Random House Canada underwrote a series of short videos riffing on Douglas Coupland’s new novel The Gum Thief produced by the slick Toronto studio Crush Inc. These were forwarded to me by Alex Itin, who described watching them as a kind of “cinematic reading.” Watch, you’ll see what he means. There are three basic storylines, each consisting of three clips. This one, from the “Glove Pond” sequence, is particularly clever in its use of old magazines:

All the videos are available here at Crush Inc. Or on Coupland’s YouTube page.

Monthly Archives: December 2007

flight paths: a networked novel

I’d like to draw your attention to an exciting new project: Flight Paths, a networked novel in progress by Kate Pullinger and Chris Joseph, co-authors most recently of the lovely multimedia serial “Inanimate Alice.” The Institute is delighted to be a partner on this experiment (along with the Institute of Creative Technologies at De Montfort University and Arts Council England), which marks our first foray into fiction. A common thread with our past experiments is that this book will involve its readers in the writing process. The story begins:

“I have finished my weekly supermarket shop, stocking up on provisions for my three kids, my husband, our dog and our cat. I push the loaded trolley across the car park, battling to keep its wonky wheels on track. I pop open the boot of my car and then for some reason, I have no idea why, I look up, into the clear blue autumnal sky. And I see him. It takes me a long moment to figure out what I am looking at. He is falling from the sky. A dark mass, growing larger quickly. I let go of the trolley and am dimly aware that it is getting away from me but I can’t move, I am stuck there in the middle of the supermarket car park, watching, as he hurtles toward the earth. I have no idea how long it takes – a few seconds, an entire lifetime – but I stand there holding my breath as the city goes about its business around me until…

He crashes into the roof of my car.”

The car park of Sainsbury’s supermarket in Richmond, southwest London, lies directly beneath one of the main flight paths into Heathrow Airport. Over the last decade, on at least five separate occasions, the bodies of young men have fallen from the sky and landed on or near this car park. All these men were stowaways on flights from the Indian subcontinent who had believed that they could find a way into the cargo hold of an airplane by climbing up into the airplane wheel shaft. It is thought that none could have survived the journey, killed by either the tremendous heat generated by the airplane wheels on the runway, crushed when the landing gear retracts into the plane after take off, or frozen to death once the airplane reaches altitude.

‘Flight Paths’ seeks to explore what happens when lives collide – an airplane stowaway and the fictional suburban London housewife, quoted above. This project will tell their stories.

Through the fiction of these two lives, and the cross-connections and contradictions they represent, a larger story about the way we live today will emerge. The collision between the unknown young man, who will be both memorialised and brought back to life by the piece, and the London woman will provide the focus and force for a piece that will explore asylum, immigration, consumer culture, Islam and the West, as well as the seemingly mundane modern day reality of the supermarket car park itself. This young man’s death/plummet will become a flight, a testament to both his extreme bravery and the tragic symbolism of his chosen route to the West.

Here the authors explain the participatory element:

The initial goal of this project is to create a work of digital fiction, a ‘networked book’, created on and through the internet. The first stage of the project will include a web iteration with, at its heart, this blog, opening up the research process to the outside world, inviting discussion of the large array of issues the project touches on. As well as this, Chris Joseph and Kate Pullinger will create a series of multimedia elements that will illuminate various aspects of the story. This will allow us to invite and encourage user-generated content on this website and any associated sites; we would like to open the project up to allow other writers and artists to contribute texts – both multimedia and more traditional – as well as images, sounds, memories, ideas. At the same time, Kate Pullinger will be writing a print novel that will be a companion piece to the project overall.

We’re very curious/excited to see how this develops. Go explore the site, which is just a preliminary framework right now, and get involved. And please spread the word to other potential reader/paticipants. A chance to play a part in a new kind of story.

10 types of publication

In my other life, in the world of web startups, I often have to contend with people who are steadfastly convinced that everyone lives in the technical future. In this world, everyone blogs, knows what an RSS feed does, has an opinion on Yahoo! Pipes, and will be able to tell me why this list of characterizations of ‘the technical future’ is already obsolete. And yet Chris, in his introductory post as if:book’s co-director, remarks on ‘how so much reading promotion cuts literature off from other media, as if anyone still lives solely in a ‘world of books’.

