix movies, anime music videos, “digital handmade” art projects (which featured the near and dear Alex Itin — happy birthday, Alex!), and of course, machinima: films made inside of video game engines.

As we enjoyed this little feast of new media, I was vaguely aware that the Tribeca film festival was going on back in New York. As I casually web-surfed through one of the panels — in the state of continuous partial attention that is now the standard state of being all these networky conferences — I came across an article about one of the more talked about films appearing there this year: “The War Tapes.” Like Gunner Palace and Occupation Dreamland, “The War Tapes” is a documentary about American soldiers in Iraq, but with one crucial difference: all the footage was shot by actual soldiers.

As we enjoyed this little feast of new media, I was vaguely aware that the Tribeca film festival was going on back in New York. As I casually web-surfed through one of the panels — in the state of continuous partial attention that is now the standard state of being all these networky conferences — I came across an article about one of the more talked about films appearing there this year: “The War Tapes.” Like Gunner Palace and Occupation Dreamland, “The War Tapes” is a documentary about American soldiers in Iraq, but with one crucial difference: all the footage was shot by actual soldiers.

Back in 2004, director Deborah Scranton gave video cameras to ten members of the New Hampshire National Guard who were about to depart for a yearlong tour in Iraq. They went on to shoot a combined 800 hours of film, the pared-down result of which is “The War Tapes.” Reading about it, I couldn’t help but think that here was a case of real-life machinima. Give the warriors cameras and glimpse the war machine from the inside — carve out a new game within the game.

Granted, it’s a far from perfect analogy. Machinima involves a total repurposing of the characters and environment, foregoing the intended objectives of the game. In “The War Tapes,” the soldiers are still on their mission, still within the chain of command. And of course, war isn’t a video game. But isn’t it advertised as one?

Time Square, New York City (the military-entertainment complex)

There’s something undeniably subversive about giving cameras to GIs in what is such a thoroughly mediated war, a sort of playing against the game — if not of the game of occupation as a whole, then at least the game of spin. “I’m not supposed to talk to the media,” says one soldier to Steve Pink, one of the film’s main subjects, as he attempts to conduct an interview. To which Pink replies: “I’m not the media, dammit!”

In the clips I found on the film’s promotional site (the general release is later this summer), the overriding impression is of the soldiers’ isolation and fear: the constant terror of roadside bombs, frantic rounds fired into the green night-vision darkness, swaddled in helmets and humvees and hi-tech weaponry. It’s a frightening game they play. Deeply impersonal and anonymous, and in no way resembling the pumped-up, guitar-screeching game that the military portrays as war in its recruiting ads. This is the horrible truth at the bottom of the “Army of One” slogan: you are a lone digit in a massive calculation. Just pray you don’t become a zero.

Yet naturally, they find their own games to play within the game. One clip shows the tiny, gruesome spectacle of two soldiers, in a moment of leisure, pitting a scorpion against a spider inside a plastic tub, reenacting their own plight in the language of the desert.

At the Net Publics conference, we did see see one example of genuine machinima that made its own spooky commentary on the war: a hack of Battlefield 2 by Swedish game forum Snoken that brilliantly apes the now-famous Sony Bravia commercial, in which 250,000 colored plastic balls were filmed cascading through the streets of a San Francisco.

Here’s Battlefield:

And here’s the original Sony ad:

McKenzie Wark doesn’t address machinima in GAM3R 7H30RY (which launches in about a week), but he does discuss video games in the context of the “military entertainment complex”: the remaking of postmodern capitalist society in the image of the digital game, in which every individual is a 1 or a 0 locked in senseless competition for advancement through the levels, each vying to “win” the game:

The old class antagonisms have not gone away, but are hidden beneath levels of rank, where each agonizes over their worth against others in the price of their house, the size of their vehicle and where, perversely, working longer and longer hours is a sign of winning the game. Work becomes play. Work demands not just one’s mind and body but also one’s soul. You have to be a team player. Your work has to be creative, inventive, playful – ludic, but not ludicrous.

