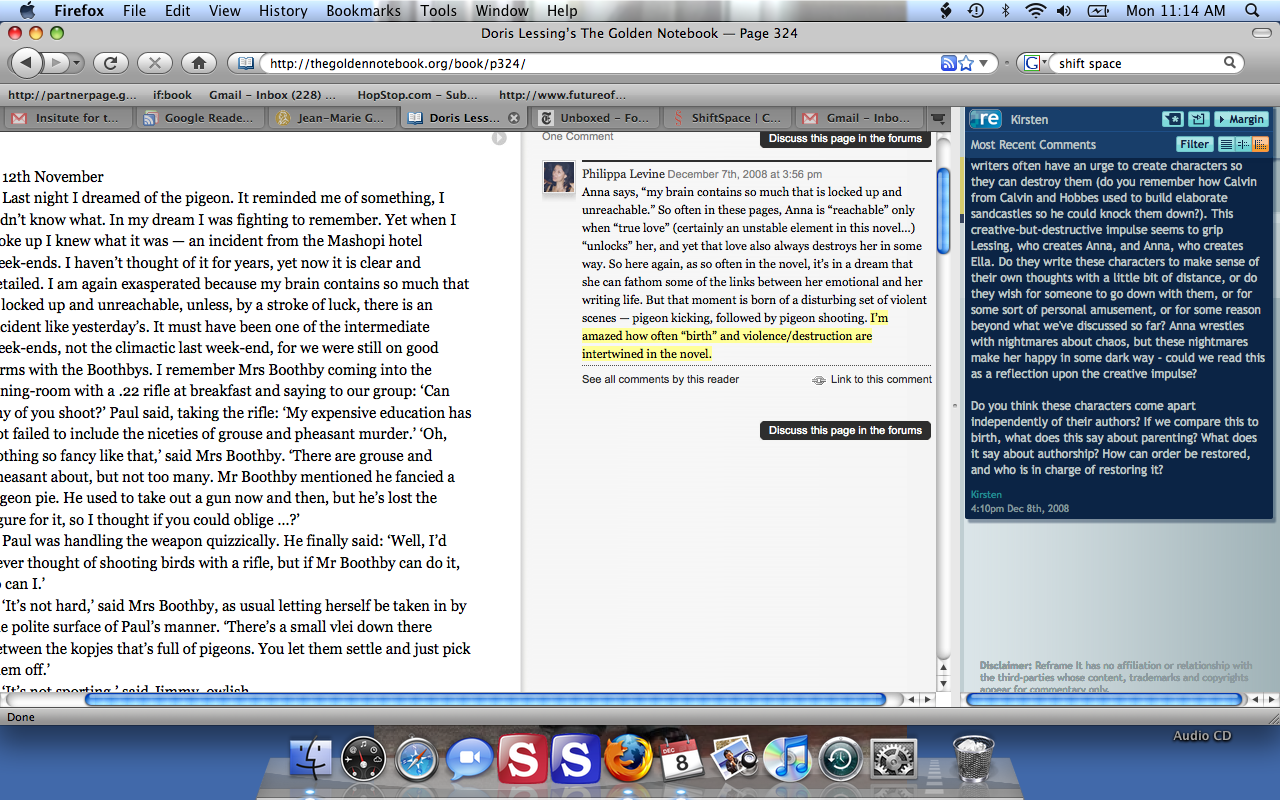

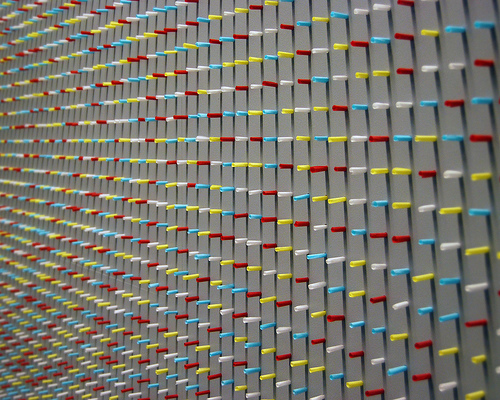

A screen is an extremely limited amount of space. We knew when we started The Golden Notebook Project that we could only fit about seven readers comfortably within the margins of the book. However, we are not interested solely in these seven (wonderful) readers; we want the public to contribute to the discussion. A program called ReframeIt allows you to annotate any page on the web, and we’d like to try it for the Project. ReframeIt displays tiny colored boxes in the sidebar that expand into full comments – this isn’t especially pretty, but it allows for many more comments in a single sidebar than you would have if you displayed every comment in its entirety, making room for many more comments than before. The program also allows you to highlight (as shown above) and allows for all sorts of social networking. We’re excited to try this for The Golden Notebook so that the original text, the seven readers’ comments, and public comments can be in one space (rather than dividing the readers’ comments and the public forums into separate pages). We would like to invite you to join and follow along in the margins with us. You can download the Firefox extension here.

Author Archives: kirsten reach

Variations on a theme

I spent a day last week at MASS MoCA, touring Sol LeWitt: A Wall Drawing Retrospective. (It was finally profiled in the New York Times this morning, and NPR reported it yesterday.) The exhibit takes up an entire building, wall after wall installed for the (re)creation of LeWitt’s work. LeWitt did not want his work to be limited to a single canvas; he created careful records of each of his drawings so they could be produced on any wall by himself or other artists. He compared this to architecture and music; it can be reproduced and will vary depending upon the people and spaces involved in each production. He planned this exhibit well before his death last year.

For the retrospective, MASS MoCA commissioned sixty-odd students and artists, among them Adrian Piper and Jerry Orter, to produce the wall drawings. Thousands of crayons, graphite pencils, colored pencils, and gallons of acrylic paint later, Building 7 was transformed into a celebration of LeWitt’s career.

Walking through the building is like walking through LeWitt’s brain: you can see his earliest experiments and echoes of these in his later work. These pieces are presented in a way that is varied and spectacular in the exhibit; I am going to present them below in a much more linear format, but you have to go visit to get the full effect. (Unless otherwise noted, all photos in this entry belong to MASS MoCA.)

