« August 2005 | Main | October 2005 »

September 30, 2005

The Textbook Behind the Textbook: Western Civilization Course Portfolio

More than just a replacement for its print predecessor, the electronic textbook introduces new formats that help teachers improve course design and student learning. The public nature of online books can help transform the closed, teacher-centered, world of the lecture hall allowing students, teachers, and peer reviewers to examine and comment on all aspects of the course.

Dr. Mills Kelly's online textbook "Western Civilization" and the companion

Course Portfolio are an excellent case in point. The course portfolio is an open, running narrative of the course structure, goals, progress, conclusions, and, perhaps most importantly, the portfolio is "open to public scrutiny and is available to other members of the scholarly community for their use and elaboration." The course portfolio is the learning tool for teachers. It is a kind of textbook behind the textbook. Dr. Kelly used this twin-set (course portfolio and digital textbook) to answer the question, "how does the introduction of hypermedia into a history course influence student learning in that course?"

Dr. Kelly's creation of an online textbook and a course portfolio was part of an evolution in his thinking about the structure of the course itself. Over the years, he had become increasingly unhappy with the "coverage model introductory history survey course." Students, Dr. Kelly notes, have grown even more impatient with this format.

In survey after survey that I have conducted over the years, they tell me that the coverage model encourages the memorize-regurgitate-forget model of learning, but that a more focused approach helps them to think more carefully and to arrive at a deeper understanding of the material they are considering. In my surveys this year, fewer than 10% of the students said they preferred a coverage model course to one taught in a more focused manner.

To focus his teaching, Kelly decided to determine what the learning objectives for the course were and how he was going to assess whether or not the students had achieved the desired results. He followed Howard Gardner's advice, that a course should be designed with three concrete objectives in mind: "engage the central problem of the discipline, help students realize that source materials and subject matter do not exist in a pristine vacume, and give them opportunities to come at the same question or evidence from different perspectives."

Rather than approaching the curriculum as a chronology, (Plato to NATO in 14 weeks) Mills identified six essential concepts and broke the course into two-week blocks in which he addressed each of these main themes. Important events were discussed not in terms of what-happened-when, but in terms of how these happenings influenced larger concepts. The main objective was for students to gain skills and knowledge. Kelly's course design privileged understanding over information. He posted a detailed week-by-week chronicle of how the course unfolded.

Dr. Kelly's research led him to some interesting conclusions. He determined that students who access learning resources on the web display a higher level of recursive reading. According to Dr. Kelly, three-fourths of the students in the web sections went back to primary sources. Only one-fourth of students in the course section taught via print went back to materials assigned earlier in the semester. Their final essays bore out this finding, displaying a much lower use of sources assigned earlier in the semester.

Students I interviewed from the web sections said that because the documents they looked at from earlier in the semester were "just a click away," they were much more likely to use them. When I asked if they would have done the same thing with documents supplied in a course pack, all but one demurred, saying that, as one student put it, "having all that paper to sort through" would not be as immediate as a hyperlink. Or, as another student said in her interview, the web "is just easier to use than a book."

He found that the level of recursiveness was directly related to how well the web-based learning resources and assignments were designed.

He also concluded that the web does encourage independent investigation, but not as much as we would like, that the hypermedia revolution signals the doom of conventional history survey course, and historians must begin teaching web literacy. (He addresses this last conclusion in a more recent project, see below.)

Comments

The comment section addressed many interesting issues. I've decided to include excerpts from four authors on the two topics I felt were most important. First, there was a debate over Dr. Kelly's decision to focus on understanding rather than on facts.

Learning "facts" was not stated as a learning objective. One of the most widely touted examples of mediocrity in American public education is the dismal evidence that a significant proportion of people cannot correctly locate the Civil War within 50 years or so. Facts are important as a baseline for use of historical knowledge. -Samuel Thompson

This was refuted by Carolyn Schneider, who reminds us that reference books catalog the facts, but our job is to learn how the think and do.

ultimately, we don't want our students to KNOW as much as we want them to DO--which in our case would be THINKING, ANALYZING, EVALUATING--the "know" part they can always look up, and then that gets us to another "do"--which is research!

Another important point, had to do with the question of teaching vs. technology. Both commentors remind us that teaching is paramount, and solid course design always trumps technology.