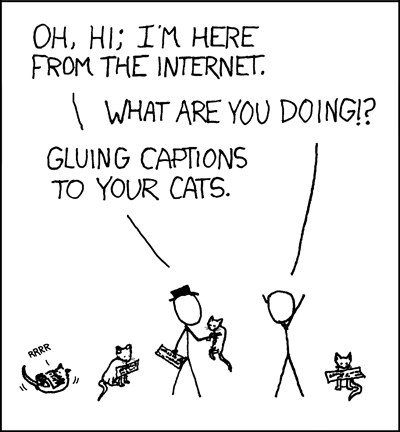

This strange inability of two worlds to acknowledge one another reminds me of a classic geek joke:

As Chris pointed out, we all exist in a world of multiple media outlets, which cross-fertilise vigoriously. But what have analog and digital to say about one another? At the first if:book:group meeting in London, Kate Pullinger remarked on how despite writing both print and digital fiction, her last print novel barely even mentioned the internet. Noga Applebaum pointed out how she’s devoted an entire PhD thesis to the overwhelmingly negative portrayals of technology in children’s fiction. Digital technology seems to appear in analog media only in cursory, fantastical or critical portrayals. Meanwhile, the ‘content’ of analog media is absorbed (digitized) into this brave new world, whose capacity for infinite reproducibility creates exciting new opportunities to see text in motion while causing a kerfuffle with its touted potential irreversibly to disrupt the established modus vivendi.

The relation between the worlds appears strangely asymmetrical. Print is at best a source of ‘content’, a sweet and outmoded ‘original’, sometimes a fetish. Even the lexicon reinforces this.

In a recent meeting, someone spotted me doodling, captured some doodle with his ‘analog to digital converter’ (ie a camera phone), and mailed it around. But what is it called if this image, thus digitized, is rendered in paper again? Is there a word for that? ‘Analogized’ doesn’t sound right (though I’m going to stick with it for the moment, faute de mieux).

The lack of a functioning concept of ‘analogization’ implies that we don’t need one, that there are 10 ways of publishing: those exploring, or eventually destined for digitization, and those destined for the scrap heap – or at best an obscure warehouse on the outskirts of asprawling megalopolis.

But is this true?

Geeks have a solid history of taking internet references back out into meatspace (pleasingly, the title of the above graphic, from the wonderful xkcd.com, is ‘in_ur_reality.png’). But it takes truly mass adoption of the internet to turn re-analogization of internet culture from being a nerdy in-joke to something you might see at Hallowe’en on the New York subway:

Rebecca Lossin, in a thoughtful comment on Chris’ recent post about Blake, remarks on “…something that while acknowledged by champions of electronic formats, is not dealt with very thoroughly. Books still seem more important than blogs. Big books seem even more important than little books.” Books, especially big books, are still associated with authority, thanks – she continues – to “…an extremely important aspect of reading: the acculturated reader.”

“The acculturated reader” sums succinctly what I was gesturing at when I posted about a messageboardful of average internet users debating the cultural significance of bookshelves. These readers, acculturated to the nexus of significations traditionally ascribed to physical books, navigate these significations in daily life but are additionally literate in internet discourse. Unlike many commentators on the apparent binary in play here, they see no competition or contradiction at all.

My introductory post on this blog was about how, as an aspiring (print) writer, I fell accidentally in love with the internet. As I explored the medium, my interest in print publication waned, and my suspicion grew that for a writer who wants her writing to change the world, there are more effective, instant-gratification – and digital – media out there that scratch the verbal itch without requiring the writer to receive 1,005,678 rejection letters and starve in obscurity for decades first (well, not the rejection letters anyway).

But since cocking that snook at the slow-moving world of print, I’ve spent the year pondering the relation between analog and digital writing. And I’ve concluded that there are more than 10 ways of publishing; that they are not in opposition to one another; and that a new generation of ‘acculturated readers’ is emerging that takes on board both the cultural significance of books and also the affordances of the internet, uses each tactically according to the kinds of writing/reading each facilitates best, and is beginning to explore the movement of content not just from analog to digital but also back to analog again.