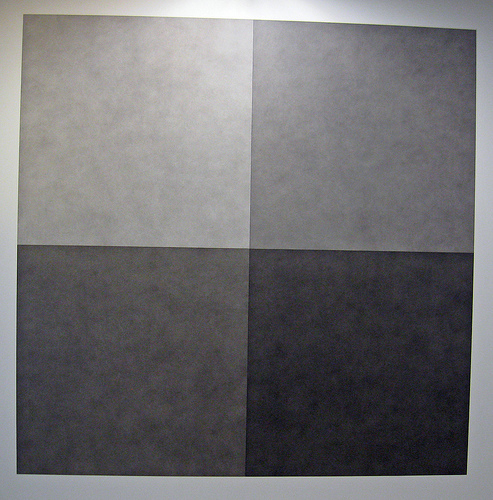

He begins with simple lines, and advances to levels of shading.

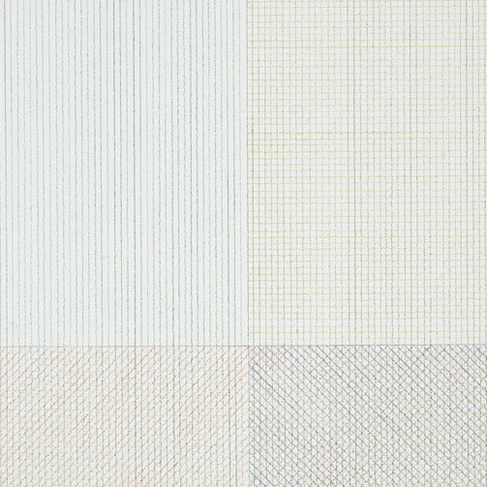

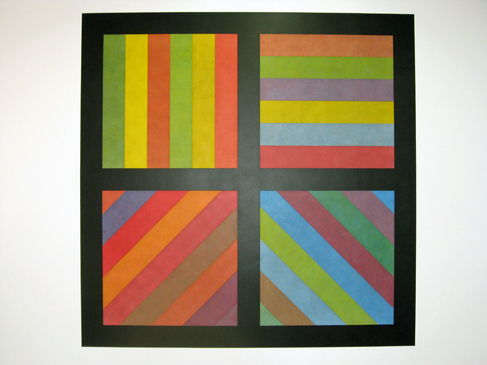

You can see his first foray into the world of color, then what seems to be his signature (four blocks) emerge from these. LeWitt doesn’t blend colors, he layers one color on top of another. He often uses diagonal lines coming from several directions in primary colors, in the following pattern: vertical, horizontal, diagonal left, and diagonal right. He superimposes these lines to create gradations in colors (or greys).

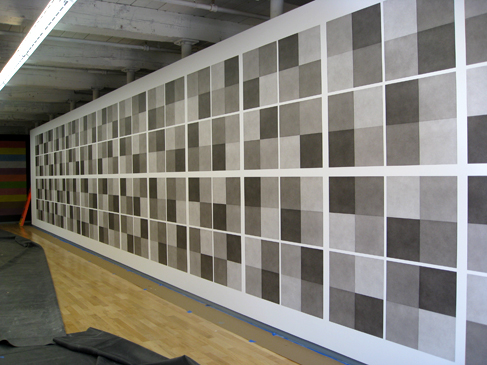

He places the blocks together like a quilt pattern that can span an enormous amount of space.

He (or rather, his talented production team) then blends color by carefully layering primary colors directly on the wall. The result is something like this:

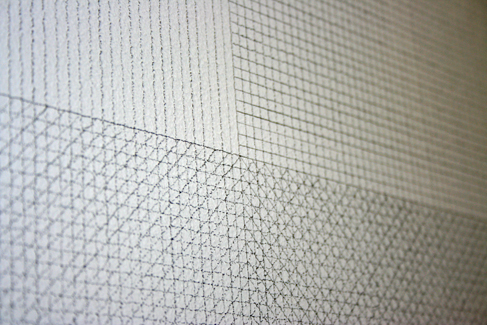

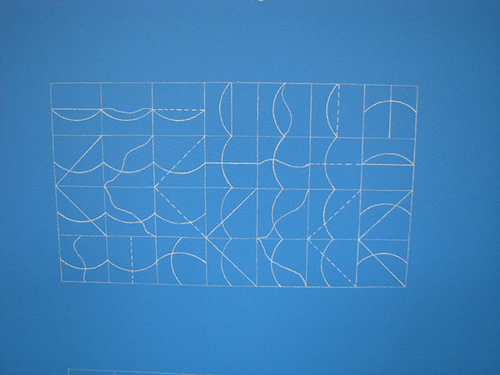

If you look carefully, you see the grids beneath his work. One piece, produced originally on white walls with blue lines, and produced in this retrospective on blue walls with white lines, is a clear demonstration of his lexicon. LeWitt uses music terms to explain how his work is produced. I must resort to linguistic terms to describe it – even the brochure slips into a description of his shapes as though they are language. This blue piece is the largest in the exhibit, showing each of the forms LeWitt used at the time, and presenting them all together on a grid. The grid is still visible in the finished product, and piece feels like a blueprint as well as a finished product. LeWitt worked with an architect for a time, and it’s hard not to compare his work to architecture, geometry, or even early computer programming (which was going on as some of his work was being created).

I’m including the second photo with people in it so you can imagine how your relationship with this piece will change when you see in on four walls that tower above you. A piece like this completely immerses the museum-goer the language of his compositions. As you explore, you can learn the syntax of each color, each painting technique, and each pattern. Once you understand the rules, the artist can break them. On the third floor, LeWitt throws walls at you like this:

That’s Wall Drawing 958, with the description “Splat.” LeWitt subverts his own vocabulary. He leaves behind the “Splat” plan on a sheet for an overhead projector – perhaps he grew less interested in the variation borne of multiple production teams and many different spaces. (If he had been a composer, this would be the point in his life where he records himself playing all the parts of a piece instead of leaving it up to interpretation.)

One of his later pieces that I especially like is below. Everyone who walked by seemed to comment upon its resemblance to a board game. The instructions LeWitt wrote say specifically that none of the same colors can touch, and no matter how carefully the draftsmen planned, they inevitably had to touch it up to make sure this order was preserved.

Sol Lewitt Wall Drawing #1112 & #1152 from jackadam on Vimeo.

His final pieces seem to wait quietly to the side while his brightest walls parade around the third floor. These quiet, distant pieces are scribble drawings made with graphite that bring a new level of depth to his work. Color bars have nothing on a spiral piece that appears to spin as it catches the light. NPR used the word “trippy” to describe the work on the third floor – it’s in motion, and it’s coming toward you.

