Since the release of the Sony Reader, I’ve been thinking a lot about the difference between digital text and digital music, and why an ebook device is not, as much as publishers would like it to be, an iPod. This is not an argument over the complexity of literature versus the complexity of music, rather it is a question of interfaces. It seems to me that reading interfaces are much more complicated than listening ones.

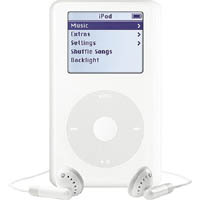

The iPod is, as skeptics initially complained, little more than a hard drive with earphones. But this is precisely its genius: the simplicity of its interface, the sleekness of its form, the radical smallness of its immense storage capacity. All these allow us to spend less time sorting through our music — lugging around stacks of albums, ejecting and inserting tapes or discs — and more time listening to it.

The iPod is, as skeptics initially complained, little more than a hard drive with earphones. But this is precisely its genius: the simplicity of its interface, the sleekness of its form, the radical smallness of its immense storage capacity. All these allow us to spend less time sorting through our music — lugging around stacks of albums, ejecting and inserting tapes or discs — and more time listening to it.

A sequence of smooth thumb gestures leads to the desired track. Once the track has commenced, the device is tucked away into a pocket or knapsack, and the music takes over. That’s the simplicity of the iPod. Reading devices, on the other hand — whether paperback, web page or specialized ebook hardware — are felt and perceived throughout the reading experience. The text, the visual design, and the reader’s movement through them are all in constant interaction. So the device necessarily must be more complex.

In other words, a book — even a digital one — is something you have to “handle” in order to process its contents. The question Sony should be asking is what handling a book should mean in a digital, networked context? Obviously, it’s something very different than in print.

Another thing about portable music players from Walkmen to iPods is that music, in its infinite variety, can be delivered to the senses through a uniform channel: from the player, through the wire, to the ear. Again, with books it’s not so simple. Different books have different looks, and with good reason: they are visual media. This is something we tend to forget because we so strongly associate books with intangible things like stories and abstract ideas. But writing is a manipulation of visual symbols, and reading is something we do with our eyes. So well-considered visual design, of both documents and devices, is crucial — as much for electronic documents as for print ones.

Publishers want their ipod, a simple gadget locked into a content channel (like iTunes), but they’re going to have to do a lot better than the Sony Reader. To date, the web has done a much better job at fostering a wide variety of reading forms, primitive as they may still be, than any specialized ebook device or ebook format. A hard drive with ear phones may work for music, but a hard drive (and a pitifully small one at that) with an e-ink screen won’t be sufficient for books.

if:book

A Project of the Institute for the Future of the Book

Another way of looking at this is that the book isn’t broken. Frankly, music players prior to the MP3 revolution were. The iPod can be seen as a highly successful fix to a bad situation — bad because of old, cumbersome physical media that the industry continued to push for too long. To put it bluntly, CDs (and cassettes before them) suck, in comparison with the all-digital version. But books… well, they don’t suck; they’re not broken. As a result, nobody’s particularly clamouring for the fix.

“Another way of looking at this is that the book isn’t broken. Frankly, music players prior to the MP3 revolution were. The iPod can be seen as a highly successful fix to a bad situation — bad because of old, cumbersome physical media that the industry continued to push for too long. To put it bluntly, CDs (and cassettes before them) suck, in comparison with the all-digital version. But books… well, they don’t suck; they’re not broken. As a result, nobody’s particularly clamouring for the fix.”‘

I beg to differ. Books suck much worse than the CD did. First, they’re significantly bigger than the CD (which itself was pretty bulky). Try to take 100 books with you to a class sometime — or try to store 10,000 of them in a small house.

More importantly, they’re not easily searchable, and most book indexes are worthless (a problem which, for some bizarre reason, Sony doesn’t try to solve since the texts on the e-reader aren’t searchable). Try to find a non-indexed phrase that you remember from a 500 page book some time.

Finally, they have (relatively) high printing and distribution costs which would be lowered if there were a single standard to distribute them electronically (much as the written word has flourisehd online thanks to the openness of http).

The book may be broken, but its primary casual interaction (browsing and reading) doesn’t cause the pain that the CD player and tape deck did.

I agree that searchability and volume are pains that need to be fixed, but they’re somewhat less obvious, to the casual reader, than the deficiencies of music players before the iPod. It’s not too terribly surprising, then, that none of the ebook solutions we see address the real problems of paper books.