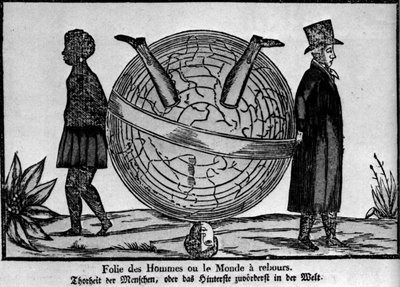

So here’s a beautiful example of a symbiosis of print and digital media, come full circle. BibliOdyssey is a gloriously eccentric blog dedicated to obscure, intriguing, unusual or visually stunning print art. Today I learned that the pick of BibliOdyssey is to be published as a physical book.

This trajectory – books that originate in blogs – pulls away from the narrative of ineluctable digitization that preoccupies much of the debate around the relation between print and the internet. Of course, it’s not new (remember Jessica Cutler?). But the BibliOdyssey book narrative is especially delicious (should that be del.icio.us?), as the material in the book consists of print images that were digitized, uploaded into scores of obscure online archives, collected by the mysterious PK on the BibliOdyssey blog and then re-analogized as a book. It’s an anthology of content that has come on a strange journey from print, through digitization and back to print again. So it’s possible to observe these images in multiple cultural contexts and investigate the response of ‘the acculturated reader’ in each. The question is: what does the material gain or lose in which medium?

The post-bit atom fascination of an ‘original’, a rare object, is powerful. But once digitized and uploaded into public-access archives (however byzantine, in practice, these are to navigate) this layer of interest is stripped, and value must be found elsewhere. Quirkiness; novelty; art-historical interest; the fleeting delight of stumbling upon something visually stunning whilst idly browsing. But the infinite reproducibility of the image means that it’s only of transactional value in a momentary, conversational sense: I send you that link to an amusing engraving, and our relationship is strengthened if you grasp why I sent that particular one and respond in kind.

The overall value of the blog, then, is in its function as dense repository of links that can be used thus. So what is the value of the images again once re-analogized? In the case of BibliOdyssey, it’s a beautiful coffee-table book, delightful in itself and that archly foregrounds its status as hip-to-the-internets.

Perhaps, a century down the line, when climate change has killed off the internet and we’re all living in candlelit huts, it’ll be a scarce and precious resource hinting at times gone by. But however the future pans out, right now it’s both evidence of the dialogic relation of analog and digital media, and also a palimpsest offering glimpses of the shifting signification of cultural content when published in different forms. Texts, images or collections of such aren’t just sitting there waiting to be digitized: once digitized, they take on new life, and increasingly creep back out into the analog world to glue captions to your cats.

generation gap?

A pair of important posts, one by Siva Vaidhyanathan and one by Henry Jenkins, call for an end to generationally divisive rhetoric like “digital immigrants” and “digital natives.”

From Siva:

Partly, I resist such talk because I don’t think that “generations” are meaningful social categories. Talking about “Generation X” as if there were some discernable unifying traits or experiences that all people born between 1964 and pick a year after 1974 is about as useful as saying that all Capricorns share some trait or experience. Yes, today one-twelfth of the world will “experience trouble at work but satisfaction in love.” Right.

Invoking generations invariably demands an exclusive focus on people of wealth and means, because they get to express their preferences (for music, clothes, electronics, etc.) in ways that are easy to count. It always excludes immigrants, not to mention those born beyond the borders of the United States. And it excludes anyone on the margins of mainstream consumer or cultural behavior.

In the case of the “digital generation,” the class, ethnic, and geographic biases could not be more obvious.

From Jenkins:

In reality, whether we are talking about games or fan culture or any of the other forms of expression which most often get associated with digital natives, we are talking about forms of cultural expression that involve at least as many adults as youth. Fan culture can trace its history back to the early part of the 20th century; the average gamer is in their twenties and thirties. These are spaces where adults and young people interact with each other in ways that are radically different from the fixed generational hierarchies affiliated with school, church, or the family. They are spaces where adults and young people can at least sometimes approach each other as equals, can learn from each other, can interact together in new terms, even if there’s a growing tendency to pathologize any contact on line between adults and youth outside of those familiar structures.

