« Virtual Village Allows Virtual "Fieldwork" | Main | "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity" and "Imaging The French Revolution:" Two Generations of Digital Texts »

December 9, 2005

Online Science For The Wired Classroom: The "Disease Spread" Gizmo from Explore Learning

When considering the ways in which born-digital learning materials might replace conventional textbooks, it's important to think about how digital material might change the notion of what a textbook can be - for example, replacing the idea of a "one size fits all" standard classroom text with a number of smaller, atomized learning modules. The six-year-old company Explore Learning has produced over 400 such interactive modules, which they call "gizmos," for use in math and science classrooms. Each gizmo is a brief, animated Shockwave presentation, accompanied by a control panel, a series of assessment questions, and an "exploration guide" that suggests a series of experiments for students. Available through subscription, Explore Learning gizmos have won e-learning awards and recognition from the National Science Foundation, and are widely used in schools around the country.

Browsing through the gizmos (the company allows the user a 30-day free trial before asking them to purchase a subscription), I found them fairly sophisticated both in conceptualization and design. Explore Learning has managed to avoid the hypercolorful "edutainment software" approach of some K-12 digital instructional material, but they've also made their experiments visually interesting enough to capture the often variable attention of high school science students. The selection encompasses most math and science requirements for grades 6 through 12 (and early collecge): algebra, geometry, physics, data analysis, biology, chemistry, and earth and space science. There are gizmos which reveal the structure of snowflakes, teach about RNA and protein synthesis, and explore the interior surface of the Earth.

