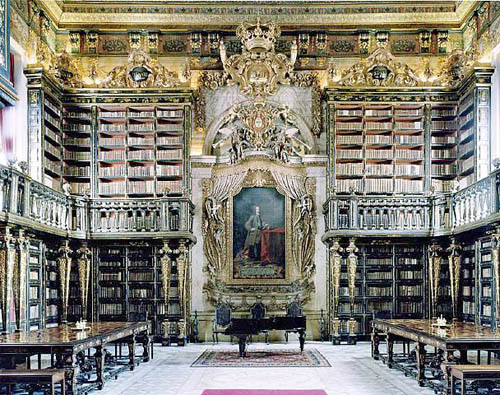

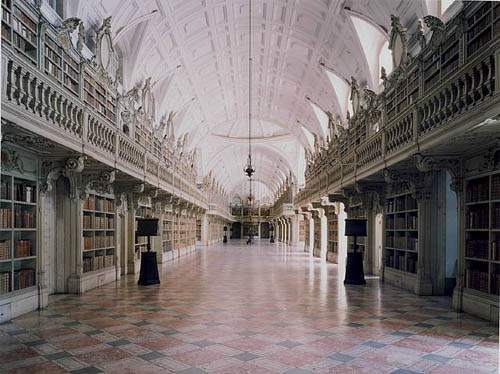

The photographs of libraries in “Portugal,” the current exhibition of Candida Höfer at Sonnabend, show libraries as venerable places where precious objects are stored.

The large format that characterizes Höfer’s photographs of public places, the absence of people, and the angle from which she composes them, invite the viewer “to enter” the rooms and observe. Photography is a silent medium and in Höfer’s libraries this is magnified, creating that feeling of “temple of learning” with which libraries have often been identified. On the other hand, the meticulous attention to detail, hand-painted porcelain markers, ornately carved bookcases, murals, stained glass windows, gilt moldings, and precious tomes are an eloquent representation of libraries as palaces of learning for the privileged. In spite of that, and ever since libraries became public spaces, anyone, in theory, has access to books and the concept of gain or monetary value rarely enters the user’s mind.

Libraries are a book lover’s paradise, a physical compilation of human knowledge in all its labyrinthine intricacy. With digitization, libraries gain storage capacity and readers gain accessibility, but they lose both silence and awe. Even though in the digital context, the basic concept of the library as a place for the preservation of memory remains, for many “enlightened” readers the realization that human memory and knowledge are handled by for-profit enterprises such as Google, produces a feeling of merchants in the temple, a sense that the public interest has fallen, one more time, into private hands.

As we well know, the truly interesting development in the shift from print to digital is the networked environment and its effects on reading and writing. If, as Umberto Eco says, books “are machines that provoke further thoughts” then the born-digital book is a step toward the open text, and the “library” that eventually will hold it, a bird of different feather.

Author Archives: sol gaitan

the encyclopedia of life

E. O. Wilson, one of the world’s most distinguished scientists, professor and honorary curator in entomology at Harvard, promoted his long-cherished idea of The Encyclopedia of Life, as he accepted the TED Prize 2007.

The reason behind his project is the catastrophic human threat to our biosphere. For Wilson, our knowledge of biodiversity is so abysmally incomplete that we are at risk of losing a great deal of it even before we discover it. In the US alone, of the 200,000 known species, only about 15% have been studied well enough to evaluate their status. In other words, we are “flying blindly into our environmental future.” If we don’t explore the biosphere properly, we won’t be able to understand it and competently manage it. In order to do this, we need to work together to help create the key tools that are needed to inspire preservation and biodiversity. This vast enterprise, equivalent of the human genome project, is possible today thanks to scientific and technological advances. The Encyclopedia of Life is conceived as a networked project to which thousands of scientists, and amateurs, form around the world can contribute. It is comprised of an indefinitely expandable page for each species, with the hope that all key information about life can be accessible to anyone anywhere in the world. According to Wilson’s dream, this aggregation, expansion, and communication of knowledge will address transcendent qualities in the human consciousness and will transform the science of biology in ways of obvious benefit to humans as it will inspire present, and future, biologists to continue the search for life, to understand it, and above all, to preserve it.