As long as we divide the world into digital natives and immigrants, we won’t be able to talk meaningfully about the kinds of sharing that occurs between adults and children and we won’t be able to imagine other ways that adults can interact with youth outside of these cultural divides. What once seemed to be a powerful tool for rethinking old assumptions about what kinds of educational experiences or skills were valuable, which was what excited me about Prensky’s original formulation [pdf], now becomes a rhetorical device that short circuits thinking about meaningful collaboration across the generations.

kindle maths 101

Chatting with someone from Random House’s digital division on the day of the Kindle release, I suggested that dramatic price cuts on e-editions -? in other words, finally acknowledging that digital copies aren’t worth as much (especially when they come corseted in DRM) as physical hard copies -? might be the crucial adjustment needed to at last blow open the digital book market. It seemed like a no-brainer to me that Amazon was charging way too much for its e-books (not to mention the Kindle itself). But upon closer inspection, it clearly doesn’t add up that way. Tim O’Reilly explains why:

…the idea that there’s sufficient unmet demand to justify radical price cuts is totally wrongheaded. Unlike music, which is quickly consumed (a song takes 3 to 4 minutes to listen to, and price elasticity does have an impact on whether you try a new song or listen to an old one again), many types of books require a substantial time commitment, and having more books available more cheaply doesn’t mean any more books read. Regular readers already often have huge piles of unread books, as we end up buying more than we have time for. Time, not price, is the limiting factor.

Even assuming the rosiest of scenarios, Kindle readers are going to be a subset of an already limited audience for books. Unless some hitherto untapped reader demographic comes out of the woodwork, gets excited about e-books, buys Kindles, and then significantly surpasses the average human capacity for book consumption, I fail to see how enough books could be sold to recoup costs and still keep prices low. And without lower prices, I don’t see a huge number of people going the Kindle route in the first place. And there’s the rub.

Even if you were to go as far as selling books like songs on iTunes at 99 cents a pop, it seems highly unlikely that people would be induced to buy a significantly greater number of books than they already are. There’s only so much a person can read. The iPod solved a problem for music listeners: carrying around all that music to play on your Disc or Walkman was a major pain. So a hard drive with earphones made a great deal of sense. It shouldn’t be assumed that readers have the same problem (spine-crushing textbook-stuffed backpacks notwithstanding). Do we really need an iPod for books?

UPDATE: Through subsequent discussion both here and off the blog, I’ve since come around 360 back to my original hunch. See comment.

We might, maybe (putting aside for the moment objections to the ultra-proprietary nature of the Kindle), if Amazon were to abandon the per copy idea altogether and go for a subscription model. (I’m just thinking out loud here -? tell me how you’d adjust this.) Let’s say 40 bucks a month for full online access to the entire Amazon digital library, along with every major newspaper, magazine and blog. You’d have the basic cable option: all books accessible and searchable in full, as well as popular feedback functions like reviews and Listmania. If you want to mark a book up, share notes with other readers, clip quotes, save an offline copy, you could go “premium” for a buck or two per title (not unlike the current Upgrade option, although cheaper). Certain blockbuster titles or fancy multimedia pieces (once the Kindle’s screen improves) might be premium access only -? like HBO or Showtime. Amazon could market other services such as book groups, networked classroom editions, book disaggregation for custom assembled print-on-demand editions or course packs.

This approach reconceives books as services, or channels, rather than as objects. The Kindle would be a gateway into a vast library that you can roam about freely, with access not only to books but to all the useful contextual material contributed by readers. Piracy isn’t a problem since the system is totally locked down and you can only access it on a Kindle through Amazon’s Whispernet. Revenues could be shared with publishers proportionately to traffic on individual titles. DRM and all the other insults that go hand in hand with trying to manage digital media like physical objects simply melt away.

* * * * *

On a related note, Nick Carr talks about how the Kindle, despite its many flaws, suggests a post-Web2.0 paradigm for hardware:

If the Kindle is flawed as a window onto literature, it offers a pretty clear view onto the future of appliances. It shows that we’re rapidly approaching the time when centrally stored and managed software and data are seamlessly integrated into consumer appliances – all sorts of appliances.

