Beginning November 10th, seven women will begin a public conversation in the margins of Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook. The text of the novel and the readers’ conversation will be in a nifty new format designed by Apt Studios in London, similar to, but much more elegant than CommentPress. We’ll put up a preview sometime in October. In the meantime here is a brief bio of the seven readers:

Naomi Alderman grew up in London and attended Oxford University and UEA. Her first novel, Disobedience, was published in nine languages; it was read on BBC radio’s Book at Bedtime and won the Orange Award for New Writers. In 2007, she was named Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year, and one of Waterstones’ 25 Writers for the Future. From 2004 to 2007 Naomi was lead writer on the award-winning alternate reality game Perplex City and in 2008 she wrote the Alice in Storyland game for Penguin’s online We Tell Stories project.

Naomi Alderman grew up in London and attended Oxford University and UEA. Her first novel, Disobedience, was published in nine languages; it was read on BBC radio’s Book at Bedtime and won the Orange Award for New Writers. In 2007, she was named Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year, and one of Waterstones’ 25 Writers for the Future. From 2004 to 2007 Naomi was lead writer on the award-winning alternate reality game Perplex City and in 2008 she wrote the Alice in Storyland game for Penguin’s online We Tell Stories project.

Nona Willis Aronowitz is a freelance writer originally from New York City. She is a political and cultural critic who writes about sex, women, youth culture, and music for numerous publications including The Nation, The New York Observer, The Village Voice, VenusZine, and Salon.com. She currently co-writes a blog called GIRLdrive, the content of which will be in an upcoming book of the same name. GIRLdrive is based on a road trip taken across the United States in order to find out what young women think and feel about feminism, and will be published by Seal Press in Fall 2009. She lives in Chicago.

Nona Willis Aronowitz is a freelance writer originally from New York City. She is a political and cultural critic who writes about sex, women, youth culture, and music for numerous publications including The Nation, The New York Observer, The Village Voice, VenusZine, and Salon.com. She currently co-writes a blog called GIRLdrive, the content of which will be in an upcoming book of the same name. GIRLdrive is based on a road trip taken across the United States in order to find out what young women think and feel about feminism, and will be published by Seal Press in Fall 2009. She lives in Chicago.

Laura Kipnis is a cultural critic and theorist whose most recent books are Against Love: A Polemic and The Female Thing: Dirt, Sex, Envy, Vulnerability (both from Pantheon); her essays have appeared in Slate, Harper’s, Playboy, the Nation, and The New York Times Magazine. Her work has been translated into thirteen languages; she’s received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and Yaddo; and she teaches in the Radio-TV-Film Department at Northwestern University (she is a former video artist). Her next book is called How To Become a Scandal.

Laura Kipnis is a cultural critic and theorist whose most recent books are Against Love: A Polemic and The Female Thing: Dirt, Sex, Envy, Vulnerability (both from Pantheon); her essays have appeared in Slate, Harper’s, Playboy, the Nation, and The New York Times Magazine. Her work has been translated into thirteen languages; she’s received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and Yaddo; and she teaches in the Radio-TV-Film Department at Northwestern University (she is a former video artist). Her next book is called How To Become a Scandal.

Philippa Levine grew up in an upwardly-mobile, left-wing, working-class family in London. She received her doctorate in history during the Thatcher era when academic jobs were thin on the ground so after a brief stint teaching at the University of East Anglia, she took a post-doctoral fellowship in women’s studies in Australia where she combined academic work with radio broadcasting. In 1987 she moved to the US where she has lived since. Her publications include The British Empire, Sunrise to Sunset (2007), Gender and Empire: Oxford History of the British Empire Companion Series (2004) Prostitution, Race and Politics: Policing Venereal Disease in the British Empire (2003). Her current projects include a study of colonial nakedness, and of evolution, eugenics and empire.

Philippa Levine grew up in an upwardly-mobile, left-wing, working-class family in London. She received her doctorate in history during the Thatcher era when academic jobs were thin on the ground so after a brief stint teaching at the University of East Anglia, she took a post-doctoral fellowship in women’s studies in Australia where she combined academic work with radio broadcasting. In 1987 she moved to the US where she has lived since. Her publications include The British Empire, Sunrise to Sunset (2007), Gender and Empire: Oxford History of the British Empire Companion Series (2004) Prostitution, Race and Politics: Policing Venereal Disease in the British Empire (2003). Her current projects include a study of colonial nakedness, and of evolution, eugenics and empire.

Lenelle Moïse is an award-winning “culturally hyphenated pomosexual poet,” playwright and performance artist. She writes jazz-infused, politically-charged performance texts about Haitian-American culture and the intersection of race, class, gender, sexuality. Moïse blogs regularly for Showtime’s OurChart.com. At 20, she co-wrote the screenplay for a Rodrigo Bellot film, Sexual Dependency, which has been screened at dozens of international festivals. Moïse received an MFA in Playwriting from Smith College. Moïse regularly performs her autobiographical one-woman show Womb-Words Thirsting at colleges across the United States and her newest musical Expatriate was produced Off-Broadway at the Culture Project in July 2008 and met with critical acclaim.