The first big step in that dream came true on May 9th when major scientific institutions, backed by a funding commitment led by the MacArthur Foundation, announced a global effort to launch the project. The Encyclopedia of Life is a collaborative scientific effort led by the Field Museum, Harvard University, Marine Biological Laboratory (Woods Hole), Missouri Botanical Garden, Smithsonian Institution, and Biodiversity Heritage Library, and also the American Museum of Natural History (New York), Natural History Museum (London), New York Botanical Garden, and Royal Botanic Garden (Kew). Ultimately, the Encyclopedia of Life will provide an online database for all 1.8 million species now known to live on Earth.

As we ponder about the meaning, and the ways, of the network; a collective place that fosters new kinds of creation and dialogue, a place that dehumanizes, a place of destruction or reconstruction of memory where time is not lost because is always available, we begin to wonder about the value of having all that information at our fingertips. Was it having to go to the library, searching the catalog, looking for the books, piling them on a table, and leafing through them in search of information that one copied by hand, or photocopied to read later, a more meaningful exercise? Because I wrote my dissertation at the library, though I then went home and painstakingly used a word processor to compose it, am not sure which process is better, or worse. For Socrates, as Dan cites him, we, people of the written word, are forgetful, ignorant, filled with the conceit of wisdom. However, we still process information. I still need to read a lot to retain a little. But that little, guides my future search. It seems that E.O. Wilson’s dream, in all its ambition but also its humility, is a desire to use the Internet’s capability of information sharing and accessibility to make us more human. Looking at the demonstration pages of The Encyclopedia of Life, took me to one of my early botanical interests: mushrooms, and to the species that most attracted me when I first “discovered” it, the deadly poisonous Amanita phalloides, related to Alice in Wonderland’s Fly agaric, Amanita muscaria, which I adopted as my pen name for a while. Those fabulous engravings that mesmerized me as a child, brought me understanding as a youth, and pleasure as a grown up, all came back to me this afternoon, thanks to a combination of factors that, somehow, the Internet catalyzed for me.

As we ponder about the meaning, and the ways, of the network; a collective place that fosters new kinds of creation and dialogue, a place that dehumanizes, a place of destruction or reconstruction of memory where time is not lost because is always available, we begin to wonder about the value of having all that information at our fingertips. Was it having to go to the library, searching the catalog, looking for the books, piling them on a table, and leafing through them in search of information that one copied by hand, or photocopied to read later, a more meaningful exercise? Because I wrote my dissertation at the library, though I then went home and painstakingly used a word processor to compose it, am not sure which process is better, or worse. For Socrates, as Dan cites him, we, people of the written word, are forgetful, ignorant, filled with the conceit of wisdom. However, we still process information. I still need to read a lot to retain a little. But that little, guides my future search. It seems that E.O. Wilson’s dream, in all its ambition but also its humility, is a desire to use the Internet’s capability of information sharing and accessibility to make us more human. Looking at the demonstration pages of The Encyclopedia of Life, took me to one of my early botanical interests: mushrooms, and to the species that most attracted me when I first “discovered” it, the deadly poisonous Amanita phalloides, related to Alice in Wonderland’s Fly agaric, Amanita muscaria, which I adopted as my pen name for a while. Those fabulous engravings that mesmerized me as a child, brought me understanding as a youth, and pleasure as a grown up, all came back to me this afternoon, thanks to a combination of factors that, somehow, the Internet catalyzed for me.

back to the backlist

An article in last Sunday’s NYT got me thinking about how book sales can be affected by media, in quite different ways than music, or even movies are, as illustrated in Chris Anderson’s blog mentioned here by Sebastian Mary. While bands, and even cineasts, are increasingly using the Web to share and/or distribute their productions for free, they are doing it in order to create a following; their future live audience in a theater or club. Something a bit different happens with classical music, and here I include contemporary groups that don’t fit the “band” label, where the concert experience usually precedes the purchase of the music. In the case of classical music, the public is usually people who can afford very high prices to see true luminaries at a great concert hall, and who probably don’t even know how to download music. The human aspect of the live show is what I find fascinating. A great soprano might be having a bad night and may just not hit that high note for which one paid that high price, but nothing beats the magic of sound produced by humans in front of one’s eyes and ears. Though I love listening to music alone, and the sounds of the digestion of the person sitting next to me in the theater mortify me, I wouldn’t exchange the experience of the live show for its perfectly digitized counterpart.