I was struck by the extent to which student comments (Small Group Instructional Diagnosis) pertained not so much to web access as to the traditional classroom. Students remarked on the fact that you learned their names, that you delivered interesting lectures, that you encouraged discussions, that your grading focused too much on grammar, etc., etc. In other words, student consciousness of the web--whatever the reason--was certainly less over than my own. And perhaps that means--I should emphasize 'perhaps'--that the more conventional aspects of classroom teaching are still by far the most important thing in teaching, no matter whether the teacher hands them printed or web-accessible texts. -Dan Kaiser

This is especially noteworthy, to me, in your conclusions about technology and hypermedia--which do, as you say, have effects of various kinds but do not in themselves, alone, explain the most important things that do and do not happen in terms of student learning. What you show is that in a sense course design trumps technology. Or rather, technology needs to be seen as an aspect of course design rather than mostly as a different medium of delivery. This sounds obvious but I think it is not the dominant view. -Pat Hutchings

Dr. Kelly's Western Civilization Webography Project was a natural outgrowth of one of the conclusions he came to in his course portfolio research; historians must begin teaching web literacy.

Even the very best students simply do not think very much about whether or not a site is a good source of information. The only test most students impose on the sites they visit is a visual one--if the site appears to be very professional, then the information it contains must be valid.

The Webography project asks student to visit specific sites, rich with primary sources from European History. Students are given a rubric for analyzing the quality of the site. They review the site, assign it a numerical rating and write a brief review. These responses are posted to the database and made public. Dr. Kelly finds that this exercise significantly improves students' online research skills and, subsequently, the quality of their papers.

My on-going assessment of this project, dating back to the spring of 2003 is that very few of my students--meaning only one or two out of 50 in any given semester--turn in papers with poorly chosen websites once they have completed the webography project. In prior semesters as many as half of my students would receive reduced grades on writing assignments as a result of citing poor or misleading information from low quality sites.

In an email, Dr. Kelly told me of his latest efforts: "I have continued my research on the topics raised in my course portfolio, but have not put them into 'print.' Instead, I have funnelled my findings into various endeavors, such as World History Matters and the Western Civilization Webography Project. You'll see when you look at these, that I've veered from the more standard methods of representing my research into developing more practical applications of my findings for teachers and students."

Posted by kim white at 6:43 PM

September 21, 2005

Writing about Literature in the Media Age

Publishers are addressing the need for multiple media in the textbook marketplace by placing additional assets on CD-Rom and/or password-protected companion websites, and packaging them inside printed textbooks. This ubiquitous trio of resources reflects the inevitable (if glacial) move away from exclusive dependence on print media.

Daniel Anderson's "Writing about Literature in the Media Age," published by Pearson Longman, pushes the print/media genre forward a bit. Mr. Anderson's project weaves a network of connections that draw the separate elements together, and attempt to close the unavoidable gap between print and multimedia resources.

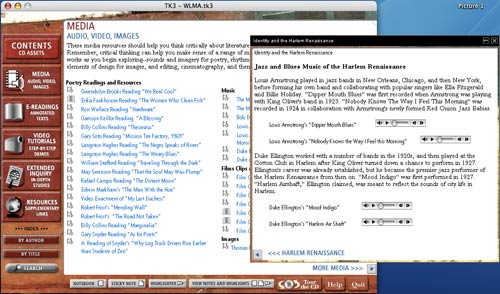

Most interesting of the media trio is the CD Rom, which provides students with extensive media assets for study and introduces strategies for close scrutiny of multimedia resources. The CD is divided into five sections: media, e-readings, video tutorials, extended inquiry, and resources.

The media section includes audio, video and images that correspond with readings in the print textbook. Below is a screen-grab of a page that offers audio samples of Harlem Renaissance poets and musicians. Asking a student to consider poetry and music side by side creates a unique opportunity for understanding how artists communicate across disciplines. It also allows them to survey the aural landscape of a literary work, and to consider how sound and rhythm are employed by skillful writers.

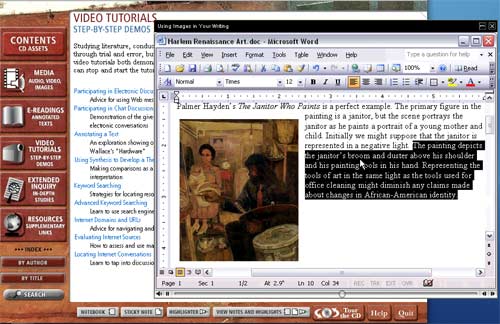

Most unique and useful are the video tutorials. Brief, but through mini-lessons on topics like: "Annotating a Text," "Giving Feedback Electronically," and "Using Images in Your Writing" (pictured below). The "Using Images" tutorial provides a clear example of how an image can enhance a written argument. It also gives the student instructions about how to place an image in a Word document, how to size the image and how to crop the image to focus the reader on a specific detail.