Video games (which can actually be won) are allegories of this imperfect world that we are taught to play like a game, as though it really were governed by a perfect (and perfectly fair) algorithm — even the wars that rage across its hemispheres:

Once games required an actual place to play them, whether on the chess board or the tennis court. Even wars had battle fields. Now global positioning satellites grid the whole earth and put all of space and time in play. Warfare, they say, now looks like video games. Well don’t kid yourself. War is a video game – for the military entertainment complex. To them it doesn’t matter what happens ‘on the ground’. The ground – the old-fashioned battlefield itself – is just a necessary externality to the game. Slavoj Zizek: “It is thus not the fantasy of a purely aseptic war run as a video game behind computer screens that protects us from the reality of the face to face killing of another person; on the contrary it is this fantasy of face to face encounter with an enemy killed bloodily that we construct in order to escape the Real of the depersonalized war turned into an anonymous technological operation.” The soldier whose inadequate armor failed him, shot dead in an alley by a sniper, has his death, like his life, managed by a computer in a blip of logistics.

How does one truly escape? Ultimately, Wark’s gamer theory is posed in the spirit that animates the best machinima:

The gamer as theorist has to choose between two strategies for playing against gamespace. One is to play for the real. (Take the red pill). But the real is nothing but a heap of broken images. The other is to play for the game (Take the blue pill). Play within the game, but against gamespace. Be ludic, but also lucid.

on appropriation

The Tate Triennial 2006, showcasing new British Art, brings together thirty-six artists who explore the reuse and reshaping of cultural material. Curated by Beatrix Ruf, director of the Kunsthalle in Zurich, the exhibition includes artists from different generations who explore reprocessing and repetition through painting, drawing, sculpture, photography, film, installations and live work.

Historically, the appropriation of images and other cultural matter has been practiced by societies as the reiteration, reshuffling, and eventual transformation of artistic and intellectual human manifestations. It covers a vast range from tribute to pastiche. When visual codes are combined, the end product is either a cohesive whole where influences connect into new and very personal languages, or disparate combinations where influences compete and clash. In today’s art, the different guises of repetition, from collage and montage to file sharing and digital reproduction highlight the existing codes or reveal the artificiality of the object. Today’s combination of codes alludes to a collective sense of memory in a moment when memories have become literally photographic.

One comes out of this exhibition thinking about Duchamp‘s “readymades,” Rauschenberg’s “combines,” and other forms of conceptual “gluing,” (the literal meaning of the word “collage,”) as precursors and/or manifestations of the postmodern condition. This show is a perfect representation of our moment. As Beatrix Ruf says in the catalogue: “Artists today are forging new ways of making sense of reality, reworking ideas of authenticity, directness and social relevance, looking again into art practices that emerged in the previous century.”

We have artists like Michael Fullerton, who paints contemporary figures in the style of Gainsborough, or Luke Fowler‘s use of archive material to explore the history of Cornelius Cardew’s Scratch Orchestra. Repetition goes beyond inter-referentiality in the work of Marc Camille Chaimowicz, who combines works he made in the 70s with projected images of himself as a young man and as an adult, within a space where a vase of flowers set on a Marcel Breuer’ table and a pendulum swinging back and forth position the images of the past solidly in the present. In “Twelve Angry Women,” Jonathan Monk affixes to the wall twelve found drawings by an unknown artist from the 20s, using different colored pins that work as earrings. Mark Leckey uses Jeff Koons’ silver bunny as a mirror into his studio in the way 17th century masters painted theirs. Liam Gillick creates sculptures of hanging texts made out of factory signage.

Art itself is cumulative. Different generations build upon previous ones in a game of action and reaction. One interesting development in art today is the collective. Groups of artists coming together in couples, teams, or cyberspace communities, sometimes under the identity of a single person, sometimes a single person assuming a multiple identity. Collectives seem to be a new phenomenon, but their roots go back to the concept of workshops in antiquity where artistic collaboration and copying from casts of sculptural masterpieces was the norm. The notion of the individual artist producing radically new and original art belongs to modernity. The return to collectives in the second part of the 20th century, and again now, has a lot to do with the nature of representation, with the desire to go beyond the limits of artistic mimesis or individual interpretation.