An article in last Sunday’s NYT got me thinking about how book sales can be affected by media, in quite different ways than music, or even movies are, as illustrated in Chris Anderson’s blog mentioned here by Sebastian Mary. While bands, and even cineasts, are increasingly using the Web to share and/or distribute their productions for free, they are doing it in order to create a following; their future live audience in a theater or club. Something a bit different happens with classical music, and here I include contemporary groups that don’t fit the “band” label, where the concert experience usually precedes the purchase of the music. In the case of classical music, the public is usually people who can afford very high prices to see true luminaries at a great concert hall, and who probably don’t even know how to download music. The human aspect of the live show is what I find fascinating. A great soprano might be having a bad night and may just not hit that high note for which one paid that high price, but nothing beats the magic of sound produced by humans in front of one’s eyes and ears. Though I love listening to music alone, and the sounds of the digestion of the person sitting next to me in the theater mortify me, I wouldn’t exchange the experience of the live show for its perfectly digitized counterpart.

This long preface to illustrate a similar, but rather odd, phenomenon. Russian Thinkers by Isaiah Berlin has disappeared from all bookshops in New York. Anne Cattaneo, the dramaturg of Tom Stoppard’s “The Coast of Utopia” (reviewed here by Jesse Wilbur) which opened at Lincoln Center on Nov. 27, provided in the show’s Playbill a list titled “For Audience Members Interested in Further Reading” with Russian Thinkers at the top. Since then, the demand for the book has been such, that Penguin has ordered two reprintings (3,500 copies) for the first time in the twelve years since the book has been printed, and which used to sell about 36 copies a month in the whole US. “A play hardly ever drives people to bookstores” says Paul Daly a book buyer, but Stoppard’s trilogy has moved its audience to resort not only to the learned notes inserted into the Playbill, but to further erudition on the Internet in order to figure out the more than 70 characters depicting Russia’s 19th century amalgam of intellectuals dreaming of revolution.

This long preface to illustrate a similar, but rather odd, phenomenon. Russian Thinkers by Isaiah Berlin has disappeared from all bookshops in New York. Anne Cattaneo, the dramaturg of Tom Stoppard’s “The Coast of Utopia” (reviewed here by Jesse Wilbur) which opened at Lincoln Center on Nov. 27, provided in the show’s Playbill a list titled “For Audience Members Interested in Further Reading” with Russian Thinkers at the top. Since then, the demand for the book has been such, that Penguin has ordered two reprintings (3,500 copies) for the first time in the twelve years since the book has been printed, and which used to sell about 36 copies a month in the whole US. “A play hardly ever drives people to bookstores” says Paul Daly a book buyer, but Stoppard’s trilogy has moved its audience to resort not only to the learned notes inserted into the Playbill, but to further erudition on the Internet in order to figure out the more than 70 characters depicting Russia’s 19th century amalgam of intellectuals dreaming of revolution.

Penguin has asked Henry Hardy, one of the original editors of the book to prepare a new edition that could be reissued as a Penguin Classic. If all this is product of a play whose audience is evidently interested in extracting, and debating, the meaning of its characters, a networked edition would have made great sense. Printed matter seems to have proven insufficient here.

future of the filter

An article by Jon Pareles in the Times (December 10th, 2006) brings to mind some points that have been risen here throughout the year. One, is the “corporatization” of user-generated content, the other is what to do with all the material resulting from the constant production/dialogue that is taking place on the Internet.

Pareles summarizes the acquisition of MySpace by Rupert’s Murdoch’s News Corporation and YouTube by Google with remarkable clarity:

What these two highly strategic companies spent more than $2 billion on is a couple of empty vessels: brand-named, centralized repositories for whatever their members decide to contribute.

As he puts it, this year will be remembered as the year in which old-line media, online media and millions of individual web users agreed. I wouldn’t use the term “agreed,” but they definitely came together as the media giants saw the financial possibilities of individual self-expression generated in the Web. As it usually happens with independent creative products, large amounts of the art originated in websites such as MySpace and YouTube, borrow freely and get distributed and promoted outside of the traditional for-profit mechanisms. As Pareles says, “it’s word of mouth that can reach the entire world.” Nonetheless, the new acquisitions will bring a profit for some while the rest will supply material for free. But, problems arise when part of that production uses copyrighted material. While we have artists fighting immorally to extend copyright laws, we have Google paying copyright holders for material used in YouTube, but also fighting them.