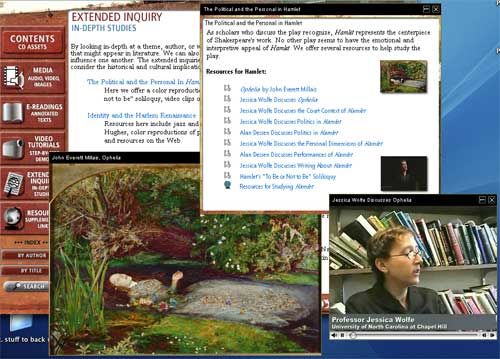

The "Extended Inquiry" section features five in-depth studies including, "The Political and the Personal In Hamlet." The print book has a corresponding section that includes the full text of Shakespeare's "Hamlet," along with a small sample of works created in response to the play. Among them, Margaret Atwood's short story, "Gertrude Talks Back"; Frederick Seidel's poem, "Hamlet"; and a black and white reproduction of John Everett Millais' "Ophelia." These responses to Hamlet introduce the lesson of artistic influence that the unit aims to teach. According to the book:

The works of Shakespeare have an incredible reach. Not only are quotations from his plays thrown around in our daily discourse, the larger messages of his works have become ingrained in the consciousness of contemporary society. Numerous artists have responded with paintings that represent scenes from Shakespeare's plays. Writers have composed adaptations and works that take up the key questions raised by the plays. Theatre companies have produced version of works like Hamlet continually for 400 years, and filmmakers regularly adapt Shakespeare's plays for the cinema.

The CD extends this argument with a color reproduction of John Everett Millais' "Ophelia," a reading of Hamlet's "to be or not to be" soliloquy, and video clips of scholars interpreting Hamlet. The Writing About Literature website extends the Hamlet inquiry even further with links to regularly updated online material.

Including these media items gives a graphic representation of the "incredible reach" that the work has. It shows the diversity and complexity of artistic influence and it draws the student closer to an understanding of what literary scholars do as they attempt to consider the work from all relevant angles. Additionally, the concept of "extended inquiry" (central to all scholarly work) is illuminated by the interweaving of book, CD, and web resources.

Posted by kim white at 11:25 AM

The Voyager Macbeth: An Expanded Critical Edition

Remember HyperCard? Apple's original, card-based graphical application made it possible to craft book-like works out of a database structure, allowing for multiple trajectories through the text and the intermingling of graphics and motion media. (Smackerel.net provides a nice refresher on "When Multimedia Was Black & White") Many of the works built in HyperCard have taken on the status of relics, but the best of them never fail to impress, reminding us that some of the biggest conceptual leaps in digital media were made over ten years ago, and in many ways remain unsurpassed.

