I spent the past weekend at the Fourth International Conference on the Book, hosted by Emerson College in Boston this year. I was there for a conversation with Sven Birkerts (author of The Gutenberg Elegies) which happened to kick off the conference. The two of us had been invited to discuss the future of the book, which is a great deal to talk about in an hour. While Sven was cast as the old curmudgeon and I was the Young Turk, I’m not sure that our positions are that dissimilar. We both value books highly, though I think my definition of book is a good deal broader than his. Instead of a single future of the book, I suggested that we need to be talking about futures of the book.

This conciliatory note inadvertently described the conference as a whole, the schedule of which can be inspected here. The subjects discussed wandered all over the place, from people trying to carry out studies on how well students learned with an ebook device to a frankly reactionary presentation of book art. Bob Young of Lulu proclaimed the value of print on demand for authors; Jason Epstein proclaimed the value of print on demand for publishers. Publishers wondered whether the recent rash of falsified memoirs would hurt sales. Educators talked about the need for DRM to encrypt online texts. There was a talk on using animals to deliver books which I’m very sorry that I missed. A Derridean examination of the paratexts of Don Quixote suggested out that for Cervantes, the idea of publishing a book – as opposed to writing one – suggested death, perhaps what I’d been trying to argue last week.

Everyone involved was dealing with books in some way or another; a spectrum could be drawn from those who were talking about the physical form of the book and those who were talking about content of the book entirely removed from the physical. These are two wildly different things, which made this a disorienting conference. The cumulative effect was something like if you decided to convene a conference on people and had a session with theologians arguing about the soul in one room while in another room a bunch of body builders tried to decide who was the most attractive. Similarly, everyone at the Conference on the Book had something to do with books; however, many people weren’t speaking the same language.

This isn’t necessarily their fault. One of the most apt presentations was by Catherine Zekri of the Université de Montréal, who attempted to decipher exactly what a “book” was from usage. She noted the confusion between the object of the book and its contents, and pointed out that this confusion carried over into the electronic realm, where “ebook” can either mean a device (like the Sony Reader) or the text that’s being read on the device. A thirty-minute session wasn’t nearly long enough to suss out the differences being talked about, and I’ll be interested to read her paper when it’s finally published.

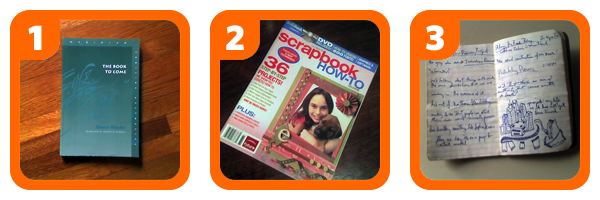

As an experiment paralleling Zekri’s, here are three objects:

There are certain similarities all of these objects share: they’re all made of paper and have a cover and pages. Some similarities are only shared by some of the objects: what’s the best way of grouping these? Three relationships seem possible. Objects 1 & 2 were bought containing text; object 3 was blank when bought, though I’ve written in it since. Objects 2 & 3 are bound by staples; object 1 is bound by glue. Objects 1 & 3 were written by a single person (Maurice Blanchot in the case of 1, myself in the case of 3); object 2 was written by a number people.

If we were to classify these objects, how would we do it? Linguistically, the decision has already been made: object 1 is a book, object 2 is a magazine, and object 3 is a notebook, which is, the Oxford English Dictionary says, “a small book with blank or ruled pages for writing notes in”. By the words we use to describe them, objects 1 & 3 are books. A magazine isn’t a book: it’s “a periodical publication containing articles by various writers” (the OED again). This is something seems intuitive: a magazine isn’t a book. It’s a magazine.

But why isn’t a magazine a book, especially if a notebook is a book? If you look again at the relationships I suggested between the three objects above, the shared attributes of the book and the magazine seem more logical and important than the attributes shared between the book and the notebook. Why don’t we think of a magazine as a book? To use the language of evolutionary biology, the word “book” seems to be a polyphyletic taxon, a group of descendants from a common ancestor that excludes other descendants from the same ancestor.