The Internet has allowed for the democratization of creation and distribution, it has made the anonymous public while providing virtual meeting places for all groups of people. The flattening of the wax cylinder into a portable, engraved surface that produced sound when played with a needle, brought the music hall, the clubs and cabarets into the home, but it also gave rise to the entertainment business. Now the CD burner, the MP3, and online tools have brought the recording studio into the home. Interestingly enough, far from promoting isolation, the Internet has generated dialogue. YouTube is not a place for merely watching dubious videos; it is also a repository of individual reactions. Something similar is happening with film, photography and books. But, what to do with all that? Pareles sees the proliferation of blogs and the user-generated play lists as a sort of filter from which the media moguls are profiting: “Selection, a time-consuming job, has been outsourced. What’s growing is the plentitude not just of user-generated content, but also of user-filtered content.” But he adds, “Mouse-clicking individuals can be as tasteless, in the aggregate, as entertainment professionals.” What is going to happen as private companies become the holders of those filters?

on today’s publications

On November 27 the Pulitzer Prize Board announced that “newspapers may now submit a full array of online material-such as databases, interactive graphics, and streaming video-in nearly all of its journalism categories,” while the closest The New York Times’ 100 Notable Books of the Year came to documenting any changes in the publishing world is one graphic memoir (Fun Home by Alison Bechdel.)

On November 27 the Pulitzer Prize Board announced that “newspapers may now submit a full array of online material-such as databases, interactive graphics, and streaming video-in nearly all of its journalism categories,” while the closest The New York Times’ 100 Notable Books of the Year came to documenting any changes in the publishing world is one graphic memoir (Fun Home by Alison Bechdel.)

Only last year the Pulitzer Prize Board allowed for the first time some online content, but now, it will permit a broader, and much more current assortment of online elements, according to the different Pulitzer categories. The seemingly obvious restrictions are for photography, which permit still images only. They have decided to catch up with the times: “This board believes that its much fuller embrace of online journalism reflects the direction of newspapers in a rapidly changing media world,” said Sig Gissler, administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes. With its new rules for online submissions, the Pulitzer Board acknowledges that online elements such as a database, blog, interactive graphic, slide show, or video presentation count as items in the total number of elements, print or online, that can be considered worth a prize.

Even though the use of multimedia and computer technology has become ubiquitous not only in the media world but also in the performing arts, the book world seems absorbed in its own universe. The notion of “digital book” continues to mean digital copies of books and the consequent battle among those who want the lion’s share of the market (see “Yahoo Rebuffs Google on Digital Books”). And, when we talk about ebooks we mean devices for reading digital copies of books. Interestingly, most of the books published today are written, composed and set using electronic technology. So much of what we read online is full of distracting, sometimes quite interesting, advertising. On Black Friday, lots of people following the American tradition of shopping on that day did it online. It would seem that we are more than ready for real ebooks. I wonder how long it would take for one of them to hit the top lists of the year.

new love meetings: “il primo film girato con un telefonino”

Leafing through my hardcopy of the September/October edition of Filmcomment, published by the Film Society of Lincoln Center, I came across a mini-review of “New Love Meetings,” co-directed by Marcello Mencarini and Barbara Seghezzi. First featured in The Guardian Unlimited, this story was newsworthy because this film is reportedly the first feature (93 minutes) entirely shot with a cell phone. “New Love Meetings” was filmed in MPEG4 format using a Nokia N90, and follows on Pasolini’s 1965 documentary “Love Meetings,” in which he interviewed Italian men and women about their views on sex in postwar Italy. Mencarini and Seghezzi used cell phones to interview about 700 people at regular meeting places such as bars, markets, the beach, etc.

Leafing through my hardcopy of the September/October edition of Filmcomment, published by the Film Society of Lincoln Center, I came across a mini-review of “New Love Meetings,” co-directed by Marcello Mencarini and Barbara Seghezzi. First featured in The Guardian Unlimited, this story was newsworthy because this film is reportedly the first feature (93 minutes) entirely shot with a cell phone. “New Love Meetings” was filmed in MPEG4 format using a Nokia N90, and follows on Pasolini’s 1965 documentary “Love Meetings,” in which he interviewed Italian men and women about their views on sex in postwar Italy. Mencarini and Seghezzi used cell phones to interview about 700 people at regular meeting places such as bars, markets, the beach, etc.

Cell-phone short movies have become ubiquitous in the Internet, and they have achieved some visibility in film festivals, but Mencarini and Seghezzi’s premise is that even though they asked very much the same questions that Pasolini posed, the results of their film are marked by the medium they used to shoot it. The use of a cell phone, an instrument that belongs to people’s daily lives, produced an intimacy absent in Pasolini’s movie. In a way, the filmmakers were very much like normal people using their cell phones to preserve an instant. This leads people to be more spontaneous and open, making the dialogue more like a chat than an interview.