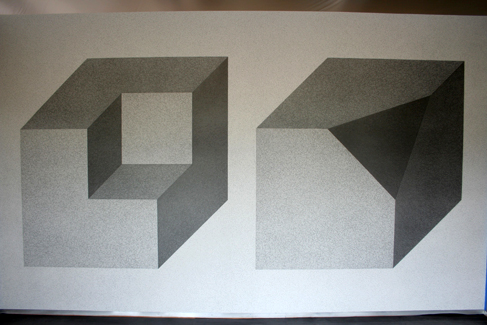

But a piece that stands out in the corner is Wall Drawing 1171. These is beside a few other graphite works that have no color, but add much dimension (this one can flip as you watch it).

The “cube without a cube” is a three-dimensional cousin of the earliest grey blocks, and in fact the earliest grey lines. It’s as though LeWitt found a favorite verb and conjugated it: grey line blocks, colored pencils block, dark acrylic wall blocks, bright acrylic wall blocks, graphite shapes block. I block, you block, we block.

I hadn’t realized I had soaked in LeWitt’s language until I browsed the website and stumbled upon the caption below Wall Drawing 38. This is an unusual piece, employing a pegboard wall to hold thousands of tiny rolls of colored tissue paper. These pieces were supposed to be put in at random, but anyone can imagine how difficult it is to generate a random pattern that appears random – surely the draftsmen had to touch it up, the way they touched up Wall Drawing 1121 (in the video above).

Additionally, this piece is set on three walls: the first wall has yellow and white paper, the second has white, yellow and red, and the third has white, yellow, red, and blue.

The website reveals that this piece was designed for four walls. The first wall had only white tissue. This is a piece that conjugates the block formation with a fresh medium, and a three-dimensional one at that.

In this case, LeWitt wants you to be inside the blocks (on the second floor) before he removes a cube from a cube (on the third floor, at the end of his life). He makes use of the wall space to trap you, to make you more directly involved with his experiments in color and space. I like this play upon the theme.

LeWitt wrote, “When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.” This exhibit was created by anything but machine. It takes real chopsticks to get those pieces of tissue paper in the peg holes. You the viewer are invited to simultaneously study the artist’s plan, and also the interpretation of each plan within the architectural space, the interpretation and choices of the artists LeWitt knew, and finally the labor of the people who put these pieces together. It’s a very active form of taking in art. You often hear people dismiss modern art because they feel they could have done a piece themselves. In this exhibit, it’s true, and LeWitt wants you to. Let me know if you have the time and energy to create a wall like this in your house. Really, I’d love to see it.

There is a nice piece in The Believer about following LeWitt’s instructions, and a photo essay of the pieces going up.

We were discussing in the Who Built America meeting the way that academics, historians, and writers – many people in the humanities – prefer to keep their work isolated prior to publication. It is supposed to have had some sort of immaculate conception; one cannot reveal the mistakes or the rough edges prior to the moment other scholars see it.

MASS MoCA does an extraordinarily good job of revealing the process behind the exhibit. You can see LeWitt’s transparencies as you enter the exhibit, you can watch videos of some of the pieces going up. You can view the whole exhibit online, by grid or by floorplan, or listen to the audio tour. You can begin to synthesize the work for yourself.

American Social History Project brainstorming

(Thanks for your patience – the blog is back!)

On Friday November 21st, we met with the American Social History Project and several historians to discuss the possibilities for collaborative learning in history. Attendees included Josh Brown, Steve Brier, Pennee Bender, Ellen Noonan, Eric Beverley, Manan Ahmed, Nina Shen Rastogi, and Aaron Knoll.

There was a general consensus that academics tend to resist the idea of collaboration (for fear they won’t get credit, and thus might not achieve tenure) and they prefer not to reveal their work in progress, instead unveiling it only when it achieves publication. There is a popular idea in academia that a single all-knowing expert is more valuable than a team of colleagues who exchange ideas and edit one another’s work. In the sciences, research is exchanged more freely; in the humanities, it’s kept secret. A published literary or historical work is supposed to be seamless. Nina mentioned that occasionally there is a piece published like the recent Wired interview with Charlie Kaufman where edits are visible (one story that keeps popping up in magazines is Gordon Lish’s edits for Raymond Carver). Bob stated that he believes we are on the brink of a whole new sort of editor, one who is recognized for excellent work when the edits she has made are available to readers.

Academics tend to see their goal as becoming the top scholars in their fields. One problem with this is that it limits their digital imaginations. If one becomes transfixed on becoming the single (digital) source for information of a certain subject, or even several subjects, the most one can build is a database. A compilation of such data is not synthesized. In a history textbook, one can read a single person’s synthesis of data. In the Who Built America? CD-ROM, one could view original sources as well as that a single person’s synthesis, so that one could decide whether that synthesis was any good. The group agreed that they do not want to eliminate the single thread of narrative that holds the original sources together, but they want to figure out a way to use the technology available to its fullest extent.

Another problem that attendees agreed this project would face was appealing to different pedagogical styles. If instead of standing before a class and giving a lecture with a bottom line, the teacher were to give students video, audio, and text that were from original sources, and ask them to do their own synthesis, this would be a completely new way to teach. The textbook exists to aid a teacher in presenting her own synthesis of the content. Some teachers will inevitably resist a change in their teaching methods. Ellen suggested this project may change pedagogy for the better. However, there is value for classes at, say, a large community college, in having a single textbook with concrete bottom lines in every chapter, but these will probably not be the market for our project.

Bob said Voyager was especially interested in producing the American History Project for CD-ROM because it was not a textbook, it was a book for people who like history. The AHP has struggled with marketing itself as anything other than a supplement to textbooks, and worries about losing something by slicing the content into chapters to fit the textbook format. The new project would face these same challenges. On the other hand, the AHP has had success especially with AP classes, and it may be possible to market to a small community of teachers who are interested in nonlinear learning.

We spent much of the meeting parsing the meta-issues of taking on networked textbooks, and we feel strongly that there is something to be gained from shifting our focus from “objective” history to participatory history, a history you can watch, break down, and join. Comment sections, links to related pages, and audio/video materials would enhance the new history project and enable students to better understand the process of how history is written. But most importantly, we want scholars and students to learn history by doing history.

Instant fix

Image inspired by Shepard Fairey.

In case you prefer to get your news online, here are a variety of ways to follow the election coverage.

Predictably, Twitter is following every second of the election. If you’re into Twitter, maybe you’ll also want to leave comments or videos for the site, “What would you say to the president?”