More to the point, it’s very easy for me, as a bystander, to see someone using an iPod, and flash on an understanding: wow, I could stop toting the pack of CDs and discman in my backpack! On the other hand, when I see someone reading an ebook, it doesn’t immediately communicate the benefit of the device. It just looks like an expensive toy.

The immediate and obvious benefit of a device is what makes it desirable to others, so in what environment would an ebook produce that epiphany? I’m thinking that, probably, an academic setting might be exactly that. When one grad student sees that his companion is working on her doctorate, and has replaced a satchelful of books with a slim device, and that her doctoral thesis is cross-referenced with the electronic and networked books in it, and that you can look up other references in the library via the wifi, then maybe you’ve got the same effect that the iPod had.

Which only makes the Sony device look worse, because it can’t do *any* of that.

Part of the pleasure of reading is that it’s tactile. I was devastated when my bag was stolen with my pocket Nietzsche in, because I’d scribbled all over it. It contained two or three years’ worth of my responses to the writing. It felt personal, and was irreplaceable. I find it hard to imagine being able, in an ebook, to replicate the pleasure of revisiting a familiar text with fresh eyes, and a pencil in one hand.

These physical characteristics of books structure knowledge in a particular way: they tend to linear thinking, in-depth analysis, centralisation and canonisation of knowledge. In many ways, the Net tends in the opposite direction. My Nietzsche was set in stone – the writer is long dead, his thoughts much-debated. The form, and dramatic conventions of print publishing, deify the ‘exact words’ and the individual who produced them. In contrast, when I meet text through a digital interface I relate to it very differently: it’s more disposable, more manipulable, less straightforwardly copyrightable.

I think ebooks would spell the end of the Author as cultural category in the way (even now, after Barthes claimed ‘the death of the author’ way back in the Sixties) it’s understood now: the vatic writer channelling wisdom for the grateful, self-improving hoi polloi. When everyone can publish, and everyone can replicate, writing takes on a very different meaning.

We already see that in fanfic and slash writing, blogs and fora and so on. But becoming ‘a novelist’ is still , for many, considered the apogee of achievement for ‘aspiring writers’. And much more of that status is bound up in the physical form and mode of production of books than is immediately obvious.

Ebooks would, I believe, spell the end of (or total transformation of) canonisation both of the novel as we know it, and also of those who write them. Anyone developing ebook technology in order to reproduce the ‘novel’ format would do well to consider how the technology undermines many of the conditions that help to shape the content they wish to disseminate.

Of course the Sony machine is imperfect, but when a device emerges that you can load all your books onto, is easy to read, has amazing battery life, you can search text, write stick-notes on, enjoy a video picture instead of a colour print, as well as access new reading material via the internet etc at a reasonable price, then the traditional book is dead.

It is only a matter of time. It will be marketed like raisor blades and printers… cheap to buy, but paid for in the costs of buying your latest book or magazine – electronic distribution is so cheap so most of the profits won’t be wasted on printing, paper and delivery.

It is a surely pot of gold awaiting the rainbow.

Books suck? You’re kidding, right?

They’re portable, cheap, mostly indestructible (fire is the only real threat — even water doesn’t really kill them) and the user interface doubles as not just the storage device, but also performs valuable marketing functions, acts as a social signpost, and looks beautiful when displayed in the thousands along the walls of a small house.

This other thing you’re talking about, which is digital and searchable and nearly zero-cost, already exists. It’s called the web, and it’s great. But its relationship to books is far more complex, and more interesting than a simple replacement of one technology with another.

I agree with the earlier poster about writing in the marigins – it’s a useful feature that hasn’t been effectively duplicated by the e-book, at least not yet.

I took a course in law school last year where the professor used a text that he authored. In the back of the book was a CD with a complete copy of the book in pdf format. He wasn’t worried about piracy problems, I guess. Great, I thought – no more lugging the book to class, and I can read this thing whenever I want right from my laptop. Well, it wasn’t long before I missed the ability to underline and write notes in the margins, which you can’t do with a pdf. The book was also nice for the exam, which was open book (meaning a real book – not open laptop).

Although the electronic version was nice when it came to looking things up via the word search in Adobe Acrobat, without some way to make notes in the margins and highlight or underline text, I didn’t see an electronic format as beneficial on its own and wound up using the real book more often than not.

“I think ebooks would spell the end of the Author as cultural category in the way”

People aren’t completely stupid. Even when everyone has the ability to publish their work, readers will still distinguish good from bad writing, and authors will accumulate reputations and fans accordingly. POD (print-on-demand) and vanity publishers already enabled anyone to become a “printed novelist” on paper quite some time ago, but how many self-published books have become hits?