This technique underscores the fact that today, memories can be captured and disseminated instantly thanks to the nature of our networked world, and that the way we preserve them is not the realm of books, not even of traditional films. Memory is instant, intimacy is public, and we communicate more readily than ever before. People have used stone, scrolls, print, wax cylinders, film, and tape, to preserve and disseminate memories, “New Love Meetings” is yet another example of the permeability and plasticity of mediums within which we move today. We cannot apply traditional, orthodox aesthetic values to the hybrid products of the moment. Experimentation doesn’t follow a master plan.

carbon and silver

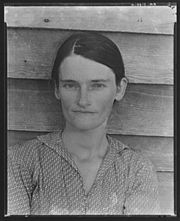

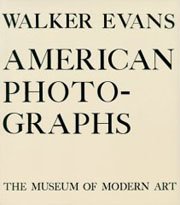

Carbon and Silver is a small show of Walker Evans‘ 1935-36 photographs at the UBS gallery in New York. The purpose of this exhibit is to compare printing technologies. It focuses primarily on ink-jet prints in relation to gelatin silver prints, with a small sample of books side by side with their digitally printed counterparts, revealing how lithography literally pales next to the crispness of the digital.

Carbon and Silver is a small show of Walker Evans‘ 1935-36 photographs at the UBS gallery in New York. The purpose of this exhibit is to compare printing technologies. It focuses primarily on ink-jet prints in relation to gelatin silver prints, with a small sample of books side by side with their digitally printed counterparts, revealing how lithography literally pales next to the crispness of the digital.

The show invites meditations on the “authenticity” of reproductions, especially in a medium such as photography, in itself based upon printing technology. In this show it is quite difficult to discern the original from the copy, and one questions, as Baudrillard would have it, to which point the copy has come to replace the original.

Most of the prints exhibited at the UBS belong to Evans’ body of work documenting the effect of the Great Depression on rural families for the Farm Security Administration in 1935-36. As a photographer, he was not particularly interested in producing his own prints as his main interest was to record information. These photographs were originally printed by the FSA as visual evidence reinforcing the New Deal.

Most of the prints exhibited at the UBS belong to Evans’ body of work documenting the effect of the Great Depression on rural families for the Farm Security Administration in 1935-36. As a photographer, he was not particularly interested in producing his own prints as his main interest was to record information. These photographs were originally printed by the FSA as visual evidence reinforcing the New Deal.

Evans’ own interpretation of them appeared in American Photographs, the book that accompanied his exhibition at the Museum of Modern art (the first one-man photography show ever mounted by a major museum.) John T. Hill says in this exhibition’s catalogue that Evans “scrupulously controlled corrections of the printing plates, and using this process as an extension of his darkroom became a habit.” The interesting thing is that he understood that the book has a permanence that the exhibition does not.

Evans’ photographs have such crispness that they lend themselves to reproduction, even when the print is less than perfect. As a master of his medium he was absolutely aware of the difficulties of rendering full tonal scale in a black and white print. The ink-jet prints in this show are so remarkably close to their gelatin silver sisters that the viewer has to go back and forth from print to print in order to discern any possible difference. Evans loved the detail that an enlarged print brings out and the enlarged digital prints in this exhibition certainly do that.

Hill sums up the advantages of technology without denigrating the magnificence of the original process:

All new media affect voice and timbre. A greater tonal scale and more precise control of values are the two most significant tools offered by digital technology. The information so difficult to maintain in the dark and light ends of the scale using gelatin silver materials is now printable. Gelatin silver has been replaced by carbon black pigments laid onto archival paper. The music is the same; certain subtle notes are now heard more clearly.

art as politics

The term “political art” has implications that might well deter people from viewing it, especially here where the political is regarded as unaesthetic. It is sad that when an American artist makes “political art” it becomes news. This has been the case with the presence of political films in Cannes, as chronicled by A. O. Scott in the New York Times. He makes a parallel with the 60’s as a golden age of filmmaking, and in particular the 1968 Cannes Film Festival, where the artistic and the political were absolutely interconnected. To say that the problems we are facing today are less significant than those of the 60’s is to exchange lack of hope for the authentic belief in change that permeated that era.