Homemade videos are linked to a map on Youtube’s Video Your Vote.

Google has created maps especially for the occasion. One nice pairing of video and maps allows you to track the locations of the candidates’ speeches, then watch them through Youtube. Justin Ward has also created a gadget for live election coverage.

I particularly like the Every Moment Now graph of article references for each candidate. Of course, there’s always FiveThirtyEight. You can also follow political headlines at Alltop. PBS’s Newshour is also online. (More links are available through 10,000 Words.)

By the way – to those who have been focused on following each step of this election, what will you read when the battle is over? Will you still check the news feverishly, or are you looking forward to spending your time in other pursuits?

Lauren Klein and The Turk

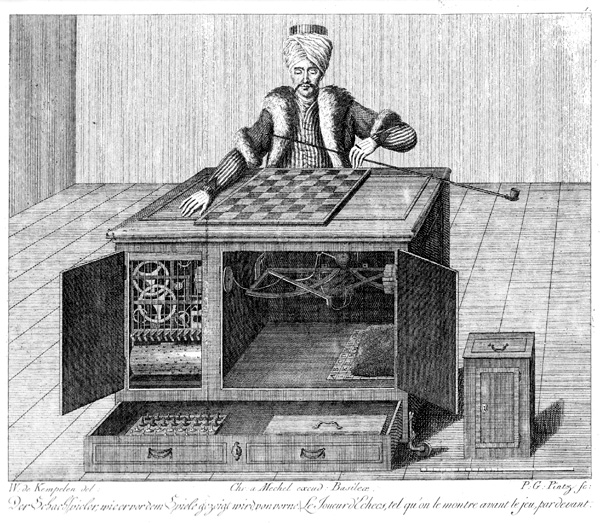

An engraving of The Turk from Karl Gottlieb von Windisch’s Inanimate Reason, published in 1784. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

We had Lauren Klein, a graduate student from CUNY, over to lunch this afternoon. One of the pleasures of such a lunch is later looking up conversational asides: today we happened upon the subject of chess machines. Lauren specifically referenced “Maelzel’s Chess Player” by Edgar Allen Poe, Edison’s Eve by Gaby Wood, and The Turk by Tom Standage.

The Turk is a chess-playing machine built in the 18th Century by Wolfgang von Kempelen. What made the machine so astounding was its chess expertise; of course, it was controlled by levers by a person beneath the chessboard, who moved pieces with its hands and could manipulate its facial expressions. The Turk was sold by Kempelen’s son to to Johann Nepomuk Maelzel, who added a voice box to the machine (to say “â?°chec!”) and used it to beat Napoleon, according to legend. The machine was eventually contributed to a museum in Philadelphia, where most of it was destroyed in a fire.

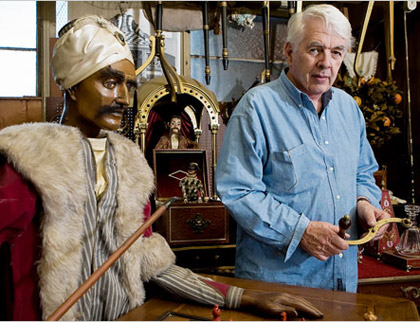

That is, until the pieces came into the hands of John Gaughan, the man who made Gary Sinise’s legs disappear in Forrest Gump and turned a beast into a prince for Disney’s Broadway production of Beauty and the Beast. He salvaged the remains of The Turk and built a version of it that is controlled by computer (for a price tag of about $120,000). As Poe puts it, “Perhaps no exhibition of the kind has ever elicited so general attention as the Chess-Player of Maelzel.”

Image courtesy of The New York Times.

Perhaps the most poignant theme of this story is that it strikes upon some of the things that draw us to technology: spectacle, surprise, a little hint of magic, and the humbling experience of being stumped by something that’s not human.

Greenblatt on human agency and New Historicism

Image via Queen’s University.

Here is a little bit about the MIT communications forum on October 14, with respondent David Thorburn, moderator Diana Henderson, and lecturer Stephen Greenblatt. Greenblatt is the Cogen University Professor of Humanities at Harvard. He co-founded the literary journal Representations and wrote the book Will in the World; he edits Norton Anthology of Literature and the Norton Shakespeare.

David Thorburn began the lecture by asking Greenblatt about an historical moment: his time as an undergrad- and graduate student at Yale on the cusp of New Criticism. Greenblatt listed his teachers, among them Harold Bloom, Jeffrey Hartman, and Robert Penn Warren. While New Criticism was the principle game in town, there was “something else stirring” in continuity with it. While defining New Criticism for his audience, Greenblatt referenced the W.K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley line, “Judging a poem is like judging a pudding or a machine. One demands that it work.” A poem was to be examined like a beautifully wrought object, or a verbal icon. Greenblatt recounted the feeling of empowerment New Criticism initially gave him: freeing him from a certain kind of “time-wasting and sociology,” and liberation from “a certain cult and taste.” You had to know how to “get your hands dirty, and learn what internal structures were.” And though he broke away from this school of thought, he said he is grateful to have experience with it.

Thorburn added that Greenblatt has the power of reading closely, even if he doesn’t read closely in the same way his mentors did; he still reads with “the rigor and excitement of the old New Critics.” Henderson added that this historical moment is an excellent time for criticism, since “attention to detail and method is very important with a glut of information.”

As for the “something else stirring,” Greenblatt said his thinking was affected by a “huge dose of Cambridge,” which was “curiously, not part of the New Criticism at Yale.” There he played a game where texts were passed around on scraps of paper and everyone in the room was supposed to guess when each text was written. It “seemed unbelievably stupid at the time,” but Greenblatt concluded that it was important to understand how a text fit into a specific historical and sociological moment. After a “mega-dose” of this, he came to understand the importance of thinking inside a text, rather than removing the text from its context (as in New Criticism).

Henderson concurred that delving together into the historical moment fosters a generosity of relationship between students and professors, a dialogue and openness “that allows you to not take umbrage,” and allows for “a kind of listening to student voices” instead of professors serving as “a kind of acolyte” and the students just taking notes.

Henderson said to Greenblatt, “Yours was a friendlier face of incorporating American and English thought at a moment of real culture wars.” [She was referring to the difference between New Historicism (a term Greenblatt himself coined for examining a text within the framework of history, culture, and sociology) and Cultural Materialism, a term for a branch of literary criticism stemming from Marxism that looks at a text not as an object, but as a process that is both politicized and historigraphical.]