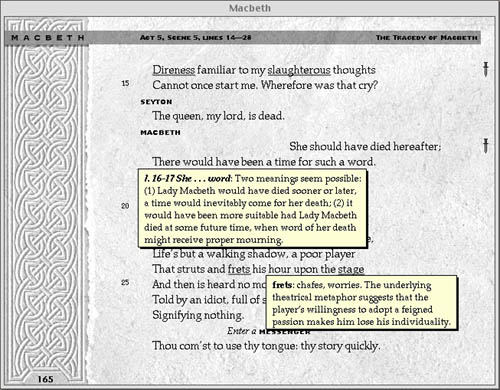

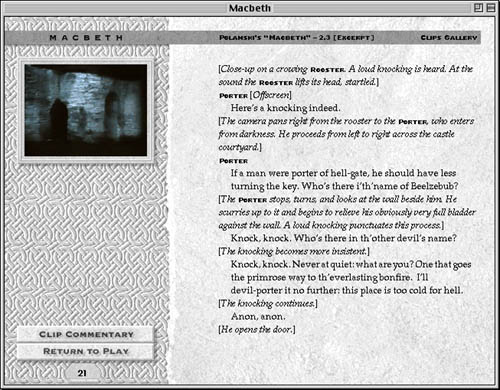

The Voyager Macbeth is a HyperCard-based CD-ROM that blew the lid off what seemed possible in a critical edition of a literary text (view demo). The disc is structured around the 1993 New Cambridge edition of the play, introduced by David Rodes, and thoroughly annotated by A.C. Braunmuller - both leading Shakespeare scholars and professors at UCLA. Producer and chief programmer Michael Cohen describes it as "a rich, immersive, book-like experience" - "a layered format." The text can be read, searched, listened to, watched, and even recited out loud with a pre-recorded actor reading opposite (a feature called "Macbeth Karaoke"). Trevor Nunn's seminal 1976 Royal Shakespeare Company production with Ian McKellan and Judy Dench supplies a complete audio track that can be brought into action instantly with a mouse click, beginning on any desired line. One can read the entire text this way, the pages turning automatically, with the impeccable cast of the RSC bringing it to life like a radio play.

Each page is rich with annotations, which can be summoned as pop-up windows by clicking on underlined words or passages. You can also click on little dagger icons in the margins that provide further context or tie a speech to other moments and motifs in the play, or little film strip icons that indicate video clips are available. Here opens another region of this vast edition. The editors have provided lengthy clips, with commentary, from three of the greatest screen adaptations of Shakespeare's tragedy - Orson Welles' Macbeth (1948), Akira Kurosawa's Throne of Blood (1957), and Roman Polanski's The Tragedy of Macbeth (1971) - all of which can be viewed (albeit on a small screen - this would be different now) within the book.

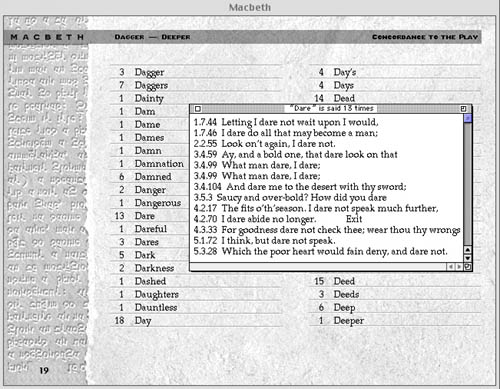

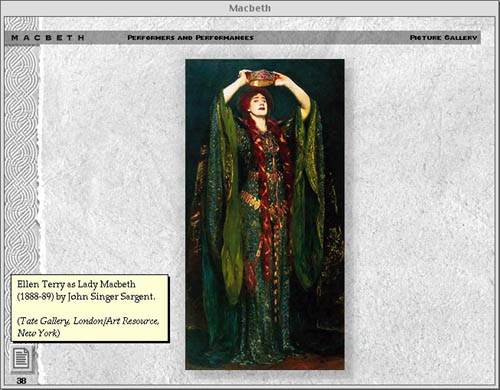

Other assets that expand the universe of the play and deepen the reader's investigation include a lengthy introduction by Professor Rodes, a library of critical essays, detailed background on Shakespeare's life and Elizabethan context, excerpts from the Holinshed Chronicles from which the play is drawn, a large archive of images documenting Macbeth's influence on western culture and various stage productions through the centuries, and important analytical tools such as character profiles, scene summaries and analysis, a full text concordance, and collation with other versions of the play (indispensable in Shakespeare scholarship). The only thing lacking, which could no doubt be solved if The Voyager Macbeth were being remade today, is the ability to write one's own notes in the text and to mark specific sections.

Chatting with Michael Cohen, I asked why so few electronic works of this caliber have been produced since the mid 90s. He pointed to the world wide web, which came into public use just as CD-ROMs were hitting their stride, and had the unfortunate effect of all but halting this period of development. "The web enables the making of small things." To some extent these things can be woven together, but the web is fundamentally not good at providing a center, which is essential for serious scholarship and textual analysis. "There is a place," he continued, "for well-considered, architected book-like materials." These materials should be able to weave together rich media and text in a way that paper cannot, yet still retain the focus and coherence of bounded print materials.

"But," I asked, "isn't the network something that should be used productively in these 'book-like' objects? There are resources on the web that can be of use, not to mention opportunities to communicate and work collaboratively with other students through the book. 'Macbeth Karaoke,' for instance, could incorporate a live chat tool that would make it possible to read with scene partners over the web." Or, students could interpret the text collaboratively with the Ivanhoe game (also profiled on nexttext). He agreed that the network should be fully employed, and that hopefully, tools would be developed that enabled the relatively easy production of bounded, media-rich works that can piggy-back on the web and draw on all the affordances of networked space. This suggests a vision of the future textbook that exists comfortably in the context of the web, and yet is not entirely of the web. Like a boat in the stream, it retains all the rigors and cohesion of the material world.