The big difference today is that communications are immediate and indispensable, but that their ubiquity has also numbed us. War and catastrophe as spectacle have always fed the public imagination, but today fiction and fact, reality and artifice, have collapsed into yet another consumer product. On the other hand, the availability of affordable technology has made photography, video and filmmaking accessible to many. Now, it is possible to see interesting and good quality pieces from places far away from the established centers of film production. Cannes is still the favorite showplace of international cinema, but it doesn’t mean that many movies that make it there ever go beyond the art houses. So, the presence of Al Gore’s “An Inconvenient Truth,” Richard Linklater and Eric Schlosser’s “Fast Food Nation” or Linklater’s “A Scanner Darkly” and Richard Kelly’s “Southland Tales” are news not because they are represented in Cannes but because they tell stories based on present circumstances without fear of being “political.”

Holland Cotter the art critic of The New York Times reviews some current exhibitions that make political commentary noting that in 21st-century America political art is not “protest art” but a mirror. But, what else is art, past and present, than a mirror that uncannily shows political realities? The fact that many artists insist on looking at their belly buttons instead of at the world, is in itself a political commentary of the times. Cotter reviews Harrell Fletcher’s http://www.harrellfletcher.com/# show at White Columns, images from a museum in Ho Chi Minh City, as a horrific document of the Vietnam War. Jenny Holzer at Cheim and Read shows a series of silk screens of declassified documents related to Abu Ghraib, which are faithful to each official word with the exception of their magnification, thus becoming a commentary on our nation’s violence.

from Archive — Jenny Holzer

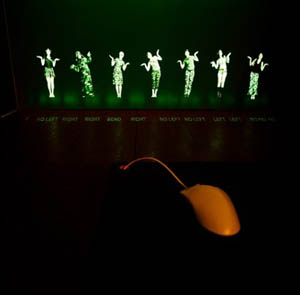

Coco Fusco‘s video, “Operation Atropos,” documenting the training on interrogation and resistance program she and six women went through in the woods of the Poconos, offers a political glance at the methods of physical and mental persuasion. Apart from the obviously political, the viewer realizes that this program, run by former members of the CIA, has been conceived for the private sector.

Operation Atropos

Cotter concludes his article asking, “So what kind of political art is this? It isn’t moralizing or accusatory. It’s art for a time when play-acting and politics seem to be all but indistinguishable.” They are.

It is always enormously refreshing to visit the art galleries, and to be reminded that many artists in many places, perhaps because they are faced with stark realities on a daily basis, have indeed a lot to comment. The Asian Contemporary Art Week (5/22-5/27) was one of those occasions (and still is since many galleries will continue displaying Asian art for a few more weeks.) Shilpa Gupta‘s interactive video environments at Bose Pacia offer a comment on power, militarism and imperialism. In one of the pieces the viewer sees a bucolic landscape in Kashmir and as s/he touches the screen military guards appear. Truth is indeed a fragile and many times deceiving construction.

Untitled, 2005 — Shilpa Gupta

Tejal Shah‘s video installation at Thomas Erben presents the transgender community in India from within, a reality that is equally painful and celebratory. At the Sculpture Center, as part of the Grey Flags exhibition, there is a film by Apichatpong Weerasethakul the Thai filmmaker whose fresh approach to reality has taken him to use non-professional actors and improvised dialogue, offering a sober and supetcharged vision of reality in Thailand. Tilton Gallery brings together 34 contemporary Chinese artists entitled “Jiang Hu” whose literal meaning is “rivers and lakes” but that metaphorically means a place removed from the mainstream. In medieval literature it means a realm inhabited by outsiders, monks, fortune-tellers and artists who had magical powers. In the context of this exhibit that shows an interesting and disparate group, “Jiang Hu” evokes a complex reality: China an outsider within the global world.

on appropriation

The Tate Triennial 2006, showcasing new British Art, brings together thirty-six artists who explore the reuse and reshaping of cultural material. Curated by Beatrix Ruf, director of the Kunsthalle in Zurich, the exhibition includes artists from different generations who explore reprocessing and repetition through painting, drawing, sculpture, photography, film, installations and live work.

Historically, the appropriation of images and other cultural matter has been practiced by societies as the reiteration, reshuffling, and eventual transformation of artistic and intellectual human manifestations. It covers a vast range from tribute to pastiche. When visual codes are combined, the end product is either a cohesive whole where influences connect into new and very personal languages, or disparate combinations where influences compete and clash. In today’s art, the different guises of repetition, from collage and montage to file sharing and digital reproduction highlight the existing codes or reveal the artificiality of the object. Today’s combination of codes alludes to a collective sense of memory in a moment when memories have become literally photographic.