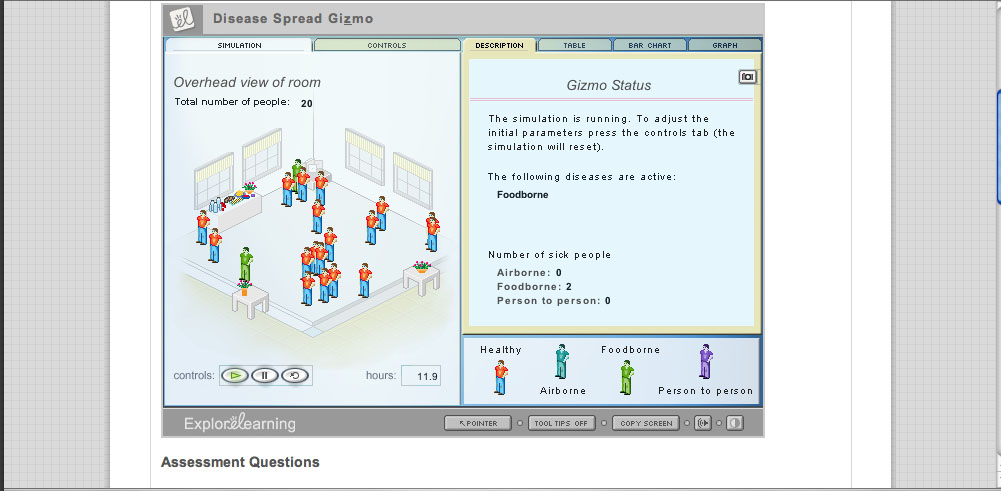

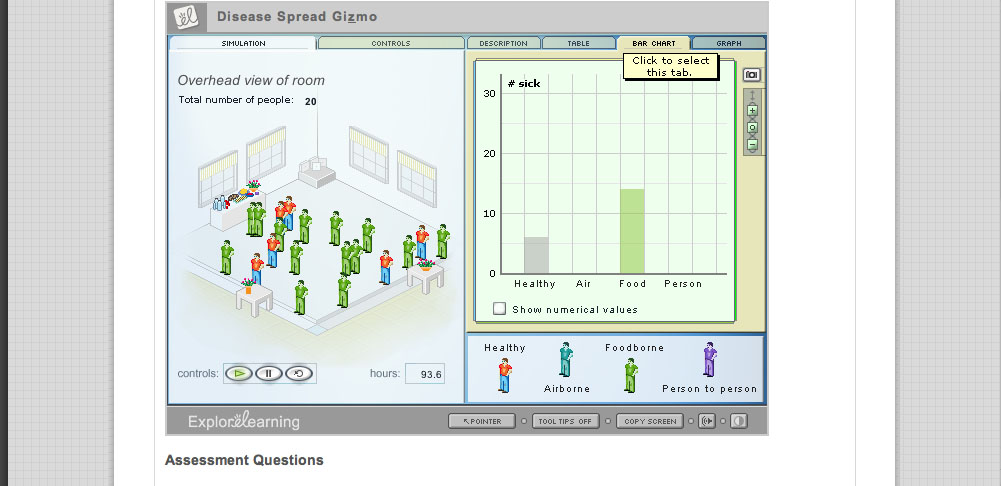

What makes gizmos pedagogically valuable is that they are not simply demonstrations of scientific principles, but experiments in which students are asked to collect data and report results. One such experiment is the "Disease Spread" gizmo, a relatively straightforward module intended for life sciences classrooms in grades 6 thought 8. "Disease Spread" teaches about airborne, food-born, and person-to-person transmission of disease. The gizmo is centered around a "simulation room" containing an adjustable number of persons and a buffet table filled with food. A s shown in the image above, red figures are healthy, while blue figures are infected with airborne disease, green with foodborne diseases, and purple with diseases obtained through person-to-person contact. Using the control panel, students select how many people are in the room, and study the patterns of disease tranmission by consulting tables and by looking at the figures in the room to see if they have changed color. The image below shows the effects of foodborne disease transmission over a brief interval of time:

After the simulation has run through on its own, the instruction sheet linked to the gizmo asks the student to manipulate the controls on the simulation in order to answer research questions. One question focuses on whether multiple methods of contagion allow a disease to spread more quickly:

If the same disease could spread through both airborne and foodborne transmission, would it spread more quickly or more slowly than if it could only spread by one of these means? Think about your answer, and then check it by running another trial of the simulation with both Airborne and Foodborne turned on under Allowed diseases on the Controls tab. Explain how the simulation's results support your answer.

I found the "disease transmission" gizmo to be a simple and effective teaching tool; I could easily see it work in a middle school biology or health classrom. I did wonder, however, whether the gizmo, oversimplified the idea of "person to person" disease contact. The explanatory text claims that "some diseases can spread through physical contact between healthy and infected people. For example, a person infected with one of these diseases might accidentally pass on his or her pathogens to healthy people by shaking their hands or patting them on the back."

In the absence of a other information - and given the proliferation of misinformation about disease - I'm concerned that such a simplified approach might lead middle school students to believe that diseases such as HIV/AIDS could be spread through handshakes or pats on the back. This suggests, in turn, the need for teachers to insert gizmos inside a balanced curriculum that goes beyond the included exploration guides to anticipate and compensate for what the gizmos can't do. An overreliance on atomized tools like gizmos may make for a lively classroom, but it could also potentially underemphasize the "connecting the dots" or thinking deeply about an issue. Learning aids have been around for decades, but the success of Explore Learning and Brainpop suggests that teachers are increasingly relying on online aids both in and out of the classroom. It's important to consider whether this has produced a structural change in math and science pedagogy that needs to be assessed beyond thinking through whether these online modules teach the lessons they promise to teach.

Finally, it's interesting to note that over the past year, explore learning was acquired by Proquest, a leading provider of online information resources that hasn't until recently made inroads into the world of K-12. The fact that Proquest -- instead of a K-12 publishing house -- is now in charge of determining the direction of explore learning suggests that the company will continue as an archive of indexed and searchable learning materials, rather than exploring how various groups of gizmos might be woven into a multimedia math or science text.

Posted by lisa lynch at December 9, 2005 3:53 PM