Greenblatt defined a pivotal moment in his intellectual life: he read Althusser in the ’70s, especially the union of theory and practice, which opened his mind to how one could think differently of culture and society. This was a “brilliant continuation of hermeutic thought and New Criticism,” which worked to align what he thought he’d learned with what was (then) going on in France.

Thorburn quoted Greenblatt back to himself, saying, “This is what was going on when I found my voice.” Thorburn asked Greenblatt to expand upon this statement.

Greenblatt said that it was clear in his writing, in his style, that he was not an apprentice any longer. “Things holding you [down] disappear: you’re not worrying what your advisor thinks.” Instead Greenblatt began to wonder, How could I think out of the model of an individual life?

He wrote a book about Sir Walter Raleigh, which he explained was about this. Raleigh was a soldier, explorer, scoundrel, courier, an interesting poet. He was not simply defined by his work as a fiction writer or a critic or a professor. Greenblatt pondered Raleigh and himself, what their identities were, what their subjectivities were. He asked, “What would it mean not to think so conventionally about a life? What would it mean for me to have a voice?” He felt “liberation to think in a life, passionately, his life and my life… not to throw one away and not think about the other one, but not to be stuck in the biographical model of an individual life.”

Henderson added that the great question, then, was how to use history to tell a story. At the moment that New Historicism emerged, it put the individual back into the system (as opposed to high theory and Cultural Materialism). It was about America in individual lives.

Greenblatt agreed, “It was a great moment, an unbelievable moment… the question was how to sound like who you are.”

Henderson said, “And that’s where history comes into play: in who YOU are. It is a unit of rhetoric, organizing history, you sort of grab something that for you resonates and tells a vivid story… of course, [grabbing one story and not another] immediately begs the question, why not this one instead?”

Greenblatt proceeded with a vivid story of his own: when he finished his Raleigh book, he sent the manuscript to Oxford University Press. There a woman named Agnes Latham, who had worked all her life studying Raleigh (the culmination of which was a single article). She read his work and suggested that after 20-25 years perhaps Greenblatt would know enough about Raleigh to write about Raleigh. “That vision of how to do this work, to know absolutely every detail about someone’s life… seemed to me a form of intellectual deadening.” He remembered a professor who wrote on Hardy, who was afraid of publishing in case he discovered something else about Hardy. As a scholar, Greenblatt advised, decide when you have to cut yourself off; later you may know more but won’t end up saying much more. You have to know when to stop. He said he had to learn for himself and his students to be responsible, but not to be so obsessive or so frightened. You must shape around the idea that you have a story to tell, for yourself and your readers.

Thornburn reiterated that there are a few key terms in New Historicism that are problematic and central in Greenblatt’s work: human agency and self-fashioning. He asked Greenblatt to elaborate on these.

Human agency and self-fashioning are terms “like fate and free will: the more general they are, the gassier they are.” Greenblatt responded with an anecdote from a trip to Israel: he traveled to give a lecture, and on Friday night, someone invited him to have dinner at their house in the old city. After dinner, they sat on the roof under the stars and sang the Hebrew prayers traditionally sung after meals. Greenblatt doesn’t think of himself as having much of a spiritual life – his exact term for his perception of Jewish tradition was “total flapdoodle” – but he had a powerful semitic reaction to this. He said being Jewish in this scenario was about non-agency; it was uncontrollable, like getting an erection at the beach. There was something about “the words that you sing as a child, that you don’t believe in… I was already way post-belief, but still affected.” And yes, agency became a part of it – he felt the urge to ask, “Christ, what’s that about, and what am I going to do about it?” He said, “I didn’t know what to do with it; I was amazed by it.” All Saturday afternoon, with sounds of helicopters overhead, he thought about how to parse his experience. He chose not to ignore it, and met a friend at the PLO to talk it through; in this moment he chose agency over the alternative. He spent a lot of time trying to think who he was, what historical situation he was in, and why these things made him want to meet at the PLO instead of going elsewhere, instead of being swung around on a string, “and that’s what I’ve been interested in all my life.”

Thorburn added here that one of Greenblatt’s strengths is “this dividedness in him.”

Henderson expanded upon Greenblatt’s example, pointing out that we must identify local choices, the effect of those choices and what difference they make, and finally, “how do we tell our own story and the history of the world in a way we think matters.” We must consider the value of our storytelling, and “our obligation to whatever It out there is.” Henderson said it seemed to her that only half of it is agency.

She then brought up the subject of this lecture, the place of the book today, and posited, “Can we consider the place of the book today?” Greenblatt interjected, who are we to consider the place of the book today? Henderson said considering the students in front of her, “And as scholars, what are we asking of our young now? We’ve gone to another extreme because we’re trying to get things out NOW? In another system that doesn’t want to publish your book.” This sense of immediacy seemed out of place to Henderson in the current publishing world.

Greenblatt continued to say that last year Harvard passed a vote that faculty would be required if they wrote an article to allow access to a digital version for Harvard, so that all their scholarly work would be universally accessible digitally. “As a general principle, the idea that the work that we do should have value digitally and have universal access,” is what Greenblatt said he had been calling for for years. In an article for the MLA, he said we must transform our understanding of what it means to appear on the web and how we can use that. We must make more broadly accessible our work. We must feel that work is significant; though the web must take into consideration the feeling of community that is subscription-based. You feel you are part of a community when you subscribe to a scholarly journal. But ultimately your work can reach a larger scholarly audience with the internet.

A grad student with blonde dreadlocks asked a question about Jane Newman, pastoral conventions, and bringing history back as an objective field. Greenblatt replied, “I don’t carry a card in my wallet that says Official New Historicist. On the whole… making old and new historicism live again… it does very good archival work, sociological work, has very little relation to [objectivity.]”

The example he put forth is whether Shakespeare was Catholic. “I just think the work is not pious… I think it’s actually quite secular.” It is “manifest in a lifelong grappling with Christianity and Catholicism.” In Greenblatt’s opinion, Shakespeare had an interesting engagement with religion, but there is inadequate evidence to support either theory. One can examine Shakespeare’s father’s will, his mother’s relationship to the Arden family in Birmingham, and the people who educated Shakespeare. “Can I prove anything? No. But I thought it was interesting to tease out [these elements.]” Another example: Was Donne tormented all his life? Greenblatt says he thinks Donne is definitely interested in “damaged institutional goods,” and he drew upon the aesthetics all his life because he probably had personal relations to them, but we don’t know whether he actually had personal relations to them or not.