One comes out of this exhibition thinking about Duchamp‘s “readymades,” Rauschenberg’s “combines,” and other forms of conceptual “gluing,” (the literal meaning of the word “collage,”) as precursors and/or manifestations of the postmodern condition. This show is a perfect representation of our moment. As Beatrix Ruf says in the catalogue: “Artists today are forging new ways of making sense of reality, reworking ideas of authenticity, directness and social relevance, looking again into art practices that emerged in the previous century.”

We have artists like Michael Fullerton, who paints contemporary figures in the style of Gainsborough, or Luke Fowler‘s use of archive material to explore the history of Cornelius Cardew’s Scratch Orchestra. Repetition goes beyond inter-referentiality in the work of Marc Camille Chaimowicz, who combines works he made in the 70s with projected images of himself as a young man and as an adult, within a space where a vase of flowers set on a Marcel Breuer’ table and a pendulum swinging back and forth position the images of the past solidly in the present. In “Twelve Angry Women,” Jonathan Monk affixes to the wall twelve found drawings by an unknown artist from the 20s, using different colored pins that work as earrings. Mark Leckey uses Jeff Koons’ silver bunny as a mirror into his studio in the way 17th century masters painted theirs. Liam Gillick creates sculptures of hanging texts made out of factory signage.

Art itself is cumulative. Different generations build upon previous ones in a game of action and reaction. One interesting development in art today is the collective. Groups of artists coming together in couples, teams, or cyberspace communities, sometimes under the identity of a single person, sometimes a single person assuming a multiple identity. Collectives seem to be a new phenomenon, but their roots go back to the concept of workshops in antiquity where artistic collaboration and copying from casts of sculptural masterpieces was the norm. The notion of the individual artist producing radically new and original art belongs to modernity. The return to collectives in the second part of the 20th century, and again now, has a lot to do with the nature of representation, with the desire to go beyond the limits of artistic mimesis or individual interpretation.

On the other hand, appropriation as a form of artistic expression is a postmodern phenomenon. Appropriation is the language of today. Never before the advent of the Internet had people appropriated knowledge, spaces, concepts, and images as we do today. To cite, to copy, to remix, to modify are part of our everyday communication. The difference between appropriation in the 70s and 80s and today resides in the historical moment. As Jean Verwoert says in the Triennial 2006 catalogue:

The standstill of history at the height of the Cold War had, in a sense, collapsed the temporal axis and narrowed the historical horizon to the timeless presence of material culture, a presence that was exacerbated by the imminent prospect that the bomb could wipe everything out at any time. To appropriate the fetishes of material culture, then, is like looting empty shops at the eve of destruction. It is the final party before doomsday. Today, on the contrary, the temporal axis has sprung up again, but this time a whole series of temporal axes cross global space at irregular intervals. Historical time is again of the essence, but this historical time is not the linear or unified timeline of steady progress imagined by modernity: it is a multitude of competing and overlapping temporalities born from the local conflicts that the unresolved predicaments of the modern regimes still produce.

Today, the challenge is to rethink the meaning of appropriation in a moment when capitalist commodity culture has become the determinant of our daily lives. The Internet is perhaps our potential Utopia (though “dystopian” seems to be the adjective of choice now.) But, can it be called upon to fulfill the unfulfilled promises of 20th century’s utopias? To appropriate is to resist the notion of ownership, to appropriate the products of today’s culture is to expose the unresolved questions of a world shaped by the information era. The disparities between those who are entering the technology era and those forced to stay in the times of early industrialization are more pronounced than ever. As opposed to the Cold War, where history was at a standstill, we live in a time of extreme historicity. Permanence is constantly challenged, how to grasp it all continues to be the elusive task.

truth through the layers

Pedro Meyer’s I Photograph to Remember is a work originally designed for CD ROM, that became available on the Internet 10 years later. I find it not only beautiful within the medium limitations, as Pedro says on his 2001 comment, but actually perfectly suited for both, the original CD ROM, and its current home on the internet . It is a work of love, and as such it has a purity that transcends all media.

Pedro Meyer’s I Photograph to Remember is a work originally designed for CD ROM, that became available on the Internet 10 years later. I find it not only beautiful within the medium limitations, as Pedro says on his 2001 comment, but actually perfectly suited for both, the original CD ROM, and its current home on the internet . It is a work of love, and as such it has a purity that transcends all media.