On the other hand, appropriation as a form of artistic expression is a postmodern phenomenon. Appropriation is the language of today. Never before the advent of the Internet had people appropriated knowledge, spaces, concepts, and images as we do today. To cite, to copy, to remix, to modify are part of our everyday communication. The difference between appropriation in the 70s and 80s and today resides in the historical moment. As Jean Verwoert says in the Triennial 2006 catalogue:

The standstill of history at the height of the Cold War had, in a sense, collapsed the temporal axis and narrowed the historical horizon to the timeless presence of material culture, a presence that was exacerbated by the imminent prospect that the bomb could wipe everything out at any time. To appropriate the fetishes of material culture, then, is like looting empty shops at the eve of destruction. It is the final party before doomsday. Today, on the contrary, the temporal axis has sprung up again, but this time a whole series of temporal axes cross global space at irregular intervals. Historical time is again of the essence, but this historical time is not the linear or unified timeline of steady progress imagined by modernity: it is a multitude of competing and overlapping temporalities born from the local conflicts that the unresolved predicaments of the modern regimes still produce.

Today, the challenge is to rethink the meaning of appropriation in a moment when capitalist commodity culture has become the determinant of our daily lives. The Internet is perhaps our potential Utopia (though “dystopian” seems to be the adjective of choice now.) But, can it be called upon to fulfill the unfulfilled promises of 20th century’s utopias? To appropriate is to resist the notion of ownership, to appropriate the products of today’s culture is to expose the unresolved questions of a world shaped by the information era. The disparities between those who are entering the technology era and those forced to stay in the times of early industrialization are more pronounced than ever. As opposed to the Cold War, where history was at a standstill, we live in a time of extreme historicity. Permanence is constantly challenged, how to grasp it all continues to be the elusive task.

truth through the layers

Pedro Meyer’s I Photograph to Remember is a work originally designed for CD ROM, that became available on the Internet 10 years later. I find it not only beautiful within the medium limitations, as Pedro says on his 2001 comment, but actually perfectly suited for both, the original CD ROM, and its current home on the internet . It is a work of love, and as such it has a purity that transcends all media.

Pedro Meyer’s I Photograph to Remember is a work originally designed for CD ROM, that became available on the Internet 10 years later. I find it not only beautiful within the medium limitations, as Pedro says on his 2001 comment, but actually perfectly suited for both, the original CD ROM, and its current home on the internet . It is a work of love, and as such it has a purity that transcends all media.

The photographs and their subject(s) have such degree of intimacy that forces the viewer to look inside and avoid all morbidity or voyeurism. The images are accompanied by Pedro Meyer’s voice. His narration, plain and to the point, is as photographic as the pictures are eloquent. The line between text and image is blurred in the most perfect b&w sense. The work evokes feelings of unconditional love, of hands held at moments of both weakness and strength, of happiness and sadness, of true friendship, which is the basis of true love. The whole experience becomes introspection, on the screen and in the mind of the viewer.

IPTR was originally a Voyager CD ROM, and it was the first ever produced with continuous sound and images, a possibility that completes, and complements, image as narration and vice-versa. The other day Bob Stein showed me IPTR on his iPod and expressed how perfectly it works on this handheld device. And, it does. IPTR is still a perfect object, and as those old photographs exist thanks to the magic of chemicals and light, this exists thanks to that “old” CD ROM technology, and will continue to exist inhabiting whatever medium necessary to preserve it.

I’ve recently viewed Joan de Fontcuberta’s shows in two galleries in Manhattan; Zabriskie and Aperture,) and the connections between IPTR and these works became obsessive to me. Fontcuberta, also a photographer, has chosen the Internet, and computer technology, as the media for both projects. In “Googlegrams,” he uses the Google image search engine to randomly select images from the Internet by controlling the search engine criteria with only the input of specific key words.