A man in the audience inquired about the state of culture. Greenblatt responded, What if, for example, Nomads or exchange or exile were actually the “normal state” of culture, rather than that of settled cultures? What follows from that? What if we think about cultures in movement? Greenblatt wanted to try to think about a new set of terms – e.g. culture is essentially about movement. Or, Greenblatt insisted, this could go in a second direction: the weakening of the boundaries between art-making and criticism. In one’s pedagogical practice, this means getting more interested in relation to the makers. Academics are in the habit, Greenblatt said, to refuse absolutely everything the makers say – not only what they’re up to, but their relation to art-making (this stubbornness is consistent with Greenblatt’s assertion that professors’ work is driven by students even though one doesn’t admit it). With new technology, it’s possible to make things in interesting ways – certainly visual things – that couldn’t have been made five years ago, certainly not 20 years ago.

For example, Greenblatt said, look what Shakespeare did with his citations: he was famous as a thief. “What happens when he steals from other people, what does he do with the materials? What happens if you don’t imagine that the fate of all these objects was to fall into Shakespeare and end there? They don’t end there.” Henderson agreed. They have metamorphic effects. Greenblatt is interested in experimenting with that idea intellectually, aesthetically, and in following moving cultures from place to place.

Henderson added that the materials do not end with Shakespeare, because Shakespeare is being performed and reimagined all of the time. Performing Shakespeare made people in the humanities aware again that they need to talk to the makers.

An older man on the stairs asked for Greenblatt’s take on Israel.

Greenblatt responded to an issue that is specific to Harvard. In his opinion, John Pullman said things that were extremely foolish to say. Therefore Greenblatt thought that though many people didn’t want him to, he should come as a poet to Harvard and people should give him a hard time. Rescinding the invitation seemed foolish, but protest seemed appropriate (and wouldn’t require the university to support the West Bank Settlements).

A man in the audience asked if there are moments in scholarship that are like the security gates at airports, that you can go in but can’t go back out. He gave the Greeks vs. the Romans as an example.

Greenblatt said he would love to say that groups in conflict will just work things out, but that this is untrue. Catholics and Protestants, for example, are two factions that couldn’t “settle it.” Epicurianism, which is Greek organization, survives because a Roman poet wrote a fantastic poem that survived, and in the Middle Ages, was found. “My sense is that there’s no getting back to the thing itself. But to give up the dream completely – that all we have is what the clerks have given us – is a depressing historical position. All my life… gives me the illusion that I’m finally getting it.”

Greenblatt launched into a description of Richard Madox’s diary. His recounting of the book went something like this: Madox wanted to go on “an insane voyage to the new world.” But he quickly realized “he hated every sucker on the ship.” Madox was a very finely educated, rather sophisticated guy, and he was stuck on board with “a bunch of horrible yahoos.” So in his diary, he gave them Latin and Greek names, and invented his own code to complain about them freely. Madox died off the coast of Brazil, and the others brought his diary back because they didn’t know what was in it. When Greenblatt read this book, he felt he was finally reading “a voice that hadn’t been mediated in fifty thousand ways.” It wasn’t the product of German Romanticism.

A woman asked Greenblatt to reflect upon Amitad Ghosh’s In An Antique Land. Greenblatt replied that the book is an important touchstone, it articulates problems, but literal travel isn’t recorded in a book. Even the digital world of literature doesn’t solve this problem. Literal travel is a crucial element, he continued – who are the customs agents, what do you have to pay, what do you have to conceal? There is a huge amount of material of this kind. And that literal travel becomes the metaphorical. (He is now in his classes at Harvard incorporating a simulation of that sort of travel with digital resources. One such course is “Travel and Transformation in the Early 17th Century.”) In a play like King Lear, Greenblatt said, you have “a crazy pastiche of things”: Isaiah plus Sir Philip Sydney mixed up with Machiavelli. Each carries with a it a set of implications through its (physical) travels.

A woman in the audience asked for Greenblatt’s take on the “what if,” or the imagination, and also to discuss the relationship between hypothetical and historical in his work.

Greenblatt employed the example of Natalie Zemon Davis’s Fiction in the Archives, which allowed for people to think about why people were writing the things they were writing instead of concentrating on the truth contained therein. Greenblatt argued that there is an extent of imagination and making up already implicit in the materials that we use. We are saturated with “crazy conjectures” of people who left traces of themselves. It is even more difficult to work with fictional materials, which are full of imaginary conjectures. You must account for the fact that you are deploying imagination yourself as you study it.

“On the other hand,” Greenblatt said, “You can’t just make it all up.” For example, one could use the discourse, “I never thought of anything I wrote as ‘fiction,’ ” but I am interested in effect and affects that are reachable through the imagination to get them in play. “You cough when the story is over if you’re not using the imagination.” In Anthony Burgess’s Nothing Like the Sun, though, there is a difference in the game being played. There is a tiny hook of documentary evidence to begin delving into the story. As a reader, perhaps it’s best to assume Shakespeare made up from stuff he could draw on from his life, not one character he is trying to portray from his life. This is better described as something else, like literary biography.

Henderson concluded, “Doesn’t it just come back to, What did Shakespeare say, anyway?”

Greenblatt laughed, “He’s a wonderful broken field runner; you can’t catch him that way anyway.”

Thorburn handed Greenblatt a copy of a book he published 25 years ago. Greenblatt read aloud the introduction, a story of a man on an airplane who asked Greenblatt to read the words, ‘I want to die, I want to die.’ The point of this fragment is that Greenblatt chooses the moments in his life when he recites someone else’s words. (Ironically, Thorburn had chosen this moment for him.)

Greenblatt ended the talk by saying, If you could record every movement of every atom as the world was constructed, it would become clear there was no free will, but it would also be clear that “one atom swerved.” That swerve was ridiculed for decades – it was written in 1417 by Lucretius. Now it is “the only thing in contemporary physics that seems kind of hip.” In other words, generations of theologians ridiculed the thing that saved agency.

How do you want to read?

(Photo of Tom Stoppard’s book case, made by T. Anthony, via The New York Times.)

For the sake of travel and convenience, sure, even a Kindle is better than toting a book shelf with you on an airplane. But people still resist eReaders. Is it because eReaders cannot meet your reading needs, or because they’re unaffordable and inelegant?

