October 20, 2005

The Beethoven's Ninth Symphony CD Companion

"Music appreciation" is a much-maligned scholarly subset -- a throwaway course at university for saps and jocks, "clapping for credit" to the hackneyed strains of Vivaldi's Four Seasons or The Brandenburg Concerti. But anyone who has taken one of these courses with a talented teacher knows that the results can be life-changing. Like great popular science writers Stephen Jay Gould or Richard Feynman, who unlocked the secrets of nature and mathematics for a general audience, a great introductory music course can teach the art of listening to people bound for various non-musical futures. Wherever they end up, their ear is forever wiser.

A great teacher provides context, weaves a narrative, and helps you get inside the mechanics and mathematics of the music. It's a process of deconstructing the complex organism that is the orchestra -- picking it apart, leading you through its components, and training your ear to put it back together again. The best music history lectures I attended in college involved the professor running back and forth between the stereo system, the podium and the blackboard. Occasionally he'd dash over to piano and hammer out a few bars. Sometimes, if we were examining a chamber work, he'd invite a trio or quartet from the neighboring conservatory, stopping them and starting them like a DJ, going over certain passages intensively. I would sit back and listen, sometimes taking notes, as new pieces of the puzzle were introduced. Later, I would immerse myself in the recordings and connect the dots from what I'd learned.

In 1989, the Voyager Company produced what is generally considered to be the first interactive electronic publication: The Beethoven's Ninth Symphony CD Companion. Developed in Apple's HyperCard, it was the first CD-ROM publication to wed a computer program to an audio disk. Most important, it was the combination in one work of recording, text, and inspired instruction -- all the tools needed to unlock the secrets of the music.

If the CD-ROM was a bottle, than the genie -- the inspired instructor, the individual creative voice that ties it all together -- was Robert Winter, a pioneering music scholar, pianist and author at UCLA who went on to develop two more titles with Voyager in this series, including Stravinsky's Rite of Spring (view demo) and Dvorak's Symphony No. 9 "From the New World". The Beethoven stack is built around an excellent recording of the Ninth Symphony by the Vienna Philharmonic. A single-page overview provides a menu of the symphony, allowing the reader to jump to any section instantaneously.

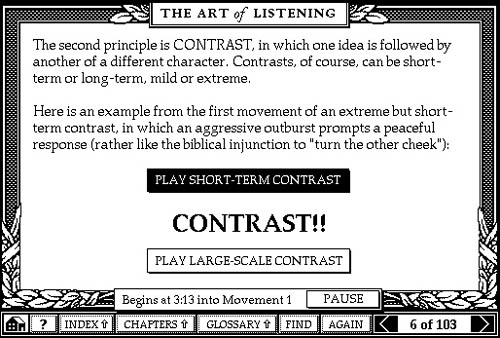

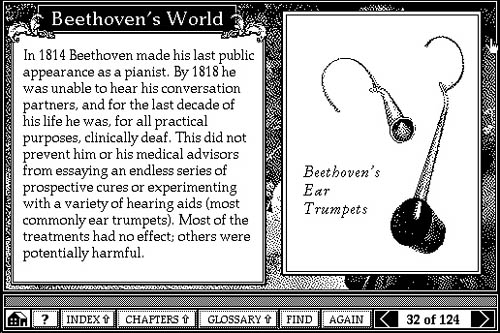

In other sections, Winter ties in basic theory, counting out sections of the music, explaining shifts in rhythm (especially helpful with Stravinsky). He also provides ample textual materials going in depth on various musical conventions and concepts, and providing a rich sense of Beethoven's world and the cultural cosmos in which he worked. There is even a quiz section to help give you a sense of how your listening has improved.