I’ve recently viewed Joan de Fontcuberta’s shows in two galleries in Manhattan; Zabriskie and Aperture,) and the connections between IPTR and these works became obsessive to me. Fontcuberta, also a photographer, has chosen the Internet, and computer technology, as the media for both projects. In “Googlegrams,” he uses the Google image search engine to randomly select images from the Internet by controlling the search engine criteria with only the input of specific key words.

These Google-selected images are then electronically assembled into a larger image, usually a photo, of Fontcuberta’s choosing (for example, the image of a homeless man sleeping on the sidewalk reassembled from images of the 24 richest people in the world, Lynddie England reassembled from images of the Abu Ghraib’s abuse, or a porno picture reassembled from porno sites.). The end result is an interesting metaphor for the Internet and the relationship between electronic mass media and the creation of our collective consciousness.

For Fontcuberta, the Internet is “the supreme expression of a culture which takes it for granted that recording, classifying, interpreting, archiving and narrating in images is something inherent in a whole range of human actions, from the most private and personal to the most overt and public.” All is mediated by the myriad representations on the global information space. As Zabriskie’s Press Release says, “the thousands of images that comprise the Googlegrams, in their diminutive role as tiles in a mosaic, become a visual representation of the anonymous discourse of the internet.”

Aperture is showing Fontcuberta’s “Landscapes Without Memory” where the artist uses computer software that renders three-dimensional images of landscapes based on information scanned from two-dimensional sources (usually satellite surveys or cartographic data.) In “Landscapes of Landscapes” Fontcuberta feeds the software fragments of pictures by Turner, Cézanne, Dalí, Stieglitz, and others, forcing the program to interpret this landscapes as “real.”

Aperture is showing Fontcuberta’s “Landscapes Without Memory” where the artist uses computer software that renders three-dimensional images of landscapes based on information scanned from two-dimensional sources (usually satellite surveys or cartographic data.) In “Landscapes of Landscapes” Fontcuberta feeds the software fragments of pictures by Turner, Cézanne, Dalí, Stieglitz, and others, forcing the program to interpret this landscapes as “real.”

These painted and photographic landscapes are transformed into three-dimensional mountains, rivers, valleys, and clouds. The result is new, completely artificial realities produced by the software’s interpretation of realities that have been already interpreted by the painters. In the “Bodyscapes” series, Fontcuberta uses the same software to reinterpret photographs of fragments of his own body, resulting in virtual landscapes of a new world. By fooling the computer Fontcuberta challenges the limits between art, science and illusion.

Both Pedro Meyer and Joan de Fontcuberta’s use of photography, technology and the Internet, present us with mediated worlds that move us to rethink the vocabulary of art and representation which are constantly enriched by the means by which they are delivered.

if:book-back mountain: emergent deconstruction

It’s Oscar weekend, and everyone seems to be thinking and talking about movies, including myself. At the institute we often talk about the discourse afforded by changes in technology, and it seems to be apropos to take a look at new forms of discourse in area of movies. A month or so ago, I was sent the viral Internet link of the week. Someone made a parody of the Brokeback Mountain trailer by taking its soundtrack and tag lines and remixng them with scenes from the flight school action movie, Top Gun. Tom Cruise and Val Kilmer are recast as gay lovers, misunderstood in the world of air to air combat. The technique of remixing a new trailer first appeared in 2005, with clips from the Shining recut as a romantic comedy to hilarious effect. With spot-on voiceover and Peter Gabriel’s “Solsbury Hill” as music, it similarly circulated the Internet, while consuming office bandwidth. The first Brokeback parody is uncertain, however, it inspired the p2p/ mashup (although some purists question whether these trailers are true mashup) community to create dozens of trailers. Virginia Heffernan in the New York Times gives a very good overview of the phenomenon, including the depictions of Fight Club, Heat, Lord of the Rings, and Stars War as a gay love story.