The problem with “Web 2.0,” as a concept, is that it constrains innovation by perpetuating the assumption that the web is accessed through computing devices, whether PCs or smartphones or game consoles. As broadband, storage, and computing get ever cheaper, that assumption will be rendered obsolete. The internet won’t be so much a destination as a feature, incorporated into all sorts of different goods in all sorts of different ways. The next great wave in internet innovation, in other words, won’t be about creating sites on the World Wide Web; it will be about figuring out creative ways to deploy the capabilities of the World Wide Computer through both traditional and new physical products, with, from the user’s point of view, “no computer or special software required.”

That the Kindle even suggests these ideas signals a major advance over its competitors -? the doomed Sony Reader and the parade of failed devices that came before. What Amazon ought to be shooting for, however, (and almost is) is not an iPod for reading -? a digital knapsack stuffed with individual e-books -? but rather an interface to a networked library.

gained the world and lost your audience

A passage from Gabriel Josipovici‘s elegant novel Everything Passes gave me pause on the train yesterday morning. Here, Josipovici’s protagonist argues for reading Rabelais as the first modern writer:

—Rabelais, he says, is the first writer of the age of print. Just as Luther is the last writer of the manuscript age. Of course, he says, without print Luther would have remained a simple heretical monk. Print, he says, scooping up the froth in his cup, made Luther the power he became, but essentially he was a preacher, not a writer. He knew his audience and wrote for it. Rabelais, though, he says, sucking his spoon, understood what this new miracle of print meant for the writer. It meant you had gained the world and lost your audience. You no longer knew who was reading you or why. You no longer knew who you were writing for or even why you were writing. Rabelais, he says, raged at this and laughed at it and relished it, all at the same time.

[ . . . . ]

—Rabelais, he says, is the first author in history to find the idea of authority ridiculous.

She looks at him over her coffee-cup. —Ridiculous? she says.—Of course, he says. For one thing he no longer felt he belonged to any tradition that could support or guide him. He could admire Virgil and Homer, but what had they to do with him? Homer was the bard of the community. He sang about the past and made it present to those who listened. Virgil, to the satisfaction of the Emperor Augustus, made himself the bard of the new Roman Empire. He wove its myths about the past together in heart-stopping verse and so gave legitimacy to the colonisation and subjugation of a large part of the peninsula. But Rabelais? If enough people bought his books, he could make a living out of writing. But he was the spokesman of no one but himself. And that meant that his role was inherently absurd. No one had called him. Not God. Not the Muses. Not the monarch. Not the local community. He was alone in his room, scribbling away, and then these scribbles were transformed into print and read by thousands of people whom he’d never set eyes on and who had never set eyes on him, people in all walks of life, reading him in the solitude of their rooms.

( pp. 17–19.) It’s worth quoting at length because Josipovici’s prose opens so many questions: today, we potentially find ourselves in a situation where authority and the audience could potentially be radically rearranged, maybe as much so as when Rabelais was writing.

welcome, sebastian mary! (it’s official)

We are very happy to welcome Sebastian Mary Harrington onto the “official” Institute masthead. This is long overdue, and merely formalizes what is already without question one of our most important and well established partnerships. But formalized it is. And we’re damn pleased.

It all started two Octobers ago with a casual comment on a post about iPods and reading. An email exchange ensued and before we knew it sMary was blogging away, quickly carving out her place as what you might call our “new online literary forms correspondent.” For over a year now she’s been writing some of the best coverage to be found anywhere on alternative reality games (ARGs), as well as brilliant speculative essays on the future shape of authorship, copyright and the economics of publishing. (She’s also become a dear friend.) I wonder if it’s happened before: a random blog comment leading to a paid writing gig? It’s a good story in itself, and sort of captures why blogging is such an important part of our work.

Here’s little sampler of her if:book portfolio (running newest to oldest):

- “books and the man i sing”: parts one, two and three

- “of babies and bathwater”

- “it’s multimedia, jim, but not as we know it”

- “pay attention to the dance”

- “give away the content and sell the thing”

- net native stories are already here: so are the vultures”

- “do bloggers dream of electrifying text?”