One answer might be that a single issue of a magazine isn’t complete; rather, it is part of a sequence in time, a sequence which can be called a magazine just as easily as a single issue can. I can say that I’ve read a book, which presumably means that I’ve read and understood every word in it. I can say the same thing about a particular issue of The Atlantic (“I read that magazine.”). I can’t say the same thing about the entire run of The Atlantic, which started long before I was born and continues today. A complete edition of The Atlantic might be closer to a library than a book. Or maybe the problem is time: the date on the cover foregrounds a magazine’s existence in time in a way that a book’s existence in time isn’t something we usually think about.

To expand this: I looked up these definitions in the online OED, where the dictionary exists as a database that can be queried. Is this a book? I have a single-volume OED at home with much the same content, though the online version has changed since the print edition: it points out that since 1983, the word “notebook” can also mean a portable computer. My copy of the OED at home is clearly a book; is the online edition, with its evolving content, also a book? (A stylistic question: we italicize the title of a book when we use it in text – do we italicize the title of a database?)

We’ve been calling things like Wikipedia, which goes even further than the online OED in terms of its mutability over time, a “networked book”. But even with much simpler online projects, issues arise: take Gamer Theory, for example. If much the content of what appears on the Gamer Theory website appears in Harvard University Press’s version of the book, most people would agree that the online version is a book, or a draft of one. But what are the boundaries of this kind of book? Are the comments in the website part of the book? Is the forum part of the book? Are the spam comments that we deleted from the forum part of the book? This also has something to do with Bob’s post on Monday, where he wondered how sharply defined the authorial voice of a book needs to be to make it worthwhile as a book.

What we have here is a language problem: the forms that we can create are evolving faster than our language – and possibly our understanding – can keep up with them.

Trying to define what is a “book” (and similarly what is an “ebook”) is like the recent exercise by astronomers to define “what is a planet.” Collectively, we intuitively know the general parameters of what constitutes a “book” — both the physical object and the nature of the content. But trying to exactly define it is elusive. This reminds me of the famous quote by Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart who once wrote that “hard-core pornography” was hard to define, but that “I know it when I see it.”

I prefer to use the phrase “digital publication” since I am finding the fuzzy boundaries which exist in the paper world between books, newspapers, magazines, etc., are getting even fuzzier. And using this phrase is freeing. For example, my colleagues in IDPF who are maintaining the OEBPS Specification still have difficulty grasping that textual content can actually be highly non-linear despite using the Web everyday — they want to shoehorn digital content into a linear form. In the OpenReader Format specification, a next-generation XML-based framework like OEBPS, the focus is on representing most types of digital publications. This has resulted in enabling mechanisms to handle highly non-linear content (such as web-type content and hypertext fiction) in addition to highly linear content characteristic of many books.

dan,

fantastic post. I’ve been thinking about the boundaries of networked books, especially in regards to lapham’s quarterly, and the notion of a quarterly magazine–which is somewhere between a magazine and a book–and its online component, which can spiral on endlessly. What I have been wondering is if there is some notion of openness that isn’t strictly related to form–Umberto Eco wrote about it in the seventies. My concern is that there is a particular type of work that is suited, formally, for networking, and other work (like fiction novels) that isn’t.

But then there are works that seem to cross the line or transcend the boundaries. Harry Potter, for example, jumped straight off the page and onto fan sites. Borges seems like another candidate; his fiction makes my mind spiral out into the world. I find my mental attachments loosened, and a rush of ideas come in to fill the enlarged space.

These books, then, represent something that can be explored and built on. Lapham’s Quarterly will almost certainly be the same thing. I think we will probably define the boundaries quantitatively, by making things. Some will succeed and others that fail. The differences will eventually be codified in common practice and we’ll have a new corpus to describe. We’ll invent the vocabularly then.