Lenelle Moïse is an award-winning “culturally hyphenated pomosexual poet,” playwright and performance artist. She writes jazz-infused, politically-charged performance texts about Haitian-American culture and the intersection of race, class, gender, sexuality. Moïse blogs regularly for Showtime’s OurChart.com. At 20, she co-wrote the screenplay for a Rodrigo Bellot film, Sexual Dependency, which has been screened at dozens of international festivals. Moïse received an MFA in Playwriting from Smith College. Moïse regularly performs her autobiographical one-woman show Womb-Words Thirsting at colleges across the United States and her newest musical Expatriate was produced Off-Broadway at the Culture Project in July 2008 and met with critical acclaim.

Helen Oyeyemi was born in Nigeria in 1984 and raised in London. Her first novel, The Icarus Girl, is about a young girl and her imaginary friend. Her second novel, The Opposite House, is a nominee for the 2008 Hurston/Wright Legacy Award. Her third novel, White is for Witching, will be published in 2009.

Helen Oyeyemi was born in Nigeria in 1984 and raised in London. Her first novel, The Icarus Girl, is about a young girl and her imaginary friend. Her second novel, The Opposite House, is a nominee for the 2008 Hurston/Wright Legacy Award. Her third novel, White is for Witching, will be published in 2009.

Harriet Rubin is best known as the author of The Princessa: Machiavelli for Women, a little bullet of a book on power that is now in its twelfth paperback printing. The book has been published in 27 languages and has been a bestseller in several of them. Rubin currently writes for The NY Times and other publications. She was the founder and publisher of Currency Books/Doubleday, which changed the science and soul of economic thinking. In late Fall 2008, she is launching an on-line publishing program devoted to business, power and leadership.

Harriet Rubin is best known as the author of The Princessa: Machiavelli for Women, a little bullet of a book on power that is now in its twelfth paperback printing. The book has been published in 27 languages and has been a bestseller in several of them. Rubin currently writes for The NY Times and other publications. She was the founder and publisher of Currency Books/Doubleday, which changed the science and soul of economic thinking. In late Fall 2008, she is launching an on-line publishing program devoted to business, power and leadership.

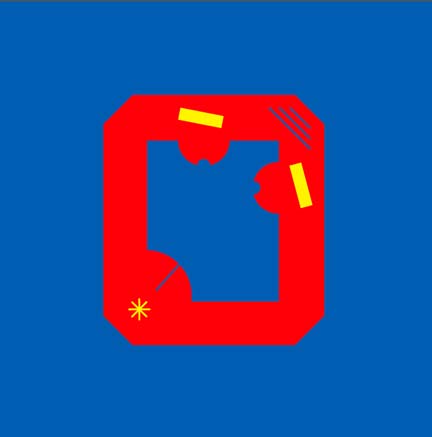

Kenneth Goldsmith has launched a bold, full-throttle investigation into the nature of unpublishability over at Ubu. Introducing Publishing the Unpublishable, Goldsmith asks, “What constitutes an unpublishable work?” Authors sent in works that otherwise would have remained untouched, festering at the bottom of some slush pile. Goldsmith will press onwards until the 100th manuscript is published, and I’ve been keeping my eye on the roll out. There is a 1018-page manuscript (too long!), there are some high school love poems (oh, too juvenile!), and there are several really impressive pieces (the image to the right is from Jeremy Sigler’s Math, a click-through explosion of primary colors). What I really like about Publishing the Unpublishable is that it’s more than an analysis of the wheat&chaff phenomenon:

Kenneth Goldsmith has launched a bold, full-throttle investigation into the nature of unpublishability over at Ubu. Introducing Publishing the Unpublishable, Goldsmith asks, “What constitutes an unpublishable work?” Authors sent in works that otherwise would have remained untouched, festering at the bottom of some slush pile. Goldsmith will press onwards until the 100th manuscript is published, and I’ve been keeping my eye on the roll out. There is a 1018-page manuscript (too long!), there are some high school love poems (oh, too juvenile!), and there are several really impressive pieces (the image to the right is from Jeremy Sigler’s Math, a click-through explosion of primary colors). What I really like about Publishing the Unpublishable is that it’s more than an analysis of the wheat&chaff phenomenon:

Naomi Alderman grew up in London and attended Oxford University and UEA. Her first novel, Disobedience, was published in nine languages; it was read on BBC radio’s Book at Bedtime and won the Orange Award for New Writers. In 2007, she was named Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year, and one of Waterstones’ 25 Writers for the Future. From 2004 to 2007 Naomi was lead writer on the award-winning alternate reality game Perplex City and in 2008 she wrote the Alice in Storyland game for Penguin’s online We Tell Stories project.