The media is brimming with iPhone and Android apps and speculations about eReading. Even literary blogs are tech-focused: Maud Newton dropped her iPhone in the subway, but didn’t lose her place in her virtual book. And Chad W. Post ties up last week’s “end of publishing” coverage with highlights from New York Magazine‘s comments (most of them are much more positive about eBooks than New York Magazine).

eReading devices haven’t made an Android-esque debut, but they’re chugging forward. Forbes presents a $850 iRex reader with a 10.2 inch screen. Plastic Logic has produced a one-pound, flexible eReader without Wi-Fi or backlighting (it looks sort of like one of those plastic covers Calvin put over his “Bats Are Bugs” report in the Calvin and Hobbes cartoon). The phones still have a leg up on these devices because they have names and color screens and do not cost $850.

The Sony eReader has been said to be difficult to navigate. [Edit: the new one has just been released.] The Kindle is distracting. And the iRex has received criticism from USA Today for a short battery life, slow loading, and incompatibility with Windows. In other words, eReaders exist but no model has achieved ubiquitousness; those that have managed to draw an audience are still clunky, slow, and don’t have enough memory for major personal libraries. Until we all start to feel tech-lust, let’s ignore these beasts and discuss something more important.

How do you take your eBooks? You can turn pages in Scribd’s “Opening Up Education,” or scroll down through Hewson’s newA Season for the Dead. You can also scroll through scores of poetry at BlazeVox or Cory Doctorow’s new book, Content. You can read Warren Ellis’s comics online each week, or pay for them to be printed on dead trees. Do you want to read books in blogs embedded by Google, or perhaps on your iPhone? Here are a few questions:

1) Is it more convenient in a pocket-sized device like one of these phones, a Kindle-sized screen, an iRex-sized screen, or a desktop screen? Are you inclined to stick with paperback-sized pages when you read an eBook?

2) Are there certain types of books you would read on one screen rather than another? I assume there are – do you use The Pynchon Test or some other method to determine the best possible reading device for your material?

3) Are there certain features in one of these that really works for you? Specifically, do you care about turning the pages? Scrolling? Reading inside or outside a browser?

4) Do you feel more compelled to buy a digital book if it is scarce? Libraries seem to be wondering whether to loan one ebook out at a time, or take advantage of the infinite resources the digital world provides.

5) Is the problem that screens are too closely associated with your workplace, and that you’re afraid of your reading being interrupted by popups, email, etc.?

6) Most importantly: Is there some mysterious intangible thing that books have and eBooks don’t? If so, can you describe it? (That library smell and your great-grandfather’s marginalia in your prized first-edition don’t count.)

There has been a little buzz about this this week, and I’d like to challenge if:Book readers to contribute to the dialogue.

Bob recently mentioned that he is puzzled as to why people are willing to have music on iPods and movies on their laptops, but feel skeptical of books on a screen. His point was that these other events are very social; one hears music at concerts and sees movies in theaters, but reading is the most solitary of these events and seems the easiest to move from paper to eReader. Dan Visel has posted on the beauty of the “pause” button. “Pause” converted films – which one cannot control in a theater – into something the user could control thoroughly. And it seems to me that perhaps we are resistant to converting to a user-driven form when the form we have is already user-driven. But if it were done well, would you read it?

I read an article this morning that suggested eBook culture would provide publication space for things that don’t deserve to be published, but if talented publishers are able to aggregate eBooks, we may be able to worry less about this problem (it would also benefit the publishing industry as a whole to cut down production costs, and would potentially provide for “risky” decisions – supporting new literary writers, for example, or books of short stories).

So lifting our heads above all these doubts: Is it a control issue, a content issue, or an aesthetic one? Or something larger about the way we connect to digital literature?

How do you connect to literature today? And how could you better engage with it?

Synthesizing art, literature, and Halloween costumes

Natura Morta, Giorgio Morandi, 1956 (via The Met)

There is little or nothing new in the world. What matters is the new and different position in which an artist finds himself seeing and considering the things of so-called nature and the works that have preceded and interested him.

-Giorgio Morandi, written in 1926, published in 1964

Morandi exhibits have popped up all over the city: in the Met, Lucas Shoorman’s, and Sperone Westwater (thanks, Dan). I attended the Morandi exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art this weekend. While the Met presented him on paper as a quiet and introverted artist (they even had a quotation about how he was a testament to what you can find when you look inside yourself), the most striking quality of this collection is how much he was influenced by outside sources. His brush strokes grow agitated and thick in one oil painting, then light and Cezanne-like in the next. He has watercolors and charcoals and experiments with shadow and light. He has a series of cubist still lifes. But the subject matter hardly changes: it is almost always a white vase or a stack of bowls in muted colors. It is as though he spent his whole life trying to see the same objects in a thousand different ways, borrowing eyes from his friends when he needed them.

Reading is not much different than that. We are reading so in hopes of seeing a fresh take on the same old, same old. Occasionally readers pay homage to the story by passing it on, verbally or musically or artistically.

In “The Ecstasy of Influence,” Jonathan Lethem describes receiving a copy of his own first novel as a gift. Artist Robert The had cut Gun, With Occasional Music into the shape of a pistol. Lethem was charmed by this reincarnation of his work. “The fertile spirit of stray connection this appropriated object conveyed back to me – ?the strange beauty of its second use – ?was a reward for being a published writer I could never have fathomed in advance. And the world makes room for both my novel and Robert The’s gun-book. There’s no need to choose between the two.”

When I met Margaret Atwood last year, she said she has been pleased with the things she had inspired others to create. “Your work gets away from you and takes on a complete other life. People go to Halloween parties dressed as the Handmaid’s Tale,” she said. “I am very much not against it.”

“Who Built America?,” software published in 1991 that I previously blogged about, uses a word instead of a “back” button. The word is “Retrace.” I think this is a lovely precursor to the modern arrow. There is an art to the way we retrace each step of a book’s life. Stories are often recycled, and we can understand them when we understand the way they were cut and tailored by each author. Both Lethem and Atwood embrace the idea that their work will take new form beyond their words – and that this is a compliment.