Some spoofs work better than others. The more successful trailers establish the parallels between the loner hero archetype of film and the outsider qualities of gay life. For example, as noted by Heffernana, Brokeback Heat, with limited extra editing, transforms Al Pacino and Robert DeNiro from a detective and criminal into lovers, who wax philosophically on the intrinsic nature of their lives and their lack of desire to live another way. Or in Top Gun 2: Brokeback Squadron, Tom Cruise and Val Kilmer exist in their own hyper-masculine reality outside of the understanding of others, in particular their female romantic counterparts. In Back to the Future, the relationship of mentor and hero is reinterpreted as a cross generational romance. Lord of the Rings: Brokeback Mount Doom successfully captures the analogy between the perilous journey of the hero and the experience of the disenfranchised. Here, the quest of Sam and Frodo is inverted into the quest to find the love that dares not speak its name. The p2p/ mashup community had come to the same conclusion (to, at times, great comic effect) that the gay community arrived at long ago, that male bonding (and its Hollywood representation) has a homoerotic subtext.

The loner heros found in the the Brokeback Mountain remixes are of particular interest. Over time, the successful parodies deconstruct the Hollywood imagery of the hero, and subsequently distill the archetypes of cinema. This process of distillation identifies key elements of the male hero. The common traits of the hero being that he lies outside the mainstream, cannot fight his rebel “nature”, often uses the guidance of a mentor and must travel a perilous journey of self discovery all rise to the surface of these new media texts. The irony plays out, when their hyper-masculinity are juxtaposed next to identical references of the supposed taboo gay experience.

On the other hand, the Arrested Development version contains titles thanking the cast and producers of the cancelled series, clips of Jason Bateman’s television family suggesting his latent homosexuality, and the Brokeback Mountain theme music. The disparate pieces make less sense, rendering it ultimately less interesting as a whole. Likewise, Brokeback Ranger, a riff on Chuck Norris in the Walker, Texas Ranger television series, is a collection of clips of the Norris fighting and solving crimes, with the prerequisite music, and titles that describe Norris ironic superhuman abilities including dividing by zero. Again, the references are not of the hero archetype and the piece, although mildly humorous, has limited depth.

A potentially new form of discourse is being created, in which the archetypes of media text emerge from their repeated deconstruction and subsequent reconstruction. From these works, an understanding of the media text appears through an emergent deconstruction. In that, the individual efforts need not be conscious or even intended. Rather, the funniest and most compelling examples are the remixes which correctly identify and utilize the traditional conventions in the media text. Therefore, their success is directly correlated to their ability to correctly identify the archetype.

The users may not have prior knowledge of the ideas of the hero described by Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Nor are they required to have read Umberto Eco’s deconstruction of James Bond, or Leslie Fiedler’s work on the homosexual subtext found in the novel. Further, each individual remix author does not need to set out to define the specific archetypes. What is most extraordinary is that their aggregate efforts gravitate towards the distilled archetype, in this case, the male bonding rituals of the hero in cinema. Some examples will miss the themes, which is inherent in all emergent systems. By the definition and nature of archetypes, the work that most resonate are the ones which most convincingly identify, reference, (and in this case, parody) the archetype. These analyses can be discovered by an individual, as Campbell, Eco, Jung and Fiedler did. Since their groundbreaking works, there is an abundance of deconstructing media text from the last fifty years. Here, the lack of intention, and the emergence of the archetypes through the aggregate is new. An important aspect of these aggregate analyses is that they could only come about through the wide availability of both access to the network and to digital video editing software.

At the institute, we expect that the dissemination of authoring tools and access to the network will lead to new forms of discourse and we look for occurrences of them. Emergent deconstruction is still in its early stages. I am excited by its prospects, but how far it can meaningfully grow is unclear. However, I do know that after watching thirty some versions of the Brokeback Mountain remixed trailers, I do not need to hear its moody theme music any more, but I suppose that is part of the process of emergent forms.

yahoo! ui design library

There are several reasons that Yahoo! released some of their core UI code for free. A callous read of this would suggest that they did it to steal back some goodwill from Google (still riding the successful Goolge API release from 2002). A more charitable soul could suggest that Yahoo! is interested in making the web a better place, not just in their market-share. Two things suggest this—the code is available under an open BSD license, and their release of design patterns. The code is for playing with; the design patterns for learning from.