The photographs and their subject(s) have such degree of intimacy that forces the viewer to look inside and avoid all morbidity or voyeurism. The images are accompanied by Pedro Meyer’s voice. His narration, plain and to the point, is as photographic as the pictures are eloquent. The line between text and image is blurred in the most perfect b&w sense. The work evokes feelings of unconditional love, of hands held at moments of both weakness and strength, of happiness and sadness, of true friendship, which is the basis of true love. The whole experience becomes introspection, on the screen and in the mind of the viewer.

IPTR was originally a Voyager CD ROM, and it was the first ever produced with continuous sound and images, a possibility that completes, and complements, image as narration and vice-versa. The other day Bob Stein showed me IPTR on his iPod and expressed how perfectly it works on this handheld device. And, it does. IPTR is still a perfect object, and as those old photographs exist thanks to the magic of chemicals and light, this exists thanks to that “old” CD ROM technology, and will continue to exist inhabiting whatever medium necessary to preserve it.

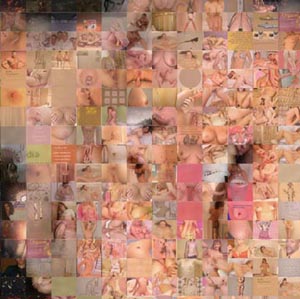

I’ve recently viewed Joan de Fontcuberta’s shows in two galleries in Manhattan; Zabriskie and Aperture,) and the connections between IPTR and these works became obsessive to me. Fontcuberta, also a photographer, has chosen the Internet, and computer technology, as the media for both projects. In “Googlegrams,” he uses the Google image search engine to randomly select images from the Internet by controlling the search engine criteria with only the input of specific key words.

I’ve recently viewed Joan de Fontcuberta’s shows in two galleries in Manhattan; Zabriskie and Aperture,) and the connections between IPTR and these works became obsessive to me. Fontcuberta, also a photographer, has chosen the Internet, and computer technology, as the media for both projects. In “Googlegrams,” he uses the Google image search engine to randomly select images from the Internet by controlling the search engine criteria with only the input of specific key words.

These Google-selected images are then electronically assembled into a larger image, usually a photo, of Fontcuberta’s choosing (for example, the image of a homeless man sleeping on the sidewalk reassembled from images of the 24 richest people in the world, Lynddie England reassembled from images of the Abu Ghraib’s abuse, or a porno picture reassembled from porno sites.). The end result is an interesting metaphor for the Internet and the relationship between electronic mass media and the creation of our collective consciousness.

For Fontcuberta, the Internet is “the supreme expression of a culture which takes it for granted that recording, classifying, interpreting, archiving and narrating in images is something inherent in a whole range of human actions, from the most private and personal to the most overt and public.” All is mediated by the myriad representations on the global information space. As Zabriskie’s Press Release says, “the thousands of images that comprise the Googlegrams, in their diminutive role as tiles in a mosaic, become a visual representation of the anonymous discourse of the internet.”

Aperture is showing Fontcuberta’s “Landscapes Without Memory” where the artist uses computer software that renders three-dimensional images of landscapes based on information scanned from two-dimensional sources (usually satellite surveys or cartographic data.) In “Landscapes of Landscapes” Fontcuberta feeds the software fragments of pictures by Turner, Cézanne, Dalí, Stieglitz, and others, forcing the program to interpret this landscapes as “real.”

Aperture is showing Fontcuberta’s “Landscapes Without Memory” where the artist uses computer software that renders three-dimensional images of landscapes based on information scanned from two-dimensional sources (usually satellite surveys or cartographic data.) In “Landscapes of Landscapes” Fontcuberta feeds the software fragments of pictures by Turner, Cézanne, Dalí, Stieglitz, and others, forcing the program to interpret this landscapes as “real.”

These painted and photographic landscapes are transformed into three-dimensional mountains, rivers, valleys, and clouds. The result is new, completely artificial realities produced by the software’s interpretation of realities that have been already interpreted by the painters. In the “Bodyscapes” series, Fontcuberta uses the same software to reinterpret photographs of fragments of his own body, resulting in virtual landscapes of a new world. By fooling the computer Fontcuberta challenges the limits between art, science and illusion.

Both Pedro Meyer and Joan de Fontcuberta’s use of photography, technology and the Internet, present us with mediated worlds that move us to rethink the vocabulary of art and representation which are constantly enriched by the means by which they are delivered.