Once again, we’re delighted sMary will be officially working with us for part of every month, continuing to deliver her sharp insights and humor here on if:book, and taking part in some of our emerging activities on the London scene.

This is also probably a good time to say a bit more about sMary’s other endeavors. In addition to her work with the Institute, she’s co-founder of the UK web startup School of Everything (chosen by Seedcamp as one of Europe’s hottest startups of 2007) and co-founder and creative director of the cult London art event ARTHOUSEPARTY. You can find out a bit more on our staff page.

Another warm welcome to sMary. You’ll no doubt be hearing more from her soon.

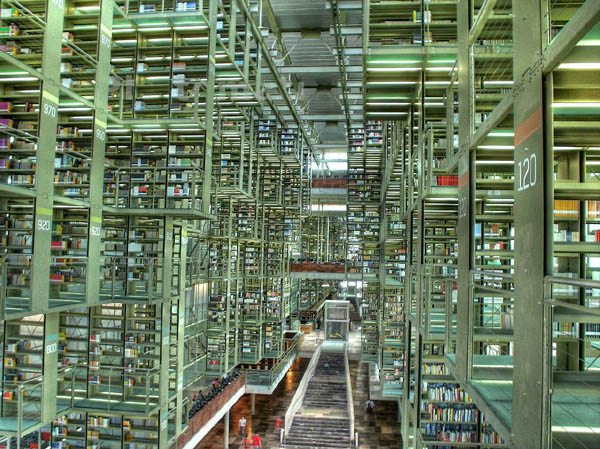

the tomb of the book

“Vista de la Biblioteca Vasconcelos” by Eneas, on Flickr

A lovely meditation at BLDG Blog on the architecture of storage facilities for unwanted books. Speaks volumes (as it were) to the anxiety of obsolescence that keeps librarians up at night -? the thought of libraries themselves becoming tombs.

…a relatively random piece of 100-year old legislation – dealing with copyright law, of all things – has begun to exhibit architectural effects.

These architectural effects include the production of huge warehouses in the damp commuter belts of outer London. These aren’t libraries, of course; they’re stockpiles. Text bunkers.

…Perhaps it will take some future moment of cultural archaeology to break into these places, spelunking back into the literate past, to find well-tempered rooms still humming at 50ºF, humidity-free, where the past is refrigerated and Shakespeare’s name can still be recognized on the spines of books.

a grant for Sophie from The Macarthur Foundation

We are very happy to announce that the Macarthur Foundation has just provided a $400,000 grant which will ensure the release of version 1.0 of Sophie in February. Yay!

talking of poets and sparkles

‘The cast of mind which searches, which questions, which dissents, has a great history. Each society has given it its own form: religious, literary. scientific. Much of the strength of Blake derives from the twofold form which dissent took in his time: rational and inspired… The history of dissent is not yet ended; it does not end. Men die, and societies die. They are not more lasting for being without dissent, they are more brittle: for they are purposeless, because they deny themselves a future.’

So writes Charles Bronowski in his book on William Blake, A Man Without a Mask, quoted by Shirley Dent of the Institute of Ideas in an article on the anniversary of Blake’s birth 250 years ago.

Brilliant, belligerent, barmy Blake has been claimed as a figurehead by all kinds of hippies and politicoes over the years, and was recently cited as ‘The Godfather of Psychogeography‘ by Ian Sinclair for, among other things, seeing angels in the trees of Peckham Rye and the new Jerusalem in leafy north London:

“The fields from Islington to Maylebone,

To Primrose Hill and Saint John’s Wood:

Were builded over with pillars of gold,

Are there Jerusalems pillars stood.”

(This quote from Jerusalem features in Merlin Coverley’s excellent guide to Psychogeography which includes city strollers from Defoe and Poe to Debord and Will Self).

William Blake, the man who wandered through the charter’d streets of London finding in the face of every passerby ‘marks of weakness, marks of woe’, who engraved and painted his own books of poems, selling his songs on subscription (or failing to sell them), would have made one hell of a blogger too. I imagine him mashing up maps of Hampstead with his personal mythology, forging a new kind of book on the anvil of his laptop, engaging his community of readers in fervent debate, plying them with animations of innocence and experience.