Very interesting post. I noticed one statement that seemed quite unusual to me, and I felt the need to comment. You wrote, “Educators talked about the need for DRM to encrypt online texts.”

I am very surprised that educators would support DRM technology, when it has been identified by many educators and librarians as hampering effective and legal use of copyrighted materials. For instance, take a look at this publication from the Berkman Center for Internet and Society,

The Digital Learning Challenge: Obstacles to Educational Uses of Copyrighted Material in the Digital Age.

The use of DRM is clearly indicated as a top obstacle in education.

I’d be interested in learning more about the reasons an educator would support technology that, to my knowledge, only hampers the fair use of copyrighted materials in the classroom.

all this time you’ve been talking about “books”,

and you just now realize the term is overloaded?

i thought we established that over two decades ago,

and agreed to phrase our points carefully to indicate

unambiguously what meaning we’re using at any time.

no wonder this often seems like a merry-go-round…

-bowerbird

James, I was as surprised as you, but that’s what it was – educators trying to figure out ways to make systems they could lock down. Educators complaining about DRM were there as well, of course.

Bowerbird,

I think we realized this a long time ago and have been searching in vain for a replacement for the term ‘book’; until we have something that describes the never-ending, ever-growing, continually shifting multimedia document, then we’re sticking with book, as overloaded as it is.

However, many other people involved in the discussion haven’t entirely let go of their own notions of book – nor should they. ‘Book’ has always been a flexible term, and while we’re not sure that it will stretch to encompass the documents we’re talking about, it is possible.

I’m sure you’ve realized that any human conversation (spoken or written) is full of undefined terms, and full of assumption. That is part of the beauty of human communication. But the merry-go-round doesn’t just move in circles – it ever so slightly advances. The terms of the conversation are changing, but slowly. So please, be patient.

i’m an old man, jesse. :+)

i don’t have time to “be patient”.

especially if it means rehashing stuff

that i stepped around 2.5 decades ago.

and let me tell you, you don’t want to

wait until you’re an old man for all of

this exciting stuff to happen either!

so move things forward! and fast! :+)

-bowerbird

Thanks for such a provocative post Dan. It’s really interesting how our posts seem to be covering a lot of the same questions from such different angles. Here’s something Ben wrote yesterday for a report we had to submit to a funder. I love the concept of the book as a “shapeshifter ”

Lets say that regardless of the different reading actions associated with attentive consideration of a comic book, an 18th century almanac or a 20th century scrapbook, that all are still considered books. But then attentively look at these objects in a mirror. Would you describe their reflection in a mirror as a book? If not then it is inappropriate to term their simulation on a screen as a book. And if facsimile book images on a screen are not a book it may be premature to classify other on-line genres as books.

Maybe its better to consider screen presented works as documents. David Levy considered this a better inadequate term. A wider term would be something like a “readable”. There really is no requirement that books be a genre of screen presentation. In such as context the future of the book would be exactly that; the prospects for print. The book of the future (a non-paper medium) as a projection could then be set aside. Let’s not confuse the two.

well, no better representation of the overloading

than the juxtaposition of the last two comments, eh?

gary focuses exclusively on ink-on-paper, and

bob talks of content shapeshifting in containers.

nor is it the case that everyone at the institute

always speaks clearly using bob’s definition,

or ben would never have said “ebooks are dead” —

/blog/archives/2006/09/phony_reader_1.html

— let alone said it repeatedly, when what he was

_really_ saying is that approaches toward e-books

that rely on handheld _dedicated_ machinery are

doomed to failure in the always-connected world

we’ll soon have with pint-sized full-on computers,

a dead-end like the old dedicated word-processors.

if you ask me, the book is the content. period.

an e-book is an electronic representation of it.

but hey, it doesn’t really matter how i define it.

or how gary defines it, or bob or ben define it.