Naomi Alderman grew up in London and attended Oxford University and UEA. Her first novel, Disobedience, was published in nine languages; it was read on BBC radio’s Book at Bedtime and won the Orange Award for New Writers. In 2007, she was named Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year, and one of Waterstones’ 25 Writers for the Future. From 2004 to 2007 Naomi was lead writer on the award-winning alternate reality game Perplex City and in 2008 she wrote the Alice in Storyland game for Penguin’s online We Tell Stories project. Nona Willis Aronowitz is a freelance writer originally from New York City. She is a political and cultural critic who writes about sex, women, youth culture, and music for numerous publications including The Nation, The New York Observer, The Village Voice, VenusZine, and Salon.com. She currently co-writes a blog called GIRLdrive, the content of which will be in an upcoming book of the same name. GIRLdrive is based on a road trip taken across the United States in order to find out what young women think and feel about feminism, and will be published by Seal Press in Fall 2009. She lives in Chicago.

Nona Willis Aronowitz is a freelance writer originally from New York City. She is a political and cultural critic who writes about sex, women, youth culture, and music for numerous publications including The Nation, The New York Observer, The Village Voice, VenusZine, and Salon.com. She currently co-writes a blog called GIRLdrive, the content of which will be in an upcoming book of the same name. GIRLdrive is based on a road trip taken across the United States in order to find out what young women think and feel about feminism, and will be published by Seal Press in Fall 2009. She lives in Chicago.  Philippa Levine grew up in an upwardly-mobile, left-wing, working-class family in London. She received her doctorate in history during the Thatcher era when academic jobs were thin on the ground so after a brief stint teaching at the University of East Anglia, she took a post-doctoral fellowship in women’s studies in Australia where she combined academic work with radio broadcasting. In 1987 she moved to the US where she has lived since. Her publications include The British Empire, Sunrise to Sunset (2007), Gender and Empire: Oxford History of the British Empire Companion Series (2004) Prostitution, Race and Politics: Policing Venereal Disease in the British Empire (2003). Her current projects include a study of colonial nakedness, and of evolution, eugenics and empire.

Philippa Levine grew up in an upwardly-mobile, left-wing, working-class family in London. She received her doctorate in history during the Thatcher era when academic jobs were thin on the ground so after a brief stint teaching at the University of East Anglia, she took a post-doctoral fellowship in women’s studies in Australia where she combined academic work with radio broadcasting. In 1987 she moved to the US where she has lived since. Her publications include The British Empire, Sunrise to Sunset (2007), Gender and Empire: Oxford History of the British Empire Companion Series (2004) Prostitution, Race and Politics: Policing Venereal Disease in the British Empire (2003). Her current projects include a study of colonial nakedness, and of evolution, eugenics and empire. Lenelle Moïse is an award-winning “culturally hyphenated pomosexual poet,” playwright and performance artist. She writes jazz-infused, politically-charged performance texts about Haitian-American culture and the intersection of race, class, gender, sexuality. Moïse blogs regularly for Showtime’s OurChart.com. At 20, she co-wrote the screenplay for a Rodrigo Bellot film, Sexual Dependency, which has been screened at dozens of international festivals. Moïse received an MFA in Playwriting from Smith College. Moïse regularly performs her autobiographical one-woman show Womb-Words Thirsting at colleges across the United States and her newest musical Expatriate was produced Off-Broadway at the Culture Project in July 2008 and met with critical acclaim.

Lenelle Moïse is an award-winning “culturally hyphenated pomosexual poet,” playwright and performance artist. She writes jazz-infused, politically-charged performance texts about Haitian-American culture and the intersection of race, class, gender, sexuality. Moïse blogs regularly for Showtime’s OurChart.com. At 20, she co-wrote the screenplay for a Rodrigo Bellot film, Sexual Dependency, which has been screened at dozens of international festivals. Moïse received an MFA in Playwriting from Smith College. Moïse regularly performs her autobiographical one-woman show Womb-Words Thirsting at colleges across the United States and her newest musical Expatriate was produced Off-Broadway at the Culture Project in July 2008 and met with critical acclaim.  Helen Oyeyemi was born in Nigeria in 1984 and raised in London. Her first novel, The Icarus Girl, is about a young girl and her imaginary friend. Her second novel, The Opposite House, is a nominee for the 2008 Hurston/Wright Legacy Award. Her third novel, White is for Witching, will be published in 2009.

Helen Oyeyemi was born in Nigeria in 1984 and raised in London. Her first novel, The Icarus Girl, is about a young girl and her imaginary friend. Her second novel, The Opposite House, is a nominee for the 2008 Hurston/Wright Legacy Award. Her third novel, White is for Witching, will be published in 2009.  Harriet Rubin is best known as the author of The Princessa: Machiavelli for Women, a little bullet of a book on power that is now in its twelfth paperback printing. The book has been published in 27 languages and has been a bestseller in several of them. Rubin currently writes for The NY Times and other publications. She was the founder and publisher of Currency Books/Doubleday, which changed the science and soul of economic thinking. In late Fall 2008, she is launching an on-line publishing program devoted to business, power and leadership.

Harriet Rubin is best known as the author of The Princessa: Machiavelli for Women, a little bullet of a book on power that is now in its twelfth paperback printing. The book has been published in 27 languages and has been a bestseller in several of them. Rubin currently writes for The NY Times and other publications. She was the founder and publisher of Currency Books/Doubleday, which changed the science and soul of economic thinking. In late Fall 2008, she is launching an on-line publishing program devoted to business, power and leadership.