There are several reasons that Yahoo! released some of their core UI code for free. A callous read of this would suggest that they did it to steal back some goodwill from Google (still riding the successful Goolge API release from 2002). A more charitable soul could suggest that Yahoo! is interested in making the web a better place, not just in their market-share. Two things suggest this—the code is available under an open BSD license, and their release of design patterns. The code is for playing with; the design patterns for learning from.

The code is squarely aimed at folks like me who would struggle mightily to put together a default library to handle complex interactions in Javascript using AJAX (all the rage now) while dealing with the intricacies of modern and legacy browsers. Sure, I could pull together the code from different sources, test it, tweak it, break it, tweak it some more, etc. Unsurprisingly, I’ve never gotten around to it. The Yahoo! code release will literally save me at least a hundred hours. Now I can get right down to designing the interaction, rather than dealing with technology.

The design patterns library is a collection of best practice instructions for dealing with common web UI problems, providing both a solution and a rationale, with a detailed explanation of the interaction/interface feedback. This is something that is more familiar to me, but still stands as a valuable resource. It is a well-documented alternate viewpoint and reminder from a site that serves more users in one day than I’m likely to serve in a year.

Of course Yahoo! is hoping to reclaim some mind-space from Google with developer community goodwill. But since the code is general release, and not brandable in any particular way (it’s all under-the-hood kind of stuff), it’s a little difficult to see the release as a directly marketable item. It really just seems like a gift to the network, and hopefully one that will bear lovely fruit. It’s always heartening to see large corporations opening their products to the public as a way to grease the wheels of innovation.

what I heard at MIT

Over the next few days I’ll be sifting through notes, links, and assorted epiphanies crumpled up in my pocket from two packed, and at times profound, days at the Economics of Open Content symposium, hosted in Cambridge, MA by Intelligent Television and MIT Open CourseWare. For now, here are some initial impressions — things I heard, both spoken in the room and ricocheting inside my head during and since. An oral history of the conference? Not exactly. More an attempt to jog the memory. Hopefully, though, something coherent will come across. I’ll pick up some of these threads in greater detail over the next few days. I should add that this post owes a substantial debt in form to Eliot Weinberger’s “What I Heard in Iraq” series (here and here).

![]()

Naturally, I heard a lot about “open content.”

I heard that there are two kinds of “open.” Open as in open access — to knowledge, archives, medical information etc. (like Public Library of Science or Project Gutenberg). And open as in open process — work that is out in the open, open to input, even open-ended (like Linux, Wikipedia or our experiment with MItch Stephens, Without Gods).

I heard that “content” is actually a demeaning term, treating works of authorship as filler for slots — a commodity as opposed to a public good.

I heard that open content is not necessarily the same as free content. Both can be part of a business model, but the defining difference is control — open content is often still controlled content.

I heard that for “open” to win real user investment that will feedback innovation and even result in profit, it has to be really open, not sort of open. Otherwise “open” will always be a burden.

I heard that if you build the open-access resources and demonstrate their value, the money will come later.

I heard that content should be given away for free and that the money is to be made talking about the content.

I heard that reputation and an audience are the most valuable currency anyway.

I heard that the academy’s core mission — education, research and public service — makes it a moral imperative to have all scholarly knowledge fully accessible to the public.

I heard that if knowledge is not made widely available and usable then its status as knowledge is in question.

I heard that libraries may become the digital publishing centers of tomorrow through simple, open-access platforms, overhauling the print journal system and redefining how scholarship is disseminated throughout the world.

![]()

And I heard a lot about copyright…

I heard that probably about 50% of the production budget of an average documentary film goes toward rights clearances.

I heard that many of those clearances are for “underlying” rights to third-party materials appearing in the background or reproduced within reproduced footage. I heard that these are often things like incidental images, video or sound; or corporate logos or facades of buildings that happen to be caught on film.

I heard that there is basically no “fair use” space carved out for visual and aural media.

I heard that this all but paralyzes our ability as a culture to fully examine ourselves in terms of the media that surround us.

I heard that the various alternative copyright movements are not necessarily all pulling in the same direction.

I heard that there is an “inter-operability” problem between alternative licensing schemes — that, for instance, Wikipedia’s GNU Free Documentation License is not inter-operable with any Creative Commons licenses.

