Jorge Luis Borges tells the story of “Funes, the Memorious,” a man from Uruguay who, after an accident, finds himself blessed with perfect memory. Ireneo Funes remembers everything that he encounters; he can forget nothing that he’s seen or heard, no matter how minor. As one might expect, this blessing turns out to be a curse: overwhelmed by his impressions of the world, Funes can’t leave his darkened room. Worse, he can’t make sense of the vast volume of his impressions by classifying them. Funes’s world is made up entirely of hapax legomena. He has no general concepts:

Jorge Luis Borges tells the story of “Funes, the Memorious,” a man from Uruguay who, after an accident, finds himself blessed with perfect memory. Ireneo Funes remembers everything that he encounters; he can forget nothing that he’s seen or heard, no matter how minor. As one might expect, this blessing turns out to be a curse: overwhelmed by his impressions of the world, Funes can’t leave his darkened room. Worse, he can’t make sense of the vast volume of his impressions by classifying them. Funes’s world is made up entirely of hapax legomena. He has no general concepts:

“Not only was it difficult for him to see that the generic symbol ‘dog’ took in all the dissimilar individuals of all shapes and sizes, it irritated him that the ‘dog’ of three-fourteen in the afternoon, seen in profile, should be indicated by the same noun as the dog of three-fifteen, seen frontally. His own face in the mirror, his own hands, surprised him every time he saw them.”

(p. 136 in Andrew Hurley’s translation of Collected Fictions.) Funes dies prematurely, alone and unrecognized by the world; while we are told that he died of “pulmonary congestion,” it’s clear that Funes has drowned in his memories. While there are advantages to remembering everything, Borges’s narrator realizes his superiority to Funes:

(p. 136 in Andrew Hurley’s translation of Collected Fictions.) Funes dies prematurely, alone and unrecognized by the world; while we are told that he died of “pulmonary congestion,” it’s clear that Funes has drowned in his memories. While there are advantages to remembering everything, Borges’s narrator realizes his superiority to Funes:

“He had effortlessly learned English, French, Portuguese, Latin. I suspect, nevertheless, that he was not very good at thinking. To think is to ignore (or forget) differences, to generalize, to abstract. In the teeming world of Ireneo Funes there was nothing but particulars – and they were virtually immediate particulars.”

(p. 137) Borges’s story isn’t really about memory as much as it is about how we make sense of the world. It’s important to forget things, to ignore the minor differences between similar objects. We recognize that the dog the Funes sees at three-fourteen and the dog that he sees at three-fifteen are the same; Funes does not. Funes dies insane; we, hopefully, do not.

(p. 137) Borges’s story isn’t really about memory as much as it is about how we make sense of the world. It’s important to forget things, to ignore the minor differences between similar objects. We recognize that the dog the Funes sees at three-fourteen and the dog that he sees at three-fifteen are the same; Funes does not. Funes dies insane; we, hopefully, do not.

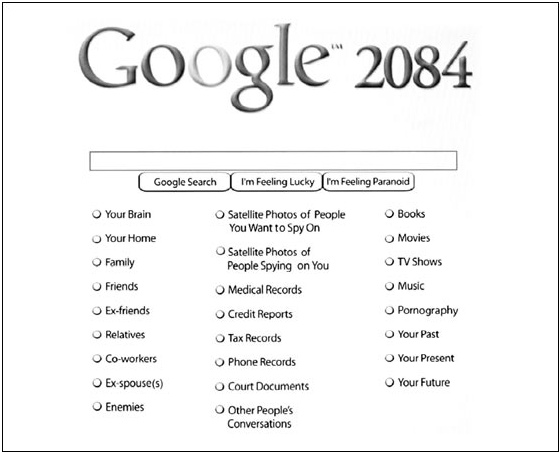

I won’t pretend to be the first to see in the Internet parallels to the all-remembering mind of Funes; a book could be written, if it hasn’t already been, on how Borges invented the Internet. It’s interesting, however, to see that the problems of Funes are increasingly everyone’s problems. As humans, we forget by default; maybe it’s the greatest sign of the Internet’s inhumanity that it remembers. With time things become more obscure on the Internet; you might need to plumb the Wayback Machine at archive.org rather than Google to find a website from 1997. History becomes obscure, but it only very rarely disappears entirely on the Internet.

I won’t pretend to be the first to see in the Internet parallels to the all-remembering mind of Funes; a book could be written, if it hasn’t already been, on how Borges invented the Internet. It’s interesting, however, to see that the problems of Funes are increasingly everyone’s problems. As humans, we forget by default; maybe it’s the greatest sign of the Internet’s inhumanity that it remembers. With time things become more obscure on the Internet; you might need to plumb the Wayback Machine at archive.org rather than Google to find a website from 1997. History becomes obscure, but it only very rarely disappears entirely on the Internet.

A recent working paper by Viktor Mayer-Schoenberger, a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, recognizes the problems of the Internet’s elephantine memory. He suggests pre-emptively dealing with the issues that are sure to spring up in the future by actively building forgetting into the systems that comprise the network. Mayer-Schoenberger envisions that some of this forgetting would be legally enforced: commercial sites might be required to state how long they will keep customer’s information, for example.

A recent working paper by Viktor Mayer-Schoenberger, a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, recognizes the problems of the Internet’s elephantine memory. He suggests pre-emptively dealing with the issues that are sure to spring up in the future by actively building forgetting into the systems that comprise the network. Mayer-Schoenberger envisions that some of this forgetting would be legally enforced: commercial sites might be required to state how long they will keep customer’s information, for example.

It’s an interesting proposal, if firmly in the realm of the theoretical: it’s hard to imagine that the public will be proactive enough about this issue to push the government to take issue any time soon. Give it time, though: in a decade, there will be a generation dealing with embarrassing ten-year-old MySpace photos. Maybe we’ll no longer be embarrassed about our pasts; maybe we won’t trust anything on the Internet at that point; maybe we’ll demand mandatory forgetting so that we don’t all go crazy.

It’s an interesting proposal, if firmly in the realm of the theoretical: it’s hard to imagine that the public will be proactive enough about this issue to push the government to take issue any time soon. Give it time, though: in a decade, there will be a generation dealing with embarrassing ten-year-old MySpace photos. Maybe we’ll no longer be embarrassed about our pasts; maybe we won’t trust anything on the Internet at that point; maybe we’ll demand mandatory forgetting so that we don’t all go crazy.

Images from Hollis Frampton’s film (nostalgia), 1971.