Cohen sees great potential in the recent increase in high school and university programs that provide laptops to every student. They'll need to load something on to that equipment, something more disciplined than a web browser. When you have unbroken access to your own machine, you can dive deeper - perhaps there is the potential for rich, immersive educational materials to make an entrance in programs like these.

Posted by ben vershbow at 8:17 AM

September 2, 2005

The NASA SCI Files: Problem-Based Learning Introduces Students to Scientific Inquiry

The NASA SCI Files is a research and standards-based series of free integrated mathematics, science, and technology instructional distance learning programs that NASA Langley Research Center created for students in grades 3-5. The series uses Problem-Based Learning (PBL) to introduce students to scientific inquiry while providing students the opportunity to solve real world problems with the help of community experts and NASA researchers.

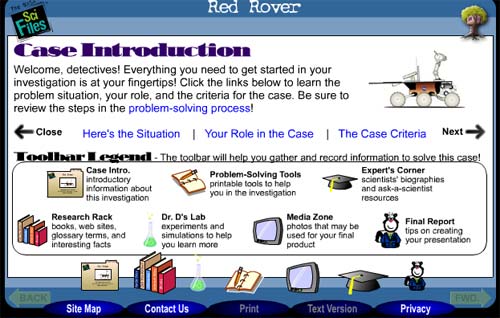

The program offers a series of television broadcasts that feature the tree house detectives, six children who solve "real world" problems using scientific inquiry. They are helped by their mentor Dr. D and also by NASA researchers, community experts, and students across the country who are members of the SCI Files Kids Club. The Website leads students through online investigations that can be used in tandem with the television broadcasts. Red Rover, for example, is used with "The Case of the Great Space Exploration." This problem-based activity asks students to research the requirements for crewed and uncrewed missions to Mars.

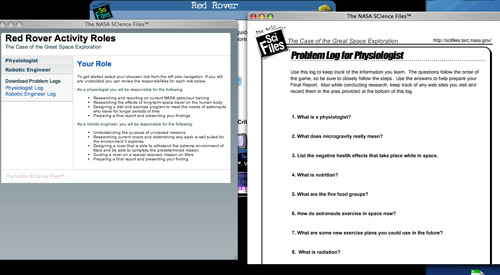

The students choose one of two roles, physiologist or robotics engineer. Each role has a list of research goals and project tasks. Once a role has been selected, the student prints out a "Program Log," with a list of ten questions such as: What is a Physiologist? What does microgravity really mean? How do astronauts exercise in space? Supplementary information, including text, diagrams, images and video, is available on the site to help students answer these challenging questions.

The nature of the supplementary information makes this resource different from a print textbook. Short videos explain long-term space travel problems such as: how food will be grown in space and how will the body be affected by zero gravity? These multi-media learning tools benefit visual and aural learners in ways that print textbooks cannot. Working through a tightly organized collection of media "clues", allows students to experience a sense of discovery while developing problem-solving skills. This dynamic would be difficult to duplicate in the static, linear-formatted print textbook. Finally, students are asked to write up a report of their findings. This journaling activity is designed to model the scientific process.

The NASA education site also provides extensive support for teachers. Educator guides (available as downloadable PDFs) list national science, math, or geography standards satisfied by each respective program. They also offer lesson-planning support including: a program overview, vocabulary, implementation strategy, activities, experiments and worksheets. Teachers can also sign up for classroom mentors, provided by the Society of Women Engineers. These mentors were specifically chosen to raise student awareness of careers in the sciences and to help students "overcome stereotyped beliefs by presenting women and minorities in challenging careers." The mentors assist educators either in person or by e-mail. Educators can find additional resources and support by contacting their local Educator Resource Center (ERC). "Personnel at ERCs located throughout the United States work with teachers to find out what they need and to share NASA's expertise. The ERCs provide educators with demonstrations of educational technologies such as NASA educational Web sites and NASA Television. ERCs provide inservice and preservice training utilizing NASA instructional products."

The depth and breadth of resources NASA has made available to students, parents, and educators makes the site more than just a digital textbook. It is a comprehensive subject-specific full-service digital learning environment. Created by top experts in the field, the space provides curriculum materials similar to those found in print textbooks, but it also vastly expands the territory of the print textbook and the process by which teachers and students explore subject matter.

Posted by kim white at 2:17 PM