because the term will _always_ be overloaded…

so when we discuss, we have to be _clear_ about

the particular aspect to which we’re referring.

and we can’t let anyone use sloppy terminology.

but as i said, those of us who’ve been thinking

about electronic-books for over 25 years now

came to that bright realization 25 years ago.

i’m sorry if we didn’t clearly communicate that

to all the newbies who’ve “discovered” e-books,

but really, folks, there’s nothing to see here,

so please move on…

-bowerbird

One of the most exciting things about reading the if-book blog is to be part of a conversation where people are pondering seriously not only on how to implement the vessel that will hold an elusive contents –one that we are still unable to name– but also reflecting upon what that contents is.

It took philosophy centuries to approach a definition of the basic categories of existence, of an encompassing notion of reality, to culminate in the 20th century in search of what a reality made of symbols, especially of linguistic ones, is all about. The difference between then and now is that neither Jakobson, nor de Saussure, nor Blanchot, nor Derridá were producing the subject of their inquiries, they were poking something that already existed.

More than patience what is needed, and it’s happening here, as Bob says, is to cover those central questions from as many different angles as they warrant. It is refreshing, and intellectually satisfactory, to know that those who are involved in the designing of the software that will allow for reading environments that are a product of their ontological deliberations, are doing it publicly, and listening carefully to what is being said. They themselves are practitioners, in the somewhat rudimentary form of the blog, of the author/reader interoperability they are aiming at.

So the only sloshing in the tub is the destiny of behaviors of reading. The ink on paper community is still irritated that the digital advocates keep expounding on new reading behaviors at the same time that they migrate the old ones forward to the screen. Face it, digital expression would have been difficult to establish without traditional text reading. Cinema, TV and audio recording had the other territories.

Yesterday I neglected to offer the citation for David Levy. It is Scrolling Forward, Making Sense of Documents in the Digital Age, 2001. This book is a real homesteader’s guide to the territories we are wandering through here at FotB.org.

great post, but I love most your title… great nod to Carver… A title I have felt compelled to echo several times.

Gary, I’ve read & like the David Levy book – mentioned it in the post on finishing things, actually. I think it starts out very strong (with his examination of the various forms of Leaves of Grass) and kinda trickles out when he moves more firmly into the digital. I can see the utility of “document” as a word, but terminology raises its ugly head: does anyone care about the future of documents (besides Xerox maybe)? Just about everyone’s invested in the future of books, in some way or another.

I have a sense that digital expression and its infrastructure of connectivity and behaviors of interplay on the network are headed to a future well beyond books. This sense encourages me to look to the future of the print book without concern for screen based book equivalents. I imagine the print book to have surprising vitality to create its own future especially in attributes of legibility, haptic assimilation and persistence.

I don’t think that Google or Wikis or the collaborative on-line resources are actually adding momentum toward screen based books. If so they are achieving an opposite result as they dissolve and parse books, as they supplant library classification and as they undermine library based services. More likely such results indicate that these bibliographical utilities are more interested in assuming the role of libraries within society, but then maneuvering digital library connectivity as a commercial sector and as a proprietary culture keeper.

Our Friday book studies seminar will review the David Levy book tomorrow. I usually pick up some new ideas there.

The Friday seminar was exciting. I don’t go to them all. Its a weekly forum for students in the Center for the Book here at the University of Iowa.

There were magnificent examples of found “documents” including the double Babblefish transactions (compound automated translation). One student simply emptied the waste basket of receipts at an ATM. It was fascinating to perceive the stories attending balances and withdrawals by evidence of the discarding configuation; crumpled, crushed, folded or floated.

Anyway, we considered the B (book) word and the D (document) word. I wonder if the B word (book) will actually prove an albatross in projections on directions in on-line expression. Future of the book as it relates to genres of digital publication (screen presented) already feels slightly conflicted and restricted. It revealing that we do not have a vernacular beyond synthetics such as blog or Wiki or live journal or listserv.