I heard that since the mass market content industries have such tremendous influence on policy, that a significant extension of existing copyright laws (in the United States, at least) is likely in the near future.

I heard one person go so far as to call this a “totalitarian” intellectual property regime — a police state for content.

I heard that one possible benefit of this extension would be a general improvement of internet content distribution, and possibly greater freedom for creators to independently sell their work since they would have greater control over the flow of digital copies and be less reliant on infrastructure that today only big companies can provide.

I heard that another possible benefit of such control would be price discrimination — i.e. a graduated pricing scale for content varying according to the means of individual consumers, which could result in fairer prices. Basically, a graduated cultural consumption tax imposed by media conglomerates

I heard, however, that such a system would be possible only through a substantial invasion of users’ privacy: tracking users’ consumption patterns in other markets (right down to their local grocery store), pinpointing of users’ geographical location and analysis of their socioeconomic status.

I heard that this degree of control could be achieved only through persistent surveillance of the flow of content through codes and controls embedded in files, software and hardware.

I heard that such a wholesale compromise on privacy is all but inevitable — is in fact already happening.

I heard that in an “information economy,” user data is a major asset of companies — an asset that, like financial or physical property assets, can be liquidated, traded or sold to other companies in the event of bankruptcy, merger or acquisition.

I heard that within such an over-extended (and personally intrusive) copyright system, there would still exist the possibility of less restrictive alternatives — e.g. a peer-to-peer content cooperative where, for a single low fee, one can exchange and consume content without restriction; money is then distributed to content creators in proportion to the demand for and use of their content.

I heard that such an alternative could theoretically be implemented on the state level, with every citizen paying a single low tax (less than $10 per year) giving them unfettered access to all published media, and easily maintaining the profit margins of media industries.

I heard that, while such a scheme is highly unlikely to be implemented in the United States, a similar proposal is in early stages of debate in the French parliament.

![]()

And I heard a lot about peer-to-peer…

I heard that p2p is not just a way to exchange files or information, it is a paradigm shift that is totally changing the way societies communicate, trade, and build.

I heard that between 1840 and 1850 the first newspapers appeared in America that could be said to have mass circulation. I heard that as a result — in the space of that single decade — the cost of starting a print daily rose approximately %250.

I heard that modern democracies have basically always existed within a mass media system, a system that goes hand in hand with a centralized, mass-market capital structure.

I heard that we are now moving into a radically decentralized capital structure based on social modes of production in a peer-to-peer information commons, in what is essentially a new chapter for democratic societies.

I heard that the public sphere will never be the same again.

I heard that emerging practices of “remix culture” are in an apprentice stage focused on popular entertainment, but will soon begin manifesting in higher stakes arenas (as suggested by politically charged works like “The French Democracy” or this latest Black Lantern video about the Stanley Williams execution in California).

I heard that in a networked information commons the potential for political critique, free inquiry, and citizen action will be greatly increased.

I heard that whether we will live up to our potential is far from clear.

I heard that there is a battle over pipes, the outcome of which could have huge consequences for the health and wealth of p2p.

I heard that since the telecomm monopolies have such tremendous influence on policy, a radical deregulation of physical network infrastructure is likely in the near future.

I heard that this will entrench those monopolies, shifting the balance of the internet to consumption rather than production.

I heard this is because pre-p2p business models see one-way distribution with maximum control over individual copies, downloads and streams as the most profitable way to move content.

I heard also that policing works most effectively through top-down control over broadband.

I heard that the Chinese can attest to this.

I heard that what we need is an open spectrum commons, where connections to the network are as distributed, decentralized, and collaboratively load-sharing as the network itself.

I heard that there is nothing sacred about a business model — that it is totally dependent on capital structures, which are constantly changing throughout history.

I heard that history is shifting in a big way.

I heard it is shifting to p2p.

I heard this is the most powerful mechanism for distributing material and intellectual wealth the world has ever seen.

I heard, however, that old business models will be radically clung to, as though they are sacred.

I heard that this will be painful.