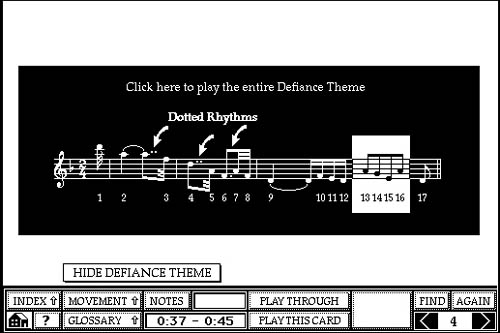

But the central element of the CD-ROM is close reading. As you listen, a cursor takes you through the score measure by measure with a running a commentary from Winter -- identifying themes, elucidating passages, and drawing attention to the effects of particular instruments.

From a design standpoint, this is the major breakthrough of Beethoven's Ninth: the tying of text to specific sections of music in "time-based events."

Putting the teacher inside the book infuses it with the dynamism and precision of a live lecture. It also expands our conception of what it means to illustrate a page. We know how to handle still images or diagrams -- these are relatively easy to arrange in relation to the main flow of the argument. But for time-based media such as music and film -- or in works for which music or film provides the "spine" of the book -- the rhetorical devices must be updated. It's no problem in a live lecture. The professor can simply talk over the symphony or film -- pausing, replaying, emphasizing certain sections. But how do you get this inside the book? How do you write a critical work on time-based media that is not alienated from its subject? Beethoven's Ninth was the program that first suggested a solution.

Posted by ben vershbow at 6:50 PM

September 21, 2005

The Voyager Macbeth: An Expanded Critical Edition

Remember HyperCard? Apple's original, card-based graphical application made it possible to craft book-like works out of a database structure, allowing for multiple trajectories through the text and the intermingling of graphics and motion media. (Smackerel.net provides a nice refresher on "When Multimedia Was Black & White") Many of the works built in HyperCard have taken on the status of relics, but the best of them never fail to impress, reminding us that some of the biggest conceptual leaps in digital media were made over ten years ago, and in many ways remain unsurpassed.

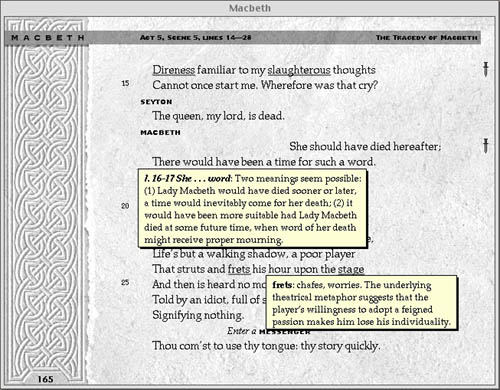

The Voyager Macbeth is a HyperCard-based CD-ROM that blew the lid off what seemed possible in a critical edition of a literary text (view demo). The disc is structured around the 1993 New Cambridge edition of the play, introduced by David Rodes, and thoroughly annotated by A.C. Braunmuller - both leading Shakespeare scholars and professors at UCLA. Producer and chief programmer Michael Cohen describes it as "a rich, immersive, book-like experience" - "a layered format." The text can be read, searched, listened to, watched, and even recited out loud with a pre-recorded actor reading opposite (a feature called "Macbeth Karaoke"). Trevor Nunn's seminal 1976 Royal Shakespeare Company production with Ian McKellan and Judy Dench supplies a complete audio track that can be brought into action instantly with a mouse click, beginning on any desired line. One can read the entire text this way, the pages turning automatically, with the impeccable cast of the RSC bringing it to life like a radio play.

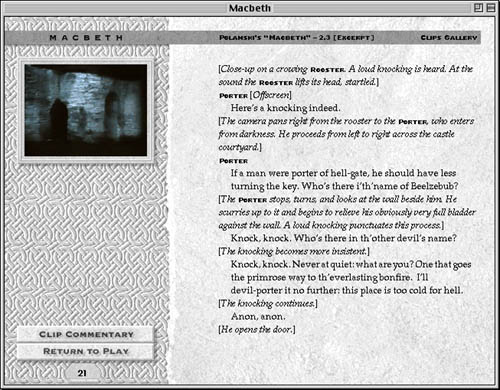

Each page is rich with annotations, which can be summoned as pop-up windows by clicking on underlined words or passages. You can also click on little dagger icons in the margins that provide further context or tie a speech to other moments and motifs in the play, or little film strip icons that indicate video clips are available. Here opens another region of this vast edition. The editors have provided lengthy clips, with commentary, from three of the greatest screen adaptations of Shakespeare's tragedy - Orson Welles' Macbeth (1948), Akira Kurosawa's Throne of Blood (1957), and Roman Polanski's The Tragedy of Macbeth (1971) - all of which can be viewed (albeit on a small screen - this would be different now) within the book.