If nostalgic cartoonists had never borrowed from Fritz the Cat, there would be no Ren & Stimpy Show; without the Rankin/Bass and Charlie Brown Christmas specials, there would be no South Park; and without The Flintstones – ?more or less The Honeymooners in cartoon loincloths – ?The Simpsons would cease to exist. If those don’t strike you as essential losses, then consider the remarkable series of “plagiarisms” that links Ovid’s “Pyramus and Thisbe” with Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and Leonard Bernstein’s West Side Story, or Shakespeare’s description of Cleopatra, copied nearly verbatim from Plutarch’s life of Mark Antony and also later nicked by T. S. Eliot for The Waste Land. If these are examples of plagiarism, then we want more plagiarism.

-Jonathan Lethem, “The Ecstasy of Influence”

As Johanna Drucker calls it, the “e-space of books” – the space in an author’s brain that we have the privilege of exploring through the text – is under-served by the printed page. In a way, the works that have been plundered will have the chance to be credited again. Why not link from Ovid to Shakespeare to The Simpsons? Why not allow the worlds that exist in e-space to nestle into the archives of cultural consciousness?

I’m a very greedy reader. I want more of everything: I want to know how the literature is related to current events, how it’s perceived by critics, who helped to edit the book, who the author’s friends were, who was writing upon a similar theme at that time, whether the fiction is grounded in fact, and what other readers thought of the ending. To my delight, plenty of readers have usually broadcast their thoughts in a dozen formats.

It’s hard to stay in print or on television for more than a minute, but entering readers’ minds is a very real way to stay alive. While the doom and gloom of recent articles has made it sound like readers are on the verge of extinction, we could scarcely be further from it.

In fact, we are more literate, more capable, more connected, and more potentially engaged than at any time in human history.

–Mark Bauerlein

Imagine for a moment the possibilities a story might present. Cain and Able alone could lead you to the Wandering Cain of Mormon folklore, to 15C representations of the characters, to the history of martyrdom, to Lord Byron’s poem “Cain,” to John Steinbeck’s East of Eden, to Neil Gaiman’s Sandman series, to Bloc Party’s “Cain Said to Able” and Bruce Springsteen’s “Adam Raised a Cain,” to the Simpson’s clip of the Flanders kids playing Cain and Able in a home movie. This is a copyright nightmare, but sometimes authors have to let go. Otherwise they’ll never see people at Halloween parties dressed as their characters, and they’ll never allow themselves the breadth of information available with this kind of free exchange.

But Morandi’s work benefited from the network of visionaries he knew. Without them, all he had was a white vase. Networked books aren’t a new concept, they’re just a new way to display the relationships between texts and other media.

There has always been a network in art and storytelling. And that network doesn’t fit cleanly between two covers.

History is written by the readers

Pardon me for plagiarizing Churchill, but the victors aren’t the only ones writing history these days. At the Institute, we’re re-imagining the American History Project’s “Who Built America?”, hoping to re-imagine the sort of information in this CD-ROM from 1991, converting now into a more malleable form. Dan Piepenbring blogged about this as well. The CD-ROM, as a point of reference, is impossible for us to go in and edit or update. What was there in 1991 is there today; it’s stagnant.

A networked history book changes everything. We are moving past the pretense of a single objective history, and moving into a discourse constructed by historians, teachers, and students. It has been said that to study history is to participate in it. We can add another layer of truth to this: those who study history will simultaneously write history. As they read, they may add links, annotations, comments, etc. Wikipedia has done this, but not in such a way that it is trusted as an academic resource. We need to blend the prestige of historians and the wealth of available original sources into a multimedia form that is easy to navigate and change.

This is beneficial because history books are so quickly outdated; history is happening, well, every minute, and of the millions of news stories published daily, each one has archiving potential. And our hunger for analyses of everything that’s happening has never been more important. No one can navigate through all of the information of The Information Age on her own; editors and shared links are essential. Newspapers are supposedly dying, whereas the demand for subjective accounts of news (blogs, etc.) is thriving.

What “Who Built America?” does best is linking sections of the book to original sources. Where a textbook may say, “Frederick Douglass was a great orator,” the networked book can present audio clips from Douglass’s original speeches. The reader will ostensibly conclude that Douglass was an orator, but the reader comes to this conclusion herself rather than trusting the author’s adjective choice. While one could always formulate a case for some sort of bias based on the limits of the audio clips available and those the editors of the network book first choose to present, dissenters would have their own say in the comment bar. If a book is linked to internet sources supplied by readers, there would be limits to what is presented but not many. Like Wikipedia, one could never sit down and read all available information in a single day.

And rather than sitting down to read the material in a linear way, the reader could zip from one medium to the next, perusing many areas of interest simultaneously.

The power of synthesizing these media is that one can study history through Hemingway’s letters and Zora Neale Hurston’s first short story, through Charlie Chaplin films and “The Birth of a Nation,” through Woodie Guthrie songs and FDR’s fireside chats. With scholars’ input, we could view these simultaneously through a kaleidoscope of critical lenses. It’s like opening many tabs within the browser of your brain. And far from “making us stupid,” the diversity of perspectives and formats ought to enrich our comprehension of the material.

We read history because the range of experiences we have in one life is never enough to teach us what we could learn in a thousand lives. Reading in a networked format requires a similar humility.

As Bob asked recently, what does an editor do in this brave new world? Let’s assume for now that there is a single person monitoring comments and links. The role of the editor, then, is to aggregate scholarly references and call the reader’s attention to the most germane comments. I think there is a market for this: a trustworthy source is worth an investment. (Perhaps this is not true of everyone, but I find myself inclined to buy wine from the shop-owner who can tell me what will compliment exactly what I’m having for dinner that evening; I like to tell my haircutter that I have an interview and a vacation coming up, and let her decide what style is both easy to maintain and professional-looking; I talk to people in bookstores who share favorite fiction writers so that I can get their recommendations before I purchase something. Kevin Kelly is right. Technology like this may be viable if it’s done in a personalized and findable way. There are many types of readers, and with more media available to them, we can cater to the needs of casual readers as well as serious academics. Schools are laden with both. This raises an issue of how we best suit the needs of each reader, but that will have to be borne of a dialogue with the readers in question.) It may be that the editor’s task is simple: to listen to the readers, and mediate conversations they want to have with one another inside the text.

Because we the readers are limited in time and space (such a pesky bug in the network of the universe), we will presumably edit and annotate differently as time moves forward. We will have to account for these contradictions; truth is a slippery thing. Right now a book exists within a liminal space, and history books are able to ascribe a narrative to the information they present. But that backbone of literature will have to stretch and curve when symbols and events are constantly changing, and when we are constantly changing our minds.