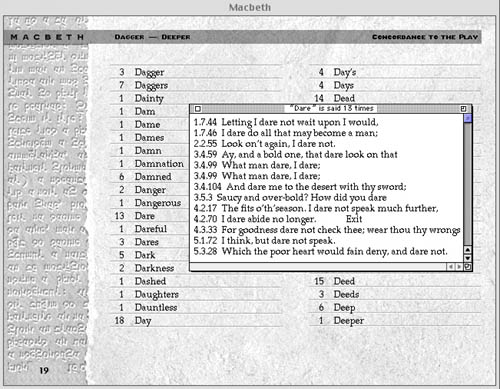

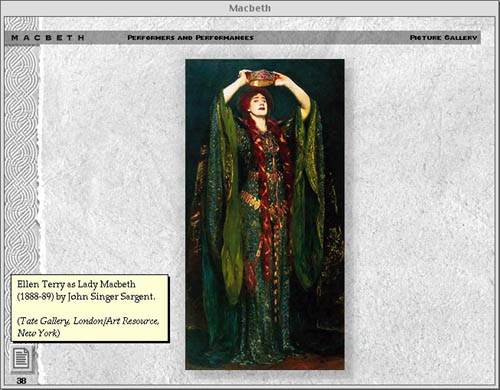

Other assets that expand the universe of the play and deepen the reader's investigation include a lengthy introduction by Professor Rodes, a library of critical essays, detailed background on Shakespeare's life and Elizabethan context, excerpts from the Holinshed Chronicles from which the play is drawn, a large archive of images documenting Macbeth's influence on western culture and various stage productions through the centuries, and important analytical tools such as character profiles, scene summaries and analysis, a full text concordance, and collation with other versions of the play (indispensable in Shakespeare scholarship). The only thing lacking, which could no doubt be solved if The Voyager Macbeth were being remade today, is the ability to write one's own notes in the text and to mark specific sections.

Chatting with Michael Cohen, I asked why so few electronic works of this caliber have been produced since the mid 90s. He pointed to the world wide web, which came into public use just as CD-ROMs were hitting their stride, and had the unfortunate effect of all but halting this period of development. "The web enables the making of small things." To some extent these things can be woven together, but the web is fundamentally not good at providing a center, which is essential for serious scholarship and textual analysis. "There is a place," he continued, "for well-considered, architected book-like materials." These materials should be able to weave together rich media and text in a way that paper cannot, yet still retain the focus and coherence of bounded print materials.

"But," I asked, "isn't the network something that should be used productively in these 'book-like' objects? There are resources on the web that can be of use, not to mention opportunities to communicate and work collaboratively with other students through the book. 'Macbeth Karaoke,' for instance, could incorporate a live chat tool that would make it possible to read with scene partners over the web." Or, students could interpret the text collaboratively with the Ivanhoe game (also profiled on nexttext). He agreed that the network should be fully employed, and that hopefully, tools would be developed that enabled the relatively easy production of bounded, media-rich works that can piggy-back on the web and draw on all the affordances of networked space. This suggests a vision of the future textbook that exists comfortably in the context of the web, and yet is not entirely of the web. Like a boat in the stream, it retains all the rigors and cohesion of the material world.

Cohen sees great potential in the recent increase in high school and university programs that provide laptops to every student. They'll need to load something on to that equipment, something more disciplined than a web browser. When you have unbroken access to your own machine, you can dive deeper - perhaps there is the potential for rich, immersive educational materials to make an entrance in programs like these.

Posted by ben vershbow at 8:17 AM